Westminster Abbey. St Martin in the Fields. St George’s Hanover Square. St John the Evangelist, John Smith Square. Spurgeon’s Tabernacle.

These and other church buildings were among those targeted by the Suffragettes during their militant campaign for suffrage. At Westminster Abbey, a bomb damaged the coronation chair in St Edward the Confessor’s Chapel; at St Martin in the Fields, pews in the south aisle were ripped apart by gunpowder. At St John the Evangelist, stained glass windows were destroyed. At Spurgeon’s Tabernacle, a bomb was left with a postcard bearing the words: ‘Put your religion into practice and give the women freedom.’

All of these ‘outrages’ (as they were dubbed by the press) took place in 1914. But attacks on churches had already started a year earlier, and at one of the most iconic churches in the country: St Paul’s Cathedral.

St Paul’s Cathedral illustration, 1813. Catalogue reference WORK 38/166

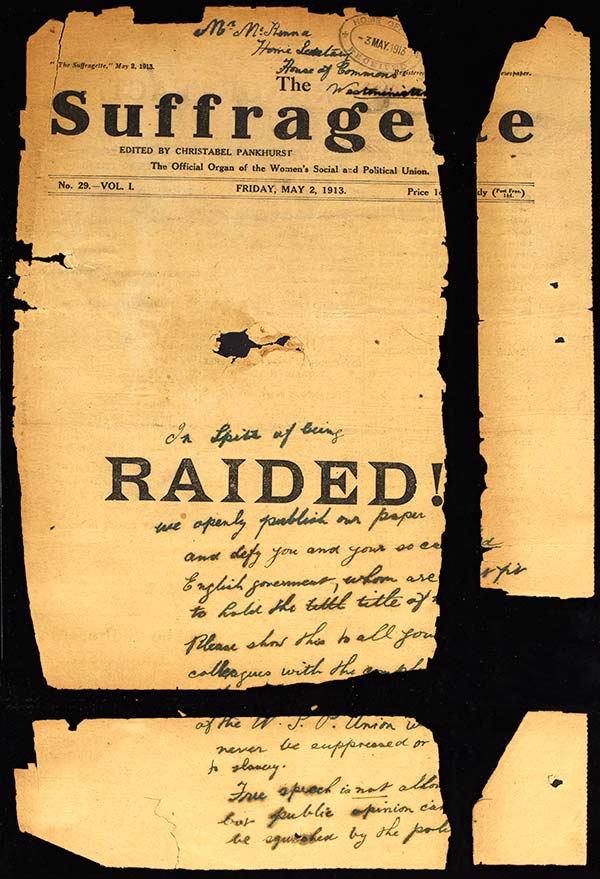

Completed in 1710, St Paul’s Cathedral is the official seat of the Bishop of London. In 1913 the Cathedral authorities were largely concerned with the structural stability of the building, but that same year an additional cause for concern was raised: on 7 May a makeshift explosive device was found behind the Bishop’s Throne in the choir. It was wrapped in brown paper and a page from ‘The Suffragette’, the official newspaper of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), with a message for the Home Secretary.

Front cover of The Suffragette found wrapped around a bomb at St Paul’s Cathedral. Catalogue reference: HO 45/10700/236973

The explicit message, directed to Reginald McKenna, references police raids that had taken place on the headquarters of the WSPU and other associated buildings. You can find out more about the raids in an earlier blog post.

From this it was clear that the Cathedral had become a focus for the Suffragette’s militant campaign.

The package had been found by a Mr Harrison, one of the bell-ringers, while he was cleaning the choir ahead of the morning service. As was recorded by the Dean’s Virger in his diary, the package was ‘placed in a bucket of water and taken into the garden [and] afterwards taken to the police station. On examination it was found to contain an explosive which might have done a good deal of damage to the stallwork’.

The device was later examined by Major A Cooper-Key, HM Chief Inspector of Explosives. Constructed out of an empty mustard tin and parts of an old watch, it was believed that the bomb would have been strong enough to have caused significant damage to the Bishop’s Throne and start a fire. However, according to a letter written by Cooper-Key to Reverend William Newbolt, Canon Residentiary at the Cathedral, on 9 May 1913, the device had accidentally been left switched off. According to Cooper-Key, the design of the switch made it ‘impossible to tell by merely turning the switch whether it was on or off without taking the lid off the box and no interfering with the igniting machinery’, thus explaining why the device had not detonated at midnight, as was the believed plan.

Cooper-Key signed off his letter with hope that ‘there will be no further attempt to injure the Cathedral.’ While he was proved to be correct in this hope, this was not the end of the Suffragettes’ connection with the Cathedral.

In August 1913, the suffrage movement started a peaceful initiative called ‘Prayers for Prisoners’, aiming to interrupt church services to draw attention to the plight of women being force-fed in prison. St Paul’s was the location for a number of these protests, as recorded in the Cathedral archives. The first to be recorded was on Sunday 12 October 1913: it was recorded by Mr Skinner, the Dean’s Virger, that ‘a party of women disturbed the service this morning’.

This simple note belies a more colourful scene, as described in the ‘Dundee Courier’. About 30 women interrupted the prayers to chant: ‘God save Mary Richardson and Jane Short. They are being forcibly fed in Holloway Prison. Their enemies torture them; they know their cause is righteous. Hear us when we pray to thee.’

Just a week later, on Sunday 19 October, another protest took place. Mr Skinner provides slightly more information on this occasion, stating: ‘2 parties of women disturbed the service this morning, they were put out, two of them were charged with assaulting the police outside. At the Mansion House on Monday, one was discharged and the other fined.’ The two women arrested were Rachel Somers and Ruth Kitch. The ‘Dundee Courier’ reported that the constable who made the arrest stated that Somers had kicked him and Kitch had struck him on the neck – although witnesses for the defence claimed that the women had been handled roughly by the police.

The Mansion House Police Court records (held at the London Metropolitan Archives) provide further information: Rachel Somers (23) received a fine (of £3), while Ruth Kitch (29) was discharged. Both women can also be found in the ‘Index of Women Arrested 1906-1914’ (HO 45/24665), which is held at The National Archives and is currently on display as part of the exhibition Suffragettes vs. the State which is open until 26 October 2018.

Several other suffrage protests are recorded in the Deans’ Virger’s Diaries. After the events of October 1913, it seems the women were not interfered with, although on one occasion – on 14 June 1914 – during the afternoon service,one of the protestors chained herself to one of the chairs, ‘which had to be sawn’.

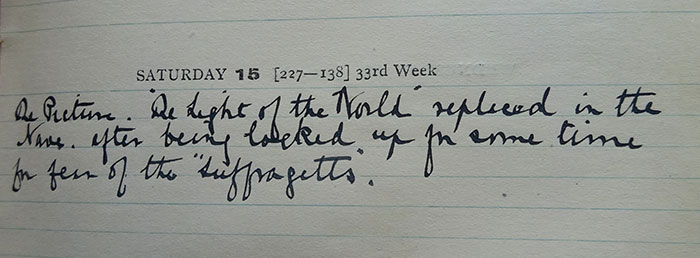

In addition to the peaceful prayer protests, the Cathedral also clearly anticipated protests of a more destructive nature. Mr Skinner relates in his diary of 15 August 1914, 11 days after Britain’s declaration of war with Germany, that William Holman-Hunt’s ‘The Light of the World’ – the painting of Christ that had been given to the Cathedral in 1908 – was ‘replaced in the Nave after being locked up for some time for fear of the “Suffragettes”’. We do not know the date at which the painting was taken down, but presumably it was sometime after 11 March 1914, when Mary Richardson (previously prayed for by Suffragettes at the Cathedral in 1913) damaged Diego Velazquez’ ‘Rokeby Venus’ at the National Gallery.

Page from Dean’s Virger Diary, 15 August 1914 (no ref.). St Paul’s Cathedral Archive, reproduced by permission of the Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

The return of the ‘Light of the World’ marked the end of the suffrage protests at the Cathedral. The movement to fight for women’s right to vote finally succeeded through two laws passed in 1918 and 1928. St Paul’s later became the focus for discussion about female ordination, with some of the first women priests being ordained at the Cathedral in 1994. And, of course in 2018 – over 100 years since the Suffragettes made their attempt on the Bishop’s Throne – the very first female Bishop of London, Reverend Dame Sarah Mullally, was installed and able to take her place on the very same throne.

Sarah Radford is the Archivist and Records Manager at St Paul’s Cathedral. The archive collections on site at the cathedral contain records relating to the activities of cathedral clergy and staff dating from the 19th century to the present day, while older records dating back to the medieval period are held at the London Metropolitan Archives. Further information about the cathedral’s history and historic collections can be found on the St Paul’s website and you can find out more about the suffrage ‘outrage’ at St Paul’s at an upcoming event at the Cathedral.

You can find out more about records relating to women’s suffrage at The National Archives on our Suffrage 100 page.

Mary Richardson later ran the Woman’s Section of Mosley Fascists and it would be nice to use Jane Short’s real name. The Suffragettes held no respect for the ‘House of God’ and nobody put them on hunger strike, they did it themselves. TNA should stop calling it ‘Outrages’, it was terrorism.

Terrorism or not (the academic debate on this still rages), these women were not pursuing some minority religious ideology, they were fighting for the equality for half of the population. Would men not have battled similarly if they had found themselves in similar circumstances?