Content note: This blog contains an image of children dead or dying due to famine that some people may find upsetting.

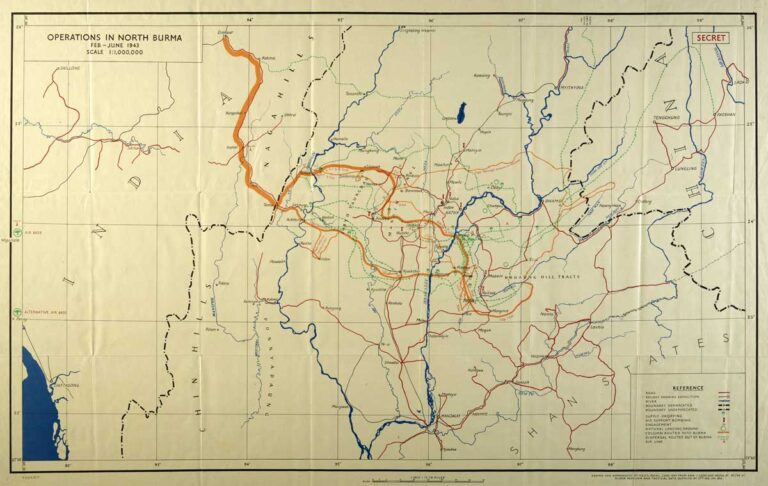

The Chindits, officially called Long Range Penetration Groups, were special forces engaged in irregular warfare against the Japanese in occupied Burma (current day Myanmar) during the Second World War. This blog looks at some of the most famous and controversial aspects of Operation Longcloth (February to June 1943), the Chindits’ first campaign, as related in the war diaries of the 13 King’s Regiment (Liverpool), which are held at The National Archives.

Operation Longcloth

The immediate context for Operation Longcloth was the fall of Burma to the Japanese in March 1942, forcing a 1,000-mile retreat of British forces to India. Soon after, on 8 August 1942, the All-India Congress Committee launched the Quit India movement. Both events encouraged a sense that Britain’s grip on its Empire was loosening, subject to assault from without and rebellion from within. In the Japanese, the Allies were perceived to be facing an inhuman enemy, as Katherine Howells has described in her blog on British WW2 anti-Japanese propaganda.

A major objective of the operation was to restore confidence in British troops that the seemingly invincible Japanese could be successfully combatted. A secondary aim was to test whether the Burmese, in particular ‘tribesmen’ living in hill areas, could be incited to revolt against foreign occupation. This ‘hearts and minds’ counterinsurgency strategy was redeployed by the British in South East Asia during the Malayan ‘Emergency’ (1948-1960), the subject of this previous blog.

The Chindits were a multi-ethnic brigade, comprised of British, Burmese, Nepalese, Indian and, in later operations, African soldiers. But they were part of the Special Operations Executive rather than the ‘forgotten’ Fourteenth Army of Commonwealth troops, who fought in Burma in 1944–45.

Far from being forgotten, there are numerous recalled and imagined accounts of their unorthodox methods. Eight columns of roughly 300 men and 120 mules, coordinated by wireless communications and supplied by air drops, were to penetrate behind enemy lines and disable Japanese communications. Each column was to be ‘large enough to deliver a heavy blow, but small enough to evade the enemy in case of need’.[ref]’Notes on the functions of long range penetration groups and summary of a report on the operations of 77 Indian Infantry Brigade in Burma, February to June, 1943′ (1943). Catalogue reference: WO 231/12[/ref]

The details in these diaries counter idealised accounts of Operation Longcloth as involving a seamless coordination between men, machines and animals, ground and air forces, allowing for a smooth incursion into the jungle. Press cuttings included in these records reveal how state-sanctioned narratives of British wartime policy were promoted, but they also point to how they were contested.

By land, water and air

On the morning of 20 April 1943, a junk boat could be seen recrossing the Irrawaddy River in Burma.[ref]Description of the river crossing and jungle airlift are from WO 172/2516, the Burma 1943 war diary for the 13 King’s Regiment (Liverpool) (1943). This records the movements of the various columns in the Northern Group of the Chindits: 3,4,5,7,8 and Brigade headquarters.[/ref] These distinctive square-sailed vessels were first used in ancient China but had been plying South and South East Asian waters since the Middle Ages. The boat was conveying a group of Chindits and a mule. Non-swimmers sat inside, whilst the swimmers clung onto the vessel and the mule swam alongside – like the elements in a real-life river-crossing puzzle.

The men were returning to India from a foray into Japanese-held Burmese territory. The mule was the sole survivor in its pack, the other transport animals having been abandoned or eaten. It was carrying a wireless radio transmitter, the only means to communicate with the British army airbase in Agartala, North East India, and Brigade leader Orde Wingate. Four soldiers were assigned to its care and feeding to allow for the performance of this important job.

The junk had been commandeered from locals. Army-supplied dinghies and inflatables had proved inadequate to the task of crossing the strongly flowing Irrawaddy. Negotiations to secure a boat from an elephant tamer identified as Karen (a diverse ethnic group living across South East Asia) had also been unsuccessful. What remained of the 8th column of the Chindits was transported across the river in three trips. Men, mule and radio transmitter then made an arduous upland journey, ascending 1000ft before resting by a shady mountainside stream.

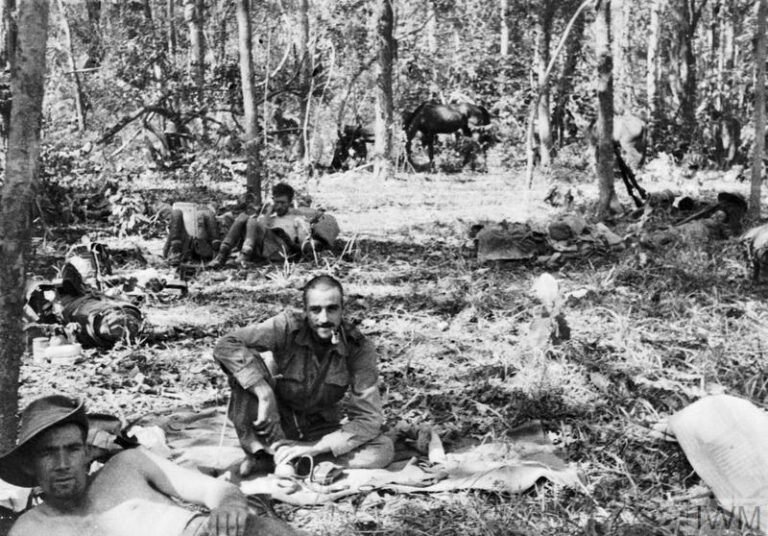

The group had been marching since January. They would march for eight more days before being partially relieved by a Douglas Dakota military transport plane, bringing supplies and evacuating 18 of the sick and injured. This American-built plane must have been an incongruous sight as it landed in a Burmese woodland clearing, circled from above by eight fighter aircraft.

The mule having collapsed from exhaustion had been shot. The radio transmitter it had been carrying was dismantled and buried. Unable to communicate with the army airbase, infantrymen marked the ground to signal to the plane. Soldiers who did not manage to get on board were provided with maps and instructed to make their own way back to India. Many did not survive the journey, died in combat or disappeared. Some of the sick and wounded were left in the jungle or dropped off in the nearest village.

Suffering and censorship

The strategic value of Operation Longcloth has long been disputed given its high casualty rate and limited gains. Of the 3,000 soldiers who marched into Burma at the beginning of February 1943 only 2,182 managed to return to India after encountering unexpectedly strong resistance from the Japanese.[ref]Kirby et al., The War Against Japan: Volume II. India’s Most Dangerous Hour (Dehra Dun, India: Natraj Publishers, 1989), p. 324[/ref]

Japanese officers interrogated by the Allies after the war claimed the British had caused ‘little trouble’; damage was limited to the blowing up of two or three railway bridges, which were repaired within a month.[ref]’Japanese point of view on the Wingate Expedition of 1943-1944′ (1946). Catalogue reference: WO 203/594[/ref] Plans to foment a ‘tribal’ uprising in the hills were also unsuccessful, foiled by inadequate wireless equipment.

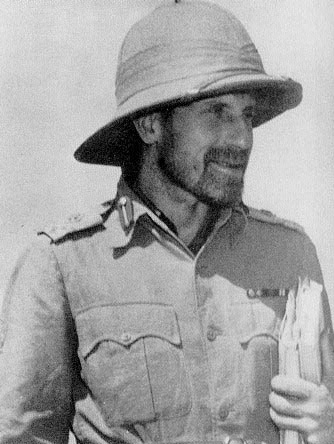

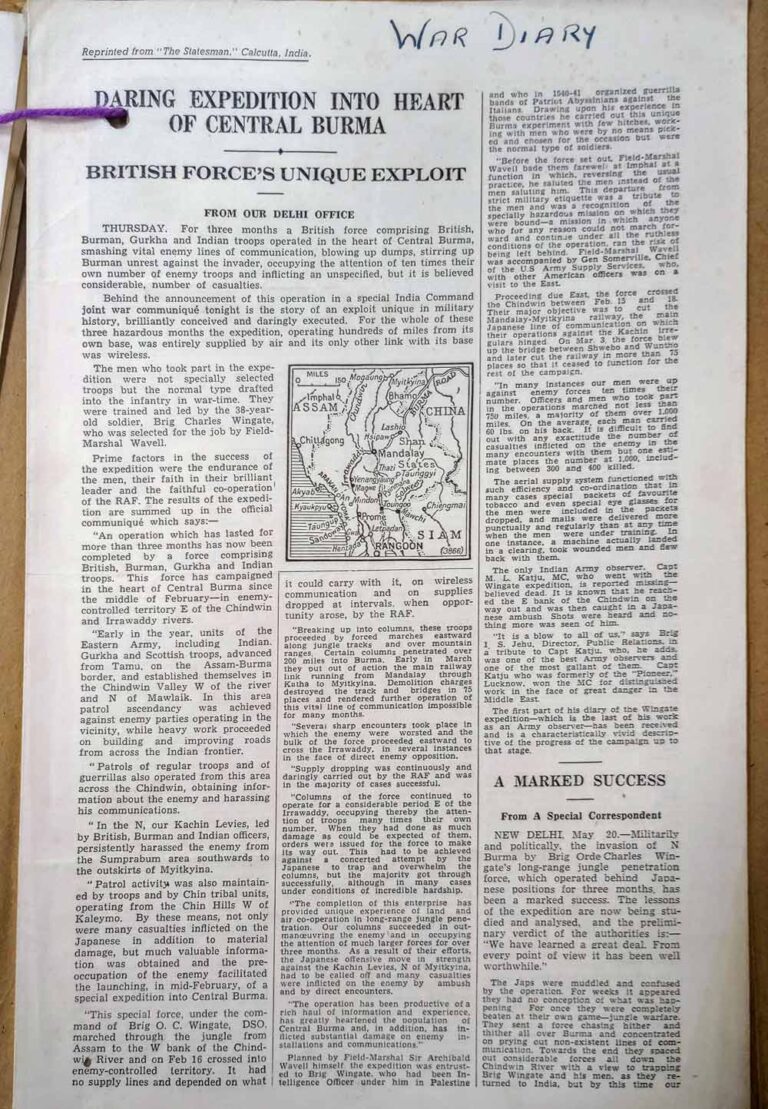

Press coverage at the time, however, depicted the operation as a pioneering exercise in unconventional warfare led by a visionary commander. Wingate was said to have successfully deployed guerrilla tactics encountered whilst serving in East Africa and Palestine, to engage in asymmetrical warfare against the Japanese.

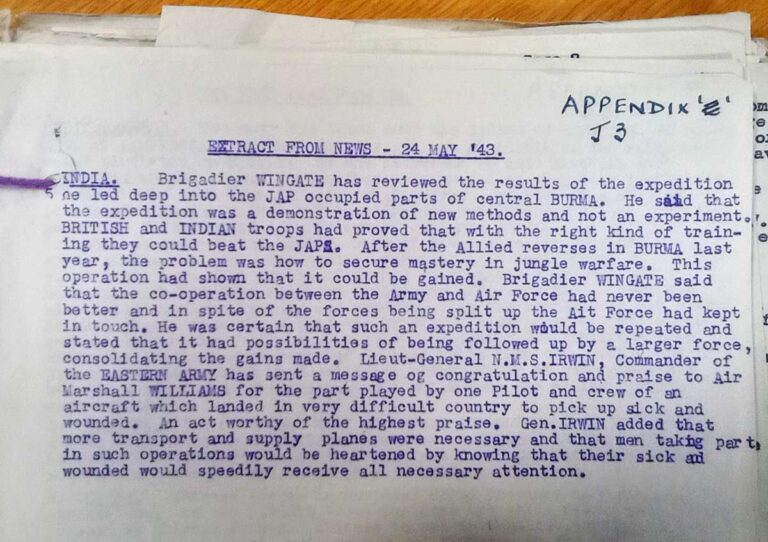

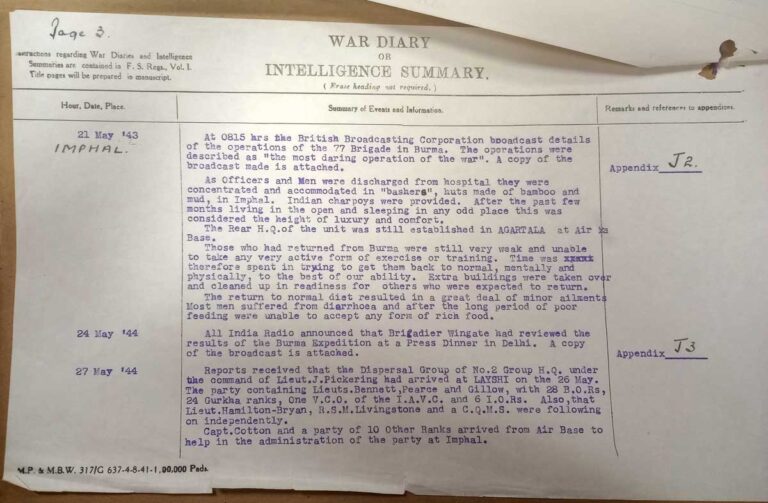

Some of this press coverage is mentioned and included in the war diary entry for May 1943, after the operation had concluded and soldiers were recuperating in Indian hospitals. State broadcasters, the BBC and All India Radio, describe the operation as a success: ‘the most daring operation of the war’, which had succeeded in disabling Japanese communications (the BBC, 21 May 1943). Wingate was quoted as saying the expedition had been a successful demonstration of new methods, proving that, with adequate training, British and Indian troops could beat the Japanese (All India Radio, 24 May 1943). Transcripts of these broadcasts are appended to this war diary.

These positive accounts clash with the details contained in the diaries themselves. Months of carrying heavy loads in the heat had worn these men out. Many of them were malnourished and sick – struggling to adjust to a normal diet, afflicted with beriberi and cerebral malaria. And these were the fortunate soldiers who had managed to return to India. The entry for 10–20 May 1943 relates few of the 13 King’s had yet to make it back.

Positive coverage was not restricted to government-owned media. Unlisted in the appendices but included in the April 1943 war diary is an article from the Calcutta-based newspaper The Statesman, dated May 1943. Based on interviews with Wingate and official communiques, this describes the operation as a ‘marked success’, ‘an exploit unique in military history, brilliantly conceived and daringly executed’.

In correspondence sent in April 1943, The Statesman’s editor, Ian Stephens, described being pressured by the government of India to censor negative coverage of the war.[ref]Bayly and Harper, Forgotten Armies: Britain’s Asian Empire and the war with Japan (London: Penguin, 2005), pp. 274–275.[/ref] But by spring 1943 signs of the great famine that was to hit Bengal in 1943–44 were already visible on Calcutta streets. Many Indians believed this was a direct result of British wartime economic policy.

In August 1943, Stephens was to defy censorship and publish his famous reports on the crisis. Photographs of the dead and starving got round restrictions on describing the situation as a famine. The accompanying articles argued the situation was man-made, a result of mismanagement of resources by provincial and central government, unable to effectively deal with a combination of poor harvests and wartime privations following the fall of Burma in 1942.

Further research

The juxtaposition of voices and perspectives contained in the war diaries highlight the entangled nature of the conflict across the different theatres of war, and also reveal its human costs. Further research into the diaries will allow more thematic strands and connections to emerge, and Michael McGrady has written a useful guide to navigating them. Read against other sources and wider contexts, these documents potentially convey a clearer sense of the global and long-term impact of the Second World War.