For the first time in seventy years, and for many of us perhaps for the only time we will experience it, this year will witness a royal coronation in the UK. As attention at home and around the world turns to the enthronement of King Charles III in Westminster Abbey on 6 May, we can be sure that the ceremony has been long in the planning.

The new king will wish to put his own stamp on the ceremony, having expressed his desire for a pared down coronation that reflects the monarch’s role today and look towards the future, while being rooted in longstanding traditions and pageantry (see footnote 1).

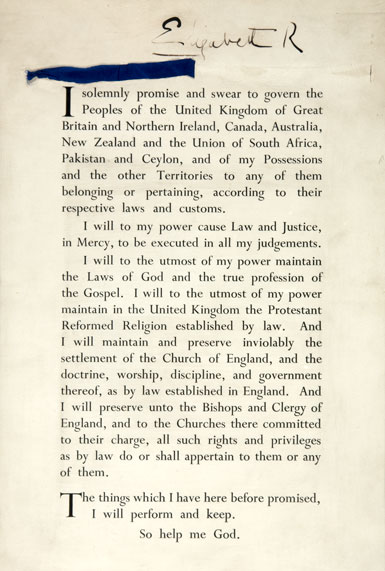

King Charles will swear an oath that retains some of the monarchical traditions of centuries past, similar to that sworn by Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. The new king will also don robes and carry regalia not very far removed from those of his ancestors.

Among the many millions of original records in our collection, The National Archives holds a huge variety that document royal expenditure on ceremonial from the early twelfth century onwards. Two of these will form the first display in our new initiative called Stories Unboxed: A One Document Display.

Stories Unboxed will exhibit one or more of our original records on the first floor of our building in Kew – and share their stories online too – to highlight topical finds and lesser-known treasures from our collection.

One of our documents is closely tied to the coronation of the last King Charles, the other is important not simply for its contents but also for its materiality and as an object which conveys memory across time.

Record 1: Robing the king

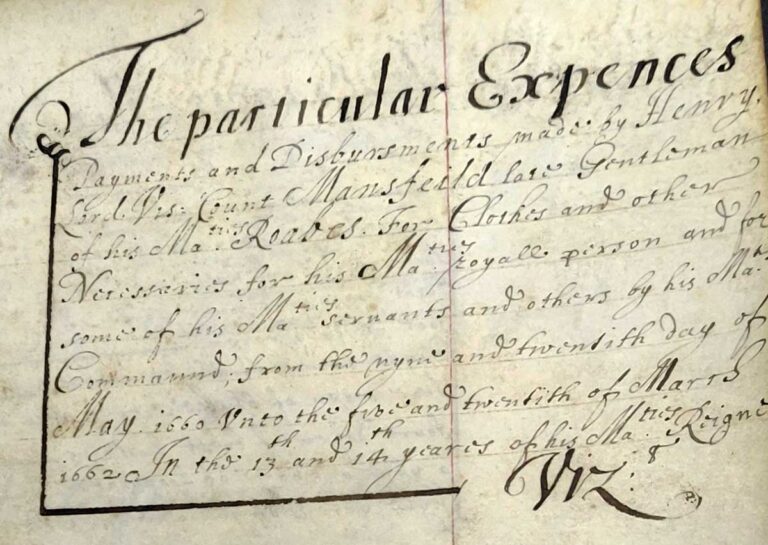

Our first exhibit is the account book of Henry Cavendish, second duke of Newcastle and Viscount Mansfield, Gentleman of His Majesty’s Robes. It records the expenses of robing the king and some of his servants from 29 May 1660, the day upon which the restored king Charles II had ridden triumphantly into London to reclaim his throne, to 25 March 1662.

On St George’s Day (23 April) 1661, Charles II was formally crowned king of England in a lavish ceremony at Westminster Abbey. On the previous day he had processed from the Tower of London to Westminster, the last monarch to experience such a joyous ritual.

He had chosen, compelled by circumstances related to the collapse of the Commonwealth and the restoration of his kingship, to wait almost a year before his coronation. Image making and display were as critical elements of premodern monarchy as they are today.

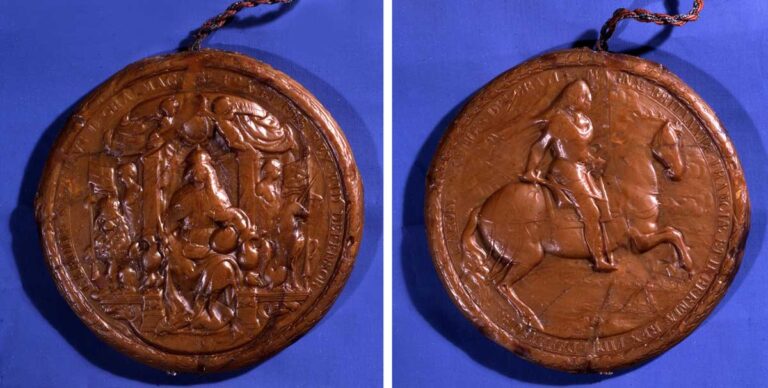

Another reason for the delay of the ceremony, now under the Anglican rite, and the swearing of the new king’s long-anticipated coronation oath, was the need to provide new jewels and regalia. Some had been melted down during the Commonwealth, and ceremonial robes for the occasion had to be acquired. The costs to the royal treasury were astronomical. Over £12,000 was spent on the ceremony itself, and expenses for robes accounted for a good chunk of this.

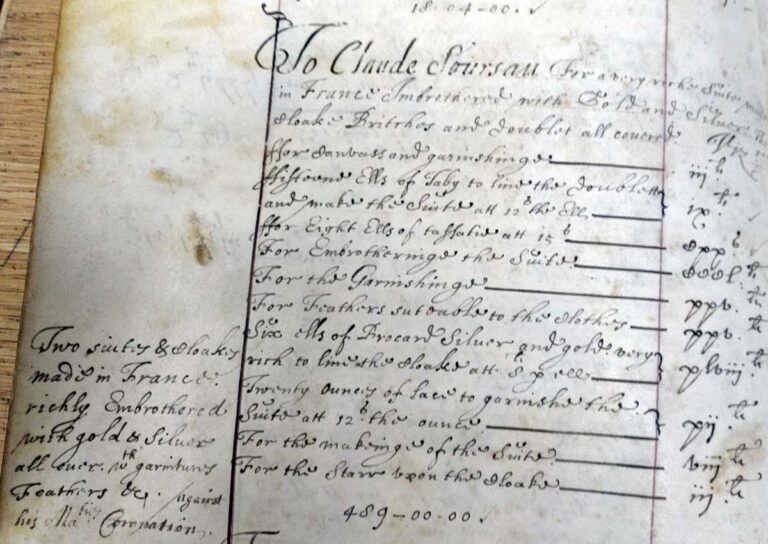

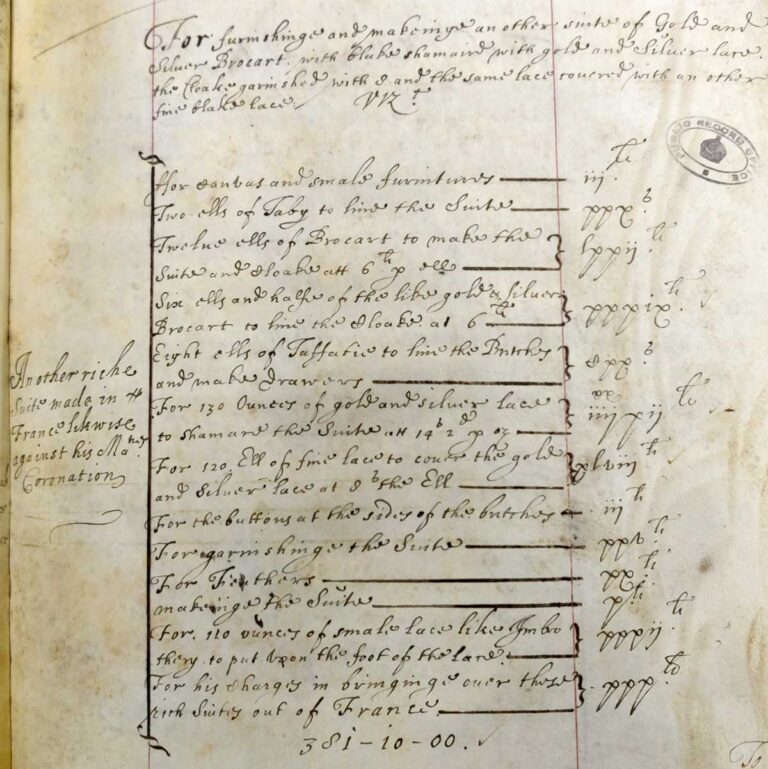

Mansfield’s account carefully records the expenses of tailoring the king’s coronation robes. The renowned French tailor Claude Sourceau was commissioned to make several items, including ‘Two suites & Cloakes made in France, richly Embrothered [embroidered] with gold & silver all over, with garnitures, Feathers etc. against his Majesties Coronation’ and ‘an other suite of Gold and Silver Brocart with blake shamaire with gold and Silver lace’.

Taken together, the tailoring and transportation of these three suits cost Charles £1,320, approximately £150,000 today, or the equivalent of almost 19,000 days’ labour by skilled tradesmen (see footnote 2).

Charles had spent some of his youth in exile with his mother Henrietta Maria in the Louvre Palace in Paris, and was enamoured with French fashions. The first of the suits, made up of three cloaks, britches and doublet, cost Charles an eye-watering £489.

Exotic cloth was used, including fifteen ells (equivalent to about 45 inches) of tabby, a heavy, striped silk cloth imported from the Near East, and eight ells of taffeta, a similar, if lighter silk cloth made mostly in Europe (see footnote 3). The suit was garnished with suitable feathers and silver and gold brocade, as well as twenty ounces of lace. Note of a ‘Starr upon the Cloake’ suggests the embroidering of the Star of the Garter, the chivalric order founded by Edward III in 1348.

The second suit is described as ‘… an other Imbrothered Suite six Ranckes upon the Cloake tenn upon the Britches the doublet all covered, the rest of the bottome of the Stuffe Embrothered with gold upon a Nett of Silver’. It cost a total of £450 for Sourceau to craft, including £311 on embroidery.

A third suit as lavish as the others was also purchased. Both tabby and taffeta were again employed with a significantly greater quantity of lace, some even of gold and silver. The king was provided with button-up britches for his added comfort and convenience. A final item in the account notes the expenditure of £30 on transportation of the robes from France to London. English tailors were not excluded from providing fine robes for the coronation but Sourceau was given the primary commission.

The king’s precise coronation array is uncertain but the effect created by these robes must have been appropriately dazzling, and set the seal on a bold new era in courtly fashion. In our age of mass- and multi-media we will be given intimate insights into the fashion choices of our new king, his consort and the royal family before, during and after the ceremony, not to mention the expenses incurred in mirroring the pageantry and symbolism of previous coronations.

While the future of the monarchy here and in the Commonwealth is a matter of intense public debate and interest, King Charles III does not have the same problem as his namesake – to have to create an impression on a country violently stripped of its monarchy, looking to restore its lost lustre and reputation amid a maelstrom of religious and political turmoil. For Charles II, his coronation was a major step in reasserting and consolidating the aura of majesty, and the robes and regalia he chose played no small part in that.

Record 2: The ‘Hairy Wardrobe Book’

Our second document on display as part of Stories Unboxed takes the story of royal courtly expenditure back to the Middle Ages. As a medievalist who lives (metaphorically) in the fourteenth century, it is my personal favourite document in our entire collection.

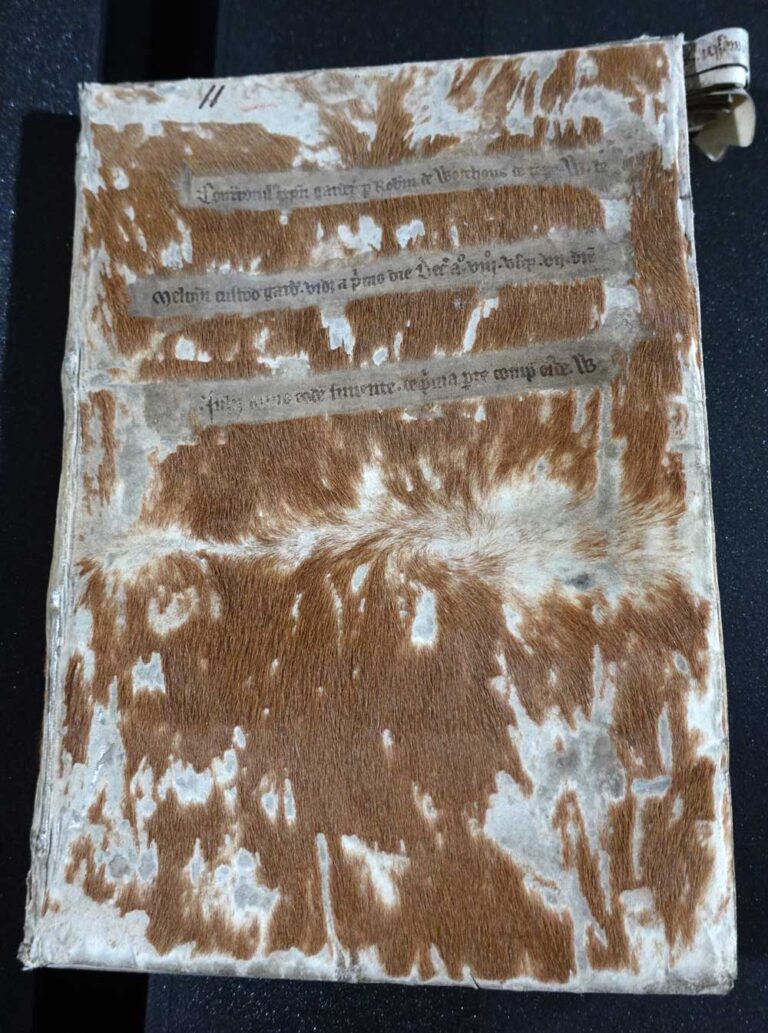

Among colleagues it is commonly known as the ‘Hairy Wardrobe Book’ – for obvious reasons. Bound in an unusual deerskin cover, in its original medieval limp vellum binding, is the account book of Robert de Wodehouse, deputy keeper of the Wardrobe of King Edward II (1307–27).

Consisting of over 100 folios of high-quality parchment – animal skin, usually sheep or goat, but in finer examples calf – this is one of the best surviving examples of the recordkeeping practices of the Royal Wardrobe. It gives us rich details of how the king’s provisioning department functioned.

At the time the royal secretariat, the Chancery, recorded copies of outgoing correspondence and royal grants on long parchment rolls, membranes stitched at the top and the bottom and rolled up rather like a toilet roll. The royal financial department, the Exchequer, wrote their final audited accounts onto larger skins of parchment sewn at the head only and used like a modern flipchart. The Wardrobe, however, adopted the book format from at least the 1280s, possibly due to the influence of Edward I’s Italian merchant bankers.

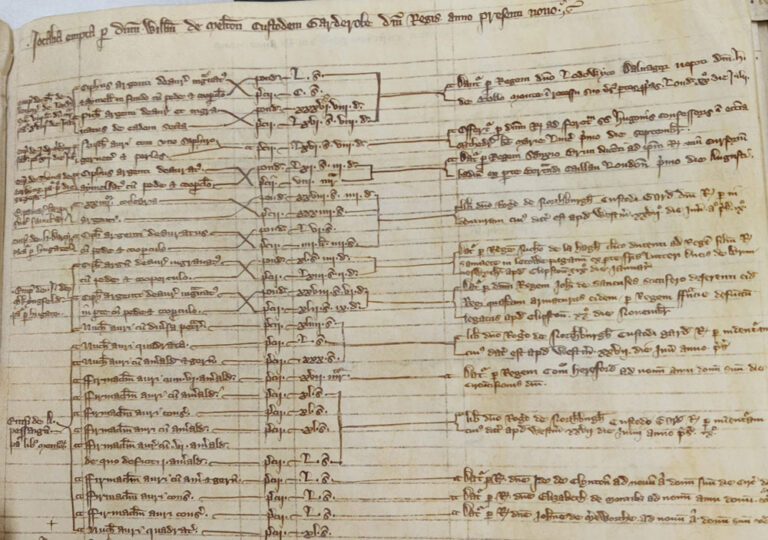

The account book is written up in sections (or ‘Titles’) according to the different departments of the Wardrobe and/or the wages of various household servants. So, to name but a few, there are alms (charitable giving), messengers, minor necessary expenses, the wages of falconers and huntsmen, robes and jewels, and plate.

Sticking with the theme of robes, that year Edward II’s Wardrobe spent £627 on the robes of members of the royal household, whether knights, clerks or other officials. The bannerets, the senior knights entitled to bring a company of his men onto the field under their own heraldic banner, received robes worth eight marks (£5 3s 4d) and the ordinary knights received robes worth four marks (£2 6s 8d).

These men were not only those who served with the king in war but often undertook royal commissions to impose his justice in the shires or enquire, for example, into breaches of river and sea banks or ditches. They were entitled to wear his livery and would have made an imposing sight both at ceremonial events and as the king travelled around his realm.

The Royal Wardrobe was one of the repositories for storing royal regalia and jewellery. In the Jocalia (or ‘Jewels’) section of the annual account we find a longish list of cups – some silver, others silver gilt – and enamelled brooches and rings. Each item is listed in terms of both its weight and its monetary value. Some are annotated with details of the individual to whom the king has gifted it.

For instance, on the list is a gold brooch encrusted with a sapphire, garnet and pearls, valued at 66s 8d, bought from the Exchequer clerk John of Markenfield. It was offered by the king at the shrine of St Hugh the Confessor in the cathedral church in Lincoln on 1 September 1315, during a fractious session of Parliament, as debates over the king’s finances raged (see footnote 4).

Another gold brooch encrusted with six emeralds was gifted by the king to the earl of Hereford at New Year (1 January) – the traditional moment for gift exchange at court in this period.

To give an idea of the scale of annual expenditure at the time, which coincided with the first year of a devastating European famine, Wodehouse accounted for a total of £5936 10s 8d for almost seven months from 8 July 1315 to 31 January 1316. At a time of straitened financial circumstances this is testament to consumption at the royal court, even if at a lower level than earlier years.

How the monarch raises and spends their income has always been a topic for debate in Britain. In this first pair of documents put on public display for our Stories Unboxed programme, we hope researchers and visitors will enjoy a new window on to the documentary heritage of premodern Britain, and the chance to experience their materiality in close-up.

Stories Unboxed will bring iconic and never-before-exhibited records into public view from the beginning of April. Each month, record specialists will share their knowledge of our collections with pop-up talks and online content. If you visit us, don’t miss this opportunity to glimpse into the past, as we showcase more stories from our collections.

Footnotes

- The Coronation of His Majesty The King: https://www.royal.uk/coronation-his-majesty-king

- The National Archives, Currency Converter: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/#currency-result. Please see the disclaimer for details of how these figures were calculated

- For definitions of cloth and clothing terms see The Lexis of Cloth and Clothing database: http://lexissearch.arts.manchester.ac.uk/

- J.R.S. Phillips, Edward II (New Haven and London, 2010), pp. 250-2

The Library at The National Archives has a selection of publications relating to Coronations that are available to read on site during your visit – you can find the list of titles here – https://tna.koha-ptfs.co.uk/cgi-bin/koha/opac-shelves.pl?op=view&shelfnumber=326

A fascinating read – I look forward to visiting this display. And also to viewing the accounts for King Charles III’s coronation.

“Stripped silk” or striped?

Thank you – you’re quite right. We’ve changed this to ‘striped’ now.

A gold brooch is mentioned gifted from the king to the Earl of Hereford on New Year’s Day, marked as 1 January. In the early 14th century wouldn’t the new year start on Lady Day, 25 March (Julian calendar), so 1 January would just be one of the twelve days of Christmas?