My recent post on the sinking of the Konigsberg gave an overview of the events that unfolded from the time the SMS Konigsberg left Dar-es-Salaam at the outbreak of the First World War until its sinking in the Rufigi delta nine months later.

This blog will look at the sinking of HMS Pegasus, a British warship tracking the Konigsberg, and at some of the records that show the human cost of the nine month engagement.

Sinking of the Pegasus

Correspondence shows that with the departure of HMS Astraea, another British warship, Pegasus commander John Ingles took over the duties of senior naval officer, east coast of Africa. He was ordered to ‘remain at Zanzibar’ as the nature of his duties required his constant presence in harbour.

The defence of Zanzibar consisted at this time of one company of King’s African Rifle, and a very badly organised Local Defence Forces of about 30 Europeans, commanded by a young and inexperienced officer. Ingles reported that during absences from harbour, there were frequent panics of an undesirable nature. These and many other less important matters influenced Ingles, to no small extent, to remain in harbour at Zanzibar whenever it was possible to do so. However he was frequently under weigh, visiting Dar-es-Salaam, Tanga, Bagamoyo and Vanga, but was never away from Zanzibar for more than 48 hours (ADM 137/10).

It was while returning from an operation to land a ‘native’ (local hunter) at Ras Kimbigi, who was willing to examine the Rufigi delta for signs of the Konigsberg, that Ingles’ engineering officer approached him on the subject of the Pegasus’ engines. He highlighted that if they did not soon get an opportunity to adjust the bearings, he was afraid that they would not be able to steam at full speed when required. This was on 15 September 1914 and steam had been on the main engine since leaving Mauritius on or around 25 July 1914, so maintenance work was required (ADM 137/10). The merchant vessel UCSS Gascon was expected to arrive at Zanzibar 20 September with stores and rations for Pegasus, so it was decided to carry out the work (ADM 137/8).

At about 05:00 on 20 September 1914, the watch noticed a ship in the Northern pass and called for the officer of the watch. He was not sure if there was something there, so called the first lieutenant. He examined it and saw that it was a piece of land.

Shortly after, shots were fired and fell short, ‘action’ was sounded, and the control party were ordered to start firing at 7000 yards.

It is reported that the Konigsberg had her range correct at the second salvo; she opened fire at 9000 yards and closed to 7500. The Konigsberg’s shooting was accurate, while the Pegasus shots were all falling considerably short. All engaged broadside guns were disabled after eight minutes and fire ceased from the Pegasus; the Konigsberg left the harbour, firing on the Hellutt, a lookout vessel, on its way.

As Pegasus was badly holed a tug was procured to tow her to shallow water, where she was grounded. The tide and wind subsequently drove her in to deeper water where she sank at 14:30.

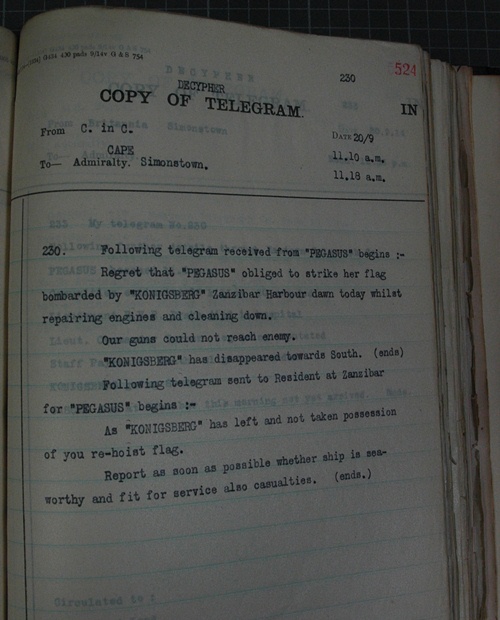

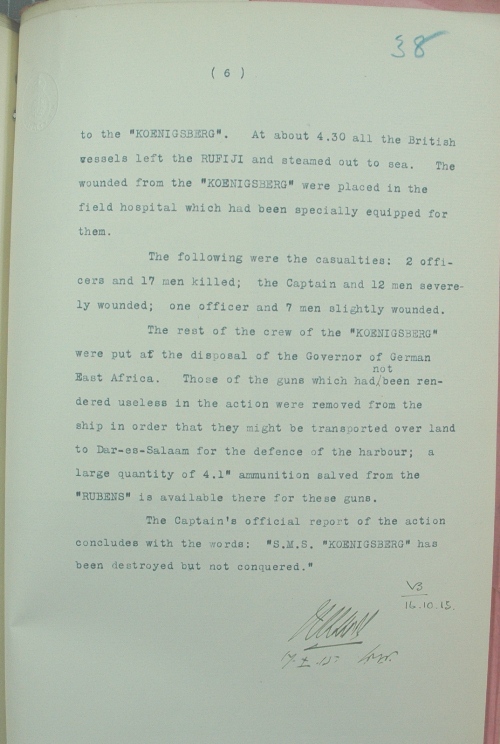

Report that Pegasus had to strike her flag after being surprised by Konigsberg (catalogue reference: ADM 137/9)

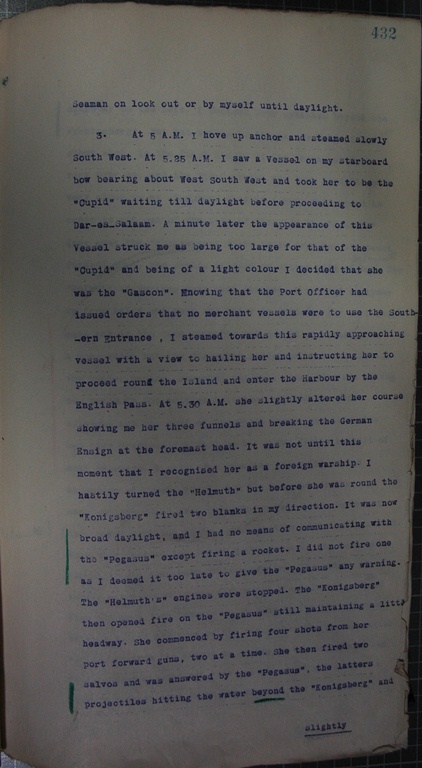

Correspondence shows that that the failure of the lookout vessel to give early notice of the approaching Konigsberg was due to the officer in command mistaking her for the Gascon, whose arrival was expected about that hour (ADM 137/10). A catalogue of events left the Pegasus vulnerable and exposed.

Correspondence shows that the Pegusus being laid up meant that she did not stand a chance against the attack, as she was outranged by the Konigsberg (ADM 137/8).

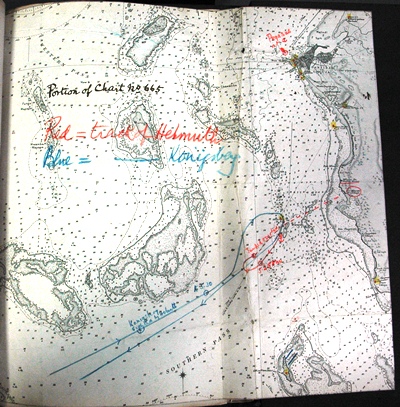

- Report detailing events (catalogue reference: ADM 137/8)

- Document comparing the range of the SMS Konigsberg and the HMS Pegasus (catalogue reference: ADM 137/8)

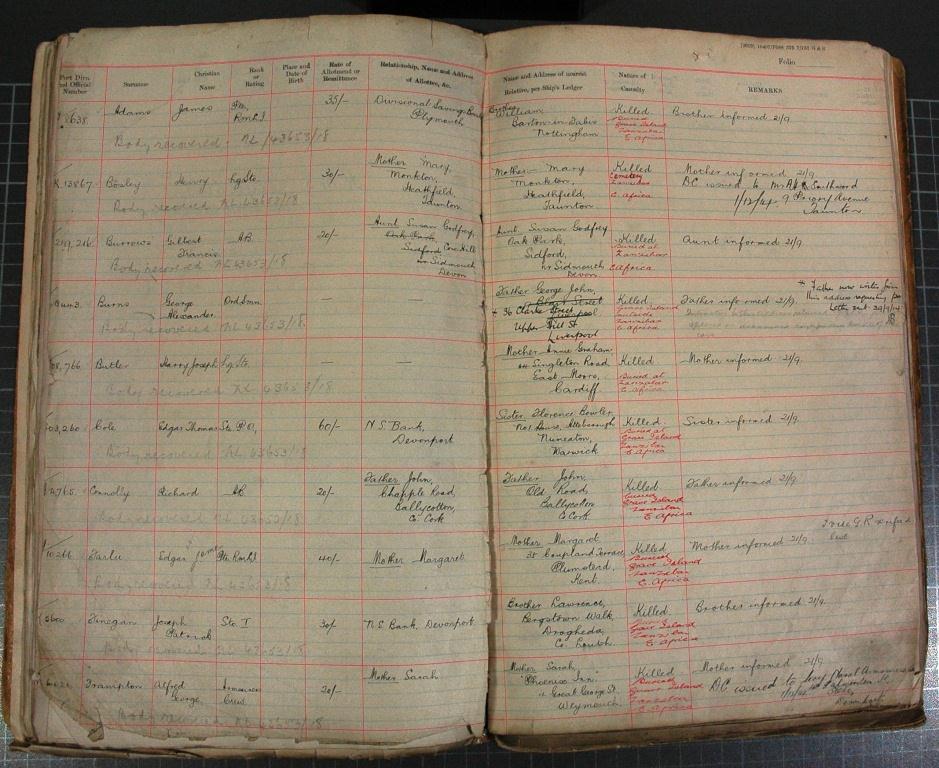

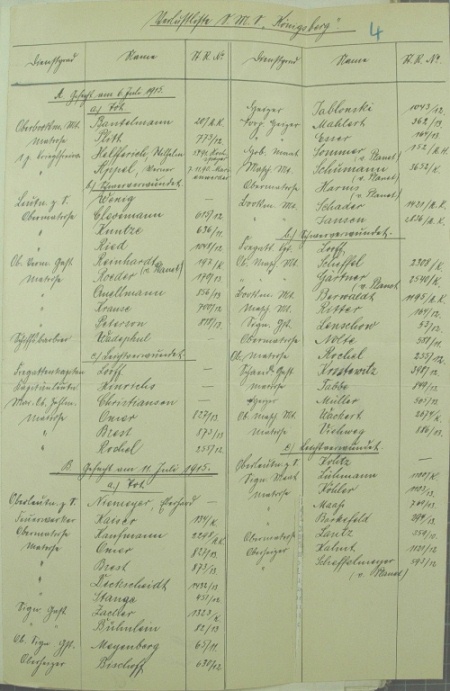

The end result of the Konigsberg’s attack was the loss of 38 crew and 55 wounded, though these numbers vary from source to source. The register records the number as 38 with 48 wounded, its cover 36 killed. Another list within the record has it as 38 killed, 51 wounded and four slightly wounded (ADM 1/8394/326 ).

List of men killed and wounded; record also contains correspondence from some family members (catalogue reference: ADM 1/8394/326)

Blockading the Rufigi delta

To keep the Konigsberg in the delta, an operation was launched on 10 November 1914 to sink the collier Newbridge across the main passage of the river. There were a number of vessels involved in offering covering fire from the very heavy fire being taken from the shore.

Correspondence shows that in the sinking of the ship, removal of the crew was carried out gallantly and successfully. There were casualties: Walter Fitzjohn and Timothy McCarthy, both leading seaman, were killed, and a number of ratings and officers wounded (ADM 1/8402/416).

- List of killed and wounded (catalogue reference: ADM 1/8427/192)

- Timothy McCarthy (catalogue reference: ADM 1/8402/416)

- Walter Fitzjohn (catalogue reference: ADM 1/8402/416)

- Jack George Ransom (catalogue reference: ADM 1/8427/192)

Then on the morning of 6 July 1915 the two monitors, Severn and Mersey, entered the Rufigi river and opened fire. Konigsberg replied immediately firing salvoes of five guns with accuracy and rapidity. HMS Mersey was hit twice: four men were killed and four wounded by one shell (ADM 1/8427/192).

A second operation was required and on 11 July the Konigsberg was finally destroyed.

Konigsberg destroyed but not conquered

ADM 137/4297 contains SMS Konigsberg reports, which is a collection of handwritten letters by Captain Looff, as well as other translated records. Within the record there is a list of dead and casualties that gives an indication to the German losses.

The memory of the losses to German, African and British personal are captured and recorded in the records and serve as a reminder to the true cost of war. 24 of the Pegasus crew were buried at Zanzibar (Grave Island) Cemetery, which the Commonwealth War Graves Commission maintain. Details of the cemetery can be found on their website: Zanzibar.

Thank you for a well written, concise account of the sinking of the Konigsbergberg.

The list of German casualties given as (catalogue reference: ADM 137/4297) is for me as an English speaking person, difficult to read.

Do you perhaps have a typed up version of the list?

Secondly, is there any indication in your files on the Konigsberg sinking, where the German sailors were buried?

Many Thanks