Researching the national history of a stateless people always necessitates collecting disparate documents from a wide range of archives. For the past two years I have been researching my PhD thesis on the history of the Palestinian refugee camps and the organisation responsible for them, UNRWA (the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine refugees).

In the absence of a Palestinian national archive, the relevant records are dispersed across the world, and it is left to the researcher to pull them together and examine the collective evidence. The relevant archives can be found not only in the Middle Eastern countries where the camps are located, but also in the Western states that have played such a key role in regional politics, particularly the US and UK.

The National Archives was the first collection I looked at for this project. My decision to start here was taken largely for logistical reasons; commitments kept me in London during the first few months of my PhD. I had expected to find a small amount of useful supplementary evidence in Kew, rather than anything crucial or revelatory. Initially, my fairly mundane days in the archive bore this out. I found useful but dry UNRWA records from the Agency’s early days, and letters between British and American diplomats about the political impact of the refugee crisis. The documents were informative, important, and expected.

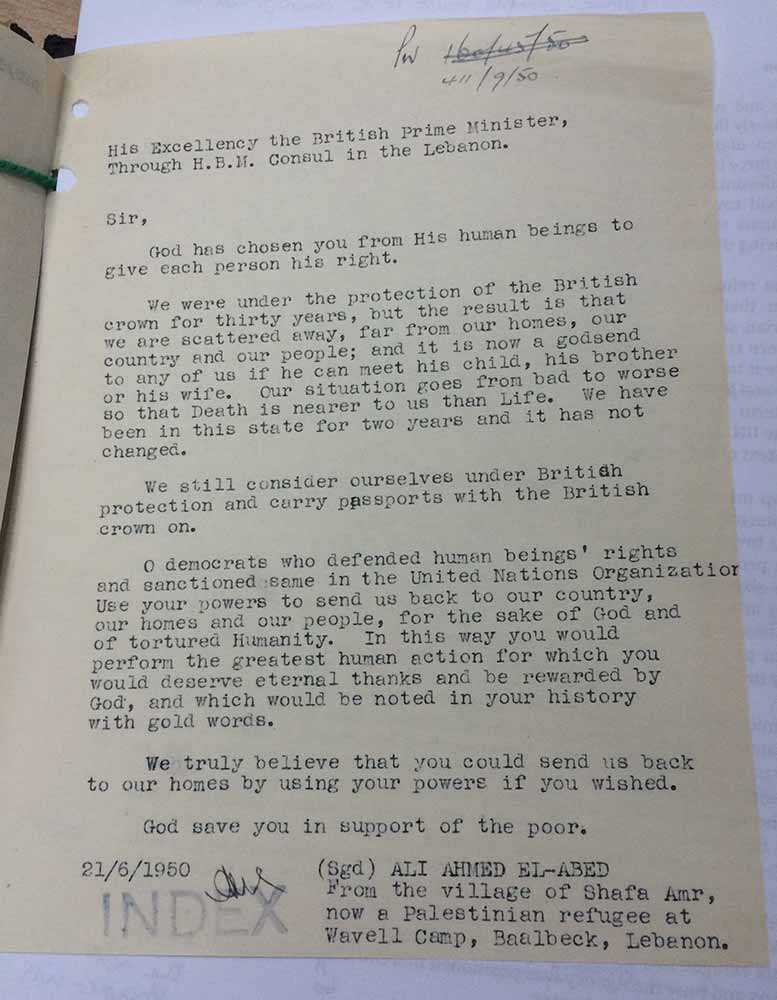

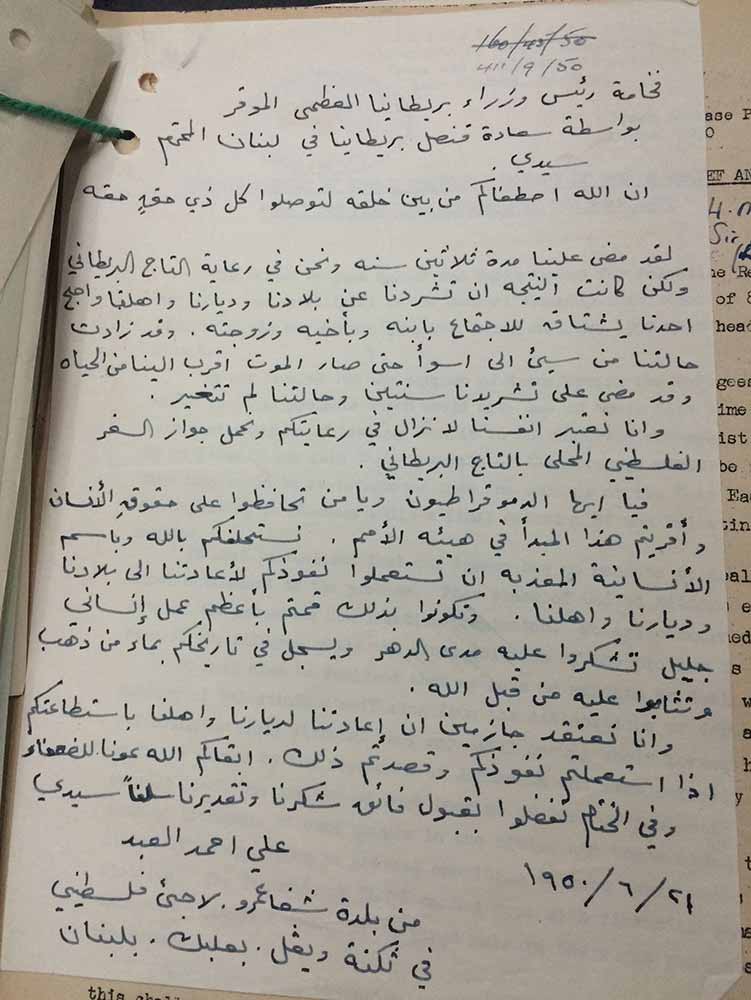

Yet among them were some unexpected gems. I was particularly struck by a letter to the Prime Minister from Ali Ahmed El-Abed, a Palestinian pleading for the UK to enforce the refugees’ right to return to Palestine. He had written:

‘We were under the protection of the British crown for thirty years, but the result is that we are scattered away, far from our homes, our country and our people… Our situation goes from bad to worse so that Death is nearer to us than Life. We still consider ourselves under British protection and carry passports with the British crown on. Use your powers to send us back to our country.’

- Ali Ahmed El-Abed’s letter to the British Prime Minister in 1950 (catalogue reference: FO 1018/73)

- The original handwritten letter from Wavel Refugee Camp in Lebanon (catalogue reference: FO 1018/73)

I had not expected to find much in the way of refugee voices in the state archives of the former Mandate power, and letters such as this added unanticipated personal notes to the dry diplomacy.

On completing my research in Kew, I judged that as expected, I had found some useful supplementary documents with relatively low-key significance. What I did not realise at that stage was the true importance of many of the documents, which only became apparent when contextualised with evidence from archives elsewhere.

Upon visiting the latter, I discovered that letters like that I found at Kew were not outliers, but in fact typical of a wider trend for Palestinian refugees to protest their plight in writing. Across archives in Jordan and Lebanon, I found similar letters to national and international authorities, alongside organised petitions. They were crucial evidence for what became a central part of my thesis; namely, the fact that the Palestinian refugees were not ignorant passive recipients of international aid, but active agents who were fully aware of their rights and very quickly organised themselves to demand them.

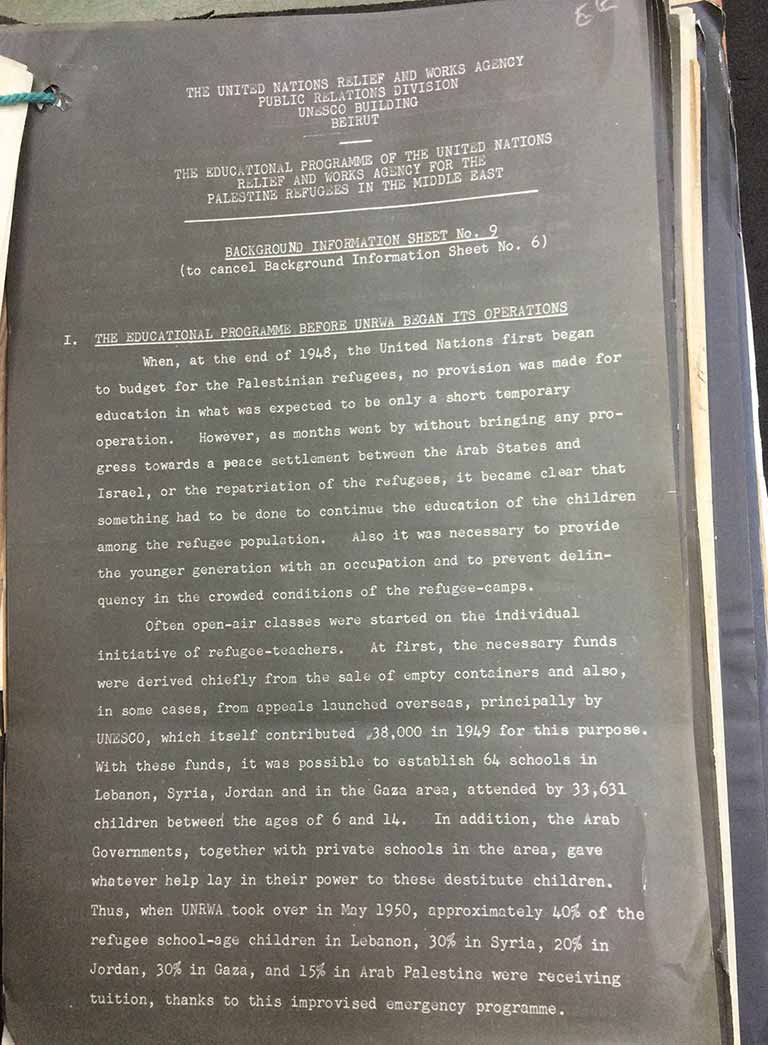

My research in the Middle East threw up even more surprises about the diplomatic documents to which I had previously given little thought. During months of research at numerous archives in Jordan and Lebanon, I was unable to track down records about the beginning of UNRWA’s schooling programme for Palestinian refugee children. The UNRWA archive in Amman contained detailed information about later decades, as did the Institute for Palestine Studies in Beirut, but the early days were drawing a blank. Returning to my notes from Kew, I was astonished and delighted to find that a key document was already in my hands. Amidst the FCO’s records about the Palestinian refugee situation was an early Information Sheet from UNRWA detailing precisely when and how the first camp schools were started.

Details about the first schools for Palestinian refugees in exile eluded me in numerous international archives, but are found here. Background Information Sheet No. 9 from the UNRWA Public Relations Division, 5 June 1952 (catalogue reference: ED 157/366)

This document provided a crucial complement to later records detailing UNRWA’s interactions with the Palestinian refugees about the schooling programme. Using the evidence from records like that in Figure 3, I was able to establish that the refugees had pushed from the beginning for a full education programme. Yet out of context the document’s significance was greatly diminished. Its increased value when combined with others exemplifies the importance of connecting collections, and the need to reconsider individual documents in the context of others in order to arrive at more nuanced and comprehensive conclusions.

Connecting Collections is a series of blogs by academic researchers, exploring the connections between archives across the UK and around the world.

What a found!

Hi! This is a fascinating piece and shows the vital importance of a unified, decolonised archive in piecing together the histories of post-imperial societies. Did you consult the FCO 141 set at all (Migrated Archives)?