This story follows a series of blogs from the curators of Treason: People, Power & Plot exploring how the 1352 definition of high treason, as ‘compassing or imagining’ the death of the king, his queen, or their eldest son, has been interpreted over the last 700 years. This third blog examines the attempts of William Pitt’s (1759–1806) government to expand the definition of treason to meet the threat of peaceful parliamentary reform campaigns.

On 5 November 1794, Gunpowder Day, Thomas Hardy’s trial for treason reached its conclusion. It had lasted nine days, unprecedented for the time. The jury’s foreman reportedly collapsed, after delivering the verdict: not guilty. Hardy emerged from the court to public jubilation. Over the coming days, 11 other men were similarly acquitted or had their charges dropped. They had evaded a treason conviction and struck a blow against the government.

Liberty, equality, fraternity

Codified in 1352, the Treason Act had proved itself flexible in its application, able in the hands of a strong government to render an ever-expanding definition of actions treasonous. But the world in 1794 was very different. King George III’s power was mostly exercised by his ministers, who drew their authority from Parliament. But in the late 18th century, Parliament was hideously undemocratic. Less than 5% of the adult population could vote for its members, most of these from the upper-middle and upper classes. The ideals of the French Revolution of 1789 – liberty, equality, fraternity, equal political rights – were in direct conflict with the British constitutional settlement.

These ideals had crossed the Channel. ‘Radicals’, brandishing copies of Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man (1792) and other pamphlets began to demand, albeit peacefully, that the parliament and constitution be reformed. Ministers saw it as an existential threat, but it was one directed at Parliament, and peacefully. Could they really be said to be ‘compassing and imagining’ the King’s death?

Thomas Hardy, the LCS, and demanding reform

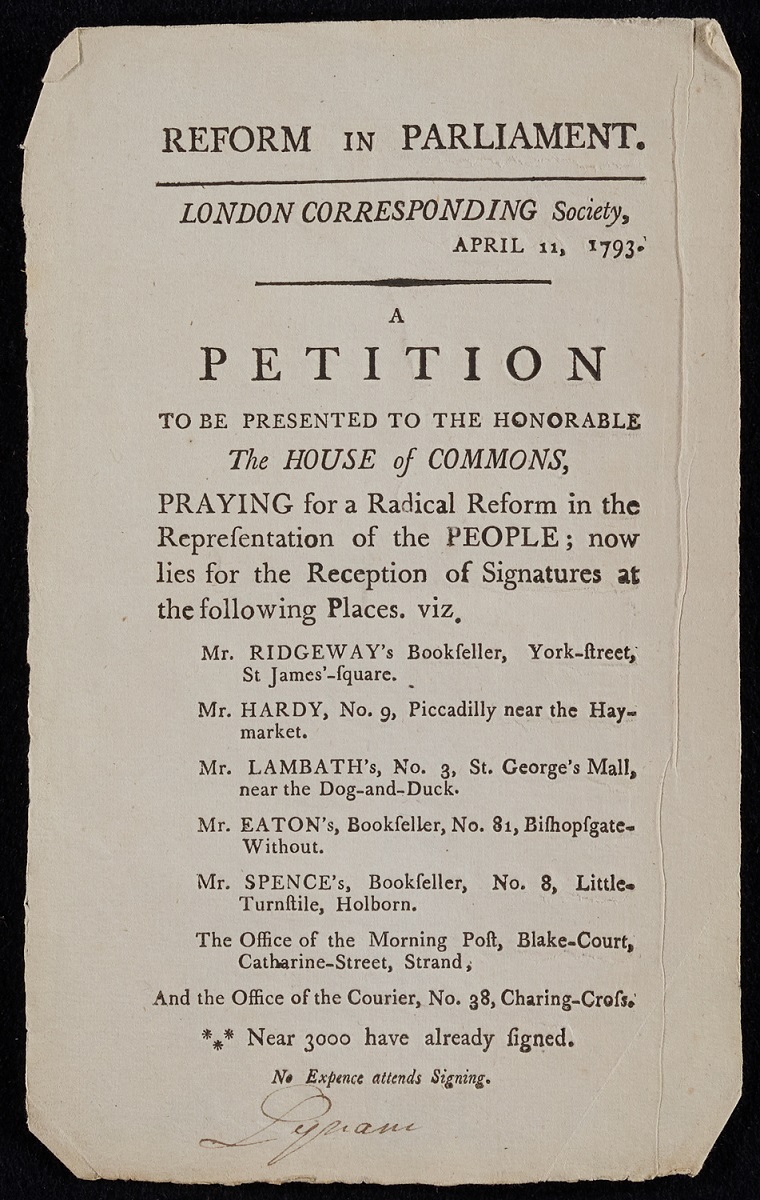

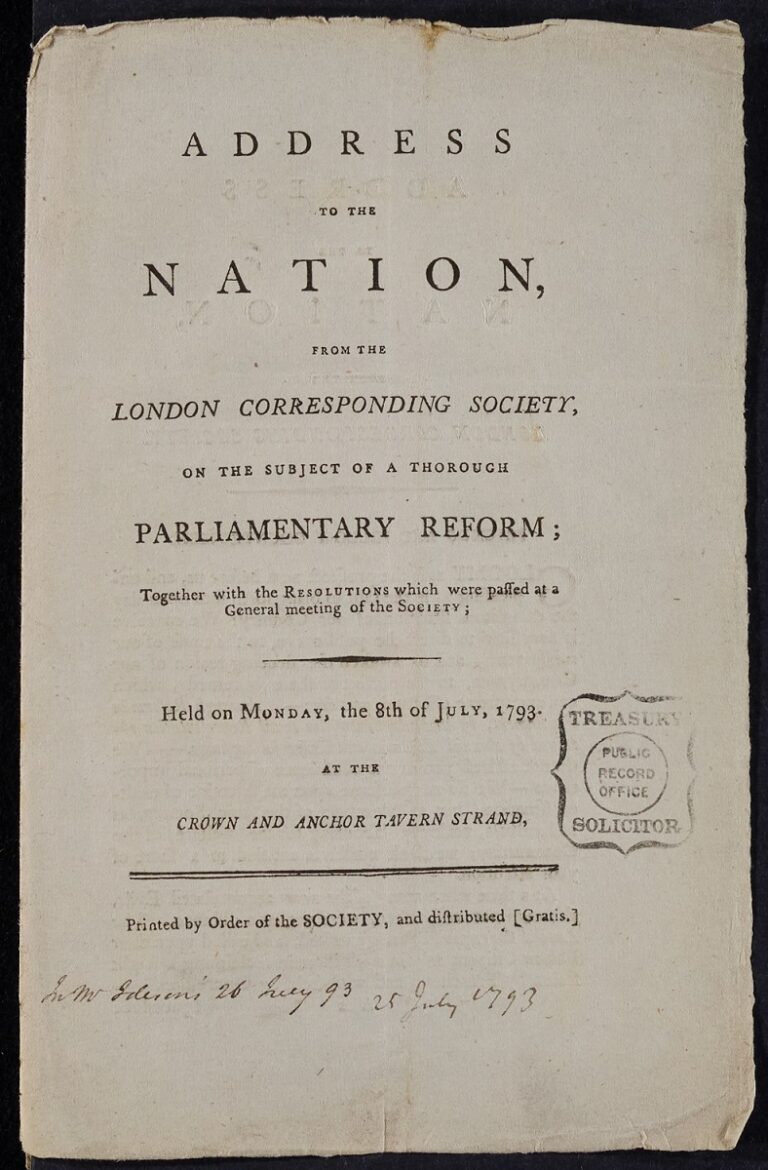

Thomas Hardy was one of these radicals. A shoemaker, in January 1792 he founded the London Corresponding Society (LCS), a working-class organisation demanding universal male suffrage and constitutional reform. By April 1792, the LCS had around 650 members. They published an ‘Address’, a public statement of their ideology and objectives. Liberty was a man’s birth-right, they said, without a vote he was not free. To the LCS, the unreformed parliament was the cause of the corruption, high taxes and oppressive restrictions on political expression in Britain. Universal (male) suffrage was offered as a cure. But they were also careful to insist they were peaceful, expressing an ‘Abhorrence of Tumult and Violence’ (see footnote 1).

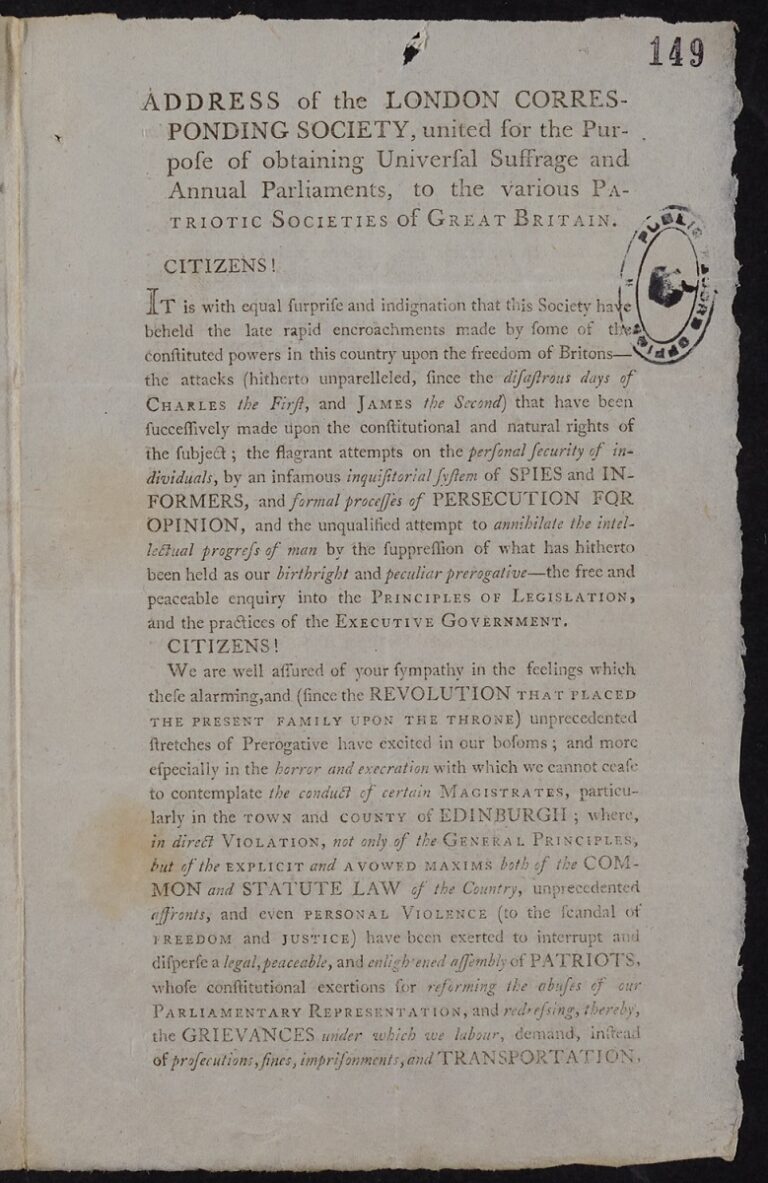

The LCS were part of a network of corresponding societies and reform associations, all anxiously watched by government spies. In November 1793, the LCS sent two delegates to a radicals’ convention in Edinburgh. They were arrested for sedition and transported for life. The LCS were outraged, issuing an Address in January 1794 condemning, ‘an inquisitorial system of SPIES and INFORMERS, and formal processes of PERSECUTUON FOR OPINION’. Hardy began writing to other societies, intent on holding another convention, this time in England (see footnote 2).

Hardy’s arrest

But soon it was Hardy who was arrested. On 12 May, his house and shop were raided, and his papers taken. Other radicals were arrested in the following days. Parliament convened a ‘committee of secrecy’ to work out if the corresponding societies were part of a treasonous conspiracy. They published their report in just four days. As far as they were concerned, Hardy’s proposed convention was intended to, possibly by force of arms, ‘supersede’ Parliament as the representative body of the people – ‘a Traitorous Conspiracy for the Subversion of the established Laws and Constitution’ (see footnote 3).

Hardy was indicted for high treason – compassing and imagining the King’s death and attempting to ‘excite’ rebellion and war against him. This might seem strange: all he had done was call meetings and publish pamphlets. But as James Eyre, Lord Chief Justice, explained at the preliminary hearing for Hardy’s trial, ‘Compassing’ the King’s death did not necessitate a design to kill him. The Crown was the ‘common centre’ of the realm, and ‘all traitorous attempts upon any part of it are instantly communicated to that centre’. The convention would have ‘usurped’ Parliament, possibly by force, Eyre said. Such a course inevitably led to the monarch’s death and was therefore treason (see footnote 4).

Thomas Erskine’s defence

Hardy and his co-defendants were blessed with a good lawyer, the famed Thomas Erskine. The prosecution’s case was one of voluminous evidence, much of it innocuous and disconnected, but contorted by the government into the shape of a revolutionary conspiracy. Erskine’s defence was lauded. He described the case against Hardy as ‘tyrannical laws, more tyrannically executed… speculations concerning consequences, when the law commands us to look only to intentions’. No proof had been offered of any, ‘wicked contemplation to destroy the natural life and person of the King’. It worked; Hardy was acquitted (see footnote 5).

Treason has always been a public spectacle. The trial was a chance for the state to condemn the ideas and body of the accused, and formally brand them a traitor. The inevitable execution a chance to desecrate their body and soul before the crowd. So, for the state to lose one, was embarrassing, and worrying.

But the government’s case had been weak – ‘compassing and imagining’ had always been flexed when treason was needed, but in Hardy’s case it was a step too far – too removed from George III and too fanciful in suggesting, with almost no evidence, that he meant to overwhelm Parliament by holding a glorified meeting.

The ‘new-fangled treasons’

When Parliament sat again after hardy’s trial, in December 1794, opposition MPs mocked the government’s failed case. They demanded an inquiry into the ‘new-fangled treasons, introduced by Ministry, in direct and unconstitutional contraction to the statute of Edward the Third’. But the government made an astonishing response. Prime Minister William Pitt told the Commons that while Hardy had not been guilty of ‘formal or technical treason’, he bore a ‘moral guilt … as destructive to the State as any treason’. He promised new laws to ensure that such a mistake was not made again (see footnote 6).

The Treason Act 1795 was an attempt to reimagine treason for the modern era as a primarily political crime aimed at the state, not just the Crown. It became treasonable not just to compass and imagine the King’s death, but also his deposition (including implicitly by the subversion of Parliament), or ‘any bodily Harm … Imprisonment, [or] Restraint’. The scope of levying war was expanded too, to include actions which sought to intimidate the King, or ‘compel’ him to change his ‘Counsels and Measures’ (ministers and policies). Speeches or writings were explicitly made overt acts. In short, it attempted to codify the very actions that Hardy was acquitted on as high treason. Billed as a temporary measure, it was made permanent in 1817, and was not fully repealed until 1998.

Find out more in our free exhibition Treason: People, Power & Plot, which runs until 6 April 2023. You can also read more in our book, A History of Treason, available to purchase now from our online shop and all good booksellers.

Footnotes

- Catalogue reference: TS 11/951/3495

- Catalogue reference HO 42/28/64

- FIRST REPORT FROM THE Committee of Secrecy, To whom the several PAPERS referred to IN HIS MAJESTY’s MESSAGE OF THE I2TH OF MAY, 1794. And which were presented (sealed up) to the HOUSE, by MR. SECRETARY DUNDAS, Upon the 12th and 13th Days of the said Month, BT HIS MAJESTY’s COMMAND, WERE REFERRED; And. who were directed to examine the Matters thereof, and report the same, as they should appear to them, to the House; have proceeded, in Obedience to the Orders of the House, to the Consideration of the Matters referred to them. Ordered to be printed 17th May 1794, (London:J. Debrett, 1794), pp. 3-40

- Joseph Gurney, The Trial of Thomas Hardy for High Treason, at the Sessions House in the Old Bailey, Vol. I, Martha Gurney, London, 1794, pp. 3-13

- James L High (ed.), Speeches of Lord Erskine, while at the Bar, Volume II, (Chicago: Callaghan and Company, 1876), pp. 403-409

- The Parliamentary register, or, History of the proceedings and debates of the House of Commons, Vol. 40, 30 December 1794 – 27 June, (London: J. Debrett, 1795), pp. 2-12