It is that time of year again when the football posts come down and cricket squares are cut across parks and village greens. From a personal perspective, British summer is built around the sound of leather cricket ball whacking against willow bat (or clattering into one’s stumps!), usually via the relaxing ambience of BBC’s Test Match Special.

Today’s blog – the latest in our series of First World War Military Service Tribunal posts – looks at a cricketing-themed case. The immediate view of this case would be to see it as a weak claim for exemption from military service; on further reflection, it reveals the growing demand for men to serve in the British Army as the war progressed.

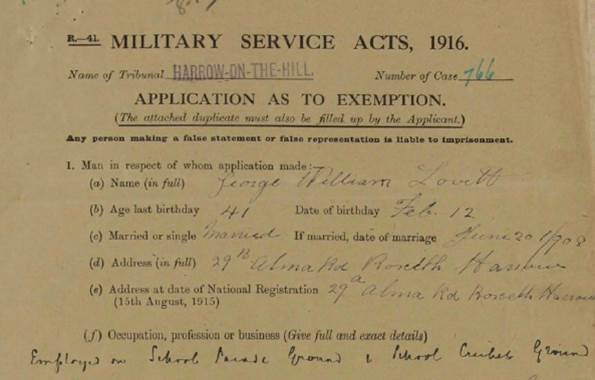

Application for exemption for George William Lovett, confirming his employment at the Harrow School (catalogue reference: MH 47/94/23)

George William Lovett, aged 41, of Alma Road, Roxeth was employed by the Harrow School from around December 1914 to maintain the school’s cricket and parade grounds. In February 1917, the Assistant Master of the school applied to the Harrow on the Hill local Military Service Tribunal for George to be exempt from compulsory military service on that grounds that his work was of national importance.

The application form records the decision of the local tribunal at Harrow, stating that ‘the application be not accepted on the grounds of insufficient reasons for so doing’ (MH 47/94/23). On the face of it, being employed to maintain the parade ground and cricket pitch does not fit suitably with the term of work of ‘national importance’.

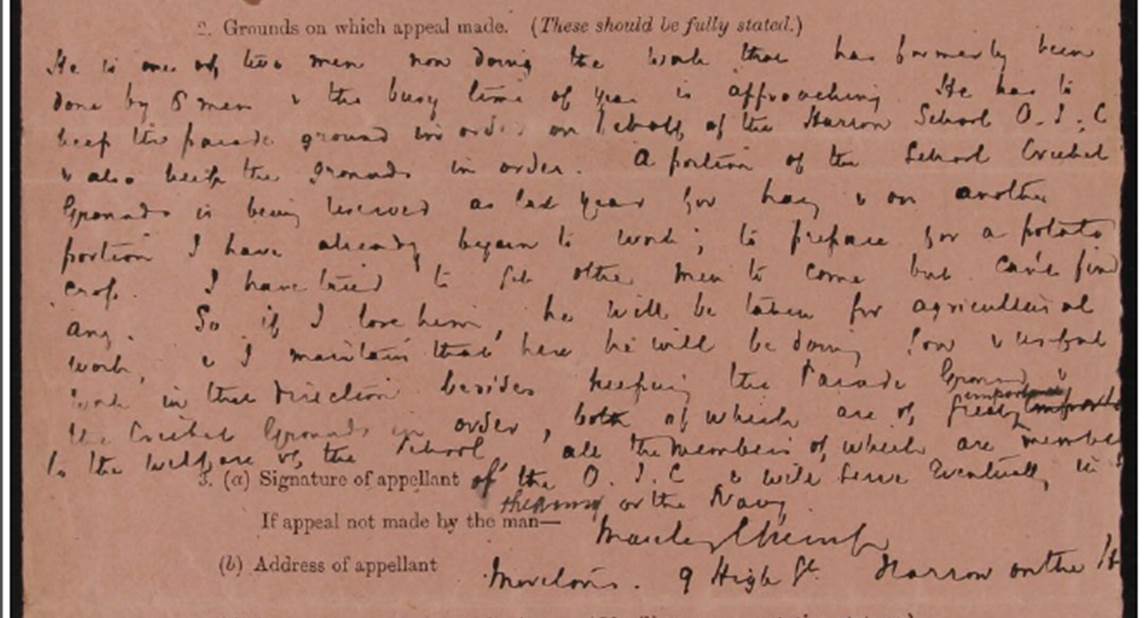

Harrow School subsequently appealed against this decision and took their case to the Middlesex County Appeal Tribunal, which was heard on the 11 April 1917. The appeal form that the Assistant Master completed provides us with a more detailed summary of the situation at Harrow. In the personal statement to outline the grounds of appeal, it is stated that George is one of two men now doing the work that had been undertaken by eight previously. Likewise, George’s call up to service is also right upon ‘the busy time of year’.

Appeal form for George William Lovett detailing the extended work he was carrying out (catalogue reference: MH 47/94/23)

Crucially, the appeal statement details the work George is employed to do. Far from cutting the cricket square as spring turns to summer, George was tasked with maintaining the parade ground for the Harrow School Officer Training Corps, designed to help develop future officers for the British army. Likewise, parts of the school’s cricket grounds were being put to use for agricultural purposes, including a potato crop in April 1917.

The statement continues by revealing that the school had made efforts to recruit alternative men to carry out this work to free George for service, but had failed to find any.

So, having moved from a local tribunal application form to the appeal form, we get a very different insight into the specifics of the case. Rather than sounding like a weak application, we can now see that George was carrying out work that did include some agricultural elements, as well as supporting efforts to generate future officers for ‘the Army and Navy’.

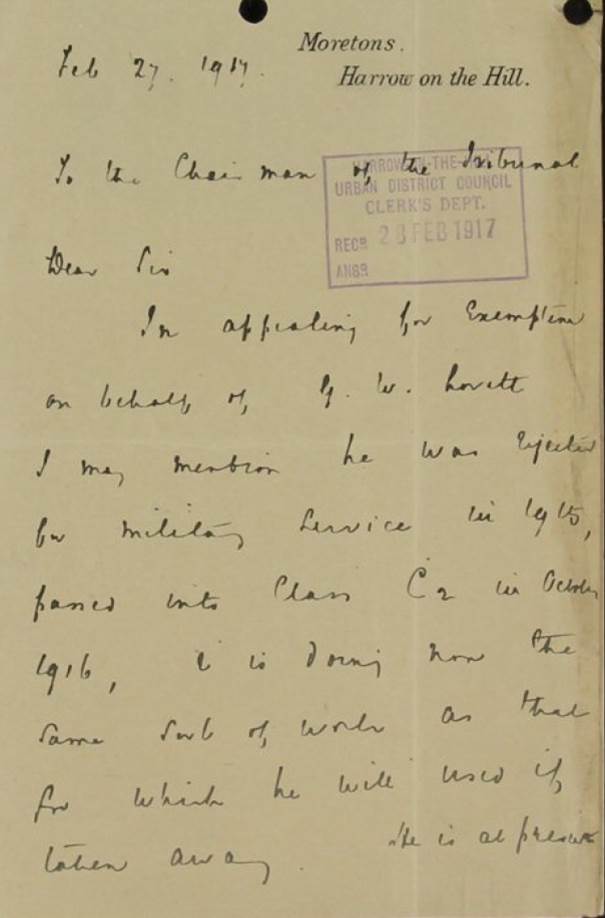

In addition to the application and appeal forms, this case also benefits from some supporting evidence surviving within the papers. This is the form of a letter submitted by the school to the tribunals to further outline their case. In it, the school reveals that George had previously been rejected for military service in 1915, when it was still a voluntary recruitment system. Likewise, in October 1916, George had been allocated to the military medical grade of C2. This means that George was only liable to serve in garrisons at home and was not considered fit enough for service overseas.

Letter to tribunal from Harrow School highlighting George’s previous attempt to enlist (catalogue reference: MH 47/94/23)

So, again, another crucial point arises. Those who sought exemption should not all be seen as deliberately trying to avoid service. Many would have tried to join voluntarily, like George, but been considered unfit. As the war progressed, as losses increased and as the army expanded, these medical assessments would have changed to help meet the numbers required. Likewise, calling on older men to serve at home in Britain would then free younger men to serve overseas.

The appeal form also provides a little more insight from the local tribunal, who describe why they made their initial decision to reject this case. Here they state that in their judgement, the boys of the school could be called upon to carry out these tasks, to free a man of military age for future service. While not wishing to argue either way on this view, I do think that it shows the added responsibilities expected of all ages across the home front during the First World War. Men and women, girls and boys, the young and the mature were all called upon to contribute at some point.

The appeal tribunal confirmed the decision of the local tribunal to dismiss George’s case. I cannot find any additional information regarding his subsequent service, suggesting that he did carry out his period in the Army in the UK and as such not qualifying for any campaign medals.

I hope that this blog highlights the impact of war across society at home in Britain during the war. Efforts to support the war effort reached far and wide across the UK including school sports fields. People of all ages were increasingly expected to assist, while those of an older age and previously unsuitable fitness were called upon to do their bit stationed at home.

The next time I hear the soothing sound of leather on willow, I will stop and reflect upon George’s case and the contribution made across the country to supporting the wider war effort.

To search our collection of Middlesex based tribunal records, which are free to download and view, please see our online search page. This now includes a list of surviving tribunal papers for the rest of England and Wales, kindly researched by members of the Federation of Family History Societies.

Have you checked AIR 79/2589/296764 for George. Another case in the same area is the Perrin family (of Sudbury Court Farm) who claimed successfully for exemption for a period because they needed to get the harvest in which was used to supply hay to the Army for the horses in the field.