Last year I wrote a series of blogs based on the criminal petitions in record series HO 17, which is currently being catalogued by a team of volunteers. In petitioning the Home Office, criminals, their families and supporters were often seeking a mitigation of their punishment. There are also petitions from those who tried to join their loved ones in exile, in various ways and with varying degrees of success – the focus of this blog.

In petitions seeking mitigation, personal circumstances were frequently cited to demonstrate factors like the convict’s good character, their innocence, that they were seduced into crime by others, or driven by desperate circumstances; perhaps they were too old, sick, young or insane to be sent overseas or remain in prison. A commonly made plea is that the convict’s transportation will leave their families destitute: without their income, the convict’s family, be they elderly parents or a young wife and children, will be forced on to parish relief.

But faced with the misery of separation from their loved ones, and potential destitution from the loss of their income, we also find many petitions from those seeking to join family members in New South Wales or Van Diemen’s Land. Most of these petitions are from wives, many of them wishing to travel with their children to join their husbands in exile, although there are also examples of convicts requesting that if they have to be transported their families be allowed to accompany them.[ref] 1. The vast majority of transportees were male – in ‘The Fatal Shore’ Robert Hughes estimates that when transportation to Australia was at its peak, between 1831 and 1841, a rounded figure of roughly 43,500 male and 7,700 female convicts sailed for Australia. (p.162) [/ref]

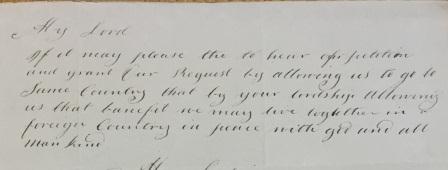

In 1835 Margaret Tobin of Cork wrote to the Home Office seeking assistance to join her husband James in New South Wales (HO 17/32/142). James had been convicted in 1829 and an initial sentence of death had been commuted to transportation for life. In her petition Margaret outlined her efforts to provide for her family in James’ absence: ‘for the last six years she has been struggling without the help of any in procuring the common necessaries of life for herself and helpless children.’

As her children grew older Margaret felt she was unable to provide for them as her husband might, and so:

‘it would be her anxious desire to migrate to her bosom friend in whose power it is at present to afford all consolation, and to give to his offspring the means of earning their bread which he himself useth, which is in dressing leather’.

Interestingly Margaret knows of another convict – ‘one of the sufferers with her husband’ – whose wife and child were provided with passage to join him. Sadly for Margaret and her children, her petition is annotated ‘Nil’, suggesting they did not have such a happy resolution to their case.

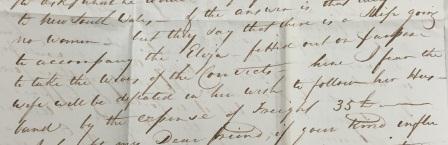

As Margaret discovered, many applications for passage to Australia were refused, and to pay for one’s own passage could be impossibly expensive for those who were already in financial difficulty.[ref] 2. In ‘Convicts and the Colonies’ Shaw estimates that the granting of free passage to the wives and children of transported convicts involved an average of only 200 per year in the 1830s (p.229).[/ref] In a petition on behalf of George Myland, who was sentenced to 14 years’ transportation in 1830, we learn that his wife is deeply distressed and desperate to join him in New South Wales. A family friend has learnt that a ship has been fitted out for the wives of convicts to accompany her husband’s transport the Eliza, but the £35 charged for passage was beyond her means:

‘I fear the wife will be defeated in her wish to follow her Husband by the expense of freight 35£.’ (HO 17/54/91)

In 1833 Elizabeth Lewis sought to raise money to fund her passage to New South Wales. Her husband Thomas had been sentenced to transportation for life and she wrote to the Home Office requesting that she may be able to claim any money owed by his debtors. A scribbled ‘nil’ on her petition suggests that this enterprising suggestion was also unsuccessful (HO 17/37/29).

Some petitions received support from parish officials or local communities mindful of the financial burden that single mothers and their children might place on the parish or local Poor Law Union. Charles Chambers was convicted of sheep stealing in 1828 and following the reduction of his initial death sentence to one of transportation for life, he was sent to New South Wales. In a series of petitions his wife Lucy, supported by the local community, pleads for a reduction of his sentence on the basis that his transportation leaves Lucy and their three children destitute. In 1838 she writes to the Home Office expressing her thanks for being granted a passage for her and her children to join Charles (HO 17/53/238).

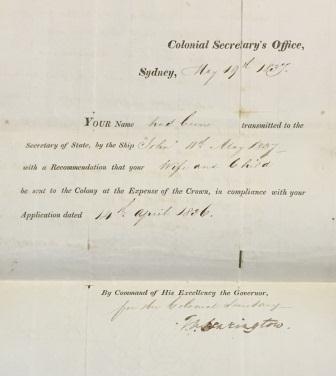

Permission for John Booth’s family to join him in New South Wales (catalogue reference: HO 17/52/137)

However, even where permission was granted and passage secured, family reunions did not always come off. In May 1837 John Booth received permission that his wife and child might join him in New South Wales at the expense of the Crown. John was sent to New South Wales in 1828 aged 22, having been convicted of burglary and sentenced to transportation for life (HO 17/52/137). The papers accompanying Booth’s case in HO 17 include a copy of the permission granted by the Colonial Secretary in Sydney for Booth’s family to travel, but a letter of February 1838 reveals that the happy reunion had not come to pass and a friend of the family petitions instead for John’s return. He reports that Mary has suffered greatly through John’s transportation and her health was now too delicate for her to undertake the journey.

One way in which families might try to reunite once in Australia was for wives to apply to have their family members assigned to them as convict labour. In September 1833 Mary Jarman wrote to the Home Office complaining that she travelled to New South Wales with her infant children on the expectation of her husband George being assigned to her, but on her arrival she discovered that George had been sent to Port Macquarie (HO 17/95/141). This practice was much restricted in 1826 when regulations were issued stating that:

‘No convict will be assigned on arrival to his or her wife or husband, or to his or her relation, or to any person applying for a particular individual. The ends of justice would be defeated by such assignment, and evil consequences could hardly fail to result from it. This indulgence will be reserved as the reward of good conduct. When any prisoner shall have proved himself of deserving of it, his claim will be immediately attended to immediately.’ (CO 201/184)

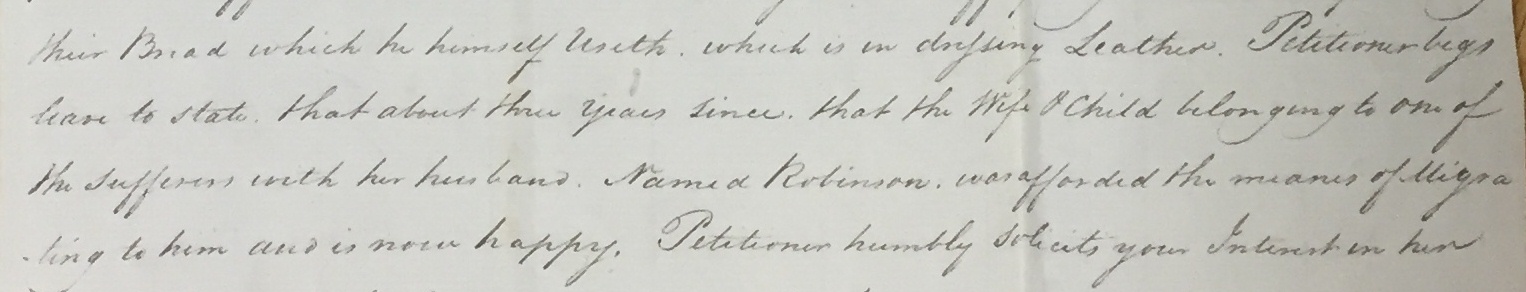

The Home Office was equally keen to ensure ‘the ends of justice’ were not jeopardised by a different kind of reunion: convict spouses reuniting in the colony. Husband and wife Jane and John Drew were convicted in 1836 for coining and were both sentenced to transportation for life. In a joint petition written shortly after their conviction they plead to be sent to the same country so that ‘we may live together in a foreign country in peace with God and all mankind.’ (HO 17/52/36)

Extract from John and Jane Drew’s petition (catalogue reference: HO 17/52/36)

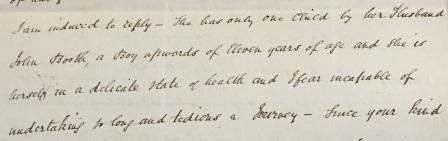

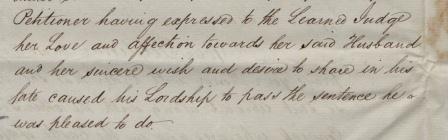

The potentially dangerous precedents which might be set by agreeing to such requests are explored in our final case. Jane Hardy was convicted in July 1822 for attempting to help her husband John escape from York Castle Gaol, where he was under sentence of death (subsequently commuted to transportation). In his report on the case, William Stanley of York Castle, notes that Jane was pleased to receive her sentence of seven years transportation, expressing her hope that it would be carried out so that she might join her husband in New South Wales and ‘share in his fate’ (HO 17/122/9).

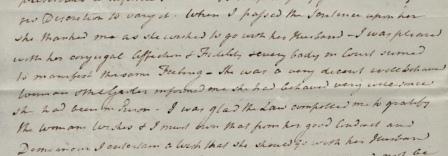

A Home Office annotation notes that ‘She must go to the Penitentiary’ but the presiding judge admits in his report that he was touched by Jane’s expression of ‘conjugal affection and fidelity’. He was in fact pleased to pass the sentence that would allow her to be reunited with her husband.

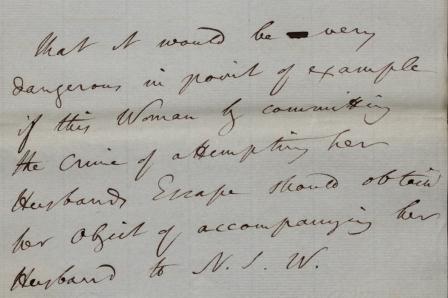

As a compromise he suggests she be sent to the Penitentiary for a time before being transported, for fear that she might ‘turn to bad courses’ if she was simply released in England. The Home Office remained unconvinced noting:

‘that it would be very dangerous in point of example if this Woman by committing the crime of attempting her Husband’s Escape should obtain her object by accompanying her husband to [New South Wales].’

In our cataloguing of HO 17 we see countless petitions stressing the poverty and distress of the family left behind by transportation. It has been an interesting, if sobering, experience to take a closer look at how families tried to reunite across what might have felt an impossible distance. It is thanks to the detailed cataloguing of our volunteers that we can undertake such research and search Discovery, our catalogue, using terms like ‘accompany’, ‘join’ or ‘free passage’ to track down these cases. [ref] 3. Although the focus of this blog has been HO 17, it is worth mentioning that we have hundreds more such petitions from convicts’ wives and families seeking passage to Australia among the Privy Council papers in PC 1/67-92. [/ref]

In addition there are almost certainly a number of records amongst the Treasury Board Papers (T 1) which are unindexed, but can be found by the indexes in T 2, T 4 and T 108.

Are there any cases of ‘petitions’ from a husband pleading to join a wife following a Transportation sentence?

I would also like to know of petitions from husbands to travel with their convicted wives. My ancestor Isabella Tyson arrived in NSW in 1809 and with her was her husband, William Tyson, and her second child (also named William Tyson) who was a baby.

Their 7th child, James Tyson, became Australia’s first millionaire by providing a butchery service to prospectors on the gold fields in the 1850/60s .