It is amazing how a quiet afternoon at The National Archives can provide an opportunity of discovery of unknown history within our collections. Searching online through the Calendar of Patent Rolls, in record series C 66, I found an entry relating to a knight I had not come across before: Sir Hugh John.

Dated 18 April 1452, the entry records the appointment of Sir Hugh as steward to the manors of Redwick and Magor in the Welsh marches (present day Monmouthshire) by King Henry VI. There is nothing unusual in this; the king would send numerous letters ‘patent’ (‘open’) granting lands or positions of office annually to favoured subjects across the land.

What is uncommon is the explanation for Sir Hugh receiving the office in the first place. The grant was given because of the outstanding military service in France, but also to the Byzantine Emperor of Constantinople (now Istanbul) and the Genoese dynasty of Cyprus and Armenia. It reads in places almost like a 20th century citation for conspicuous military service:

‘Grant for life to Hugh John, knight, who has laboured against the infidel Saracens in the parts of Troy, Greece and Turkey by land and water and received the order of knighthood at the Holy Sepulchre and visited the Holy Land, as appears by letters apostolic and letters of the Emperor of Constantinople and the king of Cyprus and Armenia for good service in the king’s wars in France, Normandy and elsewhere beyond seas, of the office of steward of the lordship and courts of Magor and Redewike in the march of Wales to hold himself or bydeputies with the usual wages, fees and profits. By P[rivy]. S[eal]. etc.’

The entry states that the Byzantine Emperor, either John VIII Palaeologus (1425-1448) or Constantine IX (1449-1453), had personally written to Henry commending the loyal and faithful service of Sir Hugh. This exceptional commendation suggests that he had distinguished himself in the services of the emperor, or certainly that the emperor had valued his services enough to bestow such recognition.

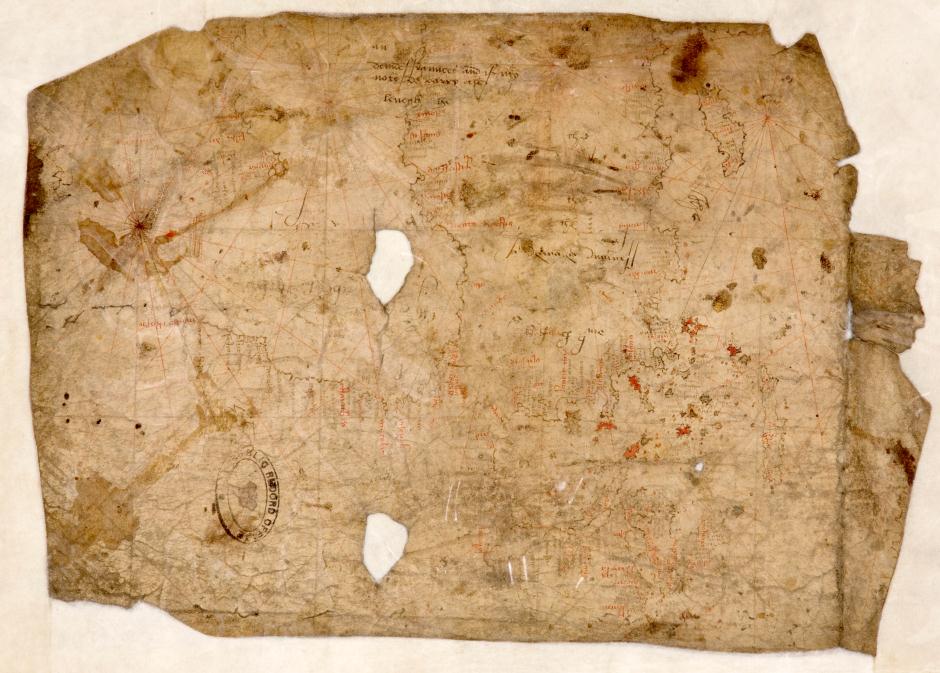

14th century portolan chart of the eastern Mediterranean and western Black Sea. It reveals the extent of Sir Hugh John’s military service (catalogue reference: MPB 1/38; map extracted from E 122/165/10).

The Byzantine Empire, which at one time spanned Greece, the Balkans and most of modern-day Turkey, was a remnant of its former self by the 15th century. Sustained military pressure from the Ottoman Turks for nearly two centuries had gradually reduced the empire to lands around the capital Constantinople and isolated outposts in south eastern Europe.

Ruins of coastal Byzantine fortress in the historical region of Troas, north west Turkey (author’s picture)

A trickle of volunteers, including Sir Hugh, had streamed from Europe to aid the struggling empire, but efforts to enlist the military support of Western Christendom had by and large failed.

The ‘citation’ reveals that Sir Hugh had fought in parts of Troy, Greece and Turkey, on land and sea, against the ‘Saracens’, a term usually used to describe the Muslim people of the Near East. Let us unpack this military service a little more. As Anatolia (most of modern day Turkey) had been almost entirely under Turkish control for a century, any military activity carried out by the Byzantine Empire would have been limited. Sir Hugh may have taken part in naval patrols, expeditions or raiding parties on the Turkish mainland close to the imperial capital, or joined raids orchestrated by the military order of the Knight’s of St. John’s Hospital. The latter operated from their bases at Rhodes, Kos and the fortress at Bodrum, south-western Turkey, the last remaining Christian stronghold on the Anatolian mainland.

Coast of ancient region of Troas. Sir Hugh John may have participated in raids along this coast (author’s picture)

The use of the term ‘Saracens’ could refer explicitly to forces of the Mameluke Sultan of Egypt. Egypt had been attacked in 1421 by the Christian rulers in Cyprus, referenced in the above ‘citation’. In retaliation they invaded Cyprus, forcing its rulers to acknowledge Egyptian sovereignty. There were also frequent naval skirmishes with the Knights of St John, whose stronghold on Rhodes was even besieged between 1440-1444. Sir Hugh may have been fighting in this theatre of operations.

Turning to Greece, only the lands of Morea (southern Greece) and isolated cities such as Thessalonica were still ruled by the Empire. Therefore Sir Hugh could have participated in the defence of cities such as Thessalonica or at the court of the Despotate of Morea located at Mistra (Mystras).

Unfortunately we can only speculate, as we do not know when during the 15th century Sir Hugh actually fought in the east.

There are however clues indicating when Sir Hugh was fighting for the English crown in France from the Treaty Rolls and Garrison Musters transcribed on the Medieval Soldier Database. Treaty Rolls in C 76 documented English diplomatic activity, trade and business with foreign kingdoms. They are also known as the French rolls because much of the business entered onto the rolls was concerned with France. Entries for the reigns of Henry V and Henry VI have been published and translated in the Deputy Keepers Reports, produced by Keepers of the Public Record Office in the 19th century. These can be consulted at The National Archives on the open shelves in the second floor reading room.

According to the C 76 enrolments a knight by the same name appointed attorneys to manage his affairs and represent him in any legal disputes while he was serving abroad on 12 April 1448. A knight by the same name was recorded in the garrison in the French town of Falaise later in 1448. The entry says that he was serving in the personal retinue of the renowned English captain Sir John Talbot.

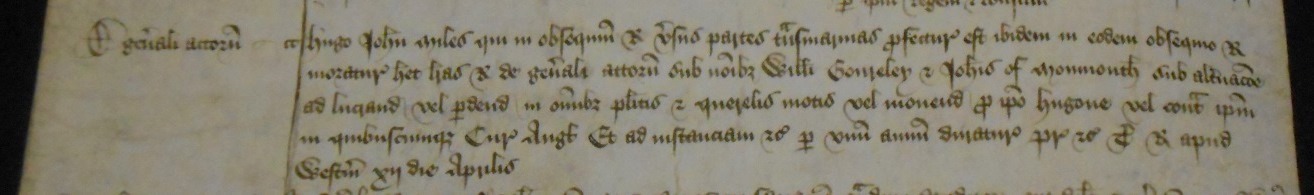

Entry recording appointment of William Goureley and John of Monmouth as general attorneys (catalogue reference: C 76/130 m.8)

Transcription of Sir Hugh John’s name in the garrison muster for Falaise (cited at www.medievalsoldier.org)

Setting aside his military career, what also sets Sir Hugh apart is his pilgrimage to the Holy Land and being knighted in one of the most sacred places in the Medieval Christian world, the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem! He is one of a handful of Englishmen to visit Jerusalem during this period.

Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives. Sir Hugh John would have seen a similar view of the city over five centuries ago (author’s picture)

The Treaty rolls in C 76 reveal the names of individuals such as Nicholas Yeo and Sir William Bowes who were granted licence by the king to travel on pilgrimage to the Holy Land (catalogue reference: C 76/122 m.28 and C 76/108 m.6). Yet for some reason no licence can be found for Sir Hugh. Despite this, the pinnacle of his professional career was being perhaps the only 15th century English soldier to receive the order of knighthood at Christianity’s holiest site.

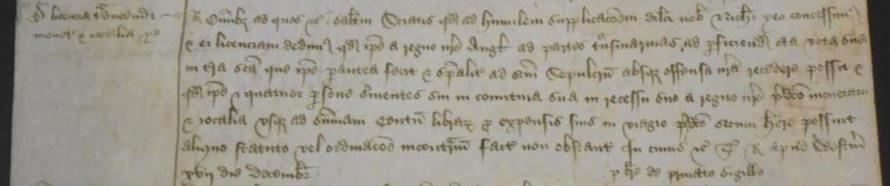

Licence granted to Nicholas Yeo to the Holy land to fufill his vows, with four servants and withdrawing £100 for expenses (catalogue reference: C 76/122 m.28)

The unexpected insights that our records can provide into individuals otherwise lost to history is fantastic! It lets us take a glimpse into the unique career of a knight who received laudable recognition from an Emperor, the Church and the King of England! Such a knight reflects many of the ideals of knighthood described in the romances of King Arthur and the knight in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

[…] It is amazing how a quiet afternoon at The National Archives can provide an opportunity of discovery of unknown history within our collections. Searching online through the Calendar of Patent… Go to Source […]

This is probably the same Sir Hugh Johns who proposed marriage to Elizabeth Woodville in 1451. Two letters of recommendation, written by Richard, duke of York, and Richard Neville, earl of Warwick, attest to his great qualities. They can be found in the British Museum. I suspect that negotiations with the Grey family were well advanced at this time, because she married Sir John Grey of Groby who later lost his life at the Battle of St Albans in 1460. She later married Edward IV in 1464.

Sir Hugh Morrill of Ipswich, Essex, England, born 1520, died1590, was my 9th great-grandfather.