Meet Constable John Napper, of Tintinhull in Somerset. You’ll find him a man of strong views, expressed with some energy.

‘I do not care a fart for this warrant’, he declared when the high sheriff’s man pressed him with his authority to collect King Charles’s latest revenue-raiser, Ship Money. With his boot, Napper pointed to a straw lying in the filth-strewn market place. ‘I care no more for the high sheriff [Henry Hodge] and his warrant than for that straw!'[ref]1. SP 16/291, f.57; Calendar of State Papers Domestic, Charles I, 1635, pp.145-6[/ref]

Sometimes, despite modern air-conditioning, the ripe whiff of an Ilchester market day may waft into The National Archives on a 380-year-old breeze; a raucous snatch of Somerset voices may drift down the stairs to the Staff Reading Room. But I did nearly miss out on an acquaintance with the charming Constable Napper.

I’m glad the Early Modern Team asked me to join their PC 2 project – cataloguing the Privy Council registers for the decade before the Civil War – but initially, I wasn’t sure.

The curly handwriting in those massive, leather-bound tomes was intriguing and elegant, but it looked mighty hard to untangle. Besides, I knew next to nothing about the 1630s… apart from, perhaps, Constable Napper’s bug-bear, Ship Money.

A few clichés

Here are some of the things I thought I knew about Ship Money:

- Charles only had the nerve to introduce it because he was a tyrant

- It was an illegal tax, because it was not endorsed by parliament

- Its revenues kept the king from bankruptcy

- It produced a wasteful expansion in a fleet which never saw action

- It was eventually discontinued because of popular agitation against it

- It was one of the key irritants leading to the outbreak of the Civil War.

However, after two years on the project it turns out that some of these ‘facts’ retain little more than a kernel of the truth.

Ship Money

Calling on the nation’s sea-ports to defend against a sea-born threat by chipping-in with Ship Money was nothing new, but several aspects of the way King Charles went about it were novel.

For one thing, when he first set out to raise Ship Money in 1634 it was the first ever demand in peace-time. Then, when writs were issued in 1635 they were sent to inland counties as well as coastal ones. By 1636 it was becoming clear to everybody that the measure was intended not as an emergency measure but as an annual source of revenue.

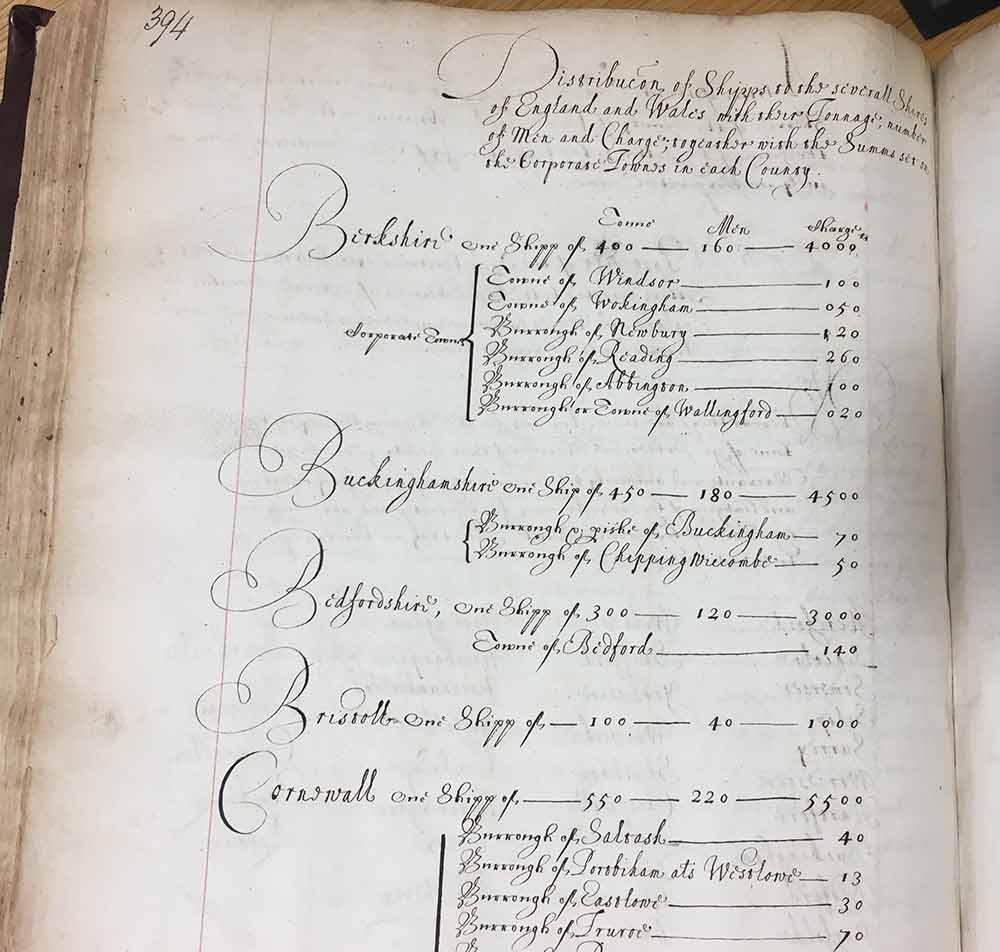

In theory, Ship Money was not a tax, but a demand for physical warships. Each county was to provide one – two in the case of London – and the writs required the specified vessel to be available for service, at Portsmouth, by 1 March of the next year.

For example, the county of Berkshire was required to supply, provision and victual a ship of 400 tons and 160 men to crew it for six months. Or a monetary equivalent could be paid. In Berkshire’s case this was £4,000.

In practice, though, few actual ships were provided in this way, although London did provide one.[ref]2. Sharpe, Kevin, The Personal Rule of Charles I, p.553[/ref] Just about every entry in the Privy Council registers relating to ‘the business of shipping’ is expressed in pounds, shillings and pence.

Table of Ship Money assessments for each of the counties of England and Wales from the Privy Council Register, 1636 (catalogue reference: PC 2/46, p.394)

Legality

If this demand for warships was a bit of a fiction, it was a cleverly authored one: it meant Ship Money was not a tax and didn’t have to be approved by parliament. It was a service which the nation’s subjects were obliged to provide for the defence of the realm. Payment was made directly to the Treasurer of the Navy, not to the Exchequer.

This argument was heavily relied on when Ship Money was brought to court, with the crown prosecuting Buckinghamshire land-owner, John Hampden. In this key test-case, the legality of Ship Money was narrowly upheld.

Can’t pay, won’t pay!

The Hampden case was the culmination of a growing disgust over Ship Money.

From all corners of England and Wales petitions were directed to the Privy Council, arguing for every obscure point of law, precedent or privilege. Mayors and burgesses, the clergy, landowners large and small, coal-miners, warrant-holders; everybody reckoned he was paying too much, or he shouldn’t have to pay at all.

A common tactic was to try to pay where the levy was lowest. Sir Robert Phelips was a big man in Somerset, a die-hard opponent of Ship Money, and the power behind our friend, Constable Napper.

Petitioning the Privy Council, Sir Robert successfully claimed he ought to be paying the levy for his Northover estate as part of Ilchester’s assessment (£30), not that of the hundred of Tintinhull (£130 assessed).

In their turn, that left a heavier burden on the levy-payers of Tintinhull, who counter-petitioned.[ref]3. Calendar of State Papers Domestic, Charles I, 21 and 25 Nov 1635, p.495 & p.502[/ref]

Some levy-payers objected in principle. Richard Powell, vicar of Pattishall, Northamptonshire, preached a sermon about ‘cruel and unjust’ taxes, following which his parishioners refused to pay their Ship Money. He was hauled up to London to explain himself to the Privy Council.[ref]4. PC 2/48, pp.609-10; PC 2/49, p.15; Calendar of State Papers Domestic, Charles I, Feb 1638, p 285[/ref]

Send in the bailiffs

Across the country bailiffs were sent in to seize goods from non-payers to the value of their Ship Money levies; the determined reception some received gives us a flavour of how incendiary a sermon such as Powell’s could be.

In Long Buckby, bailiffs faced ‘a great number of women, boys and children with pitchforks, and their aprons full of stones, to the number of three-score at least … and the next day people did rise in rebellion with forks and staves … saying knock them down, beat out their brains, hang them, rogues.'[ref]5. Langelüddecke, Henrik, ‘”I finde all men & my officers all soe unwilling” : The Collection of Ship Money, 1635-1640’, Journal of British Studies, Vol 46, No 3 (July 2007), pp 509-542, citing SP 16/379, f 132[/ref]

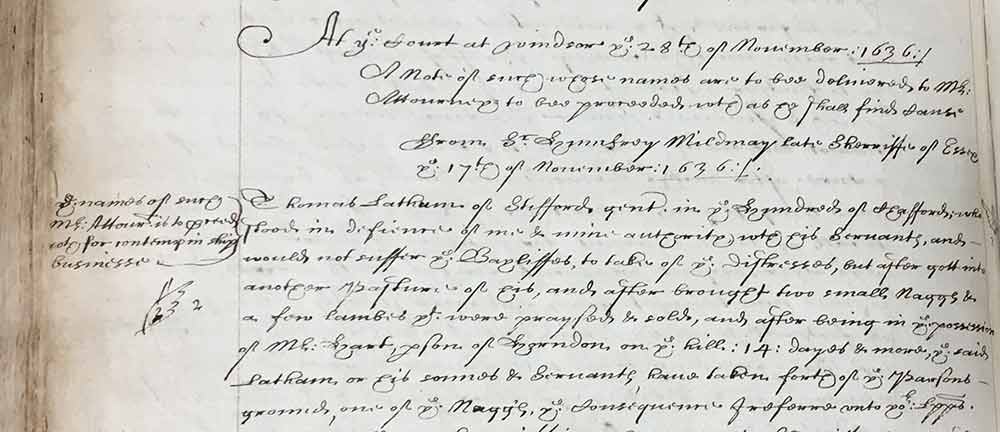

Elsewhere, opposition was less violent, but determined, nonetheless. In Essex, when bailiffs seized and sold Thomas Lathum’s horse, he simply took it back.

Ship Money defaulters were obviously an awkward lot, and seizing their goods and livestock was a considerable undertaking. Sir Robert Pointz, high sheriff of Gloucestershire, warned that ‘there will not be found prisons and penfolds enough in the county to receive them’.[ref]6. Calendar of State Papers Domestic, Charles I, March 1638, p 337[/ref]

Who’d be a High Sheriff?

Not many wanted to undertake the arduous, year-long duties of high sheriff. Shaking out their neighbours’ pockets can’t have made sheriffs popular locally. Then they got it in the neck from Whitehall.

In July 1637, the Privy Council sent a letter admonishing high sheriffs in two-in-three of the counties for their ‘slackness and remissness’ in collecting Ship Money.[ref]7. PC 2/48, p 136[/ref]

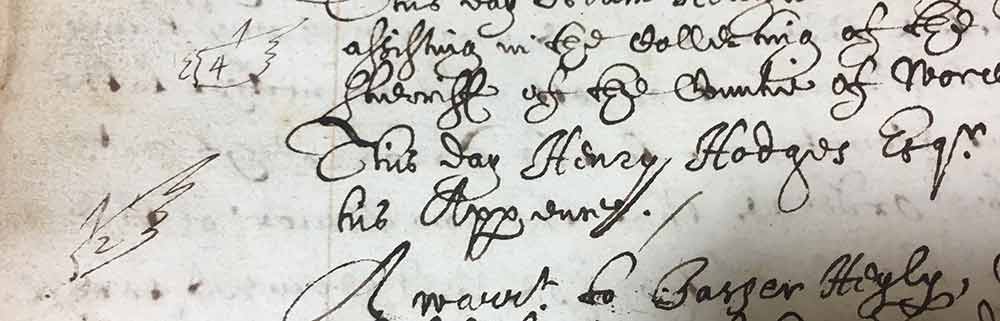

Manicule, or pointing-hand sign, ‘2’, indicating that the Privy Council on 3 February 1639 was still at odds with Henry Hodges over Ship Money for 1635. ‘1’ indicates 1634, ‘2’ for 1635, ‘3’ for 1636 and so on (catalogue reference: PC 2/50, p.74)

Year on year, arrears mounted. Typically, sheriffs would blame their predecessors, and the constable, bailiffs and parish officials who they said wouldn’t cooperate. ‘I finde all men and my officers all so unwilling’, lamented the high sheriff of Sussex and Surrey. [ref]8. SP 16/329, no 37; Langelüddecke, p 512[/ref]

For all the sound and fury, nearly all the Ship Money did come in. True, passions were aroused, but often this illustrated local rivalries as much as, or more than, opposition to the crown revenue-raising. Among our Somerset acquaintances, Sir Robert Phelips found Ship Money a useful stick with which to bludgeon the hapless High Sheriff Henry Hodges, and he set about the business with enthusiasm.

Also, Richard Powell’s contentious sermon, although picked up in London as anti-Ship Money, may have had more to do with disagreement among parishioners over proper forms of worship, than about crown privilege.

New thoughts

So, here are some things I now think I know about Ship Money. Firstly, the legality of Ship Money remains a moot point.

It’s true the Ship Money fleets never waged war but, during an age when conflict convulsed much of continental Europe, the passivity of the fleet might be viewed as a triumph of deterrence.

As a tax, Ship Money was not a failure and collection rates were high. One historian has called it ‘the most successful extraordinary tax in early modern (perhaps modern) British history’. [ref]9. Sharpe, p 558[/ref]

Ship Money did not fill Charles I’s empty coffers and stave off bankruptcy. The additional revenues raised, about £200,000 per year, did not even fully fund the navy. [ref]10. Sharpe, p 594[/ref]

There was popular anger over Ship Money, but the main rock which sunk Ship Money was a new focus on land-defences arising from the Bishop’s War in Scotland. [ref]11. Langelüddecke, p 529[/ref]

A volunteer’s personal statement

And now, a confession. We’ve been seeing each other now, for the past two years, and he’s grown on me. As I’ve leafed slowly through the pages of the Privy Council Registers (and I can now read the council clerk’s writing) I’ve learned to love Charles I.

Busy with his Privy Councillors, he seems a much more sympathetic, more collaborative, more conciliatory character than I imagined the sovereign of the ‘Personal Rule’

My modern eye is struck by how few levers his government had available to it. Influence, persuasion and persistence brought Ship Money tinkling in to the Navy coffers, not brute force.

I wish I could tell you that any trouble our friend Constable Napper got into was forgiven him, but I don’t have the evidence. What I can say is that most who were called up to London over Ship Money were sent home again after promising to pay.

Even Sir Robert Phelips, who had been shown to have ‘disrupted’ high sheriff Henry Hodges in his efforts to collect Ship Money, was found to have ‘done nothing in the service of shipping than what had become a good subject and a well-affected person of this country.'[ref]12. Calendar of State Papers Domestic, Charles I, 1635, p 502[/ref]

And rabble-rousing Richard Powell? Neither his ‘many scandalous indecencies and profanations arising out of drunkenness’, nor his ill-advised sermon on unjust taxes seem to have debarred him from a successful career in the church.

Questions

So, I’ve learned a lot from PC 2 about Ship Money but I still have lots of questions. How many actual ships were provided rather than payments in lieu? Was the ship set up by London the only one? Were ships newly-built, or did counties lease them? What role did the King’s own ships play?

Answers on a blog post please.

Excellent presentation! Well organized questions answered directly. Historians should follow this discussion as a pattern for their writing. I Googled the topic directly after reading about Ship Money in Mark Kishlansky’s “A Monarchy Transformed.” I wondered if collection rolls existed? Apparently not, at least not in the National Archives, since collection was by county assessment. Now I’m wondering if any county kept rolls? Could the Ship Tax have been another inducement to emigrate to North America?

A really useful article – I found my research subject, a Gloucestershire MP, had, according to the Victoria County History been imprisoned twice when he refused to pay ship money and wondered where this put him politically.

Alison Gill’s 1991 Sheffield University Ph.D. thesis on Ship Money clearly shows that the levy met increasing resistance in the late-1630s (after Hampden’s case) and that it was not successfully collected.