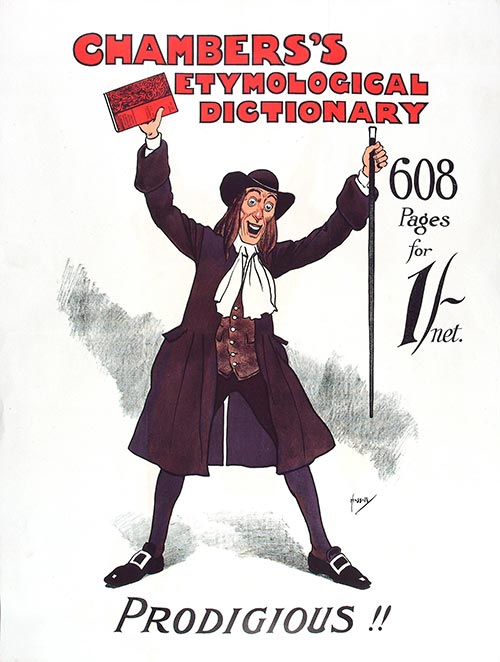

Chamber’s Etymological Dictionary poster, 1903. Catalogue ref: COPY 1/208B (22)

Words have always been a vital part of how we communicate on many levels of human emotion. They can make you feel good, sad, and angry, they can make you laugh and even cry. Cultural and social change in society can also create and establish new words or phrases. We may dismiss these as ‘slang’ – but where do they come from, and why do they stick with us?

When William the Conqueror invaded Britain in 1066, our English language merged with the Latin tongue and a transition from Old English to Middle English began. Latin was the main language of the church, law and government. Even Domesday Book was written in Latin, which William used to govern his new kingdom. ‘A Dictionary of Medieval Terms and Phrases’ provides clarity on the precise meaning of Old English and Middle English and it gives examples of medieval terms and phrases still in use today. This is a dictionary to help both specialists and general readers decipher both everyday ordinary medieval words and the legal and ecclesiastic terminology of that period.

The cover of ‘The Stories of Slang’

Music, TV, and celebrity have a great influence on our mainstream vocabulary today and, not least, technology. The internet also pushes the boundaries of language and it’s hard to go a week without coming across a new ‘Twitter-born’ word or phrase. In such a fast-paced world we want to communicate as quickly as possible, as we text away on our mobile phones in a sort of Morse code, abbreviating or combining words to mean one of the same thing. ‘The Stories of Slang – Language at its most human’ is a fascinating look at how centuries of slang came to epitomise many aspects of our social life in everyday human existence. It looks at how slang has been used to describe uncensored experiences around sex, the body and its functions and from the effects of intoxication, drink and drugs, with related phrases such as ‘drunk as a Lord’ and ‘hair of the dog’.

In the 1600s, London was the place to be, if you were any kind of a writer. Among the publishing houses, where dialect was standard and the spelling and grammar were fixed, the first English dictionary was published in 1604. Shakespeare, for so many the greatest writer of the English language, was a devotee of the double entendre and master of the pun: he caused nearly 300 slang terms to be set down in print and used just over 500 ‘slang’ terms and clichés, such as ‘what the dickens’, ‘bated breath’, ‘for goodness sake’ and ‘love is blind’.

Moving forward, we borrow from cockney rhyming slang – ‘rabbit and pork’ talk – which originated in the East End of London; we have also inherited First World War trenches slang, which emerged as soldiers huddled in their trenches waiting to go over the top into no-man’s land. Phrases such as ‘have a field day’, ‘zero hour’, ‘mad minute’ and ‘over the top’ were brought back from the trenches and used in civilian life. ‘Lingo of No Man’s Land’, is a First World War dictionary of 1918 and gives a fascinating insight into life on the front line.

The cover of ‘Jackspeak’

The Navy has given us plenty of slang too: ‘plain sailing’, ‘flogging a dead horse’ and ’money for old rope’. The naval community once had its own language, incomprehensible to anyone who was not a sailor – but when it came to shore leave these seafaring men would introduce aspects of their language to the populations of bustling ports and harbours, and the usage slowly spread inland.

‘Not Enough Room to Swing A Cat’ provides a compilation of naval slang throughout the world, from terms relating to ship-handling and seamanship through to food and drink, discipline and insults. This is a detailed and highly entertaining book, with text that is enhanced with original black line drawings to illustrate certain technical terms, such as ‘splice the mainbrace’.

For the Senior Service – in other words, the Royal Navy, the Royal Marines and the Fleet Air Arm – and, well, for all sailors, ‘Jackspeak’, is another great classic book, a revised and expanded third edition, featuring many new additions and updates. It is a comprehensive reference guide packed with humorous and colourful slang, introducing new generations of Jack, Jenny and Royal to life in the Andrew. Along with excellent illustrations by Tugg, the cartoonist from service newspaper Navy News, it is the essential book for current and ex-Navy personnel.

Just to represent the junior British armed service in its centenary I offer ‘gone for a Burton’ meaning to be killed.

Unlike the US version (‘bought the farm’ referring to life insurance payout) its origin is more obscure.

I have heard reference to Burton Ales (as in a drink in memory of the deceased) or Burtons the high street taylors, referencing the practice of mourners wearing a dark suit to the funeral and/or the deceased being so dressed for burial.

William The Conquerer did not invade Britain, he invaded England.