When looking at British history in the twentieth century strong Anglo-American ties appear to be something you can take for granted. Iconic images of Thatcher and Reagan standing shoulder to shoulder pad, or Churchill and Roosevelt sharing a joke have come to symbolise something described simply as ‘the special relationship’. If, however, we wind the clock back 100 years the picture looks rather different.

Recently at The National Archives we have completed a project to digitise the FO 1111 card index. These cards provide the best way to find something within our treasure trove of Foreign Office correspondence between 1906 and 1920. These index cards have now been made available to download for free from our website. Whilst going through some of these cards one entry caught my eye. It was discussing a plan to celebrate the Anglo-American Peace Centenary in 1914. The intention was to commemorate the remarkable fact that Britain and America had managed to avoid going to war with each other for the preceding 100 years.

Having had my interest piqued I decided to order up the original file and see what was going on. The documents reveal much about the state of relations between Britain and the USA. The intention was to celebrate the passing of 100 years of peace since the signing of the Treaty of Ghent on Christmas Eve 1814. The initial plans came from the British-American Peace Centenary Committee, a group of private individuals who felt that it was important to strengthen Anglo-American relations. So far so good. The issues came when the committee asked both governments for financial support. The British, not wanting to appear too keen, resolved to do nothing unless the Americans took the lead. As such all eyes were focused on the House of Representatives, which debated a bill on whether or not to provide funds for a centenary celebration. Colville Barclay, the British Counsellor at the British Embassy in Washington, reported the events to the Foreign Office. He wrote that things began badly when the Republican Leader of the House spoke against the bill, but worse was to come:

‘Mr Gallagher, representative from Illinois, followed in a more violent strain. He said that England was only at peace when it was to her advantage. The passage of the Bill would be a sham and a glaring lie. One hundred years ago British invaders, under General Ross with a force of 4,000 men, appeared in the Potomac, captured Washington, and before evacuating the city burned the Capitol and the public buildings to the ground. Few more shameful acts were recorded in civilised history, and it was the more disgustingly shameful in the fact that this atrocious act of vandalism was done under strict orders issued from the Government in England. In the Civil War England attempted to form a European coalition against the Union. In the Spanish-American War her diplomacy exerted her agencies against the United States. Whenever she had the opportunity her secret intrigues and machinations had been directed to the same end.’ (31805/881/45, Barclay to Grey 2 July 1914, FO 371/2151)

Mr Gallagher’s views may have been extreme, but they were clearly reflected by other members as the bill was soundly defeated. Indeed British representatives in the United States began reporting that the planned celebrations were tending to stoke anti-British feeling rather than building bridges.

The strength of animosity displayed surprised me, and I decided to see if the feelings were reciprocated. In the end I had to look no further than the Annual Report produced by the British Ambassador Sir Cecil Spring-Rice. In it he declared that:

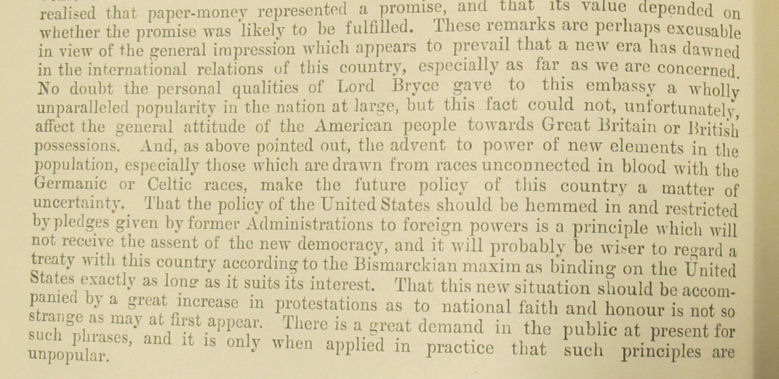

‘It is customary at international banquets to talk of the common lineage and the common inheritance of Great Britain and the United States. These remarks, which are greeted at the moment with enthusiasm, are generally followed by statements in the press based upon inexorable facts, to the effect that about one-half of the people of the United States have absolutely no race connection with England and those who have have a strong hereditary reason for wishing ill to their ancient oppressor’ (26749/26749/45, ‘United States Annual Report 1913’ sent by Spring-Rice 1 June 1914, FO 371/2155)

Spring-Rice went on to attack the new American President, Woodrow Wilson. The British Ambassador concluded that ‘It is doubtful whether any sovereign in the world rules his people so autocratically as President Wilson’. This is all a very long way from the ‘special relationship’ and the common view of the Anglo-American connection being a bastion of liberal democracy.

In the end the issue of the peace centenary was entirely overshadowed by the outbreak of war in Europe in the summer of 1914. It was felt that celebrations of peace at such a time were inappropriate and the programme was limited to a few low key events in the United States. In fact the early part of the First World War saw Anglo-American relations strained to breaking point over the implementation of the blockade of Germany.

With the perspective of a century it is easy to assume that the strong language and cultural connections between Britain and American have always ensured a special relationship. As my chance find in the Foreign Office index reveals, this was not the case. As late as 1914 the relationship was fraught and it was only the shared experience of the First and in particular the Second World Wars that cemented the connection between the countries. It also highlights the amount of fascinating information that remains hidden in our archives and can be brought to light with the help of indexes such as the FO 1111 card index.

I don’t disagree about the hidden archives, however I disagree about the ‘Special Relationship’, even in the 1960s the Foreign Office when asked about it stated that there was no such thing (see the files at TNA!) and history (Suez, Falklands, Grenada, Northern Ireland, the economic crisis in the 1960s, Vietnam) show that the ‘Special Relationship’ did not benefit the UK . The Americans decided (in my view correctly) not to give financial support to the UK during the Suez operation and there were two options, either to stay and Sterling would continue to fall at an alarming rate or get out.

The relationship is almost raised every time a new Prime Minister or President is appointed. The 1914 papers are almost unbelievable as the Foreign Office is normally defensive and the British Government did burn the White House down in 1814 (you may recall the problems about the cake recently about this lead to diplomatic issues this year, does that mean we should have a new treaty next year to celebrate defeating Napoleon at Waterloo?.

When Churchill and Roosevelt met during the Second World War it was it is said Churchill was taken aback when Roosevelt said the Allies wanted total surrender by the Nazis without realising what it meant and Churchill said that he was the President’s ‘ardent lieutenant’.