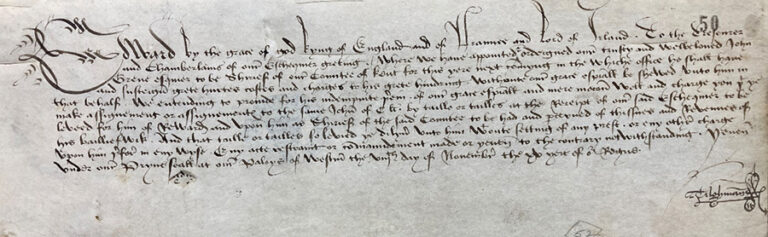

In late medieval England the monarch’s money was collected, stored and spent by officials within offices resembling modern departments of state: the Exchequer, Wardrobe or Chamber. The oldest and most complex of these, the Exchequer, managed national income and spending, acting as a strongroom for treasure, a court for financial matters, a place of audit and an archive. When kings wanted to spend large sums of money, they had to send instructions to the Exchequer as warrants written under the privy or signet seals. These are found in series E 404 between 1154 and 1837.

This cataloguing project focuses on a small part of the sequence: E 404 files for Edward IV’s reign (1461-83). Continuing work by the Richard III Society on the records for Richard’s reign (1483-85), it expands the content to the period of the Wars of the Roses. The work so far has analysed the records E 404/76/1-5 for the period March 1475 to April 1479 (the 15th to the 19th regnal years of Edward IV).

This project uses an Excel spreadsheet to collect the data from the documents, providing a streamlined method of transferring textual information into The National Archives’ catalogue, Discovery. Since each warrant is formulaic in its purpose, layout and content, we have used standard fields for dates, locations, recipients, additional people, names of clerks, and summaries of the orders. By tracking this variety of searchable data we can capture the key information that researchers need for further analysis.

Following the money trail reveals a diverse range of historical data and offers details on the administrative history of the Exchequer. This includes the appointment of sheriffs, payments to the king’s staff, suppliers of goods to the royal household, political relationships with foreign states, troop deployments and payments for war, and redistributing legal fines to reward loyalists and allies.

The warrants provide insights into how money was moved, and the identities and responsibilities of the Exchequer, Chamber and Wardrobe officers involved.

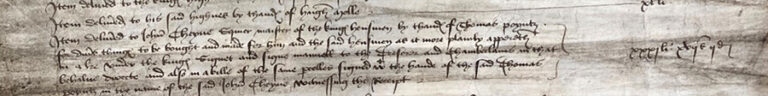

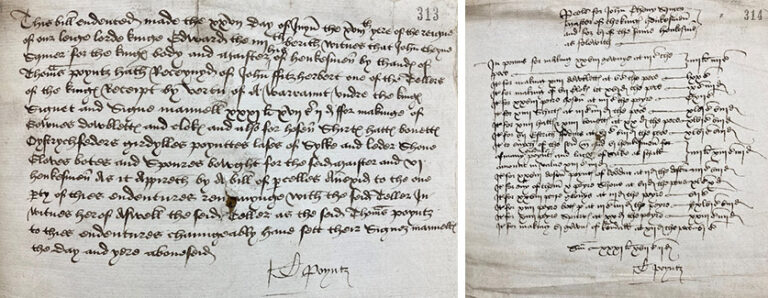

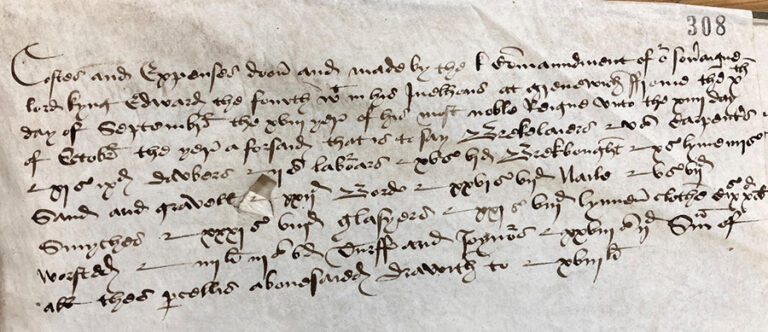

Procedural information is unveiled through references to various other parts of the system, including the records of daily spending, the books of pells and the day or journal books of the tellers (now in series E 405). Information on loans to the Crown, revenues from taxation and duties from customs taxes and the merchants engaged in trade are revealed within various orders for expenditure. Schedules for payments (itemised bills) are often attached to the warrants, breaking down how large sums were calculated and giving researchers insight into late medieval material culture.

The most prevalent types of warrant are the annual appointments of sheriffs, documenting appointment dates and the reimbursement of costs (since they served without salary). These documents occasionally list previous office holders and highlight the process of striking wooden tallies by which the payments were often registered and made (see E 404/76/1/, no. 52 above).

The warrants provide information regarding the king’s household staff, documenting the grooms and pages of the king’s and queen’s chambers, the esquires and knights assigned to serve the king, the king’s medical officers, and clerks and secretaries. Certain individuals are frequently mentioned, such as the clerk of the king’s jewel house, William Daubeney, who was responsible for maintaining, distributing and transporting jewels and precious items. His skill as a craftsman is also apparent, as he gathered raw materials to create items at the king’s request. The career trajectory of another close ally, John Cheyne, is revealed in warrants showing his service in 1475 as an esquire for the king’s body and master of his horse. He then moved to the role of standard-bearer in 1477, and became the master of the king’s henchmen, or riding bodyguard, by 1479.

The warrants provide information regarding the design of clothing and furnishings. Some describe in detail the fabrics, embroidery and style of the cloth issued to the king’s household people. Many of the auxiliary documents referenced in the warrants are lost or separated in other series held at The National Archives, but some striking examples do survive. A sequence linked to the outfitting of the king’s henchmen includes the bill written by the craftsman responsible for the work itself.

During 1478-79, Edward IV redecorated his personal chambers. A series of warrants describe the green and white, gold, black and blue fabrics, and reveal adornments such as arras tapestries, including one depicting the story of Noah. These deepen our impression of the king’s choices and favour given to London artisans.

Other warrants recorded payments for purchases of land and construction or works at royal buildings, from hunting lodges in Essex to extensive works on Nottingham Castle. A bill describing the employees, supplies and works on Greenwich Palace survives (E 404/76/4, no. 133).

The warrants supplement work on diplomatic history. Several calculate the travel expenses of English ambassadors and the cost of presents for visiting dignitaries. There are sometimes gifts for births, marriages or deaths. Schedules highlight the increase in gift giving and ambassadorial vests during major feast periods such as that from Christmas to Twelfth Night (E 404/76/4, no. 136).

One document reveals how international peace treaties could be referenced in resolving problems. A ship destined for the port of London, the Jacob of Hamburg, ran aground on the coast of County Durham during a storm. Although it was intact, Thomas, Lord Lumley and his men raided the vessel, stealing a large part of the cargo. An accord between England and the German states in the Holy Roman Empire is referenced as justification for speedy restitution of the value of goods for the merchants affected by these actions (E 404/76/4, no. 34).

Many warrants highlight forfeitures of bonds for keeping the peace and the methods used to redistribute the fines that arose. Those who stood surety to guarantee the behaviour of the main people bound did so under a potential fine if the bonds were broken. For example, John Smith of Arkesden, Essex, repeated his offence and activated his suspended fine of £20. His three sureties each forfeited their pledge of £10. All fines were assigned as a reward to four of the grooms of the king’s chamber (E 404/76/5, no. 2).

Many of the best details of military preparations and costs come from Exchequer warrants. We can find descriptions of troop deployments, their periods of service, and daily wages. These make an important contribution to calculating the cost of defending England’s frontiers, and identify some of the people on whom the king relied to keep his territories secure. Two warrants describe how money was transported from London to Calais as wages for the garrison there. The money was carried by an officer of the Exchequer, accompanied by two of the king’s councillors and guarded by eight other men (E 404/76/4, no. 112), to be handed to the controller of Calais for distribution (E 404/76/4, no. 113).

Together, these documents provide a wide lens through which we can view Yorkist England towards the end of the 15th century. They reveal how the royal family collected and distributed money, maintaining the lifestyle that their subjects expected. The documents illuminate the state of a country still dealing with the effects of civil war, capturing historical moments from progression in the king’s service to building works, criminal activity, embassies and military preparations. They show government at work, revealing the mechanics of the machinery that placed medieval kings at the heart of the financial business that kept them in power.

Very interesting and informative.!

English history has always gave me pleasure and enlightenment.

Regards,

Bob Marshall.

Fascinating. Gives a truer picture of the times than all the endless gossip about the Tudors that seems to pass for history these days.

INFURIATING ;]

please stop teasing PLEASE give us the names

‘There are sometimes gifts for births, marriages or deaths.’

‘the bill written by the craftsman responsible for the work itself.’

or at least a link to any full transcription if and when its published

many thanks

Yorkist historian Dr Betram Wolffe would have been so pleased that these documents are being catalogued.

It’s also wonderful for us historical novelists fascinated by this era.

Well done, N A!

Yorkist historian Dr Betram Wolffe would have been so pleased that these documents are being catalogued.

It’s also wonderful for us historical novelists fascinated by this era.

Well done, N A!

My keen interest iin history started with the Tudors. I realise l have been missing out on a great part of history. Thank you.

I look forward to the historical fiction yet to be created!