On 11 November 1965, Southern Rhodesia’s prime minister, Ian Smith, unilaterally declared his territory’s independence from Britain. Not since the United States in 1776 had a British colony declared itself independent, and the Rhodesian declaration was not dissimilar in language and syntax to its American forerunner. That afternoon Smith addressed the nation. He assured them that Rhodesians remained ‘second to none in our loyalty to the Queen’, but ‘the end of the road has been reached’.

The road to Southern Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) began at the Victoria Falls conference in the summer of 1963. It was here that the dissolution of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, or Central African Federation (CAF), was agreed. Two of Federation’s constituent members, Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia, became independent in 1964 as Malawi and Zambia respectively. Southern Rhodesia was more problematic. Unlike its former partners, which were British protectorates, Southern Rhodesia had been a self-governing colony since 1923. However, it was also dominated by a white minority numbering 224,000 according to the 1965 census, as opposed to over 4 million Africans. Predominantly British in origin, this minority community was strong and largely united. It also had the support of the ‘Rhodesia lobby’ on the Conservative backbenches back in Britain.

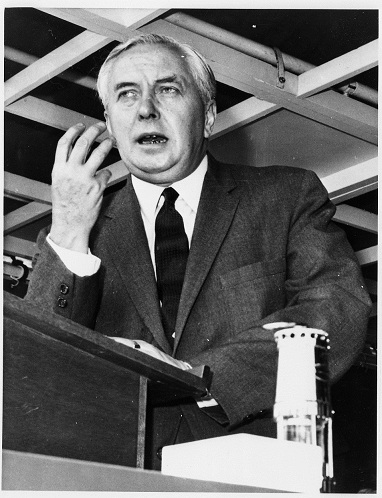

Harold Wilson, prime minister 1964-70 and 1974-6 (catalogue reference: COAL 80/1119/37)

Winston Field, Southern Rhodesia’s prime minister at the dissolution of the CAF, sought independence on the basis of the 1961 constitution. The key problem with this solution lay with the franchise. Voting provisions were complicated, with two voting rolls. Race was not mentioned in terms of allocating a person to a roll, but the property, income and education qualifications for the ‘A’ roll ensured that it was predominantly European, resulting in the dominance of the white minority. The Conservative government of Alec Douglas-Home was therefore unwilling to grant independence on the basis of the existing arrangements. Aside from the moral and ethical imperative of ensuring fairer representation for the majority black African population, Britain also came under international pressure. Fellow members of the United Nations and especially the Commonwealth opposed any solution that facilitated continued minority dominance, and appearing to support the Southern Rhodesian government risked serious damage to Britain’s international reputation.

With progress towards independence slow, Smith replaced Field as Southern Rhodesian prime minister in April 1964. A forceful character, Smith was even described in September 1964 by Southern Rhodesia’s High Commissioner in London, Evan Campbell, as a ‘stubborn old pig’ (PREM 11/5039). Given the political complexities and facing an election in October, Douglas-Home aimed to prevent Rhodesia from declaring independence unilaterally, while also pursuing a policy of delay. As Cabinet Secretary Burke Trend minuted in June, that ‘I take it that our objective is to try to play this issue as long as possible’ (PREM 11/5048).

The British general election of October 1964 resulted in a narrow victory for Harold Wilson’s Labour Party. The change of government was not warmly received in Salisbury. The Southern Rhodesian government had long feared that the party would be less than sympathetic to their position. Back in February, Campbell expressed his fear that Labour would ‘throw Southern Rhodesia to the United Nations wolves’ (PREM 11/5047). Shortly after taking office Wilson demanded an assurance from Smith that he would not declare UDI. When no reply was received, Wilson released a statement outlining the implications of a UDI.

Attitudes hardened over the summer of 1965. The Rhodesian general election in May 1965 resulted in a landslide for Smith’s Rhodesia Front party, which won all 50 ‘A’ roll seats (there were only 15 seats for ‘B’ roll voters). The same month British policy was encapsulated in five principles for a settlement, with an emphasis on progress towards majority rule. Commonwealth prime ministers met – without Smith – in London in June 1965. The resulting communique also emphasised that any settlement must include provision towards majority rule. By the time Smith visited London in October 1965, both sides were entrenched in their views. Wilson decided to visit Rhodesia later that month, but was unable to secure Smith’s agreement to creating a royal commission to consider the terms of independence.

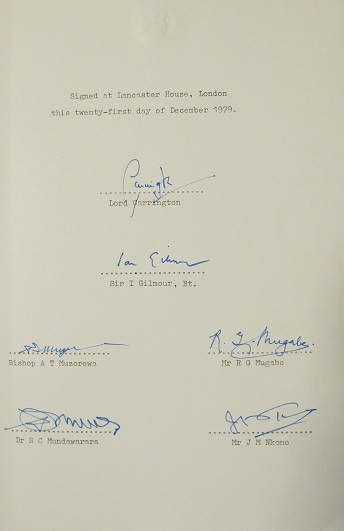

Signatories to the Lancaster House agreement (catalogue reference: FCO 36/2444)

The long-feared UDI eventually came on Armistice Day. In response, Ndabaningi Sithole and Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) and the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) under Joseph Nkomo both declared breakaway governments. Back in London, The Wilson government preferred the term ‘illegal declaration of independence’, or ‘i.d.i.’. It ruled out military action and was also keen to ensure that no such action was taken under UN auspices (CAB 128/39/76). Instead, Britain sought the imposition of sanctions. While the UN approved the suggested measures, they failed to end the ‘rebellion’. Other states, most notably South Africa and Portugal, continued to trade with Rhodesia. The oil embargo was delayed until Christmas.

In the mean time, the Rhodesian Bush War intensified. This pitted the well-armed Rhodesian security forces, supported by South Africa, against the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA), the armed wing of ZANU, and the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA), which was linked to ZAPU. There were ongoing attempts at a settlement. In December 1966, Wilson and Smith famously met off the coast of Gibraltar aboard HMS Tiger, with another round of talks taking place in October 1968 aboard HMS Fearless. Rhodesia’s leaders, however, continued to distance themselves from Britain. Withdrawal from the Commonwealth came in December 1966. In 1970, Rhodesia declared itself a Republic. It was not until 1979 that the future of Rhodesia was settled, where agreement at the Lancaster House conference finally paving the way for majority rule in what became Zimbabwe.

Although economic sanctions were imposed (see the files , for example in T 231 and other Treasury files) they were widely flouted and ineffective. Portugal itself had its ‘colonies’ in Africa until the mid-1970s so the fact that they traded with Rhodesia should not come as a surprise. As far as Britain was concerned Rhodesia had tobacco which the UK would want whereas South Africa had gold and which was must more important.

[…] On 11 November 1965, Southern Rhodesia’s prime minister, Ian Smith, unilaterally declared his territory’s independence from Britain. Not since the United States in 1776 had a British colony declared itself… Go to Source […]

thanx for yor help

I am looking for community and youth development information during this period for Southern Rhodesia. Can I have an insight where i can find that or is there anyone on this platform who can help?

Hi Honest,

Thank you for your comment.

We’re unable to help with research requests on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

I hope that helps.

Nell

Information on the evolution of community development and the growth of growth points.

Zapu leader in 1965 was Joshua Nkomo not Joseph Nkomo

Nice simple notes mostly appreciated

PLEASE NOTE: Due to the age of this blog, no new comments will be published on it. To ask questions relating to family history or historical research, please use our live chat or online form. We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.