To help celebrate National Volunteers’ Week, this is the latest in a series of blogs to promote the work of volunteers at The National Archives cataloguing the series of records WO 416. This series consists of record cards of over 200,000 British and Allied prisoners of war and civilian internees captured in German-occupied territory during the Second World War.

The project expects to complete in Spring 2023. Other fascinating stories identified by volunteers since the project started in 2017 can be found here. Katrina is one of 22 volunteers working on the project and we are grateful for all of their efforts.

Any soldier, airman or sailor captured by the Germans during the Second World War may have felt his war was over. After all, prisoners of war (PoWs) were protected by the Geneva Convention. They were wrong. While standards in the PoW camps never sank to the horrors of the concentration camps, they often failed to meet the standards set out in the Convention. In reality, PoWs were embarking on another battle – the battle to survive.

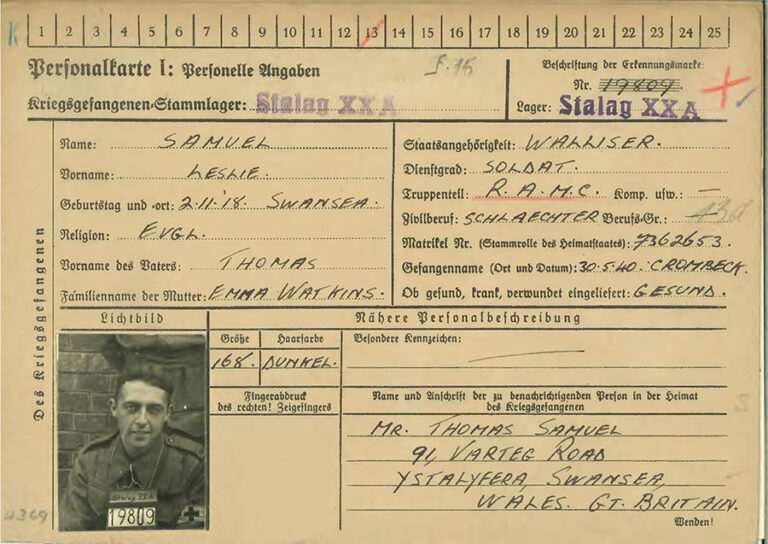

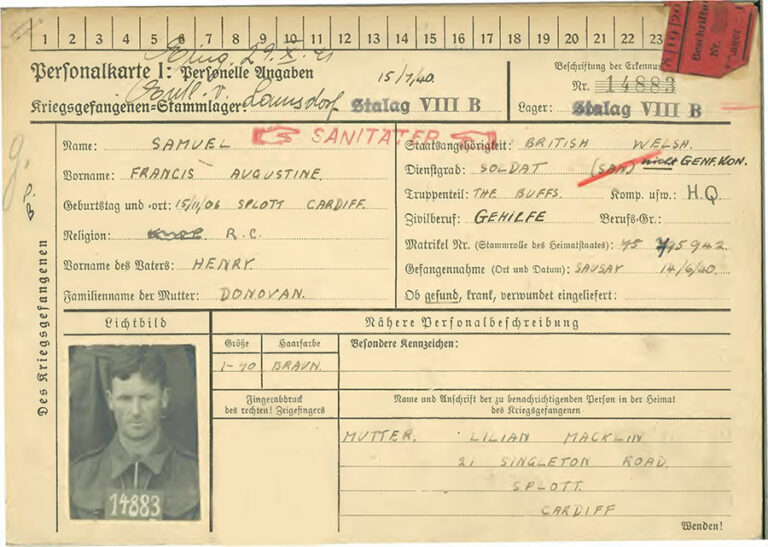

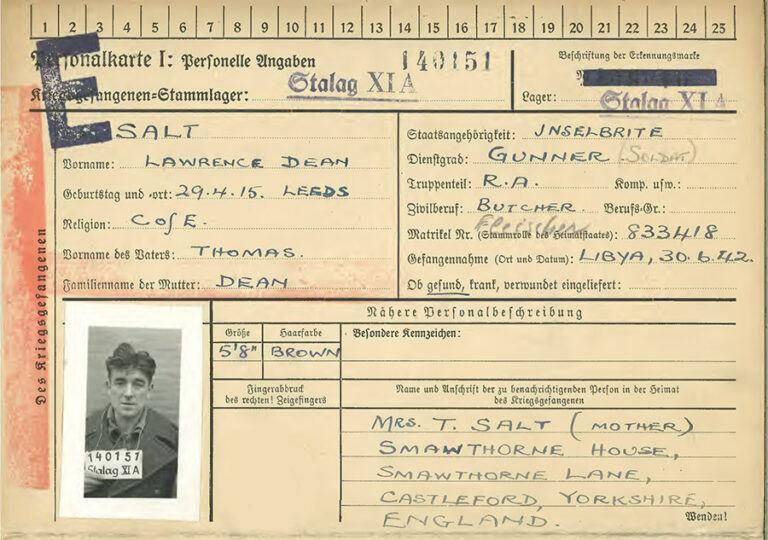

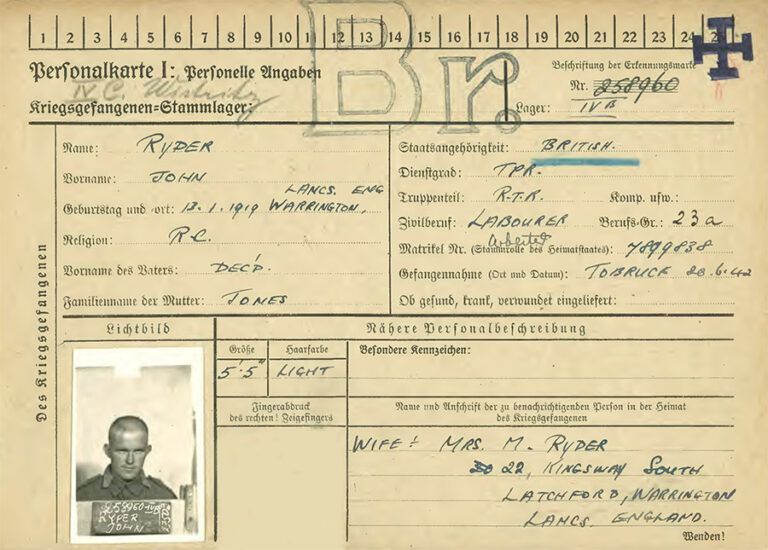

You can glimpse this in the WO 416 series of records. It consists of record cards made by the Germans for Allied PoWs held in ‘stalags’ – PoW camps in German-held territory during the Second World War. For many, there is just one registration card with name, date of birth, rank, nationality, sometimes when and where captured, whether injured or not, and which camps they were sent to, including work camps (Other Ranks were obliged to work). On the reverse of the card was a section on immunisations such as smallpox and typhus, and other medical treatment. Often these reverse sections were not completed. Instead there were smaller pink medical cards, outlining any treatment, and when and where it took place. For some unfortunate PoWs, the cards also record that they died at the camp or at a military hospital.

These records provide a glimpse into the health problems and medical treatment available to Allied PoWs. A huge proportion of PoWs were captured in the retreat to Dunkirk in 1940. This included many injured soldiers who could not be moved, and often with them the brave orderlies and doctors, who gave up their chance of escape to stay with them.

Those who were unable to march were transported from the Front straight to a military hospital (Lazarett). Likewise, airmen shot down, if still alive, might be moved first to hospital before prison camp. The pink cards record their injuries such as shrapnel wounds, gunshot wounds, broken limbs and so on.

Treatment would have been rudimentary: by 1943, the Allies had established that penicillin was much more effective at preventing infection than the widely-used sulphonamide powder and had none of the toxic side-effects. This was not known to the Germany military – ironically one of the penicillin researchers was a German Jew who had fled Germany. So unfortunately, Allied POWs were more at risk from death from infections than injured men who were not captured by the Germans.

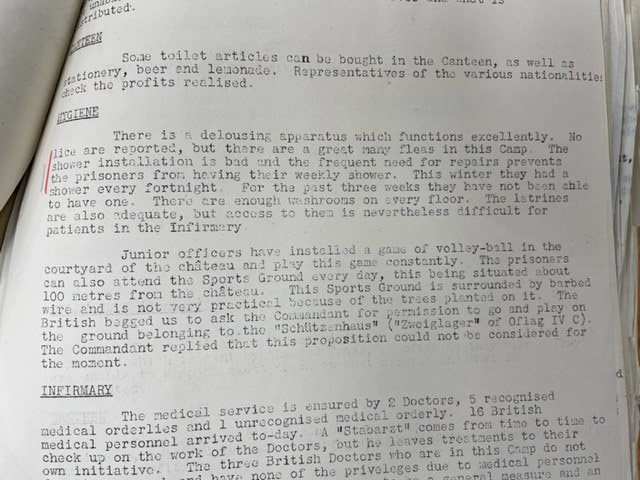

In 1940, those not treated in hospitals, including ‘walking wounded’ were force-marched with little food or water and then crammed into cattle trucks for long periods before arrival in a camp. Accounts of life in camps suggest that they were overcrowded and insanitary, although officers were better treated than other ranks. The journey itself and conditions in camp led to illness. Before Red Cross parcels became available, a combination of poor sanitation, overcrowding, fleas, lice and malnutrition led to illness and deaths from dysentery, jaundice, infections and other diseases. The cards of Allied medical orderlies were often marked with the words ‘San’ for ‘Sanitäter’: the German term reflected German military medical practice at the time, which focused on the role of sanitation.

As the war went on, sanitation and – thanks to Red Cross parcels – nutrition improved, reducing the death toll. The Red Cross parcels may well have saved more lives than any medical treatment.

PoW camps usually had a sick bay (Lazarett or Revier) where infectious illnesses could be isolated and some treatment, often by Allied prisoners with medical expertise. Some even had a dentist. However, visits to a hospital or dentist outside camp were also carried out sometimes. The pink medical cards record a huge range of different issues, many relating to poor nutrition and overcrowding: dysentry, enteritis, through to poor dental health. Dental treatment was basic: tooth extraction.

Where the registration card’s section on immunisation does have an entry, it often refers to a typhus inoculation. PoW accounts tell of delousing powder being used from time to time to reduce the risk of a typhoid outbreak. Other inoculations are less common. However, about 1% of the cards include a chest X-ray and some medical cards refer to checks for tuberculosis.

Although the cards do not make the cause of any injuries clear, some were probably work-related: some soldiers were forced to do dangerous work in quarries or mines. Mental health was also a challenge. Accounts by surviving PoWs tell us that for some, the mental trauma of imprisonment was too much and sometimes a prisoner would be shot dead in a suicidal dash up the wire.

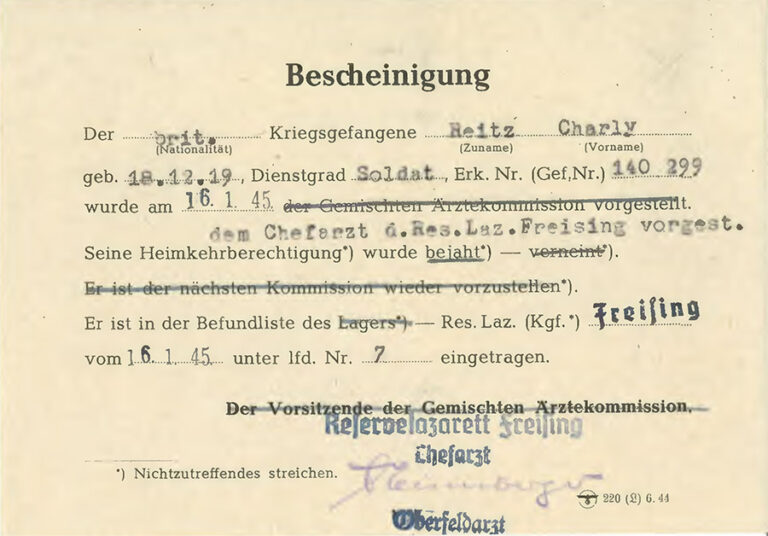

From 1943 there was a limited exchange of prisoners with the Allies through a medical repatriation scheme. In some cases, the WO 416 records include a thin slip of paper that notes the appearance of a particular PoW before a Joint Medical Commission and the decision that that prisoner had qualified for repatriation, although rarely do they give the reason. The route for repatriation is rarely noted on the cards but this was sometimes via Constance (more commonly known as Konstanz) in Germany.

Later in the war, as Germany experienced heavy bombing by Allied plans, some cards that record the death of a PoW note that it was a result of Allied air raids. What the cards do not record was the inadequacy or sometimes total lack of provision of air raid shelters for prisoners. Some places of work were particularly vulnerable but in some cases the PoW camp itself was hit during Allied bombing raids.

Entries on the cards generally end early in 1945. They do not record what happened next. For many PoWs the toughest part of their incarceration was the final stage. Many of the stalags were in the East and as the Russians advanced, PoWs were forced to march hundreds of miles from the Eastern to the Western battle lines through a bitter winter, with inadequate clothing and footwear and very little shelter or food. Some were cruelly beaten or shot by their guards. Some were even shot by Allied pilots, mistaking them for German soldiers. Hundreds, possibly thousands, died on these terrible marches. This was a bitter final burden to bear before liberation.

Find out more

Find out more about Second World War internment and POW records at our free exhibition Great Escapes: Remarkable Second World War Captives. Opening Friday 2 February 2024, Great Escapes explores the human spirit of hope and resilience during times of captivity, revealing both iconic and under-told stories of prisoners of war and civilian internees during the Second World War.

We’ve also scheduled a season of special events to accompany the exhibition that are available to book now.

Further reading

- ‘Medic’, John Nichol and Tony Rennell, Penguin Books Ltd (2010)

- ‘Guests of the Third Reich’, Anthony Richards, Imperial War Museum (2019)

- ‘Survivor of the Long March – Five Years as a PoW 1940-1945’, Charles Waite and Dee La Vardera, The History Press (2013)

- ‘The Last Escape: The Untold Story of Allied Prisoners of War in Europe 1944-45’, John Nichol and Tony Rennell, Penguin Books Ltd (2004)

PLEASE NOTE: Due to the age of this blog, no new comments will be published on it. To ask questions relating to family history or historical research, please use our live chat or online form. We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.

The card for Samuel Leslie clearly shows he was born on 2 November, not 21 November as in the text. Constance (more commonly known as Konstanz) is not in Switzerland but in Germany across on Lake Konstanz from Switzerland.

The book “A Crowd Is Not Company” by well known journalist and reporter Robert Kee covered his experiences as a German POW in World War 2, including being forced to march west at the end of the war. He gives details of the conditions in the POW camps and how the prisoners were treated. I used to have a copy of a paperback version of this book but I can’t find it now. I think my copy must have been published in the 1970s or 1980s.

John Langdill

LOOKING FOR ANYTHING on Stalag 8 and James Nepean O’Hara, Cheers Janet

@ David Matthew – As the article says, the city of Konstanz is in Germany, but it is not on the opposite shore to Switzerland – it straddles the Seerhein (the stretch of the Rhine linking the two halves of Lake Constance) and thus has a land border with Switzerland (which I walked across last week).

PLEASE NOTE: Due to the age of this blog, no new comments will be published on it. To ask questions relating to family history or historical research, please use our live chat or online form. We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.

My father, Sidney Walter Carter was captured on the road to Dunkirk.

He was marched across Belgium and Germany, despite a leg wound, and I believe he spent the entire war in a stalag in southern Poland.

Watching the VE Day celebrations this week has caused me to think of him.

He died in January 1963, and my mother always blamed the lack of food in the camp for his early death.