During the First World War, British Intelligence made good use of scholars – notably archaeologists and orientalists. After all, as the Inspector of Antiquities at Saqqara, Cecil Firth, noted, ‘archaeologists have special opportunities of acquiring knowledge of various kinds under the pretext of scientific work.’ (FO 141/440/1) It’s therefore not surprising that German Intelligence made good use of them too.

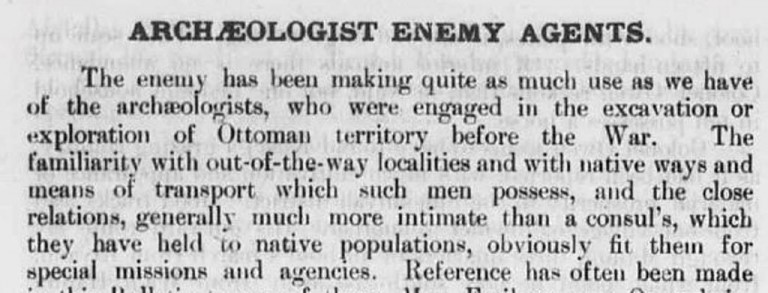

‘Archaeologists Enemy Agents’. Extract from Arab Bulletin No 92, 11 June 1918 (catalogue reference: FO 882/27)

Middle-Aged, 5 ft. 8 in. (1.725mm), slight build, blue eyes, rather prominent ears, weak looking mouth, rather receding chin, straw-coloured hair, very small moustache. Said to be fond of masquerading in native clothes.

This is how Curt Prüfer is described in his MI5 file (KV 2/3114).

Born in 1881, Prüfer completed a PhD in Philology at the University of Erlangen (now Friedrich-Alexander Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg) in 1906. His rather niche topic – the Egyptian shadow theatre – demonstrated an extraordinary grasp of Arabic. An impressive polyglot (he spoke fluent Arabic, French, English and Italian, and could get by in Turkish, Russian, Portuguese and Spanish), he was appointed as Dragoman (Interpreter) at the German consulate in Cairo in 1907.

In Cairo, he worked very closely with Max von Oppenheim, known to the British as ‘the Kaiser’s spy’. He was rapidly promoted to Oriental Secretary and used his knowledge of Arabic to build strong relationships with Egyptian nationalists and gather intelligence.

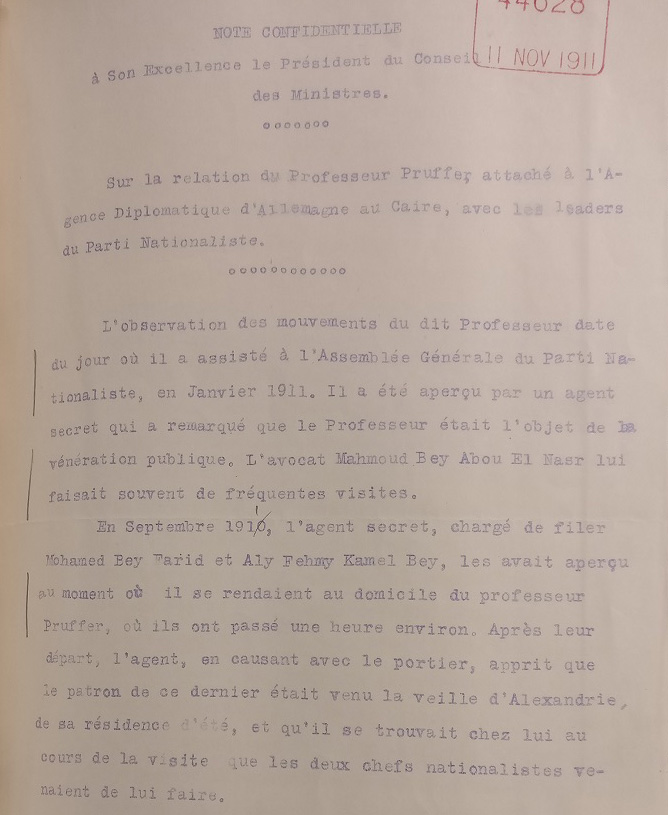

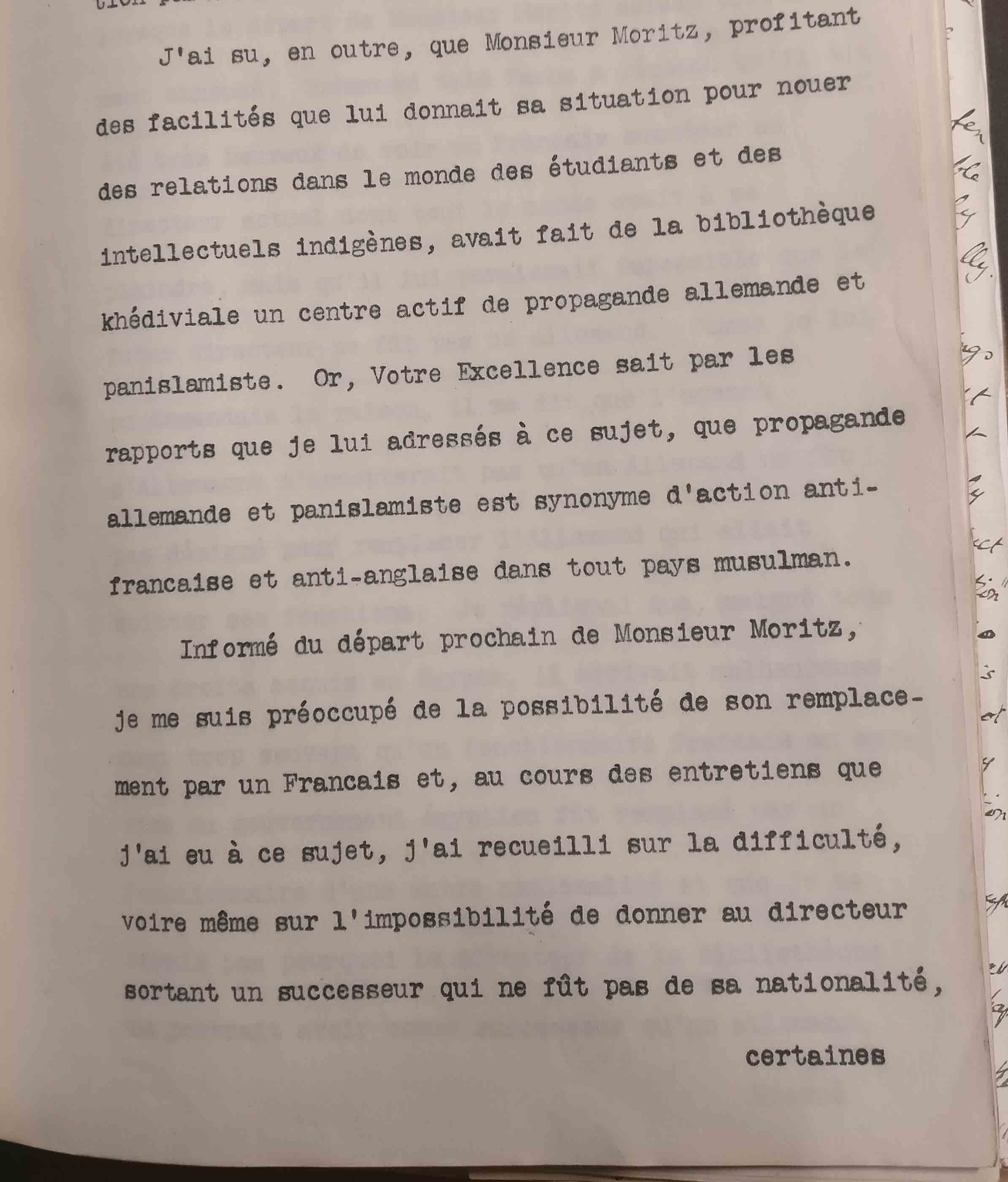

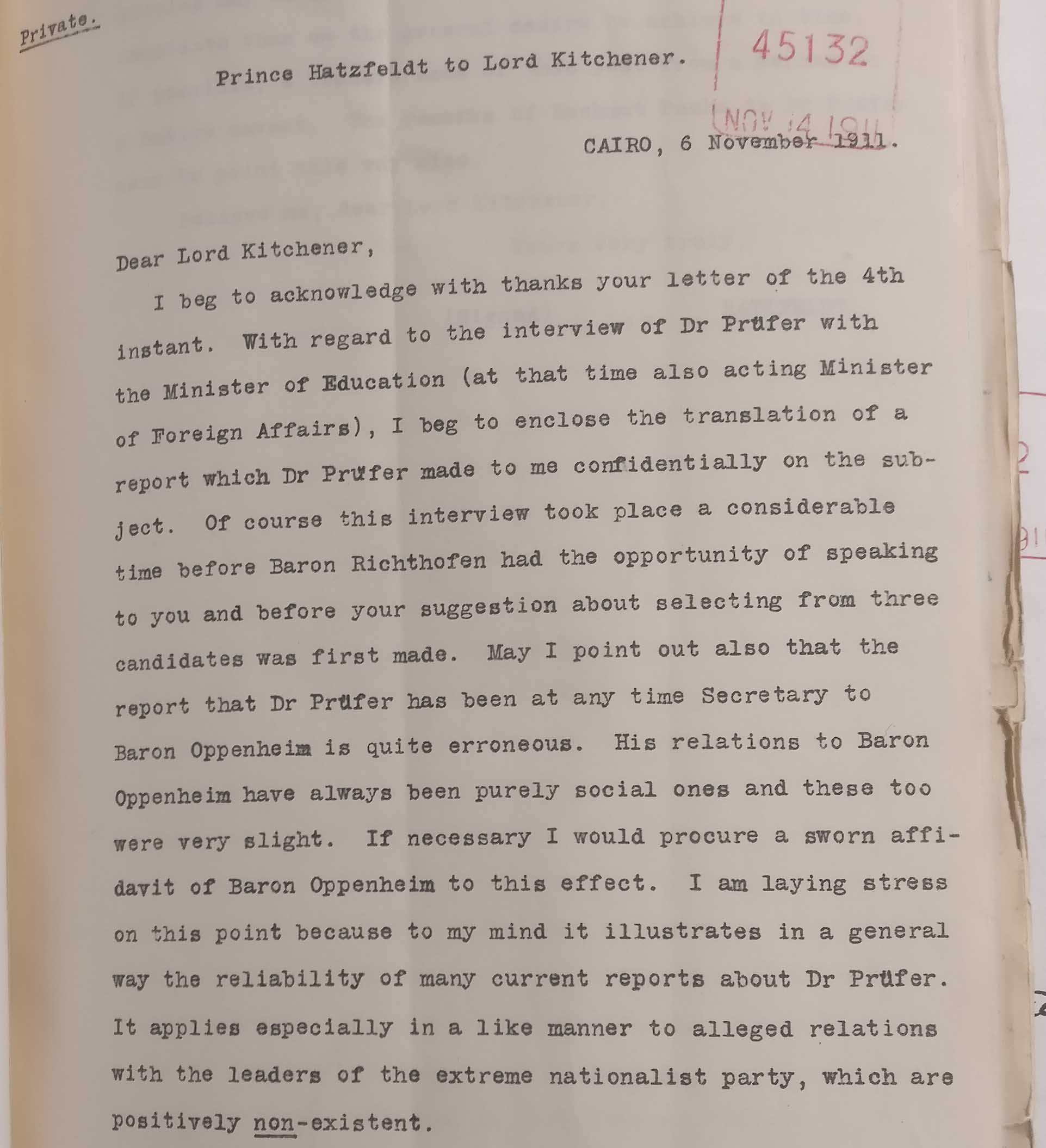

Back in 1904, it had been decided that the Director of the Khedivial Library (now the Egyptian National Library and Archives) would always be a German. Bernhard Moritz had to step down in 1911 due to ill health and continuous quarrels with the Egyptian government. He was also accused by the French Consul and Agent General of having ‘turned the Khedivial Library into an active centre of German propaganda’. The German Consul General, Hermann von Hatzfeldt, put Prüfer’s name forward to replace him. As he was one of the best German scholars in Cairo, this was hardly surprising (FO 371/1114).

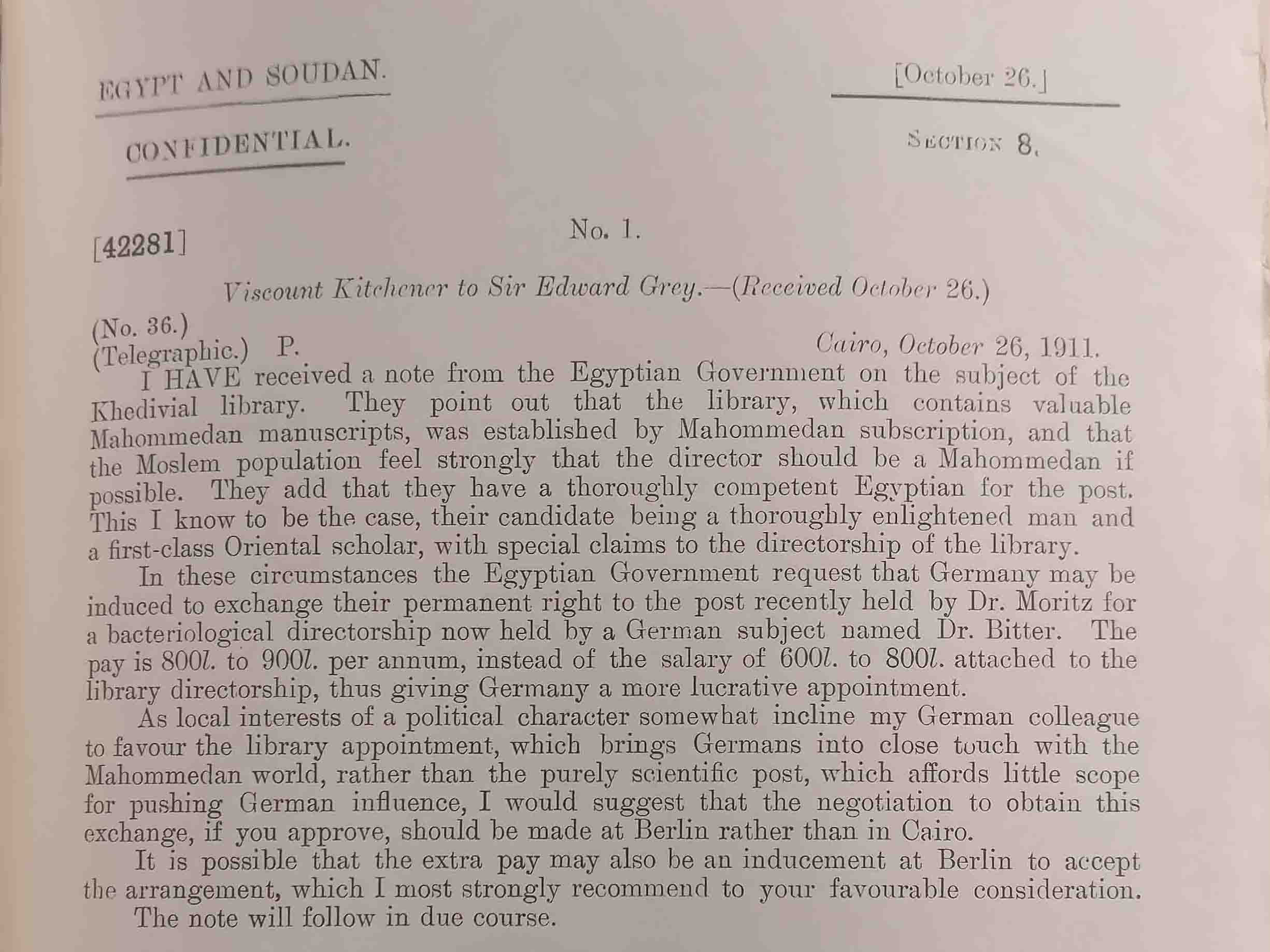

Equally unsurprisingly, the British Authorities in Egypt were staunchly opposed to Prüfer’s appointment. Milne Cheetham, the Acting Agent and Consul General, thought that ‘the nomination of a trained agent [could] only be intended for the purpose of political intrigue’. When Kitchener arrived in Egypt to take over from Cheetham, he entirely concurred. Not very impressed by the German Chargé d’Affaires’ claims that Germany would ‘guarantee Dr Prüfer as a person who would not engage in any political intrigues’, he wrote to Edward Grey:

Dr Pruefer’s activities are those of a confidential political agent, rather than those of a student of Arabic as Baron Richthofen endeavours to represent. (FO 371/1114)

At the end of October, as the German government was insisting rather heavily that Prüfer was the only candidate in the whole of Germany, the Egyptian government pointed out that, as the library contained a wealth of Islamic documents, the Director should perhaps be a Muslim. As it happened, they added, they had a suitable candidate in mind.

Kitchener then met with Hatzfeldt, and told him Prüfer wasn’t a suitable candidate because of his official position and because he was Oppenheim’s secretary (MI5 would later describe him as ‘the creature of Oppenheim’). Hatzfeldt protested in writing:

His relations to Baron Oppenheim have always been purely social ones and these too were slight. If necessary I would procure a sworn affidavit of Baron Oppenheim to this effect. (FO 371/1114)

There wasn’t much to it, the Foreign Office noted, as Oppenheim ‘had no locus standi in the Chancery’ and that his ‘duties’ were always ‘ostensibly entirely social’.

The Egyptian secret police had been monitoring nationalist leaders and witnessed visits to Prüfer. This sealed his fate and another German scholar, Arthur Schaade, was appointed in 1913. This was obviously a terrible blow to Prüfer’s academic career. At 30, he found himself with no real scholarly prospects in Cairo. Never one to give up and probably thinking, as all academics do from time to time, that there may actually be a life outside of Academia, Prüfer focused on his diplomatic work. When the war broke out in the summer of 1914, he had to leave Egypt – this was when the scholar really turned into a spy.

Confidential Note on Prüfer’s relations with the nationalist leaders, 3 November 1911 (catalogue reference: FO 371/1114)

Appointed as German Diplomatic Agent in Jerusalem, he ‘controlled an elaborate organisation for espionage and counter-espionage’. As interpreter and liaison officer between Kress von Kressenstein and Djemal Pasha, he was involved in the first Suez Offensive in January and February 1915. He was then placed at the head of the Oriental Section of the Ottoman Fourth Army where, ‘assisted by a number of Egyptian extreme Nationalists’, he used his extensive information network to try to foment an anti-British insurrection in Egypt (FO 371/7743).

He reportedly didn’t get on with Djemal Pasha, so returned to Berlin for a short while before being finding his way back to Constantinople as the Head of the German Intelligence Bureau.

After the war, Prüfer was in charge of an ‘Egyptian Commercial Bureau’ in Lausanne, Switzerland, ‘the objects of which were suspected to be political rather than commercial’ (FO 371/7743). His career flourished in the diplomatic service during the Weimar Republic: appointed Consul General at Tiflis in 1925, he became Ambassador to Abyssinia in 1927, Head of the Middle East Department of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs in 1930 and Director General of Personnel in 1936.

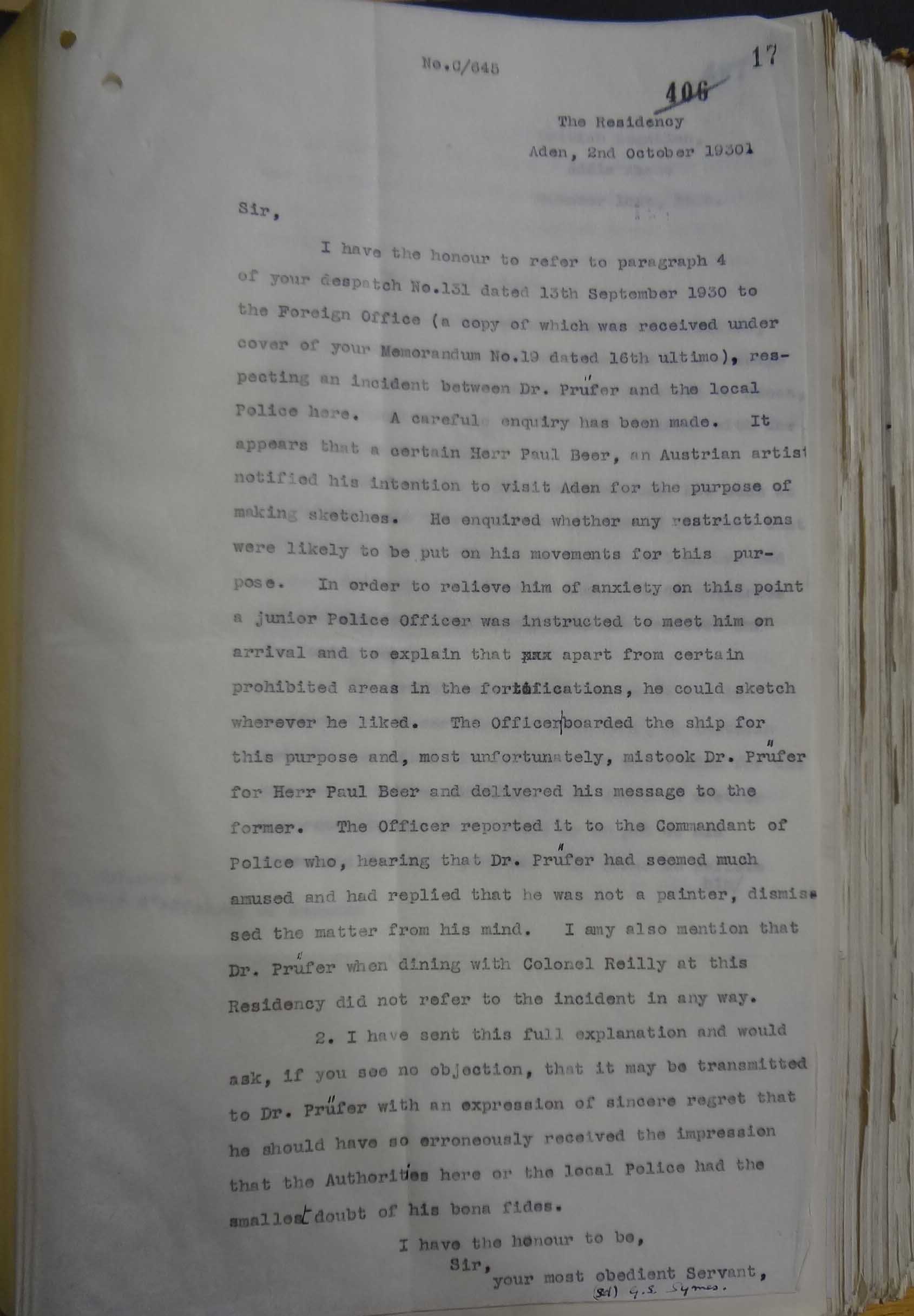

It was during his time in Abyssinia that a curious incident happened in Aden, where ‘the police apparently suspected Dr. Prüfer and his interpreter of espionage’. Old habits die hard, you might think – but it seems that, this time at least, it was all a terrible misunderstanding. Sir Stewart Symes, the British Resident, investigated and sent a detailed explanation to the Agent and Consul General in Addis.

An Austrian artist, he wrote, wanted to visit Aden and make sketches; he had asked whether his movements would be restricted and whether he could sketch anything he liked. A junior police officer was to tell him he could go wherever he wanted apart from specific areas in the fortifications. ‘The officer boarded the ship (…) and, most unfortunately, mistook Dr. Prüfer for Herr Paul Beer and delivered his message to the former.’ He reported that ‘Dr. Prüfer had seemed much amused…’ He was clearly not amused enough to prevent him suggesting he would take it up with the British Ambassador in Berlin. A bit embarrassed, Barton in Addis and Symes in Aden sent

an expression of sincere regret that he should have so erroneously received the impression that the Authorities here or the local police had the smallest doubt of his bona fides. (FO 371/14481)

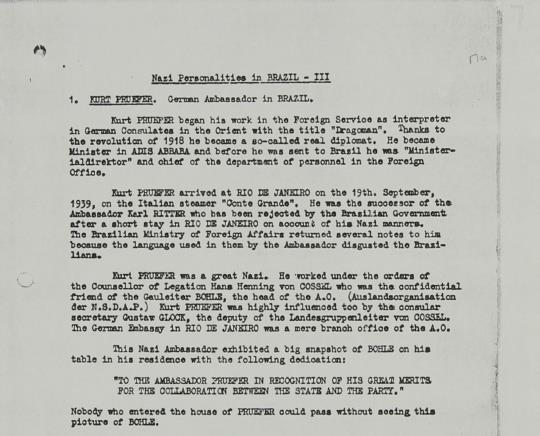

Having joined the NSDAP in 1937 (he would later be described as ‘a keen Nazi’), Prüfer was appointed Ambassador to Brazil in 1939. He arrived in Rio on 19 September 1939 and hoped to fare better than his predecessor, Karl Ritter, who had been ‘rejected by the Brazilian Government after a short stay in Rio de Janeiro on account of his Nazi manners. The Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs returned several notes to him because the language used in them by the Ambassador disgusted the Brazilians.’ (KV 2/3114)

The British Ambassador to Brazil thought that Prüfer was showing ‘more skills and circumspection’ than Ritter in his dealings with the Brazilian government, but ultimately, it didn’t work out so well. In Rio, Prüfer proved to be a somewhat poor analyst with very poor judgement indeed. In November 1941, he wrote to the German Ministry for Foreign Affairs that he was convinced the Brazilian government wanted to maintain good relations with Germany, and predicted that these good relations would be long-lasting. Brazil broke off diplomatic relations with Nazi Germany in January 1942 (GFM 33/231/235).

Prüfer then used the radio operated by the Abwehr (the German military intelligence service) in Brazil, the infamous CEL Ring, to communicate with the Foreign Ministry, sending diplomatic cables and discussing ‘drop boxes and cover addresses’. When Albrecht Gustav Engels, codename ALFREDO (KV 2/285), was arrested, he readily confessed to having met with the Ambassador regularly (KV 2/3114KV 2/3114).

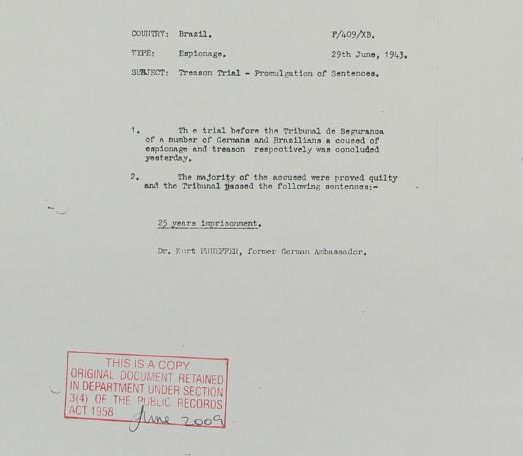

Prüfer was expelled from Brazil in September 1942, but was tried in his absence by the Security Tribunal in June 1943. Convicted of espionage, he was sentenced to 25 years’ imprisonment. In July, however, the Security Tribunal decided to cancel the sentence ‘due to the impossibility of enforcing the sentence on account of Dr Prüfer’s diplomatic immunity and repatriation’ (KV 2/3114).

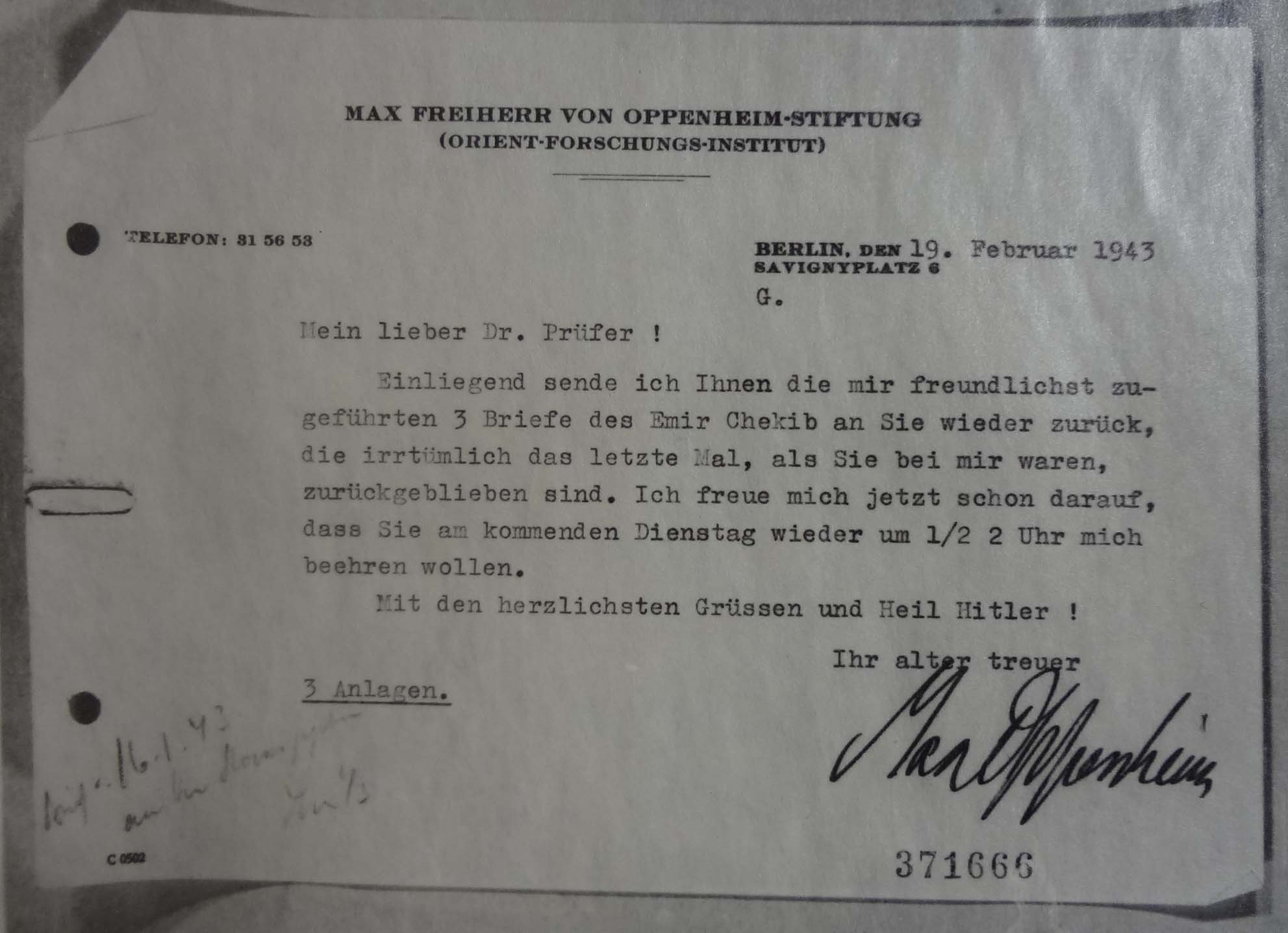

Back in the Middle East Department, Prüfer – who had kept in close touch with his old mentor, Max von Oppenheim – spent most of his time re-establishing links with his networks in the region. Oppenheim was somewhat persona non grata in Germany, being half-Jewish, but he was nonetheless very useful as a go-between and passed letters from various nationalist leaders to Prüfer.

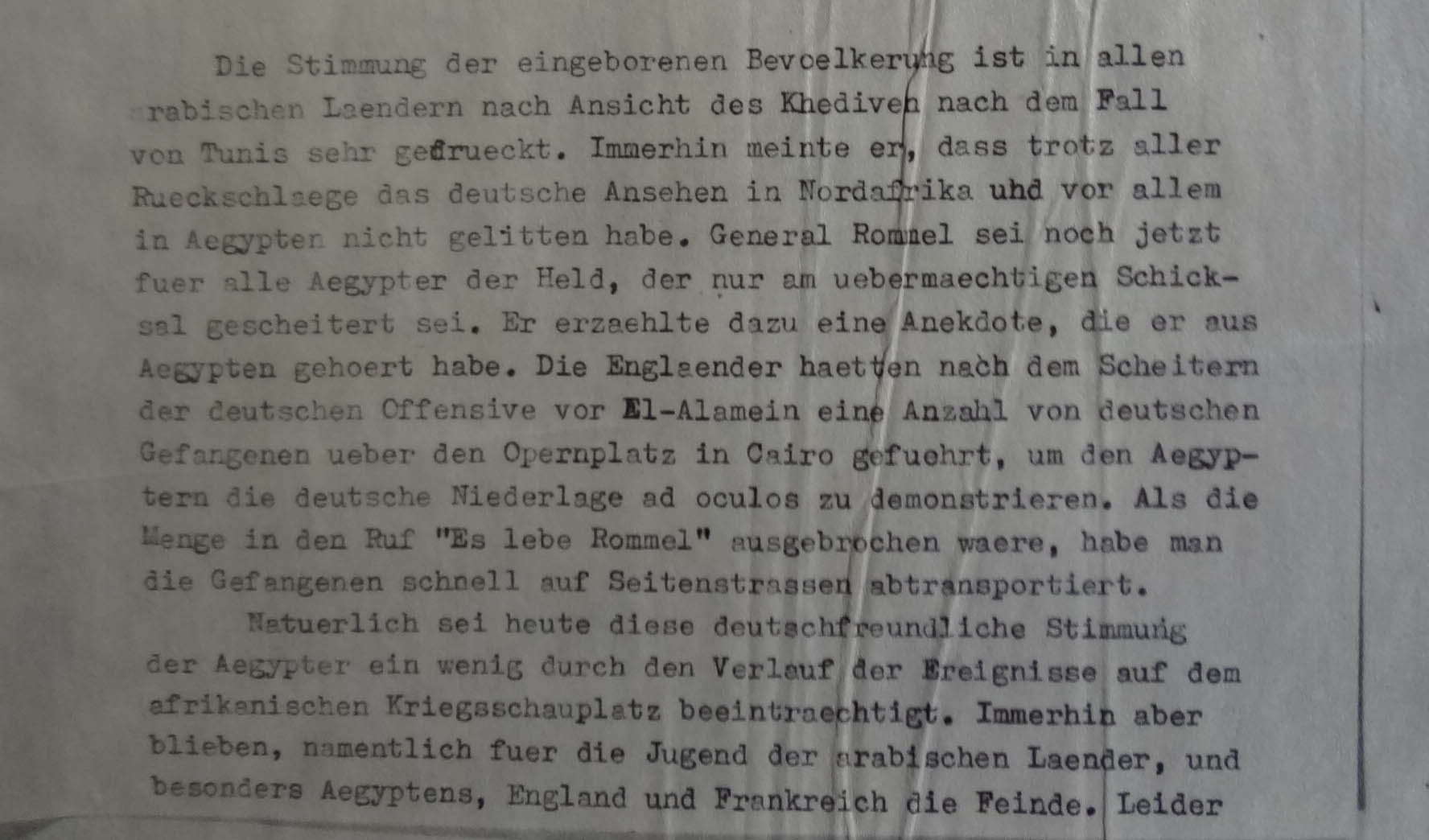

Travelling to Switzerland increasingly frequently, Prüfer also rekindled his friendship with Abbas Hilmi, the former Khedive of Egypt, who was deposed by the British in 1914. Prüfer had known him very well during the First World War, and was delighted to see that the Khedive’s anti-British feelings hadn’t diminished with old age. An ‘irreconcilable enemy of England’, Abbas Hilmi told Prüfer that, in Cairo, after the Allies’ victory at El Alamein, people started shouting ‘long live Rommel’ when they saw a column of German prisoners of war. While Prüfer recognised that this welcome sentiment was ‘somewhat impaired by the course of events in the African theatre of war’, he thought that it would still be useful to have future Arab leaders hostile to France and Britain (GFM 33/607).

Having served under three very different political regimes, and perhaps sensing the wind was turning, Prüfer finally retired in September 1943. He resurfaced in Delhi in 1948, as Professor of International Relations – much to the surprise of British officials, who thought he’d been long dead (KV 2/3114).

So, Prüfer went back to Academia in the end; it’s true that his life choices may have been determined by that first academic rejection back in 1913, but it is probably fair to say that, as James Quibell, a keeper at the Cairo Museum, put it in 1920, he was ‘a spy first and a scholar in the second place only’ (FO 141/440/1).

Fascinating details from TNA’s files.

For those interested in digging further into the story of Dr Prüfer, and indeed Frhr v Oppenheim, the last few years have seen a good deal come into print in English, e.g. Donald McKale’s “War by Revolution: Germany and Great Britain in the Middle East in the era of World War I” (Kent State UP, 2008), Lionel Gossman’s “The passion of Max von Oppenheim: archaeology and intrigue in the Middle East from Wilhelm II to Hitler” (Open Book, 2013) and Prüfer’s own papers, ed. Kevin Morrow, “Germany’s covert war in the Middle East: espionage, propaganda and diplomacy in World War I” (I B Tauris, 2016).

In “Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East ”

by Scott Anderson( 2014) one of the main protagonists is Curt Prüfer.

I recently published a scholarly edition of Prufer’s wartime writing (1914-1918) in a book titled “Germany’s Covert War in the Middle East: Espionage, Diplomacy and Propaganda in World War I.”