Today, we have released almost 600 Cabinet Office files covering Tony Blair’s Labour administration (PREM 49). 170 of them have been digitised, and can be downloaded from Discovery, our catalogue.

The files, predominantly covering 2001 and 2002, shed light on a range of subjects both at home and abroad under Tony Blair’s leadership, giving a snapshot of what was happening 20 years ago and at the turn of the century.

‘Unless we find a genius, one person alone won’t fulfil all these tasks’

One of the joys of Cabinet Office file releases are that they give us an insight into what the people at the very top of government, including the Prime Minister, really thought as they made huge policy decisions.

PREM 49/1818 is one of several ‘DOMESTIC POLICY: strategy’ files released today. It is unusual and remarkable in containing two long, typescript memos, as well as many candid marginal notes from the Prime Minister, when usually the occupants of Number 10 confined themselves to short notes and ticks as they waded through the mountains of papers in their red box.

PREM 49/1818 opens on 15 June 2001, eight days after Tony Blair’s government had won a second term in office after the general election of that year. It predominantly contains memoranda circulated between Blair and his closest advisers, as they charted the priorities and dangers of his second term in office.

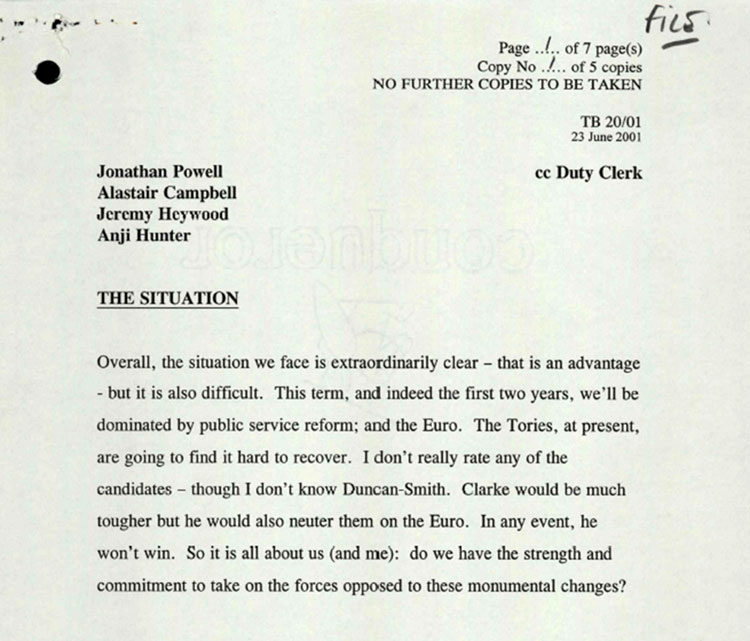

On 23 June 2001, Blair circulated a memo on ‘the situation we face’. The Prime Minister believed that, after a convincing general election win, there was ‘an advantage – but it is also difficult’, as he laid out what he wanted to do, and what he was worried about during his sophomore ministry. Blair identified wide-ranging public service reform as his key goal, while also highlighting potential pitfalls around the Hunting Ban, the Euro, and disagreements with the Treasury.

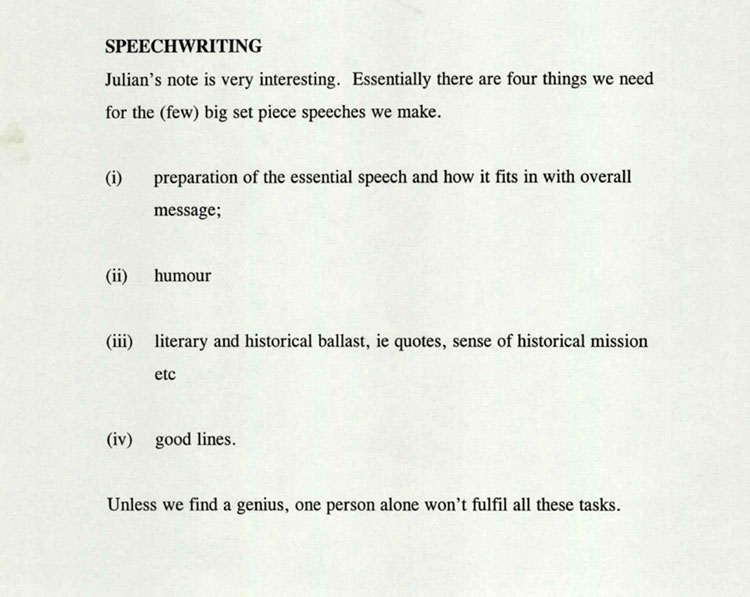

Blair and his advisers were not only concerned with strategies for policy, but with how they would convincingly present them, not least in speeches. In the same 23 June 2001 memo, Blair provided a wish list for what the perfect speechwriter would bring to scripts for him: ‘(i) preparation of the essential speech and how it fits with overall message; (ii) humour; (iii) literary and historical ballast, ie quotes, sense of historical mission etc; (iv) good lines’. Blair was unsure, though, whether anyone would be gifted enough to provide these four things singlehandedly, remarking, ‘Unless we find a genius, one person alone won’t fulfil all these tasks’.

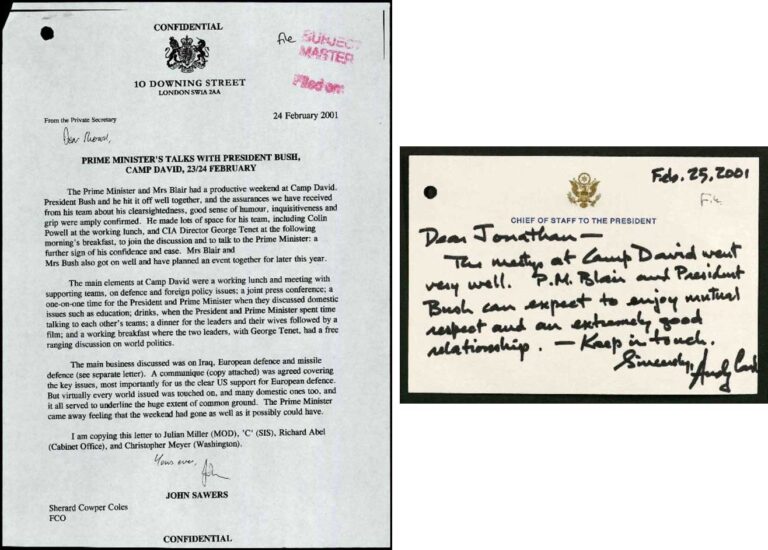

‘P.M. Blair and President Bush can expect to enjoy mutual respect and an extremely good relationship’

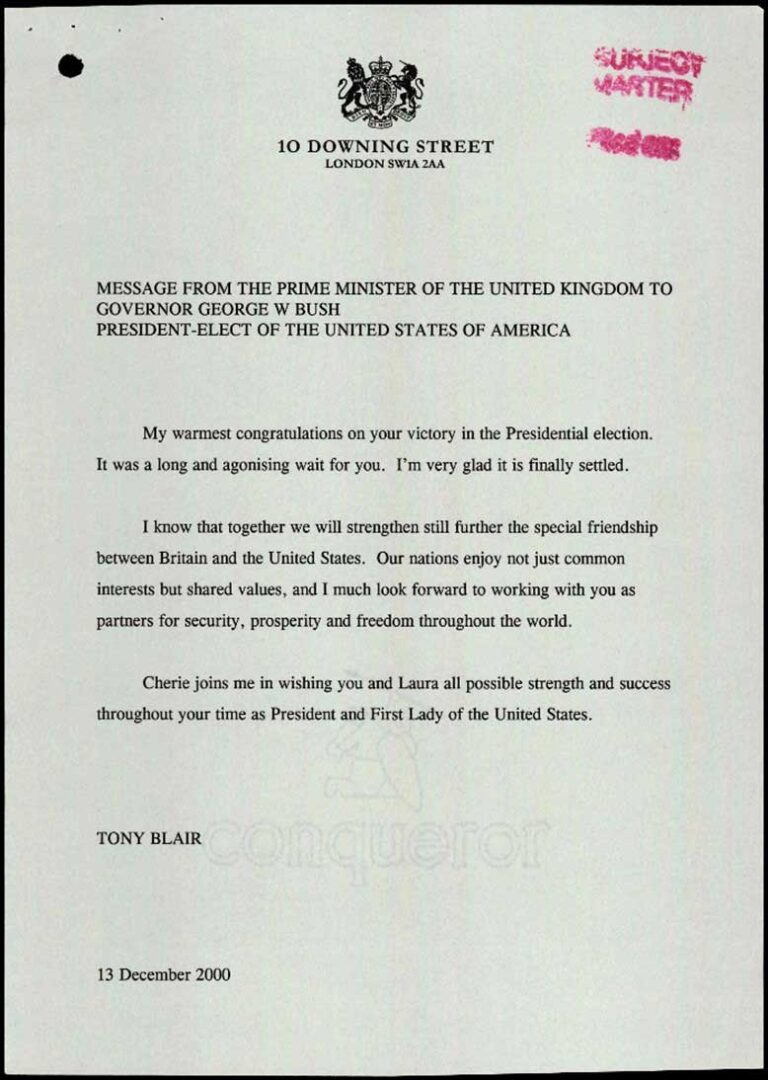

‘My warmest congratulations on your victory in the Presidential election. It was a long and agonising wait for you. I’m very glad it is finally settled’ (PREM 49/2352).

So read Tony Blair’s message to George W Bush on 13 December 2000, in the wake of his confirmation as President-Elect of the United States of America, beginning what became a close personal relationship between the two leaders, highlighted in a number of files released which relate to US/UK relations in late 2000/early 2001.

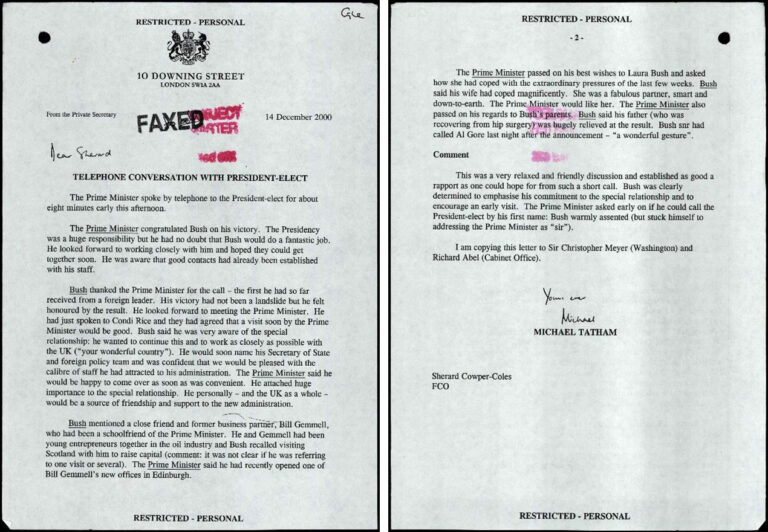

On the following day, the pair had a phone conversation – according to Bush, the first such call he had received from a foreign leader – in which they briefly touched upon the ‘special relationship’ between the UK and US, Bush’s wish to work closely with ‘your wonderful country’, and that a visit by Blair in the near future would be a good move.

Notes on the call state that ‘this was a very relaxed and friendly discussion and established as good a rapport as one could hope for from such a short call’ and that the Prime Minister had asked early on whether he could call the President-elect by his first name, to which Bush warmly assented.

The wish that the Prime Minister visit the US at an early opportunity came to fruition in late February 2001, and great efforts were made in the planning to ensure that Blair could accommodate a visit into his schedule as soon as he could, while other senior British officials held talks on a range of issues on a number of occasions with the incoming Bush Administration (PREM 49/2352).

On 23 February 2001, the Prime Minister held face-to-face talks with President Bush at Camp David, the President’s retreat in Maryland, in which it was stated that both had ‘hit it off well together’ and a range of topics were discussed (PREM 49/2354).

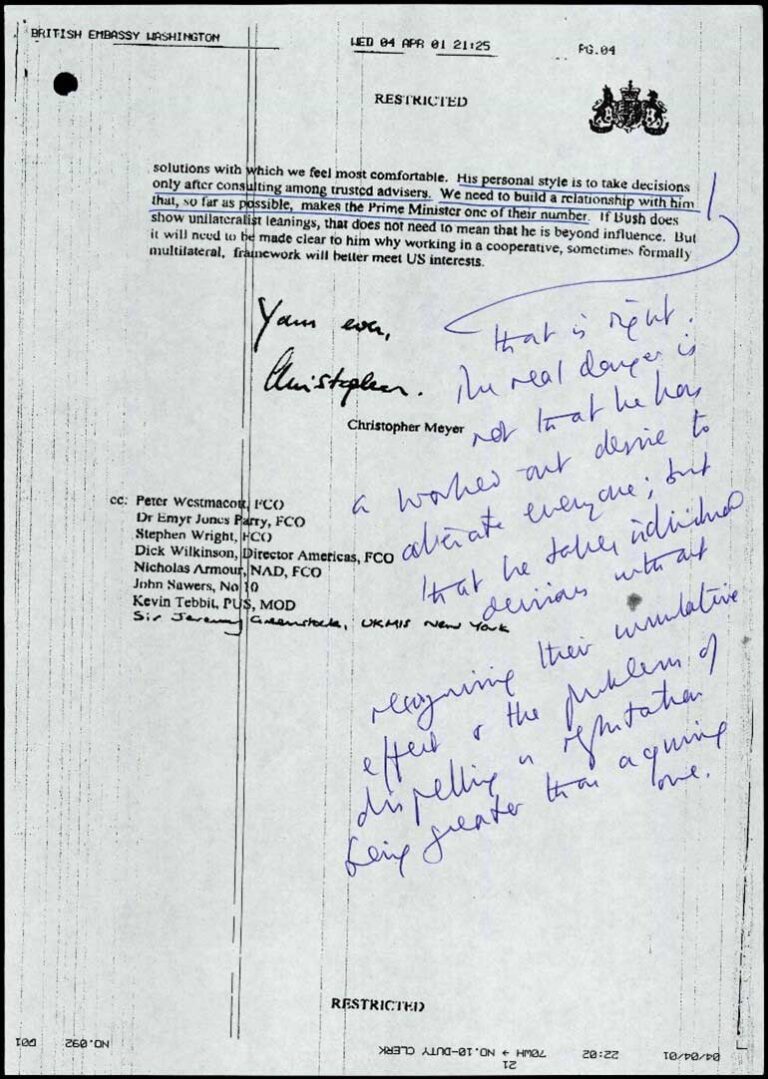

The visit was not the end of the two’s direct interaction in early 2001, as foreign policy issues continued to dominate, resulting in a telephone conversation initiated by the President in late March. The records show an attempt by British officials, quite naturally, to read the motives and decision-making process of the President and his closest advisors. In early April 2001, the British Ambassador in Washington, Sir Christopher Meyer wrote:

‘his [Bush’s] personal style is to take decisions only after consulting among trusted advisers. We need to build a relationship with him that, so far as possible, makes the Prime Minister one of their number’.

A sentiment, shown in the marginalia of the letter, unequivocally affirmed by the Prime Minister.

‘The new British informality (…) can lead to local problems’

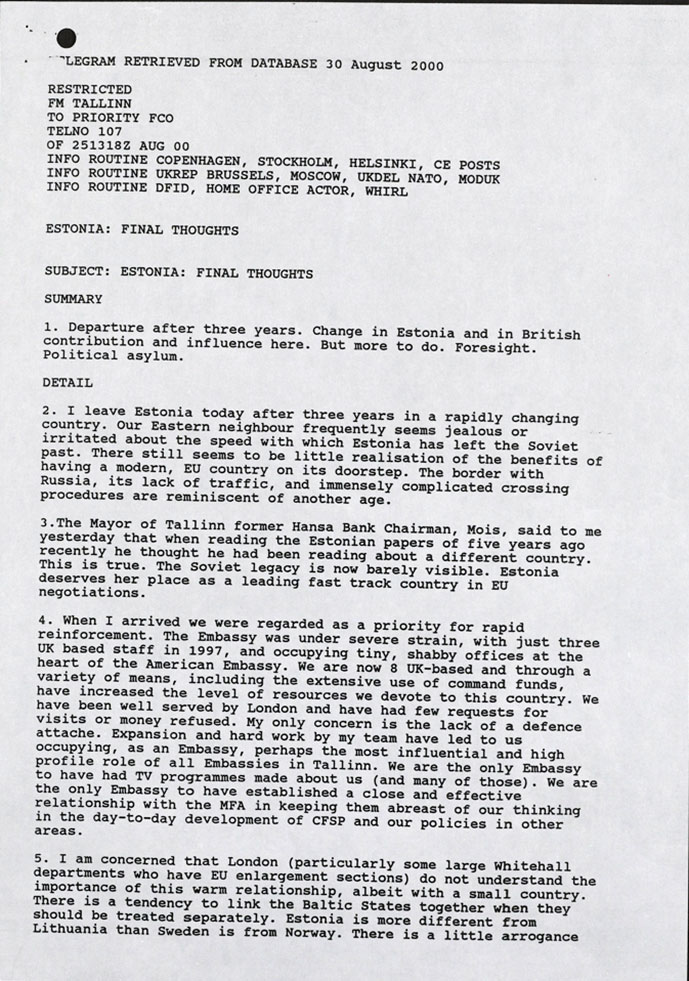

Timothy Craddock, who had just spent 3 years in Tallinn, sent a telegram entitled ‘Estonia: Final Thoughts’ on 25 August 2000, now available in file PREM 49/1737.

During his time in Estonia, he reminded the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, the British Embassy grew from three members of staff ‘occupying tiny shabby offices at the heart of the American Embassy’, to eight staff, who successfully raised the profile of the UK in the country.

He was a bit concerned by ‘the lack of a defence attaché’ and recognised they had ‘been well served by London’ in terms of funding and visits, but was nevertheless proud of the ‘hard work by [his] team’. He was leaving an Embassy with ‘high morale’, and a ‘high-tech, attractive building’, built in 1999, which had, just a month earlier, been described in an FCO briefing as ‘a showcase’ for the UK. He was convinced that ‘this post [was] at the cutting edge when it [came] to foresight philosophy’, and boasted: ‘we are the only Embassy to have had TV programmes made about us (and many of those)’.

The three years Timothy Craddock spent in Estonia were important ones for the small Baltic State. Having entered negotiations to join the EU in March 1998, it was widely considered as ‘one of the most successful transition economies’ despite ongoing income levels issues. ‘Estonia deserves her place as a leading fast track country in EU negotiations’, the ambassador said – a sentiment echoed by Sir John Goulden, the Permanent Representative to NATO.

In pure valedictory tradition, Mr Craddock also had a dig at Whitehall. He was concerned that ‘London (particularly some large Whitehall departments who have EU enlargement sections) [did] not understand the importance’ of the relationship with Estonia. ‘There is a little arrogance in Whitehall,’ he wrote, ‘and many businessmen also still say why bother’. He also stressed that they should stop looking at the Baltic States as a single entity. ‘Estonia is more different from Lithuania than Sweden from Norway’, he said, and should be considered separately.

Finally, he reminded colleagues at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office of the importance ‘to be aware of cultural differences’. He wrote:

‘The new British informality, such a change from the usual foreign image of us, can lead to local problems, not only because local nationals expect Embassies to be rather dignified institutions, but also with our crustier colleagues’.

He wasn’t a fan of dress down days even if he remained confident it wouldn’t, in Tallinn, lead to slackness. Still, standards should not be allowed to slip.

‘[Estonia] will be a dynamic, small economy worth trading with’, Craddock wrote. By the end of 2004, Estonia would have joined both the EU and NATO – and created the Skype software. Perhaps he was right about foresight!

‘It seems fine’…

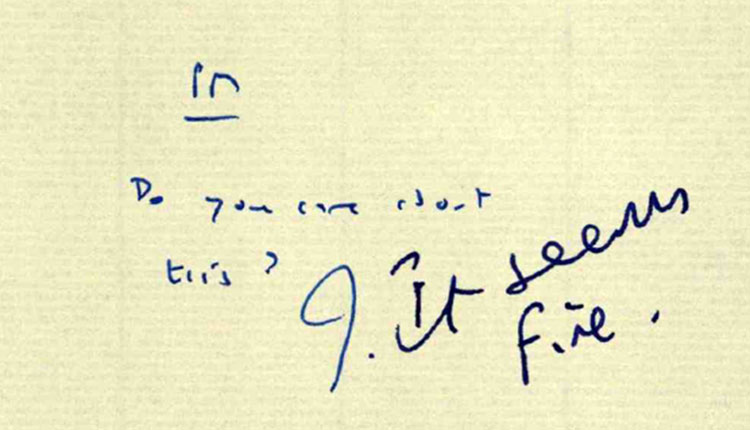

‘History will be kind to me. For I intend to write it’, Winston Churchill is said to have observed’ (see footnote 1). In the spring of 2001, though, it seems Prime Minister Tony Blair was less concerned by history, at least the official kind.

PREM 49/1991 and PREM 49/1992 concern official histories. Much of these files concern the details of compensation payments to former Far Eastern prisoners of war the Blair government authorised, and the PM and other ministers’ involvement in Holocaust Memorial Day in 2001. But the file also deals with the Government’s programme of official histories. Official histories were begun in 1908 with a military and naval focus, aiming at creating a reliable secondary source for historians prior to the transfer of documents to the Public Record Office (now The National Archives). In 1966, Harold Wilson’s government expanded the programme’s scope to peacetime matters.

In January 2001 the Cabinet Secretary, Richard Wilson, forwarded Blair a list of proposed forthcoming histories on topics ranging from the Falklands War and nuclear missiles to the Channel Tunnel and food policy. The list duly went into Blair’s red box of papers for review, although his Principal Private Secretary, Jeremy Heywood thought it might not be the top of his boss’ priorities, scribbling, ‘PM Do you care about this?’ Blair replied in the margins, ‘It seems fine’, and the past continued to be left to historians.

Footnotes

- This is almost certainly an apocryphal quote, probably based on Churchill’s observation in a 1948 Commons debate on the actions of politicians prior to the Second World War: ‘I consider that it will be found much better by all parties to leave the past to history, especially as I propose to write that history myself’. See: House of Commons Debate, 23 January 1948, vol. 446, col. 557. (Available at: https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1948/jan/23/foreign-affairs#column_557)

Really interesting, to see the document originals, and be able to read the commentary also.

Prescient commentary from Mr Craddock on the unease that Russia felt in seeing the liberisation of Estonia. 20 years on and that is undiminished. It is clear that Putin and his cronies cannot let go of the past.

I visited Latvia on two occasions in 1999 and 2001, to witness the relief that native Latvians generally experienced in shaking off the Soviet Era shackles.

Why do you not provide a direct link to the digitised CO files? I have tried using the catalogue but digitised files are not separately identified. This makes them very hard to locate. This despite several years working on records at Hanslope Park.

Due to technical difficulties, the catalogue pages linked to in this blog did not initially show the option to download the digitised files. This has now been fixed. We are sorry for any inconvenience.

Handwriting, grammar, punctuation, etc can be a fascinating subject with respect things written in haste – or otherwise.

Very interesting! Thank you.

It’s only twenty years ago, but it seems a world away. The files show how much British influence has declined over the period.

I found it very interesting and illuminating reading these extracts and no doubt the full files will be worthy of a thorough read by those interested in this period.

I would be very interested to know what % of files from beyond the 20 year rule have still to be released; typically from WW2?

My suspicion is that the public would be shocked if this number were to be revealed.