The methods used by Special Operations Executive (SOE) agents to pass as members of the local population in Nazi-held territory were carefully thought out; they were never used lightly or over-egged, and required subtlety and understatement. Disguises or camouflage were used in a number of cases but there were alternative means by which SOE agents managed to ‘pass’ as locals in the area they operated, or in the identities they had assumed.

The incidence of cases where agents needed to use disguises was thus relatively small. Disguises were usually adopted where an agent had to return to the place where they had been active, after narrow escapes from Axis personnel and where their identity had become known.

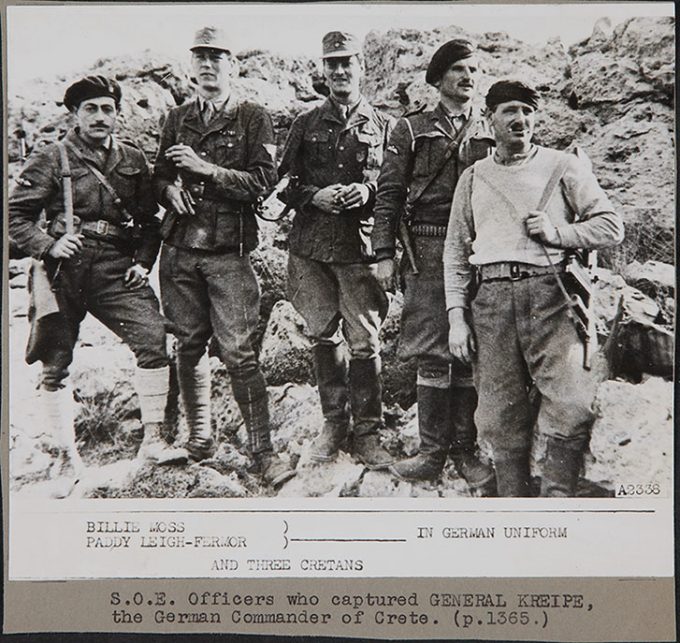

SOE Mid East-Balkans April-Dec 1944 Capturers of Gen Kreipe – Crete. Catalogue reference: HS 7/273

Putting on an act

To be convincing, much depended on agents having the background on which their false identity was based. For them to ‘pass’ and not attract attention when approached or questioned, they needed to be able to behave naturally and in character. For many this went well beyond simply ‘putting on an act'[ref]Behind Enemy Lines: SOE agents and the art of ‘Passing’ – Juliette Pattinson[/ref].

Some key means of enabling agents to ‘pass’ were:

- Recruiting men and women who had a background in the place they were going to be operating in – people who had parents born abroad, or who had grown up or lived or worked abroad; who could speak the local language fluently, and who understood the local customs.

- Adopting a credible identity – some agents, such as Francis Cammaerts, head of the Jockey circuit, would have three or four, only one of which he would carry papers for at any time, but which he could switch between quickly.

Agents would try to assume identities that they could use to register for genuine identity papers, rations cards, permits to travel etc. This meant that if their papers were checked, there would be no chance of them being found to be forgeries for people who didn’t exist. This was another ploy practised by Francis Cammaerts, among others.

When this wasn’t possible, SOE had an excellent forgeries department which was able, among other things, to produce a passport purportedly belonging to Adolf Hitler and a stamp bearing the likeness of Himmler, head of the SS!

Being kitted out in clothing made not only in the local style but also using local weaves was not just important for ‘blending in’ – it had serious implications on the agent’s security. SOE employed tailors experienced in creating clothes that were typical of particular European countries, and for good reason: the German Sicherheitsdienst (SD – Security Police) employed specialists to examine the weave of clothing, and British weaves, being different from continental weaves, would have been easily identifiable.

Sometimes for women agents, posing under identities of the well-to-do, this meant having to parachute into France with quite elaborate and extensive wardrobes in their luggage. One particular agent parachuted into France but became separated from her possessions. She went to a café in a nearby town and ordered a coffee. Imagine her surprise when another woman came in with her suitcase and began selling her SOE-produced clothes. And then her horror when the SD arrived and took the woman for questioning!

Agents had access to excellent intelligence and information to use for negotiating their way around the locality they worked in, including handbook guides for Paris and other parts of France. Also available, where possible, was knowledge of German counter-espionage tactics. For example, in a number of cases only the circuit leaders knew the identities of all the group leaders and of intermediaries. A ‘cut-out’ system of letter drops was used whereby the person holding the letter did not know the identity of either the ‘sender’ or the ‘recipient’.

Maps had to be kept up-to-date and were printed on cloth so that they did not tear or rustle. On one occasion, the famous Christine Granville was stopped by a German patrol. She quickly hid her map by folding it diagonally and putting it on as a headscarf! The German soldiers did not realise that the bright pattern was actually a map!

Many SOE agents operating in clandestine roles were recruited as civilians, or before any military training and bearing had hardened out. They would walk and talk as civilians – advantageous as, to an experienced eye, any person with a military bearing would clearly stand out in the company of civilians. All this is very different from acting. This is the art of ‘non-projection’, as opposed to theatrical character projection and playing for attention. It is the art of blending into the audience.

Disguises

Disguises would be kept to a minimum. A cosmetic disguise applied sparingly for a woman could be explained away but an elaborate disguise on a man would be a complete giveaway. Wigs were not a good idea unless a man was visibly balding! Most disguises revolved around changing the way hair was combed or wearing glasses with a different style of frame – something that was not suspicious if a person was being questioned.

Something else that really helped agents was the training they received in giving cover stories under duress. This typically was the point at which an awful lot of candidates applying to become SOE field agents were failed.

It helped that a lot of agents had nerves of steel; they were well-practised in the art of dissembling, and could switch this on and off at will. None more so than Christine Granville, who was arrested twice by the Germans or their agents, and who managed to lie her way out. On one occasion she bit her lips and produced blood – the Germans waved her on as quickly as possible. The Germans had a phobia about tuberculosis during the Second World War and SOE agents were taught about this.

It was generally easier for female agents to pass themselves off as locals. The Germans, as per the culture of the day, tended to notice women a lot less. If that didn’t work some calculated flirtation would often be enough to get them past patrols or checkpoints! On one occasion SOE agent Juno Alexander was carrying a bomb in a suitcase strapped to her bicycle. A German guard approached and demanded to know what was in the bag. She replied jokingly that it was ‘a bomb, of course’. She was waved on! The trick, ‘of course’, was to appear natural.

Not all SOE field operatives operated as clandestine secret agents. In Greece, Yugoslavia, Crete and the rest of the eastern Mediterranean, Africa and the Far East they overwhelmingly operated in uniform. Paddy Leigh Fermor and Bill Stanley Moss adopted the ultimate disguise for the Kreipe kidnapping on Crete, by wearing German uniforms and posing as German officers during the abduction!

Sources

SOE: France: circuit and mission reports and interrogations: Cammaerts to Cruzel (HS 6/568)

Histories and War Diaries: Lecture folder STS 103; part 1 Date: 1943–1944 (HS 7/55)

Histories and War Diaries: Lecture folder STS 103: part 2 minor tactics and field-craft, demolitions and physical training syllabus Date: 1943–1944 (HS 7/56)

SOE group B training manual regional supplement: France, Netherlands and Norway. Note: with two photographs (on identity cards), two maps and sample Date: [c.1940–1945] (HS 7/66)

Group B syllabus (in the Finishing Schools) (HS 7/52)

History of the Training Section of SOE 1940–1946 (HS 7/51)

Recruitment and training: Lectures and statistics Date: 1942 Jan 01–1942 Dec 31 (HS 8/371)

Documents made by IV W: Germany; identity cards, driving licences, work papers. Date: 1942 Jan 01–1945 Dec 31 (HS 8/1033)

SOE Personal File Francis Cammaerts ‘Roger’ aka JOCKEY (HS 9/258/5)

SOE Roger Landes aka ARISTIDE (HS 9/880/8)

SOE Personal File Christine Granville aka Krystyna Skarbeck aka ‘Pauline’ (HS 9/612)

Special Operations Executive: Station 15b Exhibition: Photographs (HS 10/1/9)