Almost 100 years ago, a revolution in government occurred: the first systematic and official record of a Cabinet meeting was created on 9 December 1916. There were other significant changes – a smaller war cabinet and a Cabinet Secretariat to give support, which became the Cabinet Office.

The National Archives is marking this forthcoming centenary with a display in our Research and Enquiries Room and an online resource.

It seems surprising to modern day observers that before 1916 the Cabinet had met without an agenda and secretary, and ministers took action on their recollection of what had been decided at meetings. Prior to 1916, the main archival sources for Cabinet decisions are private letters written by the Prime Minister to the Sovereign after each meeting. The non-existence of official minutes reflected the ‘old school’ approach of ‘a gentleman’s word is his bond’; however, it could result in misunderstandings and confusion.

Military background

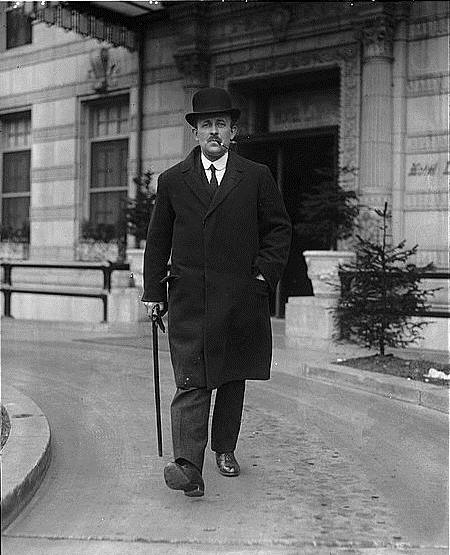

Sir Maurice Hankey, 1921 (Library of Congress)

One man was instrumental in shaping the new streamlined processes of modern government: Sir Maurice Hankey. It is interesting to note that Hankey was not a typical civil service bureaucrat who had risen to a senior grade after a long departmental career. His background was military, initially active service as a Royal Marine officer, and he soon made a great impression, being appointed to the Naval Intelligence Department in Whitehall in 1902.

In 1908 he took up a new role as Assistant Secretary to the Committee of Imperial Defence (CID), which was the principal advisory body on home and overseas defence matters up to September 1939. Although the power of this body was limited, as it lacked executive functions, it carried out useful work. Hankey became Secretary of the CID in 1912 – a post he held until his retirement in 1938.

From his early days with the CID, Hankey ensured that its records were meticulously organised. Through his long period of involvement with defence planning and coordination, Hankey built up a huge fund of knowledge and experience which was to serve him well as Cabinet Secretary during the new era of ‘total warfare’ represented by the First World War (and the increasing tensions of the inter-war years).

Origins of the Cabinet Secretariat

In late 1916 the war was going badly: there had been huge loss of life on the Somme. During a conference of the Allied leaders in Paris in mid-November, David Lloyd George, Secretary of State for War, and Lieut. Col. Maurice Hankey went for a ‘stroll’ and exchanged views.

According to Lloyd George’s War Memoirs, during this walk, Hankey suggested to him that he should ‘insist on a small War Committee being set up for the day-to-day conduct of the war, with full power’.[ref]1. David Lloyd George, ‘War Memoirs, Vol.II’ (Boston, 1933), 369: cited in John F. Naylor, ‘A Man And An Institution: Sir Maurice Hankey, the Cabinet Secretariat and the Custody of Cabinet Secrecy’ (Cambridge University Press, 1984), 8[/ref] Hankey and Lloyd George were very concerned about the outdated mechanisms of government which were straining under the demands of modern warfare. The Cabinet had been hampered in its conduct of the war by its large size, its lengthy and unfocused discussions, and a lack of coordination across government.

Instant modernisation

When Lloyd George became Prime Minister on 7 December 1916, one of his first actions was to insist on a smaller war cabinet, with just five members.[ref]2. By 1918 the War Cabinet had expanded slightly, to six or sometimes seven members. Throughout the war other attendees could be invited to meetings, including military chiefs, ministers and non-ministers.[/ref] The main purpose of this change was to speed up the decision-making process.

By 9 December he had appointed Hankey as Secretary to the War Cabinet. This amounted to instant modernisation for Cabinet government. In the words of Professor Peter Hennessy, ‘in the space of a week in December 1916, Lloyd George and Sir Maurice Hankey streamlined the Cabinet system along the lines pioneered by the Committee of Imperial Defence’.[ref]3. Peter Hennessy, ‘Cabinet’ (Basil Blackwell, 1986), 16. The CID methods included formal minutes and memoranda and sub-committees to work on intricate issues.[/ref]

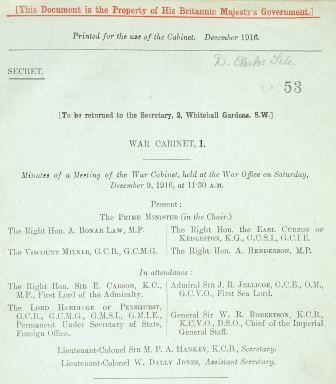

Cabinet minutes, 9 December 1916 (catalogue reference: CAB 23/1)

Hankey, as Cabinet Secretary, began the practice of taking the minutes (or conclusions) at meetings of the Cabinet. He also helped to coordinate the efforts of politicians and military chiefs. But it was not feasible for him to act as a ‘one man band’. Administrative support was needed, in order to circulate memoranda (papers for discussion) to the members of the Cabinet and its committees, and to be responsible for the safekeeping of papers created out of the business of the executive.

So a Cabinet Secretariat developed, to give this administrative support (and to ensure good communications across government); over time, this secretariat became known as the Cabinet Office, and Hankey was at the heart of it. He drew up the rules of procedure for the Cabinet, prepared agenda, and, as well as taking the minutes, he ensured that the decisions were implemented by the departments concerned.

‘Incredible memory’

Through his meticulous efficiency, Hankey brought order to Cabinet government, and he was revered for his special qualities in this regard. Sir Robert Vansittart, Permanent Secretary at the Foreign Office in the 1930s, described Hankey in some memorable phrases:

‘A marine of slight stature and tireless industry, he grew into a repository of secrets, a Chief Inspector of Mines of Information. He had an incredible memory…an official brand which could reproduce on call the date, file, substance of every paper that ever flew into a pigeon-hole. If St Peter is as well served there will be no errors on Judgement Day’.[ref]4. Cited in Hennessy, ‘Cabinet’, 17[/ref]

Tributes on retirement

For Lloyd George, Hankey was the ‘organiser of victory’ for the First World War, and he continued to build up a strong Cabinet Office in the interwar years. He carried out the demanding role of Cabinet Secretary for an amazing length of time, from 1916 to 1938.

Fulsome tributes were paid to him on his last day in this role – at Hankey’s last Cabinet meeting Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain said: ‘he had gained the respect and affection of every one of them, and they would miss him greatly’. In his touching response, Hankey declared that

‘he was glad that he had continued to serve the Cabinet for so long. He regarded himself as perhaps something of a robot, but robots had their feelings, their criticisms and their admirations. So far as he was concerned, since the present government had been in office, criticism had been lacking and admiration had been continuous. He would like to end on one word which the Prime Minister had used, “affection”.'[ref]5. Cabinet meeting, 28 July 1938 (catalogue reference: CAB 23/94, CC 36(38)8)[/ref]

Lord Hankey continued to be consulted by ministers and civil servants after his retirement as Cabinet Secretary, and he joined Chamberlain’s war cabinet. Winston Churchill appointed Hankey as Paymaster General in July 1941, but he expressed criticisms of Churchill’s conduct of the war and was dismissed by the PM in March 1942.

Through his dedicated public service, and his superb organisational talents, Hankey made a massive contribution to the system of cabinet government. His work endures – as John F Naylor wrote, ‘not only did Hankey establish the Secretariat as the agency for the conduct of Cabinet government, but as well he laid out the institutional paths which his successors continue to tread’.[ref]6. Naylor, ‘A Man And An Institution: Sir Maurice Hankey, the Cabinet Secretariat and the Custody of Cabinet Secrecy’, 7[/ref]

Explore history

From the First World War and General Strike to the Suez crisis and development of Concorde, explore historical moments through our Cabinet records: www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/cabinet-office-100

Nice piece on Hankey but probably best not to spell Chamberlain’s first name incorrectly?

Hi Gordon,

Thanks for your comment. I’ve corrected Chamberlain’s first name.

Best,

Nell

Lord Hankey was the first Chairman of the Scientific Advisory Committee of the Cabinet and a reader of the MAUD Report at the end of August 1941. The famous MAUD Report concluded that a bomb was possible and that it would take two and one-half years to develop. As Hankey’s secretary the report was likely to be first handled by John Cairncross. Cairncross was first named as the “fifth man” in 1990 by Soviet double agent Oleg Gordievsky, who defected to Britain in 1985. See Christopher Andrew and Oleg Gordievsky, KGB: The Inside Story (New York: HarperCollins, 1990), pp. 216-217, 261-262, 279.

It is also worth mentioning that Hankey kept a diary for much of his time as Cabinet Secretary, and that significant extracts from that diary (and his letters to his family) were punlished in Stephen Roskill’s 3 volume “Hankey: Man of Secrets” published in the early 1970s. These volumes are invaluable for an understanding of Hankey and the genesis & early years of the Cabinet Office, and give fasciniting insights into the personailities of the PMs and other senior cabinet members who Hankey worked closely with.