On 30 September 1916 ‘between 2,000 and 3,000 of the women employees of the Lancaster National Projectile Factory struck work as a protest against the dismissal of a girl. The girl had been dismissed because of misbehaviour with a male employee, who, however, had been allowed to remain in the factory.’ The Ministry of Labour reported they ‘anticipate the possibility of further trouble.’ [ref] 1. Catalogue reference: MUN 2/27 [/ref]

As my colleague Chris has previously demonstrated, the First World War brought unique, if limited, gains to women in the labour movement. Women appear to have developed a stronger understanding of their own labour rights and many were able to use the arbitration systems and government edicts on equal pay to protest against unfair treatment.

However, other methods also became necessary. Even in the patriotic climate of war, many women turned to striking.

What motivated women to strike?

Our records document a significant number of intriguing, small-scale, self-organised strikes by female workers over a diverse range of issues. Women’s strikes are surprisingly common with one report noting that the women were ‘jumpy’ and might strike again at any time, and another observation attributing the labour unrest in London to ‘nervousness’ caused by air raids.

The entries in the Ministry of Munitions digests (MUN 2) are frustratingly brief but capture the essence of why a group of women, or men, were striking. The types of strikes that can be found in the digests are hugely varied in both size and motivation. Several entries provide an idea of the different types of industrial action that were taking place across the country.

I’m going to look at a selection of types of strikes – particularly those outside the issue of equal pay that were the focus of our last blog post.

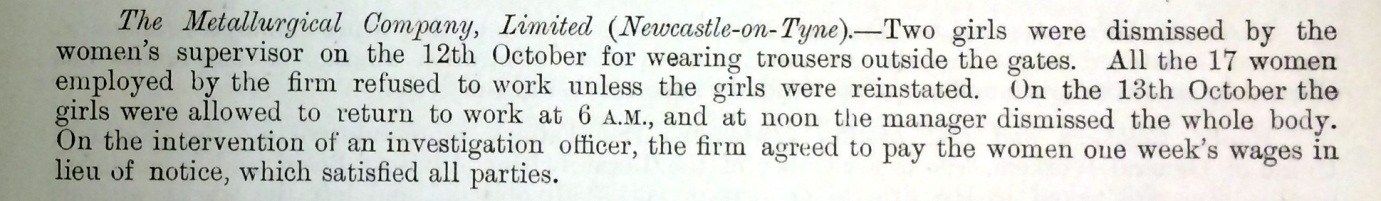

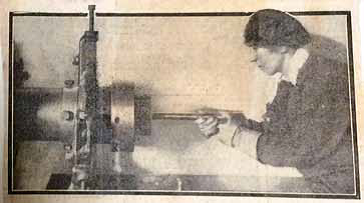

Image from the government publication Women’s War Work, September 1916 (catalogue reference: MH 47/142)

Variety of strikes

On 12 October 1917 at the Metallurgical Company in Newcastle two ‘girls’ were dismissed for wearing trousers outside the gates of the company. In reaction all 17 women employed by the firm refused to work unless they were reinstated. Ultimately the ‘girls’ were allowed to return to work, but by noon on their day of return the manager had dismissed all of the women. This illustrates a small scale strike based around a collective sense of justice for the dismissed workers. Though the initial issue was small it was enough to empower the 17 women workers to strike, albeit unsuccessfully. Small groups of women clearly felt legitimised to strike even in the context of the patriotic home front. The concern was about localised issues that affected their everyday lives.

Description from the munions digest of the Metallurgical Company strike (catalogue reference: MUN 2/28)

There are also examples of larger strikes, again over issues besides equal pay. On 3 November 1917, 900 men and women engaged in aircraft work took strike action over the change in tea time for charwomen employed by the firm Messrs. Petters. Unfortunately, the ultimate outcome is not detailed in the digests. However this shows a larger scale strike that would have had a significant impact on a workforce who were directly producing items of importance to the war effort.

Description from the munions digest concerning the tea time of charwomen (catalogue reference: MUN 2/28)

Although a remarkable number of the strikes listed in our collections are men striking against women’s movement into the workforce, there are a notable number of sympathy strikes by male workers in support of their female colleagues. This strike in particular is noted for the men who took action in support of the charwomen’s tea time, a workplace-specific dispute of importance to the women involved.

Other common themes that recur in these records are objections to a foreman or forewoman, and issues over equal pay. The range of strikes is incredibly varied and very surprising considering the patriotic narrative of the home front that is most commonly thought of.

Women’s Union involvement

There are many strike summaries in the digests that note the role of the Federation of Women Workers. For example, on 18 February 1916, 2,500 young girls at the Greenwood and Batley’s cartridge factory struck over issues of pay, principally the excessive difference between the highest and lowest wages earned; the firm called the action ‘unorganised and irresponsible’. Leaflets were noted to be distributed by the Worker’s Union and the National Federation of Women Workers urging the workers to join their unions. These unions were highly active throughout the war, despite anti-union legislation trying to prevent disruption to the workforce under the Defence of the Realm Act.

On 3 November 1917 the National Union of Women Workers took on a case of victimisation involving 21 women dismissed from Thos. Summerson and Sons in Darlington after two attended an arbitration tribunal between the company and female workers. The firm offered to swap the individuals in question for the dismissal of two alternative girls; the National Union of Women Workers demand the reinstatement of all 21 women, and summoned the firm before a munitions tribunal on the question of victimisation.

As 90% of trade union members were male at this time, the implementation and exercising of these rights signalled a remarkable mobilisation of women in the labour force. [ref] 2. TUC History Online: unionhistory.info/timeline/1880_1914.php [/ref] These digests indicate that women’s patriotic war service is an oversimplification, particularly in reference to those women among the working classes who were clearly willing to significantly disrupt wartime production to insist on their rights.

While work needs to be done to analyse the success rate of these strikes and the percentage of strikes involving women, the digests are undoubtedly a rich source of information that diversify our view of the First World War.

Gaining labour rights

Hopefully this small blog series from me and my colleague Chris has demonstrated that the introduction of arbitration tribunals and the work of the grassroots and national unions enabled small but significant gains for women workers.

Women are often described as moving in to the workforce in a show of loyal support for the war effort. However, the prospect of better pay was often a significant motivating factor for many women, as shown by their readiness to strike. The war created a legacy for female munitions workers: a sense of greater value as part of the workforce, and an increased understanding of the government processes through which labour rights could be fought.

The National Archives’ records on women’s workplace arbitration continue into the late 1920s. This laid the groundwork for further struggles for equality and fairness for women in the workplace.

Fabulous stuff: well done for mining this particularly rich little vein.

The sentimentalised and a pro-One-Nation political perspective of much commentary is being challenged very satisfyingly by this sort of small-scale research.

Of course working-class women wanted better wages and many of them took the harsh and sometimes dangerous conditions (e.g. ‘canaries’) because of that very understandable urge.

Even in 2016 we still have average female wages 14% below men’s.

The National Archives is a beacon of hope in our increasingly bleak public cultural landscape and I frequently refer people, particularly writer/historians like myself, to your newsletter for information and inspiration.

Thanks again.

It wasn’t the case that the women wanted better pay, they wanted equal pay, they were doing the work of the men who were taken off to war, the women were doing the same work as the men, dirty heavy repetitive work, with the worry of their menfolk at war, and still had to go home to look after their families. So why shouldn’t they be payed the same rate.

What an interesting article which shows how long women have been protesting against unfair treatment in the workplace. Thanks to the researchers for their hard work in bringing this fascinating information to light.