This blog is published as part of Disability History Month (22 November to 22 December 2019).

Thalidomide was one of the worst man-made medical disasters in history and had far-reaching medical and social consequences. Manufactured by the German company Chemie-Grünenthal and licensed for sale in 79 countries under 49 different brand names, the drug thalidomide gave rise to the birth of more than 10,000 babies born worldwide with deformities in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The wide-ranging impairments included limb damage, absence of limbs, and damage to the nervous system and internal organs.

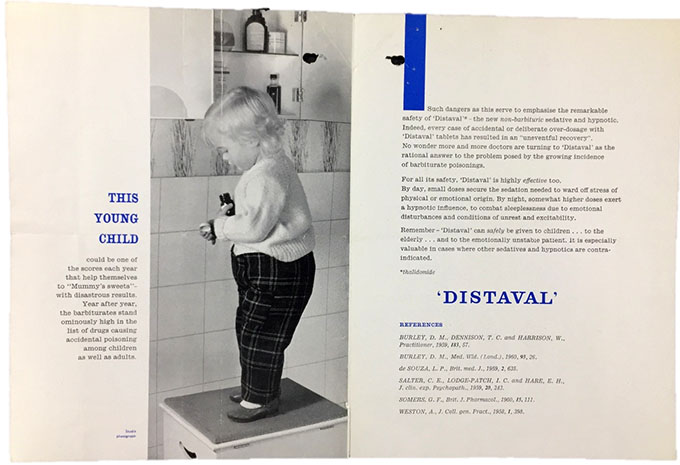

Disturbingly marketed as ‘free from untoward side-effects’, thalidomide was licensed for sale by Distillers (Biochemicals) Ltd in the UK and was sold under the names Distaval, Asmaval, Tensival, Valgis and Valgraine. It was prescribed by NHS and private doctors between April 1958 and November 1961, during which time it was used primarily as a sedative and given to pregnant woman to relieve the symptoms of morning sickness.

Leaflet for Distaval (thalidomide) promoting its ‘safety’. The Distillers Company, 1960. Catalogue ref: MH 135/109

Records relating to thalidomide at The National Archives

The National Archives, as the official archive for the UK Government, holds correspondence, memorandums, reports, and committee minutes relating to the aftermath of thalidomide, particularly in records deposited by the Ministry of Health and, after 1968, the Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS). Much of the correspondence calls on the Government to take action, either by offering compensation to the survivors, increasing regulation of the drugs industry, or to issue a public inquiry; other records can be found within series that cover social services, education, and research and development.

Pressures to regulate the pharmaceutical market led to the creation of the Committee on the Safety of Drugs in 1963, an independent advisory board chaired by Sir Derrick Dunlop. Yet despite public outcry, the Government rejected calls to carry out a public inquiry and it was not until 2010 that the Health Minister, Mike O’Brien, gave an official apology in Parliament.

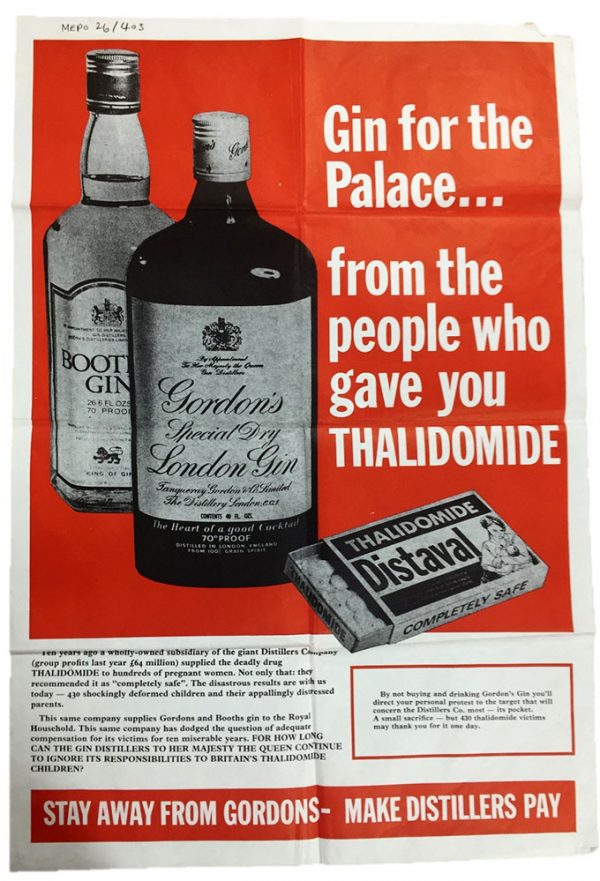

The battle for compensation

It is estimated that 40% of children affected did not survive past their first birthday. The true number will never be known, with many victims going unrecorded as a result of miscarriages, stillbirths and, as anecdotal evidence has highlighted, infanticide[ref]H Evans, ‘Foreward’ in M Johnson, R G Stokes, T Arndt, The Thalidomide Catastrophe: How it happened, who was responsible and why the search for justice continues after more than six decades (Exeter, 2018), p. 9.[/ref]. Moreover, many women at the time did not realise initially they had taken thalidomide, having been prescribed it under one of its many brand names, and later on, recorded numbers only pointed to those who were deemed eligible for compensation[ref]Thalidomide ‘Y List’ inquiry, BN 90/1-4.[/ref]. The battle for compensation was long and complex and included an organised campaign to boycott the Distillers Company products. The documentary Attacking the Devil: Harold Evans and the Last Nazi War Crime, currently showing on Netflix, charts the journalistic campaign undertaken at The Times in the 1960s and early 70s that fought for compensation for the survivors.

Poster from the ‘Make the Distillers Company Pay’ campaign encouraging a boycott of the Distillers Company. c.1971-1972. Catalogue ref: MEPO 26/403

Government services: Limb-fitting

The provision of services was likewise full of complexities. Early on when the public was calling on the Government to provide help the official Ministry line was that ‘there has always been an appreciable number of cases of congenital deformity, so that this condition is no new thing under the National Health Service for its treatment. There are no grounds for thinking that the service cannot deal with the recent increase in such cases’[ref]Stock reply to a number of a letters found in MH 135/109.[/ref].

Of course, the reality was different for those working on the front line. The Medical Administrator at Chailey Heritage, a charity that provided education and care for disabled children, pronounced their fears in The Lancet that ‘this is little short of a major social disaster which demands special priority plans to meet it’, and called for the urgent need for coordinated services. Moreover, drawing attention to the children’s educational needs, they stated that despite the fact that ‘many of the infants are seemingly of normal intelligence…they will be at a great disadvantage with the amount of prosthetic ‘clutter’[ref]‘Letters to the Editor: Thalidomide damaged babies’, The Lancet, 30 June 1962. Newspaper cutting in MH 151/64.[/ref].

Philippa was the first baby to be fitted with powered arms, The Guardian, 29 January 1963. Catalogue ref: ED 50/932

The rise in congenital disabilities as a result of thalidomide prompted increased research and development into prosthetic limbs including those powered by gas as well as neuromuscular electrical tension. Philippa, at 11 months old, was the first baby to be fitted with gas-powered arms in 1963[ref]‘New Limbs by gas’, The Guardian 29 January 1963. Newspaper cutting in ED 50/932.[/ref]. Records of the Medical Research Council give insight into the pioneering research being undertaken by the likes of Dr A B Kinnier-Wilson at the Biomechanical Research and Development Unit (BRADU) at Roehampton among others.

However, there was considerable disparity between research triumphs and the day-to-day life of survivors and their families. After a meeting between the Society for the Aid of Thalidomide and representatives from the DHSS in 1969, it was stressed that ‘important things that we hoped to show you, like the limbs actually being fitted on the children and how clumsy, ill-fitting and inadequate they were, causing actual physical harm as well as frustration to the children, were not done, simply because there was not enough time’[ref]Letter from the Secretary to the Society for the Aid of Thalidomide Children, to David Ennals, Minister of State for the DHSS, 19 February 1969, MH 168/89.[/ref].

Letters to the Government received from parents reveal the daily frustrations encountered when using the limb-fitting service. The main complaints related to the control of powered arms, the excessive weight of the limbs, damage to clothing, and the distance and cost that the child had to travel to get fitted. One parent protested that ‘My husband earns good money, compared to some, yet we cannot afford these things and very often have to borrow money when we go to Roehampton. I’m not only thinking of us, when I state our case, but many others, who maybe do not earn a good wage’[ref]Letter from a parent to the Minister of Education, 23 October 1962, ED 50/932.[/ref].

Manufacturing delays were also highlighted: for one child, over the course of four years, the total manufacturing wait time totalled 2.3 years for 10 different limbs[ref]Redacted letter from a parent to the Secretary of the Society for the Aid of Thalidomide Children, 4 June 1968, MH 168/89.[/ref]. In another case, the mother of a daughter who was born with no legs but with feet stated that ‘although some type of limb was supplied from the age of two years it was never possible to obtain new appliances in less than 3 ½ months, and on two occasions the child has had to wait 5 ½ months. Limb fitters were unwilling to carry out simple adjustments to appliances to improve comfort, and weight seemed out of proportion to child’s body weight’[ref]Redacted case from a parent to the Secretary of the Society for the Aid of Thalidomide Children, MH 168/89.[/ref].

Louise, a thalidomider[ref]A term used by survivors of thalidomide.[/ref], reflected in her memoir that ‘We all became quite professional at using them but none of us liked wearing them and not just because of the weight…the arms would dig into me, every time I moved my hand I heard “hss, hss”, from the gas and water power system and they were forever going wrong. I felt more disabled in them than I did without them’[ref]Louise Medus, No Hand To Hold & No Legs to Dance on: Laughing and Loving – A Thalidomide Survivor’s Story (Kindle edition, 2009), p. 581.[/ref].

What do these records show?

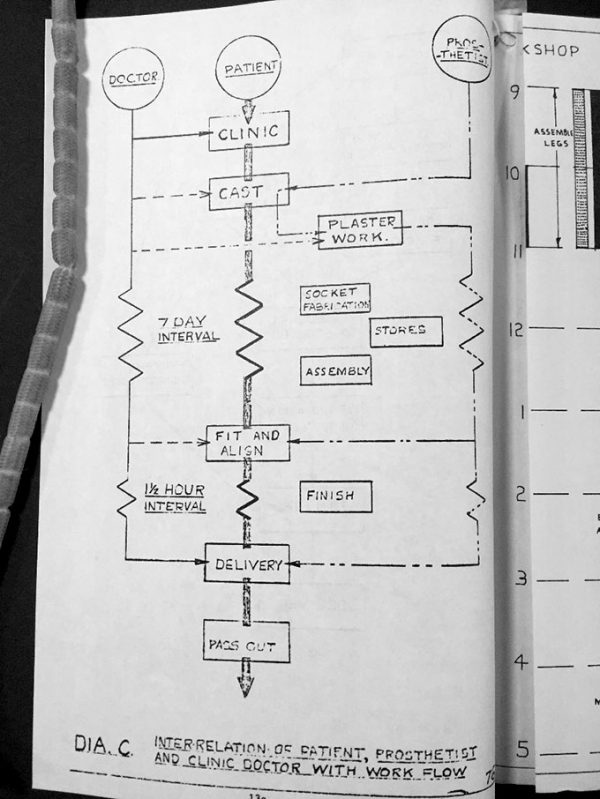

Records held at The National Archives point to the processes behind the limb-fitting service and highlight the extensive network of doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, social workers, engineers and technicians involved in providing services, as well as the varying groups who influenced the research and development of prosthetics, namely thalidomide survivors, parents, the State, engineers, commercial bodies, and medical practitioners.

Chart showing the workflow of the limb-fitting service, BRADU Bulletin, 1971. Catalogue ref: PIN 59/332

The main set of records relating to the limb-fitting services can be found within the Records of the Supply Division of the Ministry of Health.

I’ve just bought one of those posters!! I never knew they existed. It’s tatty but my goodness what a find! My own mother was offered that drug in 1959… thank heavens she turned it down .