I began work in autumn 2016 with Tamasha Theatre and five of their playwrights, on a new project exploring loyalty and dissent in the First World War using our records. This will culminate in a performance of five short plays at the Rich Mix Centre on Friday 31 March.

I have become increasingly fascinated and intrigued – as are many others – by the motivations of the sepoys (Indian soliders serving under the British) who fought in the war. At the same time our records reflect the challenges posed to an all-powerful British imperial state and the tension that existed between soldiers and personnel ‘loyal’ to empire and those ‘dissenting’ voices that sought to agitate and fight to end imperial rule.

This blog intends to briefly explore some of these tensions as a way of providing an introduction to some of our records on these topics. I will look at some of the motivations, exploring ideas such as honour and shame, that tie in closely with ideas around ‘loyalty’. I will then contrast this with those voices of dissent that challenged the imperial state. I will then reflect on some of the challenges in researching and presenting material on these areas of history.

Honour and shame

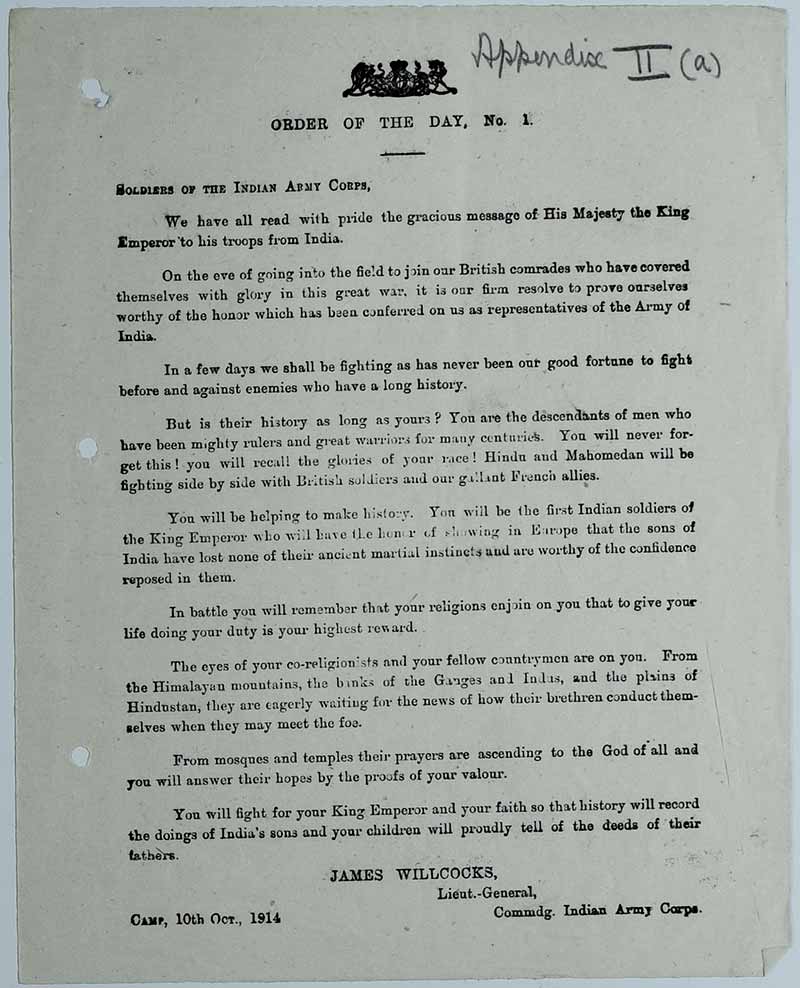

On the eve of the First World War, the British army was ill prepared to create a mass army for a war in Europe. Trained soldiers were needed and the only ones available for immediate deployment were the Indians. Two Indian divisions that were scheduled to go to Egypt were sent to Europe under the command of General Sir James Willcocks.

At The National Archives we have a copy of the ‘order of the day’ signed by Willcocks that was written to rouse the troops in battle. It evoked the kind of emotions reserved for a powerful anthem, ending with:

‘You will fight for your King Emperor and your faith so that history will record the doings of India’s sons and their children will proudly tell of the deeds of their fathers.’

While the Indian Army under the British has often been portrayed as a mercenary force, looking more closely at their military service suggests that the recruits also made a deliberate choice after weighing the benefits and drawbacks of enlistment. What has been equally interesting is the question: what kept them fighting? This requires an examination of other forces, such as honour and shame, which sustained the Indian Army not only during war but also in peacetime.

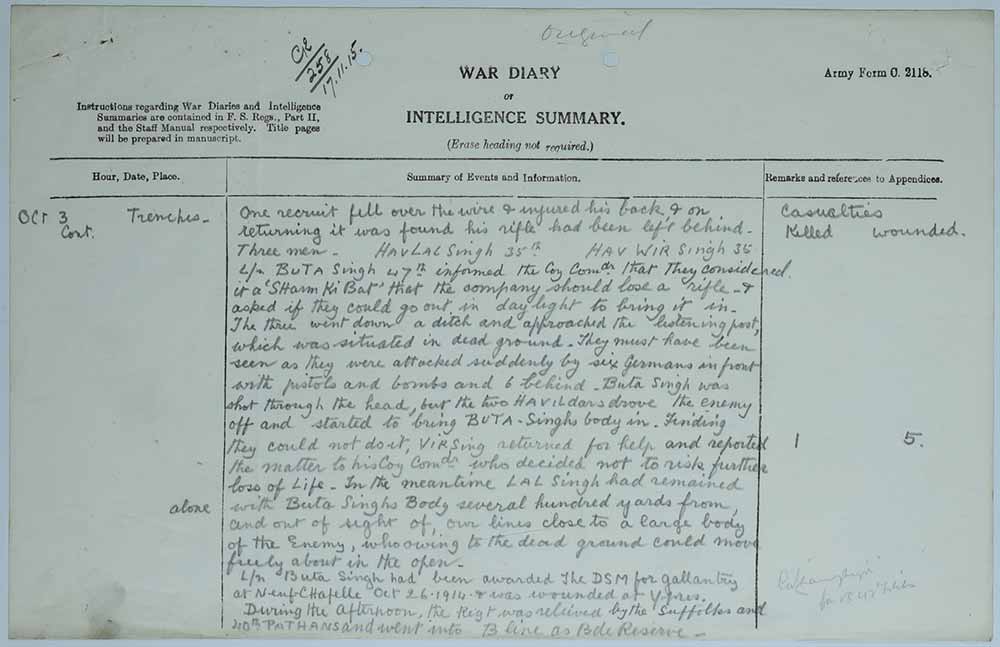

We have a record about Lance Naik Buta Singh of the 47th Sikhs who with a number of colleagues saw it as a matter of shame that a rifle had been left in the field of battle, and in an attempt to retrieve it, he was killed. The idea of shame or ‘sharm’ was seen as disloyalty and a type of cowardice. Shame was also associated with masculine identity and being held to be imperfectly male.[ref]1. David Omissi, ‘The Sepoy and the Raj’, p83[/ref]

War Diary account includes reporting the death of Lance Naik Buta Singh of the 47th Sikhs (catalogue reference: WO 95/ 3927)

Linked to shame was ‘izzat’ or honour: ‘This is the time to show one’s loyalty to the Sirkar, to earn a name for oneself. To die on the battlefield is glory. For a thousand years one’s name will be remembered’, a sepoy wrote. [ref]2. David Omissi, ‘The Sepoy and the Raj’, p79[/ref]. Also a mother wrote to her son in 1917: ‘You went to war in 1914 and are still fighting the King’s enemies on the field of battle. I am heartily grateful to you for the faithfulness and loyalty and will remember it to my dying breath’. [ref]3. David Omissi, ‘The Sepoy and the Raj’, p79-80[/ref]

According to the historian Gajendra Singh, ideals such as ‘izzat’ were widely invoked. These had existed before colonialism was established, however were heightened under imperial rule. This was done alongside promoting the idea of ‘martial races’, the idea that some Indians were more suited to fighting than others.[ref]4. Gajendra Singh, ‘The Testimonies of Indian Soldiers and the Two World Wars’, p 72[/ref]

Radical diaspora

Of course not everyone could be a soldier or serve in the War effort. They either remained a smallholder or emigrated. Those Indians who left and settled, for example, in North America encountered racism and organised themselves politically to fight against anti-immigrant attacks. Initially attempts were made to appeal to the British Imperial State for help. When these pleas fell on deaf ears, the Indians turned once again to India as a place that could fulfil their aspirations.

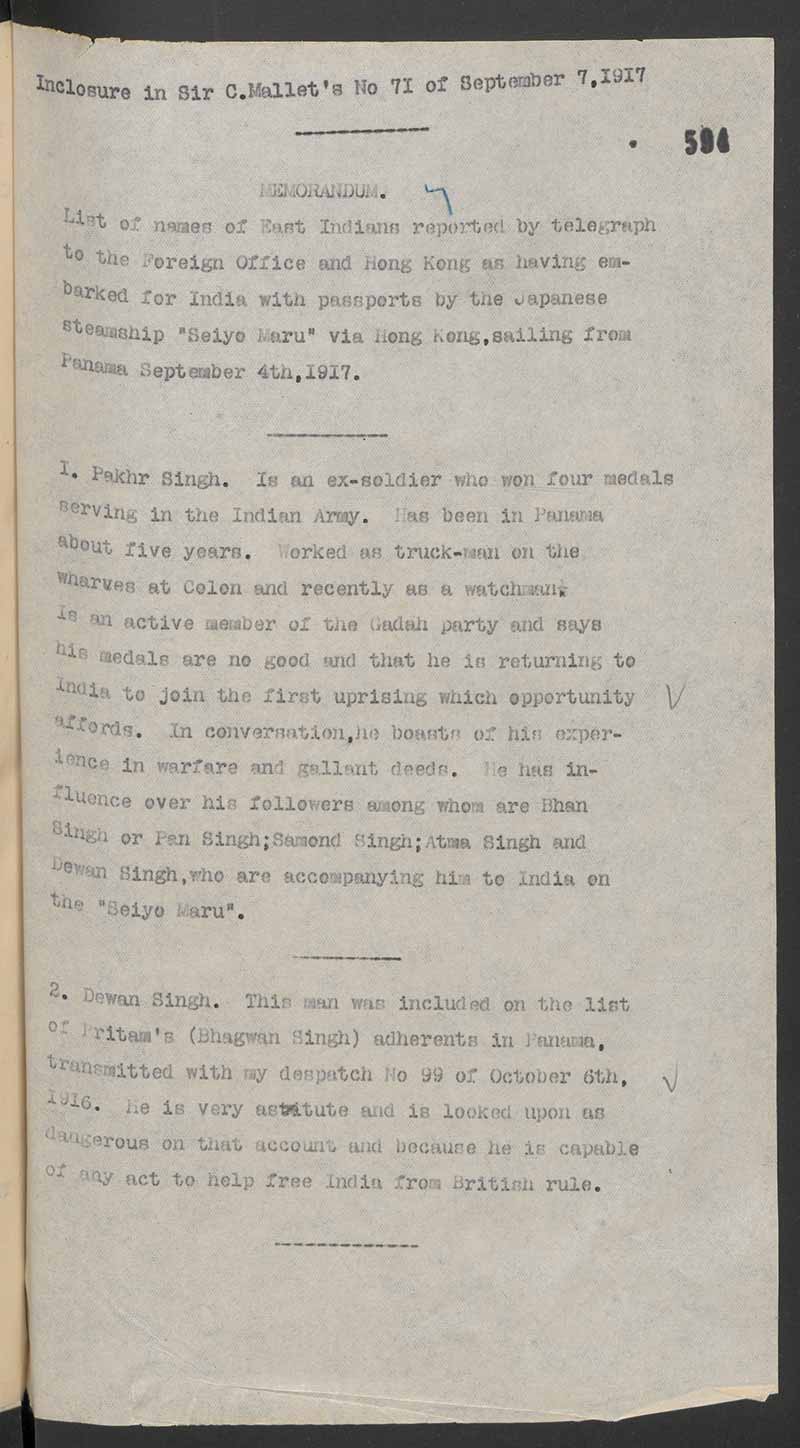

Example from report of alleged seditionist, Pakhr Singh (catalogue reference: FO 288/181)

Maia Ramnath identifies some of the groups which historians have referred to as the ‘radical diaspora’, these include intellectuals, radicals and soldiers. According to a report from September 1917 that we hold on alleged seditious activity, Pakhr Singh is an ex-soldier who won four medals serving the Indian Army. He had been in Panama for about five years and was planning to return to India to cause revolt.

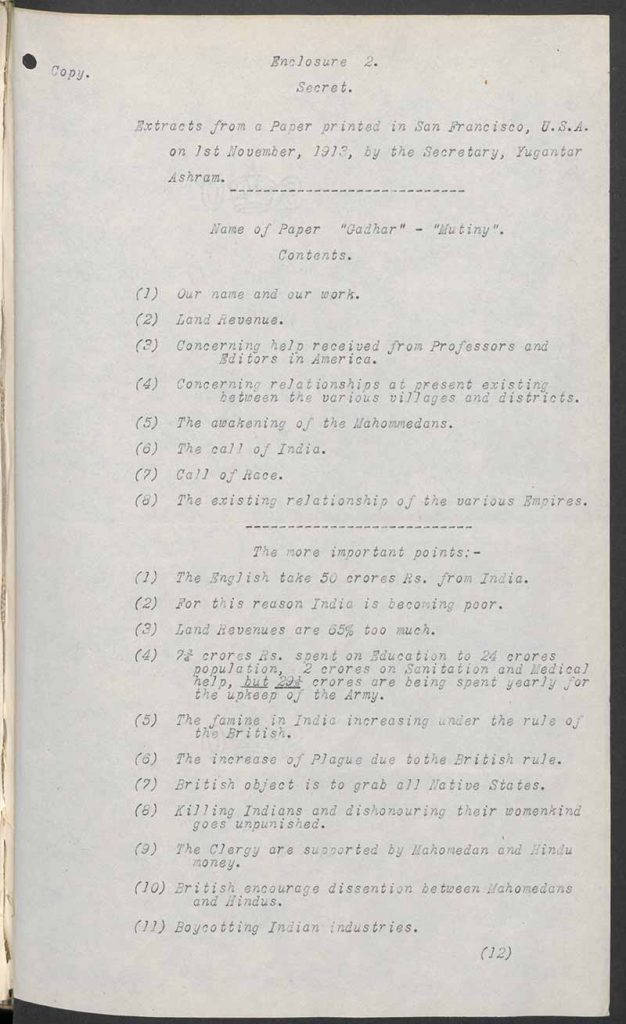

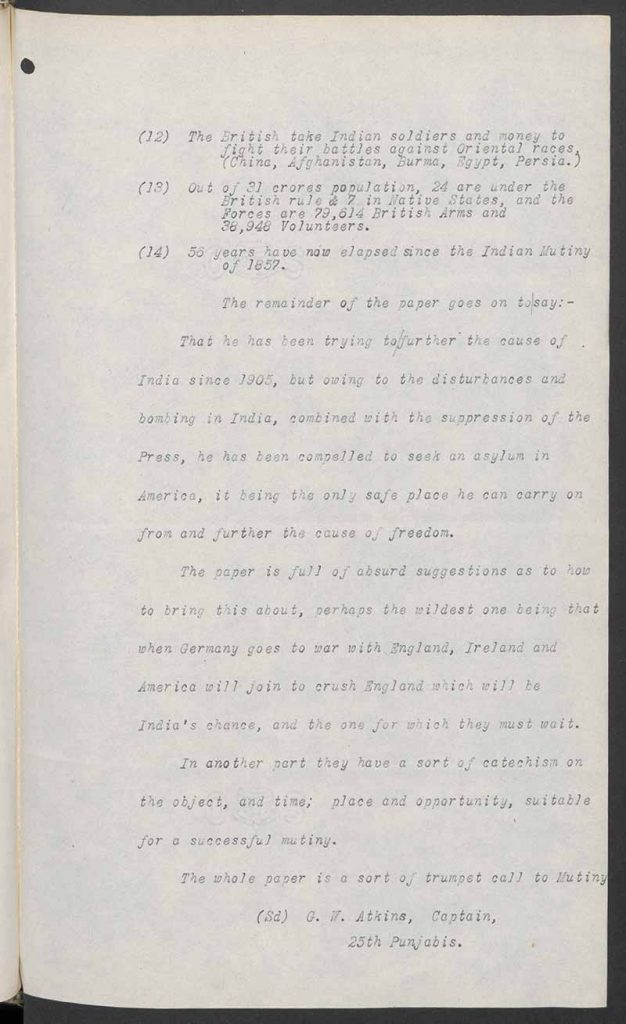

The early pioneers’ attempts to challenge the opposition they experienced were hindered by their poor level of English. The arrival of Har Dayal on the scene is widely recognised as the catalyst for change. He was a brilliant student who partially completed his studies at Oxford before networking with other revolutionaries (including founding the Ghadar organisation) and planned for an armed struggle for the liberation of India.[ref]5. Har Dayal is most closely associated with organising Indians on the West Coast of America and stirring them to revolutionary activity in what became known as the Ghadar movement. Ghadar can be translated as ‘mutiny’ and was also the name given to the newspaper edited and published by Har Dayal in the name of the Hindu Association of the Pacific Coast which was founded in May 1913. The association gave rise to the Ghadar Party. This was not the first or only nationalist organisation on the West Coast supporting revolutionary activity in India.[/ref]

The Ghadar organisation began to expand at a considerable rate and prominent among its members was a large body of Sikh factory workers, farmers, agricultural labourers and students. The war offered a way of channelling the significant rise in popularity of this movement and heralded the start of a return of revolutionaries to India and various plots were hatched.[ref]6. Harjot Oberoi, ‘Ghadar Movement and Its Anarchist Genealogy’, p42[/ref]

- English translation of Ghadar newspaper 1 (catalogue reference: FO 371/2152)

- English translation of Ghadar newspaper 2 (catalogue reference: FO 371/2152)

In 1910, only a few years before General Willcocks’ rousing speech, Canada, one of Britain’s dominions, introduced legislation which made it impossible for Indians to come to Canada.[ref]7. In 1907 the Canadian government stipulated that all immigrants arriving from Asia would only be permitted if they had $200 and in May 1910 they made entry even more difficult by passing the continuous journey provision. This made it impossible for Indians to come to Canada as there was no direct journey from India.[/ref] This was challenged in May 1914: a ship from Hong Kong carrying 376 passengers (mostly immigrants from the Panjab), led by Gurdit Singh, arrived in Vancouver; the passengers, all British subjects, fell foul of the exclusionary legislation. The ship, the Komagata Maru, was denied docking by the Canadian authorities and only 20 returning residents and the ship’s doctor and family were allowed admission to Canada.

The events in Canada and Europe in 1914 somewhat perfectly illustrate the tensions between loyalty and dissent: the stalemate in Vancouver lasted two months and on 23 July 1914 the ship was forced to sail back to India, and met by gunfire and the killing of 19 passengers. In Marseilles in September and October 1914 Indian troops coming to fight on behalf of the British and French were being garlanded and biscuits were distributed!

Researching loyalty and dissent

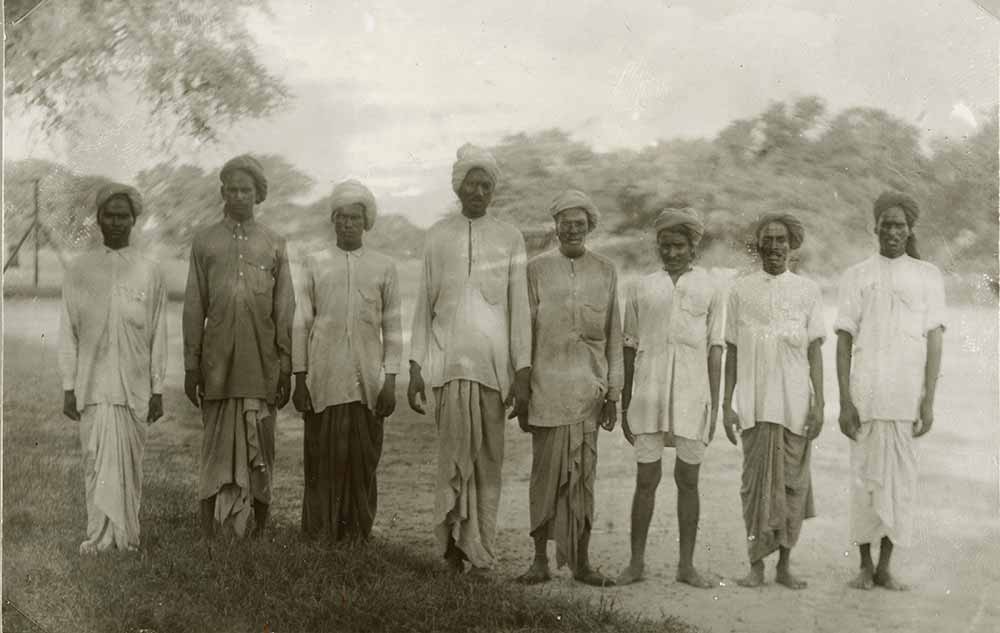

Photograph of Sikhs as ‘raw recruits’ for the army (catalogue reference: CN 4/8)

This image from our collection show recruits, and is catalogued as Sikh ‘raw recruits’. It may have been similar men who enlisted to fight in the First World War. At the time these men would have been enlisted, the literacy rate was very low; in the Punjab no more than 5% could read, and among rural military communities this was even lower. And this poses a considerable challenge for the historian who seeks to find a contrasting voice to that contained within the official records.

One example of how this manifests itself is the challenge in using what has become a very important source for the Indian soldiers in the First World War: the letters that the soldiers sent and received. [ref]8. The collection is currently housed at the India Office Library (part of the British Library) and consists of 4000 pages.[/ref] The censors read the soldiers’ mail and then sent a report to various government departments. The objective was not to stop communication that was held to be unfit, but to monitor morale and ensure that issues arising relating to food and religious observances were attended to. David Omissi points out that in reading these letters it is not simply a matter of eavesdropping on the innermost thoughts of the soldiers, or looking invisibly over their shoulders as they write: the vast majority were written by scribes on behalf of the soldiers. In addition, the problem in using scribes was that it would make the letters a more public record than a simple correspondence between two literates.

Commemorating the role of South Asians in the First World War has remained problematic. In the years leading up to and following India and Pakistan’s independence, the First World War was perceived as a colonial war which was not part of modern South Asian history. In Britain there also remained an uncomfortable silence on the role of colonial troops and personnel in how the war was conducted, and eventually won, which only started to be addressed more recently. The 100th anniversary of the war has offered an opportunity to review and acknowledge more fully the diversity of contributions made. It has also set new challenges including the very real need to move away from sanitising the story of South Asia and the First World War.[ref]9. Late last year I began working with the Dr Santanu Das from Kings College and others on planning a forum at the University on the topic of South Asia and the First World War. Santanu has done some very important work in not only highlighting the cross disciplinary nature of this endeavour but also the very real need to move away from sanitising the story of South Asia and the First World War.[/ref]

The National Archives’ project on South Asia and loyalty and dissent in the First World War is one contribution to what is a complex and difficult story.

Further reading

George Morton Jack, ‘The Indian Army on the Western Front’

Rozina Visram, ‘Asians in Britain’

Harjot Oberoi, ‘Ghadar Movement and Its Anarchist Genealogy’

David Omissi, ‘The Sepoy and the Raj’

Maia Ramnath, ‘Two Revolutions: The Ghadar Movement and India’s Radical Diaspora, 1913-18’

Gajendra Singh, ‘The Testimonies of Indian Soldiers and the Two World Wars’

Gajendra Singh, ‘Revolutionary Networks’ (part of 1914-18 online)

Very interesting blog post. I write about Indian nationalists and Italian anarchists in a forthcoming book chapter in this book: http://www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk/9781784993412/

You have done a very interesting work these photos and comments from rechive is very fascinating I hope you will go on producing such blogs congratulations.

I blog about the Singapore Mutiny, and other things

ppaanderson.wordpress.com

[…] National Archives blog on the project: Loyalty and dissent in the First World War […]