Charles Voysey in the 1860s Wikicommons

To me, ‘The Sling and the Stone’ seemed an odd entry to find in The National Archives’ catalogue in the records of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. I came across it by chance and felt compelled to take a look at the documents. A bit of reading revealed a story of unorthodox ideas and the wilder fringes of political activism and publishing.

‘The Sling and the Stone’ turned out to be the text of a series of sermons written by the Reverend Charles Voysey, an Anglican vicar, during the 1860s and 1870s. At the beginning of the 1860s, he was ministering in Whitechapel, but lost his post after preaching against the doctrine of eternal punishment. He found another appointment at Healaugh in Yorkshire and, in this in this rural setting, he continued to preach and publish controversial sermons against the validity of the Bible and the divinity of Christ.

The Church soon caught up with the dissident preacher. Voysey was tried in the ecclesiastical courts in York and found guilty of heterodox teaching. Determined to hang on to his post, he took an appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in 1871. He failed, and once again he was out of a job. Some evidence put before the Judicial Committee, including two volumes of ‘The Sling and the Stone’ (not an easy read) can be found at PCAP 1/423.

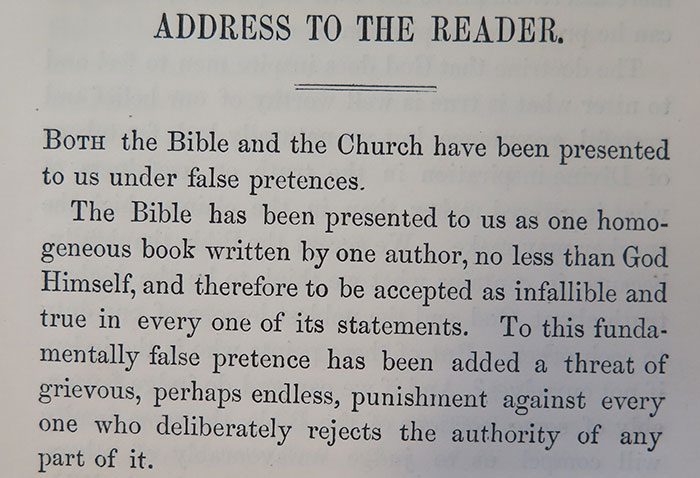

Voysey’s provocative ‘Address to the Reader’, The Sling and the Stone, Volume 2 (Trübner and Co, 1867) PCAP 1/423.

But Voysey was a determined man and apparently quite well off. He established his own Theistic Church at Swallow Street in the West End of London. He acquired a substantial congregation and continued to preach theism until his death in 1912, when over a million copies of his sermons had been sold (Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, “Charles Voysey”). His son, C F A Voysey – who became a prominent architect – carried out extensive work to the interior of the Swallow Street church.

During his time at Swallow Street, probably in 1902, Voysey met a youth by the name of Guy Aldred – a committed Christian and public speaker, already known in the East End as the ‘Boy Preacher’. Aldred had been drawn by Voysey’s ideas. What exactly passed between the elderly Voysey and the youthful Aldred in their conversations over the next few years is uncertain, but Aldred dropped Christianity and emerged from the early 1900s as an atheist and anarchist. A Home Office file reports that in February 1907 he spoke at a meeting of anarchists at New Alexandra Hall, the headquarters of the Workers’ Friend group of anarchists (HO 144/22508, 20 July 1916).

I found that The National Archives holds several files on Aldred. His anti-imperialism, pacifism and opposition to organised government – and especially his passion for speaking and publishing – often landed him in trouble with the law. In fact, Aldred was inconsistent in his ideas throughout his life, but in 1909 he defined himself as

‘an Anarchist Communist …..I stand for the overthrow by industrial-political anti-constitutionalist action of class-society, and for the inauguration of a social era in which the government of persons shall have give place to the administration of things.’ (The Indian Socialist, Vol V, No 8, p. 31 CRIM 1/114/4)

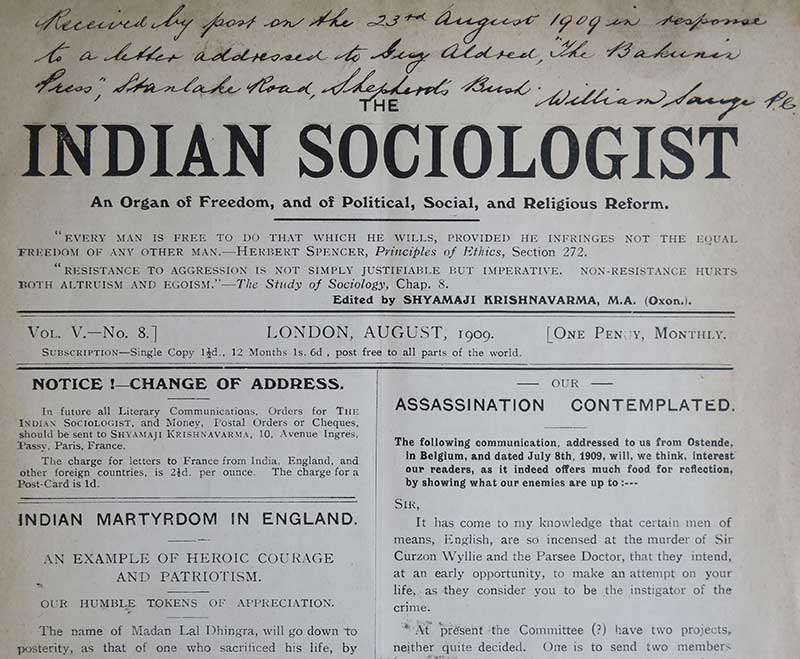

The August 1909 edition of The Indian Sociologist, for which Aldred was prosecuted (CRIM 1/144/4).

Aldred’s first major brush with the authorities occurred in 1909. He edited the August 1909 edition of The Indian Sociologist, a publication with the goal of independence in India. The edition defended Madan Lal Dhingra’s assassination of Sir William Curzon Wyllie, former Indian Army officer and India Office official, and attacked the British administration. He was sticking his neck out here, as the previous editor and already been jailed and the paper’s owner, the independence campaigner Shyamaji Krishna Varma, had taken refuge in in Paris. Aldred was duly arrested and accused at the Old Bailey of sedition. Found guilty, he was sentenced to a year in prison (CRIM 1/114/4).

Guy Aldred during his first visit to Glasgow, 1912. Source: Guy Aldred Collection, Strathclyde University Special Collections

By the outbreak of the First World War, Aldred was the editor of an anarchist journal called The Spur. As a committed pacifist, he became a conscientious objector and served the remainder of the war years in prison, while Rose Witcop (his partner and a birth control campaigner) took over as editor. Released from prison early in 1919, he resumed editorship and, moving between London and Glasgow, gave many speeches castigating the government and calling for revolution. He received a further year’s sentence for sedition in June 1921.

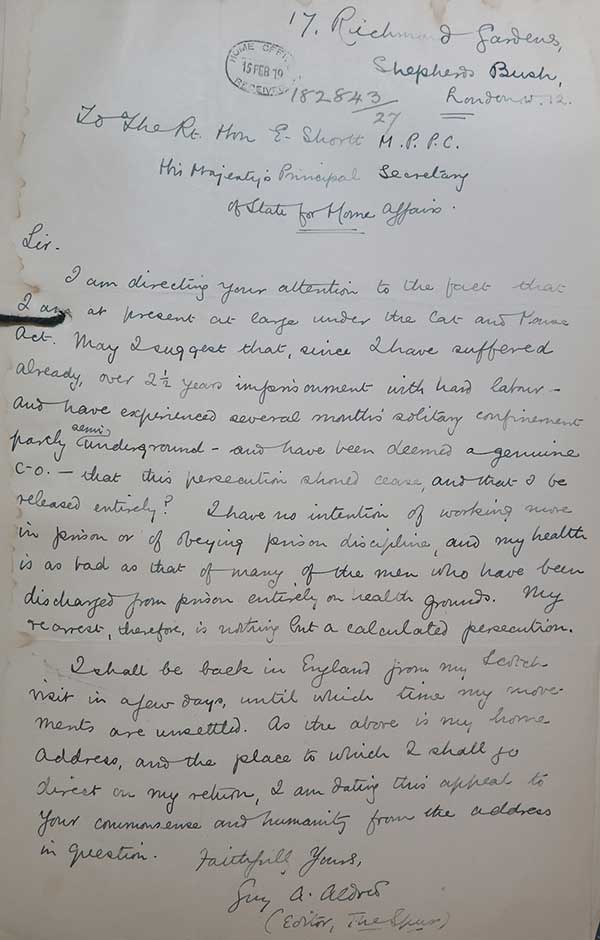

Aldred’s letter to the Home Office of February 1919 requesting discharge from further imprisonment (HO 114/22508).

In 1925, Aldred’s Home Office file reports an inflammatory speech made in Hyde Park (HO 114/22508), but afterwards he is absent from the official records until just before the Second World War, when he came under the observation of the Security Service. By then, he was closely associated with the anarchist United Socialist Movement and had unsuccessfully stood for public office.

In 1938, Aldred was at a low ebb, but he inherited £3,000 from Sir Walter Strickland, a wealthy supporter of anarchist causes. He used this windfall to establish The Strickland Press, which issued many publications, including a United Socialist Movement’s journal, The Word. Aldred used The Word to campaign against Britain’s involvement in the Second World War and formed an alliance with another wealthy backer, the Duke of Bedford, who was thought to have fascist sympathies.

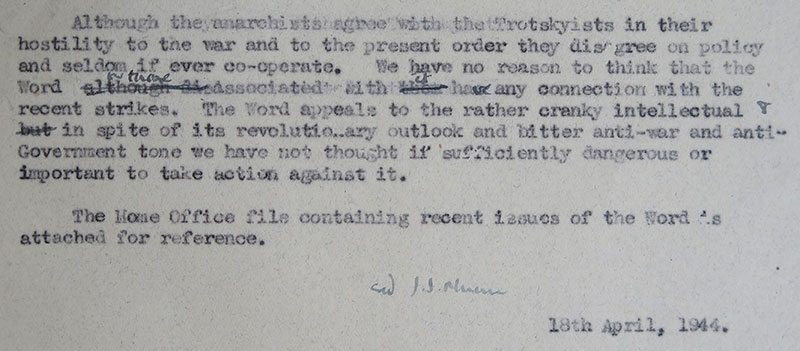

A Home Office memo discounts Aldred’s significance (KV 2/782)

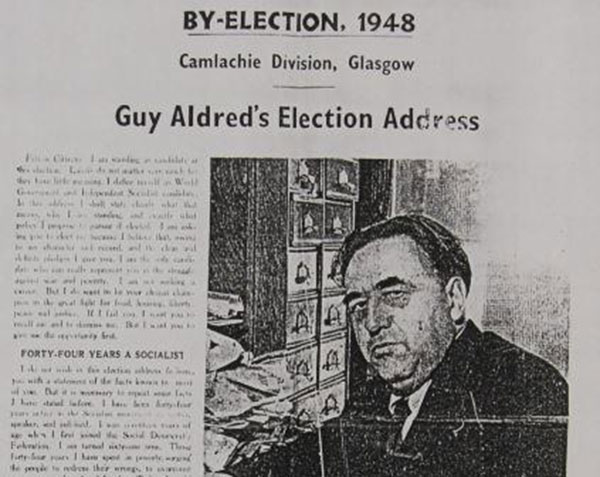

Consequently, the Security Service had Aldred under observation throughout the war years. The Security Service urged the Home Office to take action against Aldred, but officials there saw in him little threat. In spite of The Word’s ‘revolutionary outlook and ant-war and anti-government tone’, it seemed to appeal only to ‘the rather cranky intellectual’ (KV 2/792). At the end of the war, officialdom lost interest in Aldred, and at that point he disappears from the records. Nevertheless, he continued to publish and campaign – standing unsuccessfully in the Camlachie by-election of 1948 – until his death in 1963.

Aldred’s election address for the Camlachie by-election in 1948 (KV 2/792)

Linked by the surprising connection between Voysey and Aldred, these records provide an insight into unorthodox thinking, publishing and protest in Britain. But there is a lot more available elsewhere, as is revealed by a search of Discovery, our online catalogue. Aldred produced an unfinished autobiography in ‘No Traitors’ Gait! – The Life and Times of Guy A. Aldred’, while his close associate at the Strickland Press published a biography in ‘Come Dungeons Dark: the Live and Time of Guy Aldred, Glasgow Anarchist’ (1988).

Sir, researching the life of Sir Walter Strickland (in connection with the “pro India” committee of 1912-1914 in Zurich), I read with interest your piece on Aldred, saying that Aldred inherited £3’000 from Sir Walter. An other information says that Aldred was trustee of Stricklands bequest (Evening Chronicle, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 11 Aug 1939, Page 12). Albert Meltzer, in his auto-biography “I Couldn’t Paint Golden Angels: Sixty Years of Commonplace Life and Anarchist Agitation” (1969) even claims, that Strickland’s relatives challenged the will in court, of what I could not find any trace. Do you have more precise informations on this item? Or at least the primary source for the £3’000 heritage? I would be very appreciative for it.