Tonight on BBC One’s Six Wives with Lucy Worsley, the spotlight falls on the trial of Anne Boleyn, and some of the records pertaining to this most famous inquiry are held at The National Archives.

Admire her or question her motives, it is undeniable that, out of all of Henry VIII’s six wives, Anne Boleyn courted the most controversy. The tale of Anne’s rise and fall is familiar to most of us. Henry pursued Anne while still married to his first wife, Katherine of Aragon, and he separated from Rome in order to divorce Katherine and marry Anne in 1533. Anne never enjoyed popularity as queen and ultimately failed to produce a male heir. After Anne miscarried for a second time in January 1536, Henry was on the hunt for ways to end his second marriage.

Whether or not Anne’s destruction was engineered by Thomas Cromwell, Henry’s chief secretary, has been much debated by historians.[ref]1. There is extensive literature on this topic. See especially: G. Walker, ‘Rethinking the Fall of Anne Boleyn’, The Historical Journal, 45:1 (2002), 1-29; E. W. Ives, ‘The fall of Anne Boleyn reconsidered’, English Historical Review, 107 (1992), 651-664; G.W. Bernard, ‘The fall of Anne Boleyn’, English Historical Review, 106 (1991), 584-610.[/ref] What is clear from the evidence is that there was an inquiry into Anne’s personal and sexual conduct, which was prompted by various accusations against her, including infidelity.

Anne’s fall from power was rapid. By April 1536, a commission was established to investigate rumours about her conduct and on 2 May, Anne was arrested and charged with committing adultery with five men, including her own brother, George, Lord Rochford, and other members of the king’s privy chamber: Henry Norris, William Brereton, Francis Weston, and the musician Mark Smeaton.

According to Cromwell, in a letter held at the British Library, dated 14 May 1536, to Sir John Wallop and Bishop Stephen Gardiner at the French Court, the queen’s licentious behaviour was so ‘rank and common that the ladies of her privy chamber could no longer conceal it’; and that members of the Council were informed about her activities, who had passed the information to the King.[ref]2. J. Gairdner (ed.), ‘Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, of the Reign of Henry VIII, Vol. 10: 1536’ (London, 1887), 873[/ref]

You can view documents relating to the trial of Anne Boleyn, and her brother, George, at The National Archives; they are held in a file of the proceedings of the court of King’s Bench, KB 8/9. These are records of the special commissions of oyer and terminer, or the court of the Lord High Steward and peers, which tried peers of the realm who were accused of treason. The records were originally kept separately from other indictments, in a bag known as the ‘Baga de secretis’, or ‘Bag of Secrets’, because it was a state trial, the trial of a crowned queen and was therefore considered particularly important.

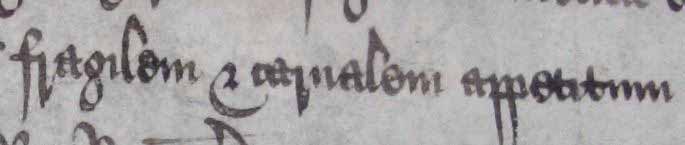

The records indicate that the formal charges were laid against Anne, her brother and accused lovers, at Westminster on 9 May and divided into two cases. On 12 May, Smeaton, Norris, Brereton and Weston were brought before the court but only Smeaton admitted guilt. The others maintained their innocence but were found guilty of adultery with the queen and sentenced to execution at Tyburn. Anne and her brother’s case was heard on 15 May and they were likewise found guilty of adultery and sentenced to execution. Despite the charges being couched in formal Latin, the language of the court, the tone adopted is certainly derisive towards Anne; for example she is described as following her ‘fragilem et carnalem appetitem’ or her frail and carnal sexual appetites,[ref]3. Catalogue reference: KB 8/9, f. 9r[/ref] and this could indicate that her accusers believed her to be guilty.

Extract from the indictment listing the charges against Anne Boleyn (catalogue reference: KB 8/9, f. 9v)

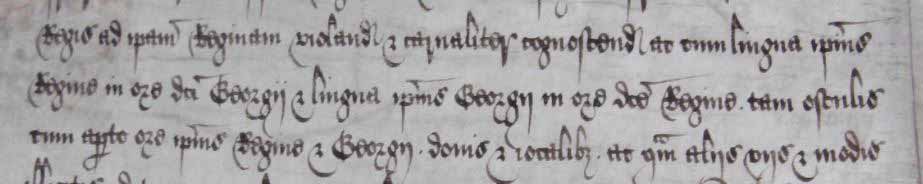

One of the more disturbing charges that was brought before Anne was that she had incited her own brother, George Boleyn, to have sexual intercourse with her, specifically on 2 November 1535, but also several times before and after, at Westminster. The language used here is also particularly explicit: ‘Reginam violandam et carnaliter cognoscendam ac cum lingua ipsius Regine in ore dicti Georgii et lingua ipsius Georgii in ore dicti Regine tam osculis cum aperte ore ipsius’. So the Queen is described as ‘alluring him with her tongue in the said George’s mouth, and the said George’s tongue in hers, with their eyes wide open’.[ref]4. Catalogue reference: KB 8/9, f. 10r[/ref]

Detail of alleged incest between Anne and George Boleyn (catalogue reference: KB 8/9, f. 10r)

This description of the unnatural affair between brother and sister is followed by an accusation that Anne, along with several of the men with whom she had conducted affairs, had been plotting Henry’s death and that she had promised to marry one of the traitors after the king’s death, affirming she would never truly love Henry. This sealed her fate.

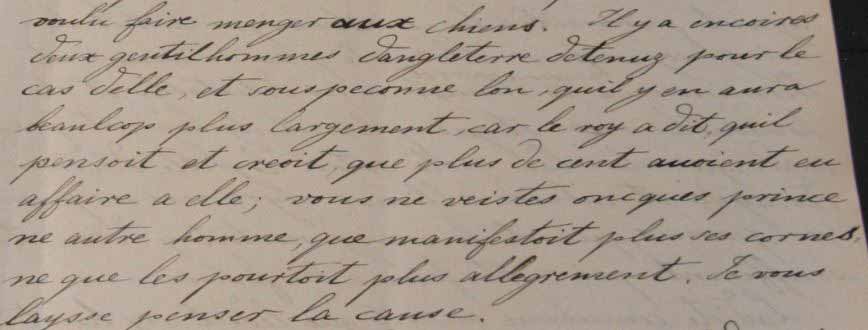

News of Anne’s alleged indiscretions quickly reached Europe. Eustace Chapuys, the diplomat and imperial ambassador to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who is famous for his extensive correspondence, certainly made his attitude towards the ‘Royal concubine’ painfully clear. Chapuys wrote to his patron, Nicholas de Perrenot, on 18 May; we have transcripts of some of his letters at The National Archives, in French, from the Imperial Archives in Vienna. The letter is written after the actual trial had taken place and Chapuys comments that he is not surprised that this is the case, because the king believes that she has had sexual relations with over 100 men.[ref]5. Catalogue reference: PRO 31/18/2/2, f. 246r[/ref]

Eustace Chapuy’s diplomatic correspondence detailing the extent of Anne Boleyn’s alleged infidelity (catalogue reference: PRO 31/18/2/2, f. 246r)

No matter whether there was any truth in the allegations against Anne Boleyn, the letters held here at The National Archives certainly show that Anne was not well regarded by her contemporaries. The explicit and damning language describing the Boleyn crimes in the records suggests that the outcome of the case might indeed have been predetermined.

[…] techadmin on December 14, 2016 Six Wives in the archives: the trial of Anne Boleyn2016-12-14T10:20:49+00:00 – Journals & Publications – No […]

GOOD.AFTERNNON,ARCHIVE

The Latin “… tam osculis cum aperte ore ipsius Regine et Georgii” would seem to be referring to open-mouthed kisses, not open eyes.

Kisses, pl. dat. or abl. = osculis (sing. osculum); eyes, pl. dat. or abl. = oculis (sing. oculus). Mouth, sing. abl. = ore (sing. nom. os) The adjective aperte modifies ore, thus “with open mouth”.

The earlier part of the sentence says George was “violating the Queen, and knowing her carnally”, and doesn’t say anything about Anne alluring anyone.

I realize it’s a bit late to comment on this page, but those are pretty big differences in quotation meanings. Are you folks sure that the correct portions of the transcript were quoted?

Hope this helps.