On 26 July 1913 – in a year more often associated with Suffragette militancy and the death of Emily Wilding Davison – 50,000 suffragists and supporters of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) converged on Hyde Park for a rally calling for votes for women. This was the culmination of a five-week, nationwide Women’s Suffrage Pilgrimage.

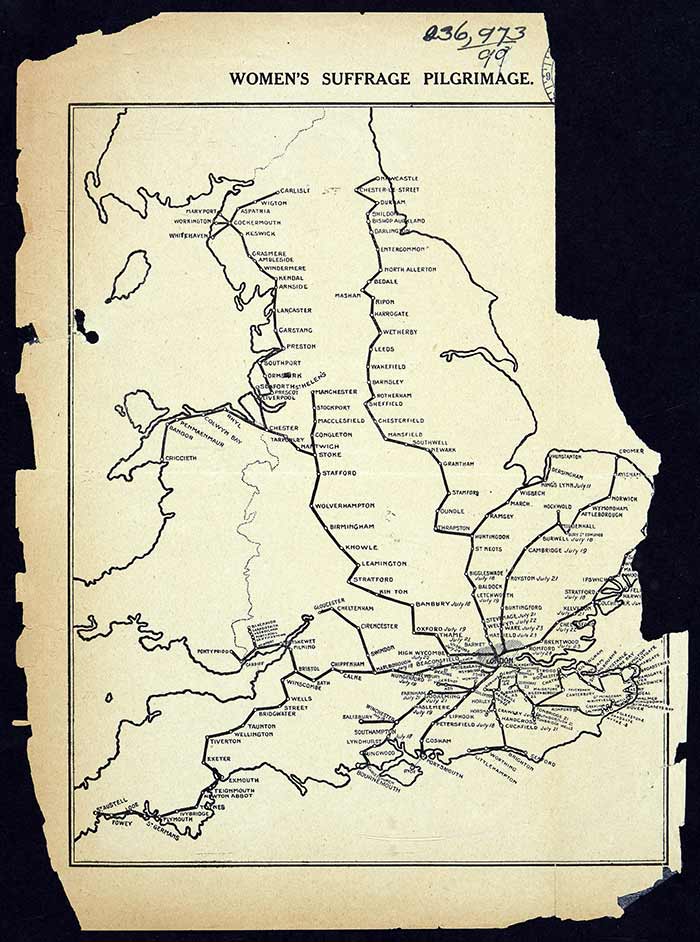

Women’s Suffrage Pilgrimage map from ‘The Common Cause’ which shows the extent of the national suffrage campaigns, June to July 1913. Reference: HO45/10695/231366.

The Pilgrimage was the idea of Katherine Harley, no doubt inspired in part by the Women’s March from Edinburgh to London in October 1912. However, this was to be on an entirely different scale.

The Pilgrimage. What does it mean? It means that there are thousands of law-abiding women who believe that it is only just and right that women as well as men should be allowed to vote … because laws are made which concern women as well as men … It means that the women taking part … wish to bring more clearly home to you the reasons why they desire this reform … It means that they wish to convince you that the great majority of women who are asking for the vote are opposed to violence … The Pilgrimage is above all the outward sign of women suffragists unalterable determination not to cease from pressing their claim to the vote by every lawful means in their power until the vote is won. [ref] Marjory Lees’ Diary, 2OWS/2, LSE Women’s Library. [/ref]

The Pilgrimage began on 18 June with six main marching routes to London, from Carlisle and Newcastle in the north to Lands End and Portsmouth in the south. Some pilgrims, in uniform dress and adorned with red, white and green badges, sashes and ribbons, completed entire routes, while others joined for a few days at a time. Along the way, they held indoor and open-air meetings to promote the cause.

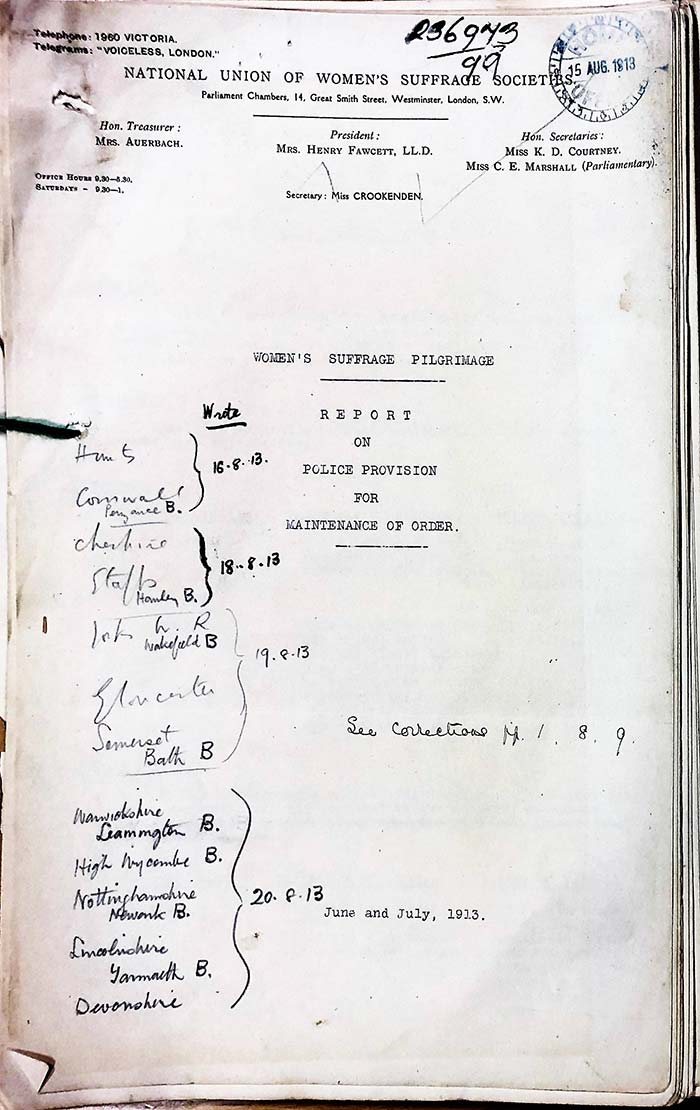

While many were well received by orderly audiences and enjoyed adequate police protection, there were also hostile encounters; in some cases these arose from the public’s tendency not to differentiate between the peaceful suffragists and the militant suffragettes. These incidents were recorded by the NUWSS and submitted in a report to the Home Office.

At Nantwich in Cheshire it was reported that ‘children and young people’ were ‘rowdy, making meeting almost impossible. Afterwards chased Pilgrims to station throwing dirt and stones; one pilgrim hurt with stone on the head. Police took no action.’ [ref] Women’s Suffrage Pilgrimage Report on Police Provision for Maintenance of Order, by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. June and July 1913. HO 45/10701/236973, The National Archives. [/ref]

At Stafford the crowd was reported as being ‘very rough’, with Miss Margaret Ashton being ‘lamed by a kick.’ The Chief Constable of Staffordshire wrote:

I regret that Miss Ashton should have been kicked … One of my men also was badly kicked in rescuing one of these females from the somewhat hostile crowd. A disturbance arose through the action of a sympathiser of the female orators in the crowd in assaulting a boy who I suppose was interrupting although he declared he had done nothing: anyhow this woman committed an illegal assault and the crowd resented it. [ref] Summary of Police reports on representations made to Secretary of State by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, 1913. HO 45/10701/236973, The National Archives. [/ref]

At Stratford-upon-Avon the crowd was described as ‘very unruly.’

Women’s Suffrage Pilgrimage Report on Police Provision for Maintenance of Order, by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. June and July 1913. HO45/10695/231366.

Police quite inadequate in number, but also deliberately abstained from interference and stood by laughing and shrugging their shoulders. One of them was heard to say, “They’re asking for it, let them have it”. [ref] Women’s Suffrage Pilgrimage Report, June and July 1913. HO 45/10701/236973, The National Archives. [/ref]

The Chief Constable for Warwickshire responded: ‘The Police carried out my instructions not to interfere in any way but to give personal protection when it was required.’ [ref] Summary of Police reports, 1913. HO 45/10701/236973, The National Archives. [/ref]

At High Wycombe the NUWSS reported ‘great disorder’, ‘missiles thrown, platform rushed.’ [ref] Women’s Suffrage Pilgrimage Report, June and July 1913. HO 45/10701/236973, The National Archives. [/ref] One pilgrim recounted the story in more detail to The Bucks Herald:

Some of us for the first time found ourselves in the midst of a packed mass of men, howling steadily, and … felt the weight of them as, linked arm in arm, they broke through our procession in spite of the police; and watched the variety of missiles whizzing about our speakers. I myself only met with clods, pebbles, and cherry stones … “Suffragist chasing” was a game the Wycombe youths were loth to drop till a late hour of the night, and even the victims saw some of the humour of it. Two of us were rescued out of an ugly rush by the inhabitants of a corner house, and thence got away by ladders over a high garden wall; others sat in the darkened premises of the garage listening to the mob battering on the doors and smashing the windows, and concerting plans for escape by telephone. [ref]The Bucks Herald, 2 August 1913, p 3 [/ref]

In instances such as these there was a tendency for Chief Constables to downplay reports of mob violence as ‘horseplay’, offering contradictory accounts of the incidents and suggesting that the more extreme reports were exaggerations.

However, in some cases police numbers were clearly not up to the task. At St Neots in Huntingdonshire the meeting was described as ‘very disorderly’ by the NUWSS.

Missiles thrown, platform rushed, pilgrims knocked down and trampled upon. Inspector said he could not offer any protection unless meeting were abandoned … it was only when one of the organisers told him that unless he protected the pilgrims questions would be asked about him in Parliament that he took any steps to ensure their safety. [ref] Women’s Suffrage Pilgrimage Report, June and July 1913. HO 45/10701/236973, The National Archives. [/ref]

The police response was recorded as:

The meeting had been well advertised in the surrounding districts and a crowd of several thousands gathered in the Market Square. The local Inspector says that he had 2 or 4 days’ notice of the meeting, but had no reason to anticipate disorder as all previous meetings of Suffragettes [sic] had been orderly. He arranged for all the Police in his Division (10 in number) to be on duty in the Market Square, and took all possible steps to protect the pilgrims and maintain order.

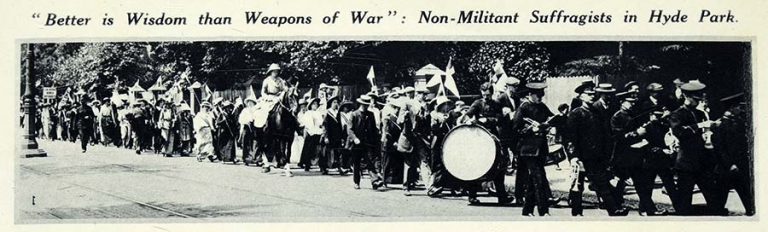

‘A pilgrimage of law-abiding suffragists: marching through Ealing.’ Image from the Illustrated London News, August 2 1913. ZPER 34/143.

The crowd was noisy but good-humoured, and there was a great deal of pushing and horseplay. The Police surrounded the speakers and tried to keep off the crowd but found it impossible to protect the pilgrims and look after the women and children in the crowd who were in danger of being trampled upon. The Inspector was accordingly compelled to inform the speakers that he could not be responsible for their safety unless they abandoned the meeting. Eventually they all accepted his advice and were escorted to safety.

The difficulties of the police were greatly increased by the fact that the pilgrims insisted on addressing the crowd from three different places at the same time although the Police tried to persuade them to keep together. None of the pilgrims were knocked down and trampled on or hurt in any way, and the Police saw only one missile thrown. [ref] Summary of Police reports, 1913. HO 45/10701/236973, The National Archives. [/ref]

Annie Ramsay evocatively recalled her experience of being a pilgrim in such circumstances.

I can assure you there is nothing that seems so terrible as that swaying mass of humanity one is so helpless to resist. Then comes the horrible thoughts “the children” and you shout “please keep back” there are children here. You breathe again and force your way a little out and then comes another “sway” and you give up the ghost – the policemen take action – you get behind him and breathe a long breath. It seems a mighty long time since you breathed properly. You ask yourself – “is it worthwhile – to undergo all this degradation. Men they say are the more reasonable creatures than women and this is how they prove it – heavens”.’ [ref] Annie Ramsay’s papers, 7ARA, Box FL086, LSE Women’s Library, p. 30-31. [/ref]

On 24 July, Catherine Marshall, parliamentary secretary to the NUWSS, wrote to Reginald McKenna, the Home Secretary, asking if he would receive a deputation of pilgrims who had suffered violence.

Owing to some defect in the law or in its administration, there does not seem to be any means of redress open to women … A woman, like Miss Margaret Ashton of the Manchester City Council, can be stoned in the public streets with impunity, whereas had she been a plate glass window the offender would have been severely punished. [ref] Letter from Catherine Marshall to Reginald McKenna, 24 July 1913, HO 45/10701/236973/77, The National Archives. [/ref]

McKenna agreed to write to each county and borough, requesting that their chief constables investigate the matter. A report, summarising their responses, concluded: ‘The Police seem everywhere to have done their best for the pilgrims and many of the complaints made are distinctly ungenerous, and some are practically contradicted by letters and statements to the Police taken at the time.’ [ref] Summary of Police reports, 1913. HO 45/10701/236973, The National Archives. [/ref]

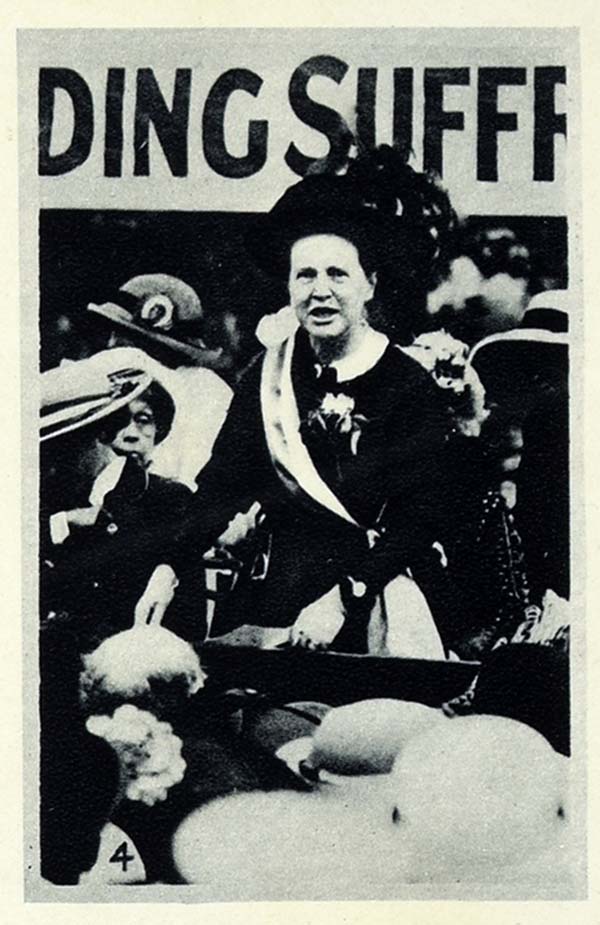

The procession enters Hyde Park and Millicent Fawcett addresses the great meeting. Illustrated London News, August 2 1913. ZPER 34/143.

The Pilgrimage culminated in a service at St Paul’s Cathedral and a rally of 50,000 people at Hyde Park on 26 July. Speakers addressed the crowd from 19 different platforms. Millicent Fawcett later recalled, ‘It was all like a wonderful dream.’ [ref] Millicent Fawcett’s autobiography: What I Remember (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1924), 210. [/ref]

The pilgrimage succeeded in persuading Asquith to receive his first women’s suffrage deputation since November 1911. However, no change in government policy followed, much to Millicent Fawcett’s disappointment.

We came to you with fresh evidence of the demand for Women’s Suffrage in the Country; with fresh evidence, if that were needed, of the earnestness and determination of the supporters of our cause … In reply you all assured us that in your opinion Women’s Suffrage is unpopular in the Country; that you were prepared “on suitable occasions” to mention it in your speeches … and that you could say nothing further … In the meantime you advised us to “rehabilitate” the movement in the country and render it “popular”. [ref]

Millicent Garrett Fawcett archive, 7MGF/A/1/083, LSE Women’s Library. [/ref]

While Asquith may not have been swayed by the pilgrimage, it nevertheless proved a moral victory for the suffragists and helped win many more hearts and minds both within and outside Parliament.

The Citizens project is led by Royal Holloway, University of London, and charts the history of liberty, protest and reform from Magna Carta to the Suffragettes and beyond.

Dr Matthew Smith is Citizens Project Director and Katie Carpenter is a Citizens project intern.

Very good blog. Although a mere glimpse into the struggles experienced by peaceful Suffragettes in 1913, it’s a reminder that in 2018 not much has changed. The right to vote & other laws passesd to level the playing field are still fragile. Thank you to the Author for a timely reminder of the precious gift our ancestors fought so hard to implement; and that we must ensue that it is protected so that it stands for generations to come.