As the archive of medieval government and the law courts, our collections can shed light on official responses to pandemics, infection and disease, going back 700 years to the Black Death and beyond. As a historian who has worked on state responses to health and disease in pre-modern England, I have been taking a look at some of the first quarantine measures recorded in England, why they were implemented in 1517-18, and how they were received.

You can also find out more in my forthcoming online talk, Quarantine and Social distancing during Tudor epidemics, on Wednesday 17 June, where I will be exploring some of the stories and themes outlined here in more detail. Our full programme of online talks can be found here.

When we think of plague in England, two major epidemics come to mind: the ‘Black Death’ of 1348-49 and the ‘Great Plague’ of 1665-66 – two outbreaks among the centuries-long ‘Second Plague Pandemic’ caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis[ref]Of course, the current Covid-19 pandemic is not the same as the Black Death. Mortality rates, among many other factors, are completely different between the two diseases, and the world we live in is not the same world that medieval people would recognise (even if many aspects would be familiar).[/ref]. These were events of mass mortality, which would shock the population, but in the three centuries between these outbreaks, England would experience many smaller, regular, outbreaks which were no less dangerous for those who encountered them. Indeed, by the start of the 16th century, plague epidemics were an almost annual occurrence, increasingly made worse by outbreaks of sweating sickness and other infectious diseases from 1511.

My research, published in Social History of Medicine in 2019, explores the ways in which the state attempted to control and manage these regular outbreaks, and how people learned to live with the regular threat of infection (a link to this article is available at the end of this blog). In 1517-18 in particular, a new state measure was put in place for the first time in England, a measure brought about by the personal fears of the monarch: quarantine[ref]Such measures had been common in Italy and other southern European states since the 14th century, but their implementation in 1517 appears to have been in response to Henry VIII’s own very personal fears of infection, as well as a particularly dangerous outbreak of plague and sweating sickness throughout 1517-18. They were not the first quarantine measures in the British Isles, with measures recorded at Peebles from 1468, in Edinburgh in 1498, and similar measures to those later described in England from 1502 onwards, although these were largely locally produced measures, reinforced by royal support. Further details can be found in my article (linked to above), pp. 13-14 and Charles F Mullet, ‘Plague Policy in Scotland, 16th-17th Centuries, Osiris (1950).[/ref]. While fear of infectious disease was, of course, completely normal, Henry VIII was often described as having a particularly pronounced personal fear of infection, which may have been – in part – related to the deaths of family members in his youth, including his maternal grandmother, and possibly his elder brother[ref]Evidence from the Venetian ambassador’s accounts from 1511 suggest that Henry VIII was concerned then about disease, with a cryptic sentence suggesting that his fears derived from the death of his grandmother Elizabeth Woodville, some years earlier. This ties in with descriptions of Woodville’s funeral account, which was low-key and very much rushed, and indicates Henry’s historical fears of disease – not that Woodville had died in 1511. More information can be found in this article from the Guardian, this expanded blog by Joanna Laynesmith, which details some of the further points from my published article, and in the article itself. The images used in the Guardian article are not the original letters (located in Venice), but later transcripts, held in our collections at The National Archives. It has also been suggested by my colleague Sean Cunningham, among others, that Prince Arthur, Henry’s brother, might have died from infectious disease: Sean Cunningham, Prince Arthur (Stroud, 2016).[/ref].

Throughout 1517-18 (and indeed before this), the primary means of attempting to avoid infection was mobility. Henry’s court moved around the countryside frequently, often stopping for only short periods of time before departing to the next palace or residence. As well as for the royal court, mobility was the main defence for those wealthy enough to afford it, and the distances involved did not need to be great. Evidence from Eton College from 1510, for example, shows that the college travelled fewer than four miles when decamping in times of infection, from Eton to Langley in Slough[ref]Eton College Archives, MS Audit Roll 18.[/ref].

On occasion, however, even increased mobility of the household was not enough for Henry. On 6 August 1517, the King was recorded as having dismissed the entire court – both his own and the Queen’s – as the plague had made ‘great ravages in his household’, keeping behind only a few choice attendants: his physician, three favoured gentlemen, and the priest and musician Dionysius Memo.

A later Venetian dispatch on 11 November gives further perspective to Henry’s personal fear of epidemic disease and mortality. While the epidemic had made great ravages among the wider household, the King’s own chamber had been directly affected, and two of the pages who slept in his personal chamber had died.

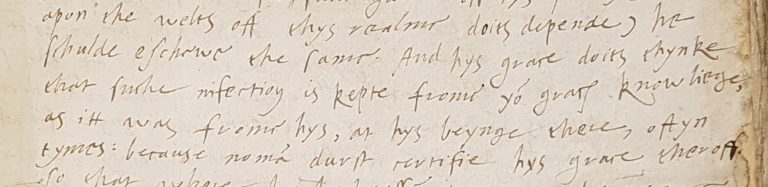

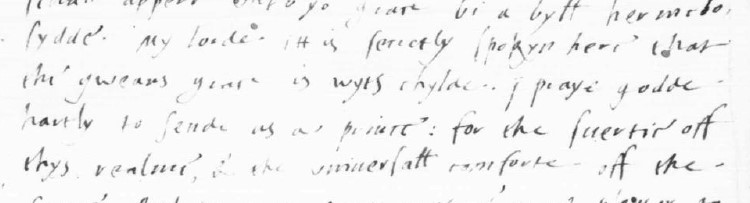

The king appears to have been particularly alert to rumours of infection around the country. There was a particular distrust of London, where Henry claimed that outbreaks had been kept secret from both the Chancellor, Thomas Wolsey, and himself, and so despite diplomatic unease at his departure, the king was unwilling to return to the capital (despite his lodgings having run out of supplies), stating in March 1518 that he was quite comfortable in Abingdon:

On this occasion there was a further concern on the king’s mind – Queen Katherine had become pregnant – the news of which would appear in correspondence a few days after his statement.

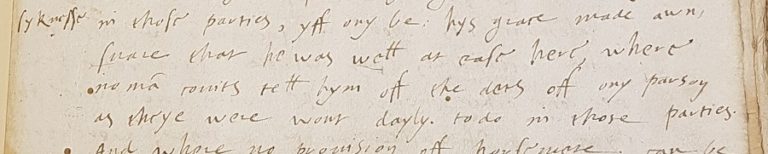

Throughout the epidemic, the king had one main aim: keeping himself and his royal lodgings free from infection, notably Windsor Castle. In particular, Henry saw St George’s Chapel as a weak point for infection in his castle’s defences, with many pilgrims travelling from afar to visit the chapel’s relics[ref]Which included the body of Henry VI (where miracles were said to take place), part of the true cross, and part of St George’s skull set in gold.[/ref]. As such, he wrote to the chapter of St George’s College in September 1517, as the threat of infection was rising, complaining that his castle had become infested with ‘contagious plague’, which the castle inhabitants had inadvertently helped to spread[ref]It is uncertain whether this relates to traditional plague or to a different disease such as the sweating sickness.[/ref]. He asked that the college produce a means of remedy, which they did in a set of quarantine ordinances later adopted around the country[ref]St George’s College Archives, Windsor Castle, IV.B.2.[/ref].

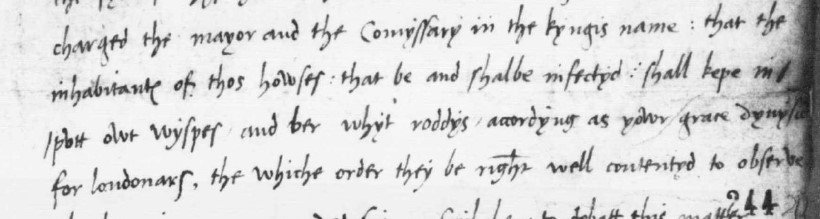

‘take special regard and make diligent search amongst you from time to time that there be no resort, sojourning, nor lodging of any strange persons within any of your houses in our said college which shall come from London or any other place where any infection is’

The first ‘state’ quarantine measures in England (1517): St George’s College Archives, Windsor, IV.B.2

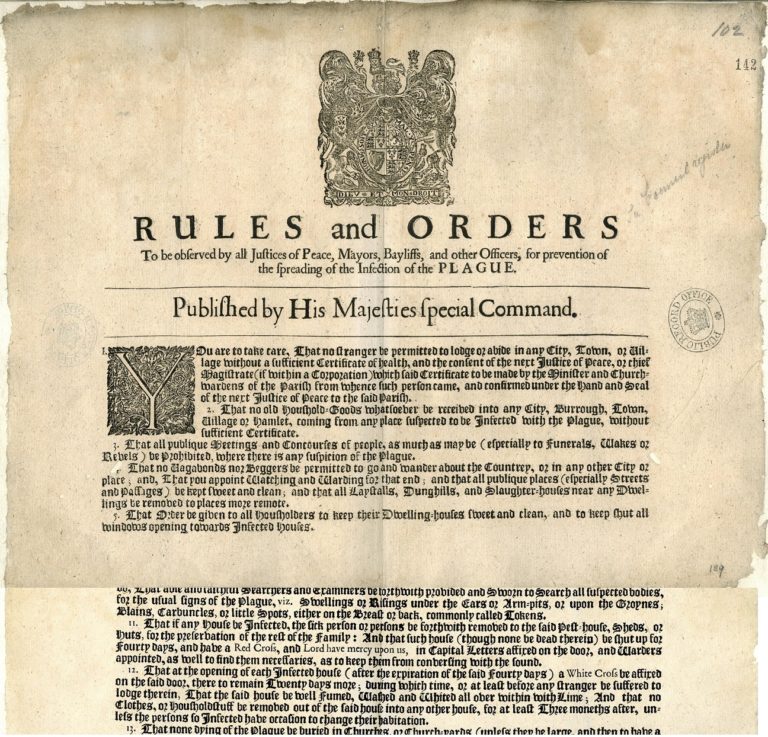

According to the college’s ordinances, produced in November 1517, and probably based on the French tradition – the canon-steward at this time had served as royal almoner to Henry VIII’s sister, Queen Mary of France during her short lived time as queen – strangers were to be sought out in times of plague, and were banned from lodging in the college[ref]The inspiration and individuals involved in the composition of these injunctions will be discussed further in the What’s Online talk to accompany this piece. This is also discussed in detail in my article (linked to above).[/ref]. This was particularly important if such a stranger was from London or from somewhere else where infection had spread. Any castle inhabitant who became infected was to be quarantined immediately and the door of the house was to be shut up, limiting access[ref]St George’s College Archives, Windsor Castle, IV.B.2.[/ref].

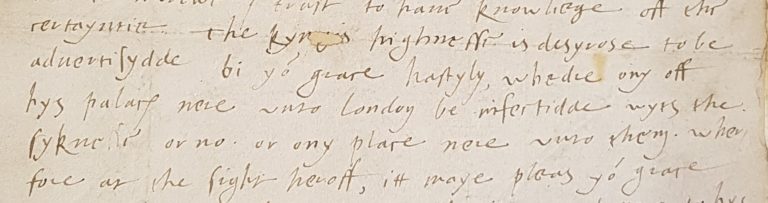

‘and in case any of you or yours be infected or shall fortune to be infected, that then ye do see the doors of the house to be shut up where the infection is or shall happen to be amongst you, and that no recourse of people be made there, nor none of the persons of the said house do go abroad but only one to bring in meat and drink and other necessaries for the persons within the said house, he bearing always openly upward a white rod in his hand of four foot long, during the space of forty days after the last infection within the said house, and also that a wisp of hay or straw be hanged out of the said house upon a pole’s end of eight foot long at the least’

The first ‘state’ quarantine measures in England (1517): St George’s College Archives, Windsor, IV.B.2

Access into and out of quarantined houses was strictly limited. One person only was permitted to leave the house, to fetch food, drink and other necessities. While out of quarantine they had to carry a four-foot-long white rod upright, so that other members of the castle community could maintain their distance and avoid the possibility of infection. A further pole, this time of eight foot or over, was to be fasted from the side of the quarantined house, with a wisp of hay or straw on the end, to warn the castle community of the infected house, and allowing them to maintain their distance. These provisions were to be continued for 40 days after the last sign of infection, so that the threat of further infection had passed.

It isn’t clear how effective these measures proved to be, or how the Tudors found their way through some of the practical problems (purchasing food supplies in the absence of home supermarket deliveries for example[ref]It is uncertain how such an individual was supposed to buy or receive the meat and drink without human interaction. Presumably provisions were left out for collection, although this was not explicitly stated.[/ref]), but they were soon copied in London and Oxford in 1518 by Wolsey and Thomas More respectively. In London, the measures were tweaked, presumably in an attempt to make them more effective, with a longer pole required (ten feet rather than eight), which must extend seven feet into the street. Furthermore, a bundle of straw was required at the end of the pole, rather than the wisp used at Windsor.

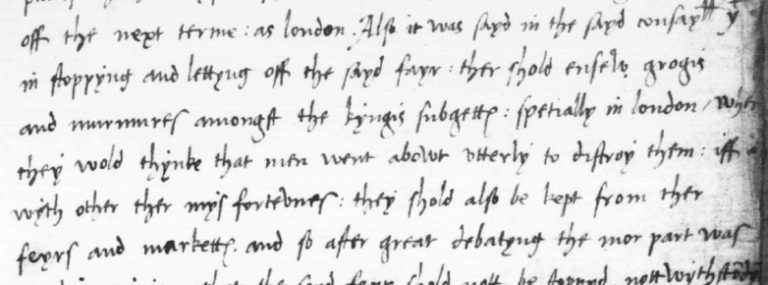

More’s implementation of quarantine measures at Oxford, however, was controversial, and became the subject of much debate among the King’s Council. While the measures taken by More were approved, the council were reluctant to cancel the annual Austin Friars’ fair, due to take place a fortnight later. Concerns over an influx into Oxford of infected persons from London were balanced against open hostility from certain merchants in London and Oxford, who felt the ordinances limited their mercantile activity.

In time, it would become clear that neither the Windsor nor London injunctions were sufficient themselves to prevent the spread of plague on their own. Infection continued to strike Windsor castle and surrounding areas, and mobility remained the remedy of choice. Over the course of the 16th and into the 17th centuries, regulations became increasingly more stringent, and often controversial, but the idea of quarantine would persist as one tool in the state’s responses to infectious disease.

This blog is based on research published as ‘’To Be Shut Up’: New Evidence for the Development of Quarantine Regulations in Early-Tudor England’, Social History of Medicine, currently available in Advance Access. Oxford University Press have kindly made this article freely available for a limited period to accompany my online talk, for three months from Wednesday 3 June 2020. A copy is also available in The National Archives’ library catalogue.

Further reading:

Carole Rawcliffe, Urban Bodies (Woodbridge, 2013) – Includes an appendix of all known national and urban epidemics in England between 1257 and 1530

Paul Slack, The Impact of Plague in Tudor and Stuart England (Oxford, 1990)

Various essays in The Fifteenth Century XII: Society in an age of plague, ed. by Linda Clark and Carole Rawcliffe (Woodbridge, 2013)

Euan Roger, ‘Preventing the Plague at St George’s’ (blog) [link here]

Joris Roosen and Monica H Green, ‘The Mother of All Pandemics: The State of Black Death Research in the Era of COVID-19 – Bibliography’ [link here]

Please note: We realise that some participants may have had trouble accessing the talks linked to in this blog. A replay of these events will be made available in due course, so if you keep your existing access link and code, you will be able to view it.

A high quality recording of this talk is now available on our website.

Euan’s article on this topic is available online for a limited time at:

https://academic.oup.com/shm/advance-article/doi/10.1093/shm/hkz031/5448886

Fascinating insights into quarantine procedures which are largely unchanged i.e. social distancing.

Great! An enlightening and relevant piece of history!

Sadly, I tried to get in several times but Flow would not work. Multiple browsers. Will this series be recorded and available on the web at some point? Thank you for your assistance in advance.

Hello Walter, sorry to hear you had problems accessing the talk. We hope to put a recording of this talk, with a transcription, on our website at Archives Media Player soon. Please check our social media for updates.

Euan, Thank you for today’s webinar, it provided a fascinating insight into the protection measures taken in Tudor times against the various plagues and illnesses. I really enjoyed it.

As a non-historian, I was amazed at the similarities to the policies of today. I particularly liked the long poles with wisps of straw on them. Perhaps we should try that idea. Thanks for an interesting talk.

Received my link, which worked but the code didn’t. Despite several attempts wasn’t able to access the talk. Only just mentioning now as I’ve been ill in hospital. Was gutted not to be able to access.

Hello Victoria, sorry to hear you had problems accessing the talk. We hope to put a recording of this talk, with a transcription, on our website at Archives Media Player in the next few weeks. In the meantime, you can access all of our previous talks on the media player. Please check our social media for further updates. Euan

I couldn’t get into the webinar on the day but have just listened to the recording. It was a fascinating insight into quarantine measures which are still implemented today. Fascinating history lesson too