William Shakespeare’s signature on his will

As head of legal records at The National Archives, I’ve been looking in detail at one of our treasures: Shakespeare’s original will, full of amendments, which was left in the probate court by his executor.

Shakespeare’s will was first discussed in 1747 by the Stratford antiquarian Joseph Greene. He was disappointed by it, as has been almost every other commentator since. It seems an oddly unfeeling and unsympathetic document, and is often interpreted as proof of the unsatisfactory nature of Shakespeare’s character, his last years and family life.

I’ve come to two new conclusions, which are important for our knowledge of Shakespeare and his family:

- I have redated parts of the 1616 will to three years earlier, with implications for how we understand Shakespeare’s last years.

- I have placed in context those parts of his will which are cited as evidence that he was unkind towards his family, and offer a new interpretation of Shakespeare’s intentions.

Handling the will

In 2013, the artist Anna Brass made two films about Shakespeare’s will for us.[ref]1. The films are freely available: the first is This Holy Shrine and the second is Backwards Divination.[/ref] We looked at his original will, but – like everyone else – were not allowed to handle it. So Anna recreated the original will from a digital image, printing it full size in A3 and in colour, trimming it back to the ragged edges of the original paper, and folding it along its old fold-lines.

Carrying the facsimile around, I read it and reread it, examined the layout and the alterations, considered the different shades of ink, and created a new transcription.

And gradually I came to think that perhaps the accepted date and interpretation could be wrong.

Redating the will

Easter was early in 1616, falling on 31 March. It was a hard time for the Shakespeare family. On 25 March William Shakespeare, apparently ill, revised his will. The next day his new son-in-law, Thomas Quiney, confessed in church to fathering a child with another woman. In the next month, the family suffered two deaths: his brother-in-law on 17 April, and William Shakespeare himself on 23 April.

In late June, John Hall (William’s other son-in-law and joint executor) travelled to London with the original will to get a grant of probate. The probate court made a copy for John to take back to Stratford-upon-Avon, as authority to collect debts and distribute bequests, but kept the original to make an official copy in the register of wills. [ref]2. The registered copy is TNA: PROB 11/127/771. The original is TNA: PROB 1/4.[/ref]

Both copies accepted the changes written throughout the original, creating the impression of one smooth text. But the original will, with all its amendments, gives us a glimpse of Shakespeare in action.

The original three-page will is dated 25 January 1616, with January crossed out and replaced by March. A common view is that a new page one, altered from the old, was written in March (with January initially copied by mistake).

I’m adding another date to the mix: April 1613. I have identified page two as a page reused from a previously unknown will, written probably three years earlier when Shakespeare invested in a substantial London property, the Blackfriars Gatehouse.

I also argue that the other two pages were rewritten in January 1616, and that all three pages were slightly amended in dark ink in March 1616.

New technical analysis

The National Archives recently undertook a major new conservation of the original will; it is now much closer to its original state. Due to this conservation work and new technical analysis, we can see that the paper and ink of the three folios are not uniform, and show potentially significant differences.

We carried out multispectral analysis of the will at the British Library in January 2016. Multispectral imaging can indicate differences in the inks being analysed: those of a similar composition will only appear under certain wavelengths of light. The will was photographed under 13 wavelengths and under different filters and lighting.

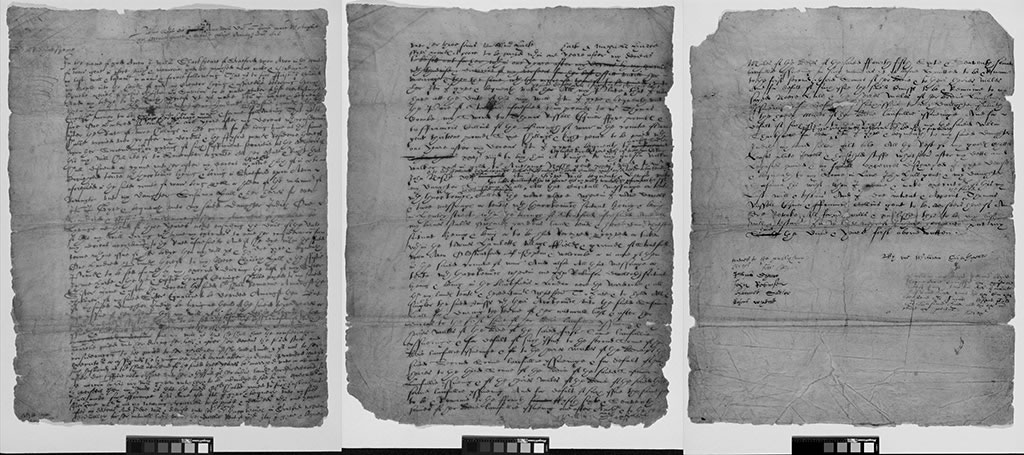

Shakespeare’s will as seen by the human eye (470nm spectrum) – all text is visible on all three pages (Crown Copyright The National Archives, Image created by the British Library Board)

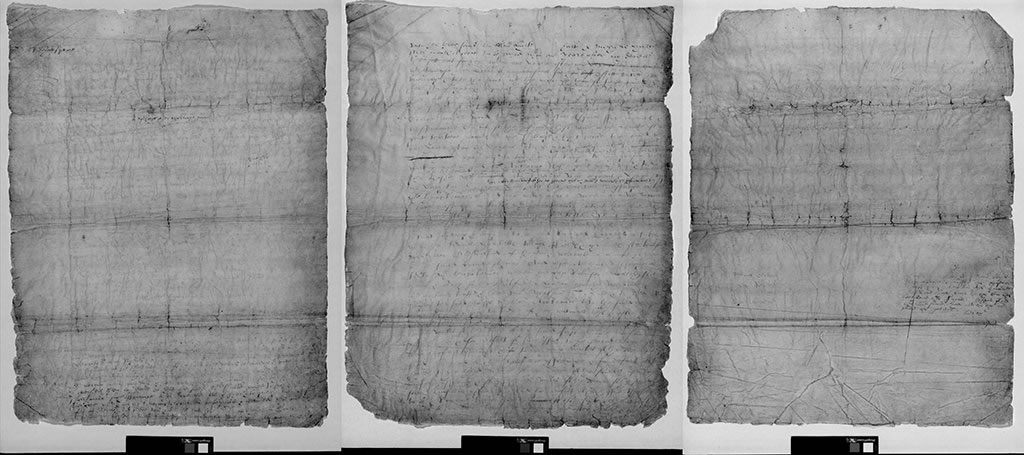

The images show that the ink used for the main body of text on the first page looks more similar to the ink on the third page than that on page two. So we have pages one and three possibly written with the same ink, and page two – my proposed 1613 page – on a different paper with different ink. Another ink was used for additions across the pages, which I dated to March 1616.

Shakespeare’s will under infrared rays (1050nm spectrum) – most text has faded away (Crown Copyright The National Archives, Image created by the British Library Board)

Rethinking Shakespeare’s last months

Redating the will could transform our ideas of the end of Shakespeare’s life.

It is often thought that people only wrote wills when they thought they were on their deathbed. It requires considerable speculation to fit Shakespeare’s will into this scenario, leading to claims that:

- Because he wrote a will in January 1616, he must have been expecting to die; as he survived until March, his illness must have been chronic.

- He was therefore probably suffering for a long time before January.

- He retired unwillingly to Stratford to be looked after because of this illness.

I think that Shakespeare was not seriously or chronically ill, nor expecting to die, in January 1616.

People wrote wills at different times for different purposes. Shakespeare may have written a will in early 1613 for two reasons. His last surviving brother had died unmarried in February 1613, altering Shakespeare’s options. And in March 1613 he invested in a large property in London, the Blackfriars Gatehouse, which was held in trust (probably for ease of resale). The trustees needed written direction for the future – in this case, a will directing that this property should go to Susanna Hall, his elder daughter. [ref]3. The terms of the will are cited in the indenture of 10 February 1618, which transferred the property to a new set of trustees (from the London-based John Jackson, John Heminges and William Johnson to the Stratford-based John Green and Mathew Morrys: Folger Shakespeare Library MS Z.c.22 (45))[/ref]

The existence of the 1613 will indicates long-term financial planning by Shakespeare with the help of his lawyer and friend Francis Collins. He adapted the settlement of his estates as circumstances changed, and he may have been doing this for years, as his property portfolio grew.

Why did he rewrite his will in January 1616?

Shakespeare’s younger daughter Judith was about to get married to Thomas Quiney, on 10 February: he was responding as a prudent and well-off parent to provide her with long-term financial security. The new first page is mostly about providing for Judith – her marriage portion of £100, a further £50, and another £150 to either go direct to her husband if he spends £100 to provide for her if he died, or to go to trustees to provide her with an annual pension if he didn’t do this.

The original top lines of page two were crossed through – they referred to Judith possibly getting married at some future date – but the rest of the page dealt with Susanna, and still stood.

Page three was rewritten because it contained the signatures of witnesses, which would need to be retaken.

What happened in March 1616?

It has been a common view that the entire first page was rewritten in March to make Judith’s provision more secure against her husband.

In this interpretation, Shakespeare’s state was worsened when his new son-in-law Thomas Quiney was accused in March of fathering an illegitimate child. He roused himself on his sickbed to write Thomas out of the will on 25 March.

My view on this? First of all, these provisions for Judith weren’t changed in March. These are January provisions for the immediate future of her February marriage, but also for any number of potential futures. Judith could die, with or without children. Her husband could die, and she might remarry. Her first or future husband could provide for her widowhood, but if he did not, her father would.

All this has often been misunderstood as grudging to Judith and mistrustful of her husband, when really it is a father trying to protect his daughter beyond his own death. Thomas Quiney’s own family showed the need for this kind of forethought: his father had been killed in 1602 leaving a widow and children.

In late March however, I think Shakespeare did get seriously ill quite suddenly. A small number of additions in a darker ink were inserted into the will at this point, including the change from January to March. These were the bequests of mourning rings to his friends in London and Stratford, and the bed to his wife. So at this point he thought he was ill enough to die, and probably deteriorated over the next four weeks.

The Stratford story about Shakespeare’s death, current in the early 1660s, was that he died of a fever contracted after drinking with his fellow playwrights Michael Drayton and Ben Jonson. Often dismissed, maybe this needs to be thought about again. A typical death from fever, with delirium and coma, would have meant there was little opportunity to add anything more to his will as Shakespeare got progressively sicker.[ref]4. The ‘typhoid state’ occurs classically with typhoid and typhus fevers but is also seen in other infectious diseases. Clinical descriptions of this state as ‘muttering delirium’ or ‘coma vigil’ refer to the peculiar preoccupied nature of the stupor. Picking at the bedclothes and at imaginary objects … are characteristic, as is muscular twitching… There is strong evidence that the death of Falstaff in Shakespeare’s Henry V is a vivid description of the typhoid state’: A [Abraham] Verghese, ‘The “typhoid state” revisited’, American Journal of Medicine 1985 Sep;79 (3):370-2.[/ref]

Did Shakespeare hate his family?

A general (but not unanimous) view is that Shakespeare’s will shows him to have been sour, unemotional and unkind, with a dysfunctional family. From this much more has been extrapolated:

- Judith was resented for out-living her twin brother Hamnet. She was probably uncared-for, unlike his elder daughter Susanna Hall – his favourite, and the lucky recipient of his wealth.

- Shakespeare made no provision for his wife Anne, except for the slighting bequest of the second-best bed.

- He had probably lost affection or respect for Anne years ago, if he ever had any – after all, she was older than him and pregnant when they married. No wonder he had abandoned his wife and three children to live in London.

But the will was written as a business document, about a future transfer of property to come into effect on his death. It was not a deathbed declaration, and was no place for expressions of affection. Sourness or coldness can’t be read into the formal language of such a document.

What can be inferred by looking at the bequests of rings for his friends and the bed for his wife, added in March 1616, was that when seriously and suddenly ill Shakespeare wanted to give personal mementos to people who mattered to him. These are tokens of affection from a man facing the prospect of his death.

What did Shakespeare intend in his will?

Much of the current understanding of Shakespeare’s will comes from not just confusion about its date, but also misunderstanding the contemporary legal background. After intense discussions with David Foster (a PhD student in legal history at The National Archives), more background can be sketched in here.[ref]5. Any misunderstandings here are my own.[/ref]

The vast complexities and sophistication of 16th- and 17th-century law and litigation are still daunting for researchers (quite understandably). Yet there are excellent guides to light the way. In particular, Amy Erickson and Tim Stretton, looking at women defending their rights in the courts of Chancery and Requests, make it clear that at this time there were standard methods to protect daughters on marriage and wives on being widowed.[ref]6. Amy Erickson, ‘Women and Property in Early Modern England’ (1993); Tim Stretton, ‘Women Waging Law in Elizabethan England’ (1998). See also Lloyd Bonfield, ‘Devising, Dying and Dispute: Probate Litigation in Early Modern England (2012) and H J Habakkuk, Marriage, Debt and the Estates System: English landownership 1650-1950’ (1994), for later developments. For a good recent overview, see Tim Stretton and Krista Kesselring, ‘Married Women and the Law’ (2013).[/ref]

Shakespeare’s intentions in his will need to be judged against this background. How could a man with no male heir, two daughters and a wife who might outlive him, provide them all with security and yet safeguard the family’s hard-won social status?

It looks as though Shakespeare was a provident man with a sense of familial ambition: having gained the landed estates needed as a gentleman, he wanted them to stay united as a patrimony in the family. Without a will, the usual rule of inheritance if a man had daughters but no son, was to treat them as joint or co-heirs, splitting the inheritance of land equally. However, ‘usual rules’ were often variable, depending on local manorial customs.

Shakespeare did not divide his lands equally. He used his will to leave his land and leases to his elder daughter Susanna Hall and to any potential sons she might have. He treated Susanna almost as a surrogate son, while still treating Judith as a daughter. Judith was left a substantial bequest of cash – generous for a daughter, but not equal.[ref]7. This included the possibility of a long-term annual income to be raised by Susanna. Depending on how Judith’s life turned out, she was due between £350 and £635 (the latter if she held an annuity until she died in 1662). Using the multiplier of 1:200 suggested by Nicholl in 2007, this was worth between £70,000 and £127,000 – so more than this today. See Charles Nicholl, ‘The Lodger: Shakespeare on Silver Street’ (2007), p xviii[/ref]

It’s possible that he was influenced by a local manorial custom from Rowington in the forest of Arden here, where the eldest daughter inherited if no son existed. Judith was given £50 for surrendering any possible right to a cottage in Stratford, held of the manor of Rowington. Was Shakespeare himself living within a local expectation and memory of strong women in the forest of Arden taking the part of men?

Anne Shakespeare is usually considered to have been badly done by: she was not mentioned in her husband’s will except for the famous bequest of the second-best bed, often interpreted as an insult. However, by custom, the first-best bed was always an heirloom, going with the main house to the heir. Anne was also left the bed outright, not just for the term of her life, which meant that she could dispose of it how she chose.

Many Shakespearean scholars also doubt that she was entitled to any property outside the will, extrapolating from an influential study of a Cambridgeshire village.[ref]8. Margaret Spufford, ‘Contrasting Communities: English Villagers in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries’ (1974), p 112.[/ref]

Somehow the particular custom of this village – that a widow lost her life interest in her late husband’s property if she remarried – has been extended by others westwards to the Midlands and to all forms of land-holding and to widows who did not remarry. Anne is therefore often said not have had any rights to her husband’s property after his death.

But was Anne left unprovided for? No: the extensive work of Erickson and Stretton makes it clear that a widow had a prior claim, before the heirs, to a life interest in her husband’s property. She would either have her customary dower rights (to a third of all lands) or a jointure (a more recent method, of income from specified lands), plus enjoyment of her household and personal goods. Anne’s lifetime rights took priority over the enjoyment of the full property by the heir: Susanna only received her full inheritance after her mother’s death in 1623.

Anne was not named as executor, but this does not mean she was hated or incapable. Susanna and her husband John were the executors, with the duty of paying out Judith’s marriage settlement, and acting as potential trustees for Judith: they were better placed to do this than Anne, by age and by role. Susanna was left with a lot of work to do (just as an eldest son would have been), raising capital for Judith and paying her interest.

If Anne’s rights had been withheld by Susanna, Anne could have gone to the court of Chancery like many other widows of her time – and we would have had much more evidence about the Shakespeare family.

Is there any more to tease out of the will?

Yes, lots more. David Foster and I will be presenting it at the World Shakespeare Congress study day at The National Archives on 8 August, and publishing it in the journal ‘Archives’ in late 2016.

Related blogs

Shakespeare’s daughters and female inheritance

Curation, collaboration and location: tracing Shakespeare through London

That’s really interesting, but please note: Ben Jonson, not Ben Johnson.

Thanks for flagging this up, Monica. I’ve updated the blog.

Best,

Nell

Fascinating stuff. There’s another Shakespeare will (1653) that leaves a ‘second best feather bed’ in TNA Prob 11/247.

I am surprised that staff are not allowed to handle it, even a limited number of staff, given that I understand the will was transferred to the Public Record Office in 1964 from the Principal Probate Office in London, I assume that someone must have touched it at the time.

It is quite fragile, and we limit the number of people who can access it, very tightly. I was able to look at it under the eagle eye of Nicola Fleming, both before and after it was conserved – but I could not touch it. Her blog about the conservation of the will is very interesting.

Your information and deductions are fascinating. However, as one who questions the authorship of Shakespeare’s works, I was very aware that you did not address what was not in the will. I’m not asking you to take sides on the authorship issue, but don’t you find it unusual that there are specific instructions about common household articles but no mention of books (very precious at that time), quartos of his works, or anything pertaining to his writing career. He was, of course, a good businessman. He will reflects that in many ways. But nothing pertains to his life as a playwright. (Note: my novel and my play, both entitled “The Shakespeare Conspiracy” make me very conscious of these omissions.)

I think that we need to read this will looking for this testator’s intentions, rather than compare it to the wills of people who were writing their wills with a different agenda. Shakespeare’s main motivation here is to ensure his daughters’ security, not to dispose of his personal goods. So no, I don’t think it is surprising that he does not list these in detail in this will.

It’s a real shame the inventory taken after his death does not survive – thanks to inventories of theis period being lost in the Great Fire in 1666.

I’m not sure what you mean by specific instructions in the will about common household articles: do you mean the broad silver gilt bowl left to Judith? You can see examples of this kind of large silver bowl at the Victoria and Albert Museum – they are very impressive displays of wealth and taste, but not common household articles!

Marston left no books in his will … neither did James Shirley who wrote some 38 plays and entertainments.

Amanda, no I was not referring to the silver bowl (which is mentioned twice). It would have been very valuable. But he left “all my wearing apparel” to his sister Joan and “all of my goods … and all the rest of my household stuff” to his daughter Judith.

Shirley and Marston were not the only authors whose wills omitted books and manuscripts. http://tiny.cc/no-books-in-authors-wills

Oh, I see. Yes, he does leave his sister Joan “all my wearing Apparell”, but he doesn’t into any detail about it.

He leaves “All the rest of my goodes Chattels Leases plate jewels and Household stuffe” to Susanna and her husband John Hall. I think this is a general ‘coverall’ bequest, so it could easily include books and papers – it covers for example the lease of the tithes of Stratford, which was a big investment.

Shakespeare was trying from at least 1613 to set up Susanna as the matriarch of a new ‘Hall’ line to preserve the family’s status; as the heir, she would have got all the family papers without them being specifically mentioned.

Because we now think that he amended his very formal will in March 1616 with personal bequests (mourning rings, the bed), he could then have decided to add instructions about books and papers. But as he didn’t, I think we have to assume they – whatever they were – went silently to Susanna and John.

Fascinating. I find these ideas about Shakespeare going to such lengths to protect his ‘manor’ through his daughter and ensure that she was provided for especially interesting in light of the interesting history we know about his mother. Thanks for sharing Amanda!

Fascinating – amazing work Amanda. (Very jealous!)

[…] Shakespeare’s will: a new interpretation […]

This is fascinating, and must have been very exciting to uncover. Do we know anything about Anne’s property and rights from her will or from other evidence of their disposal after her death?

Yes, it was exciting. Anne did not leave a will herself: most of her income or property was a life-interest in William’s property – although she did have a pretty good bed to dispose of! I wonder if she left it to Judith?

Fantastic insight Amanda. This should correct all the misinterpretations. As a

faithful reader and admirer of the Great Bard for the past 66 years -I THANK YOU.

Cecilia

Thank you Cecilia!

Very valuable and interesting contribution .- Unfortunately however, because a problem of authorship does not seem to exist for you , it might be that you do not ask the right questions!

For instance You are aware of “The Stratford story about Shakespeare’s death , that he died of a fever contracted after drinking with his fellow playwrights Michael Drayton and Ben Jonson.

As you well know Drayton is mentioned in the diary of Shaksperes son in law John Hall, as a famous poet but never Wm Shaksper his father in law? Why ? Do you have any idea what type of business Drayton had to do with Jonson in Stratford ? Why did Drayton in 1594 write a great poem about Gaveston [alias Marlowe’s self-identification in Edward II]? Etc.etc

In case of your interest you find some thoughts about Drayton in my Blog 274 , Blog 323, Blog 324 !

blog 323

http://www.der-wahre-shakespeare.com/blog-english/323ominous-1594the-context-of-shakespeareslucrece-draytons-gaveston-and-marlowes-edward-ii

blog 324

http://www.der-wahre-shakespeare.com/blog-english/324-drayton-similar-to-shake-speare-must-belong-to-the-code-names-of-concealed-marlowe-as-absurd-as-it-may-sound

Blog 274

http://www.der-wahre-shakespeare.com/blog-english/274-shakespeares-or-draytons-stratford-why-drayton-has-made-stratford-famous

Dear Bastian,

Michael Drayton had a very close friend who lived at Clifford Chambers, just across the Avon, whom he visited most Summers. John Hall treated him for constipation.

Drayton was nicknamed Roland and he came from the old Forest of Arden. I note that AYLI is set in the Forest of Arden and the male lead is Orlando whose father was Roland Du Bois.

Drayton was also a co-author of the Shakespeare play Sir John Oldcastle, a companion to HV, until it was discovered in Henslow’s Diaries that Shakespeare did not write it.

I understand the authorship question but the truth is not palatable.

Ben

[…] Amanda Bevan’s blog on her research into the will ‘Shakespeare’s will: a new interpretation’, which includes some of the multispectral images produced as part of the analysis is, available at: http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/shakespeares-will-new-interpretation/ […]

Dear Amanda,

I have just now caught up with your April article which prompts me to write.

Some years ago I also made a facsimile of the will and I concluded that page three folds differently to pages 1 & 2, and does not nestle with them as one would expect if they travelled through time together.

I wrote to the Archives a few years ago to relate some extraordinary findings I chanced upon. I was told to get the findings published in a journal.

With great confidence I can say that the first two pages of the Probate copy of the will are rewritten, in other words they are forgeries. I have looked at five wills written by the “same” scribe and in all cases the angle of the arm of the letter d is on average 36 degrees above the horizontal, as it is on the third page giving probate. In the Shakespeare will it is 38 degrees except for the third page where it reverts to 36 degrees. I have had the data checked by an admitted cynical statisticians at one of the local Universities and he confirms the Shakespeare probate copy is in a different hand. The wills I compared were William Polewheele, Samuel Daniell, and the two wills before and after Shakespeare’s. When one examines the initial signature “I” as In the name of god, amen, one can again see that the Shakespeare will is different, albeit a good imitation.

These are indisputable facts. I have done much more research and have theories which would really open up the authorship question. It will not stop me being in Stratford next week to see Cymbeline. I think someone should confirm my findings.

Regards

Ben Alexander

The original Will was taken up to the London Probate Office where two copies were made. One copy was kept as a probate record and the other copy was returned, with the original, to Stratford. That is what is stated in J.Thomas Looney’s 1922 publication (94 years ago) and JTL found nothing sinister in that quite usual process. So what’s new in all this -that copy and original were fiddled about?

No books? But by golly The Man could write couldn’t he – we know that because he left in autograph (?) a total of 12 words (“William Shakspear” x 6 times) in a shaky spidery script.

William Shakyhand more than likely.

[…] Shakespeare’s will: a new interpretation […]

Dear Ben

I am a little confused as to which version of the will we are discussing. The probate copy would be the one issued by the court as the authority for the executors to proceed.

If we are talking about the original will, I have to disagree with you. As part of our research on the will, we removed the very thick supporting paper glued to each page. It was amazing how the paper sprang back to life. The new images included in this blog, taken without the backing paper, show these folding lines very clearly – much more so than the colour images made available some years ago that I used for my textual research – and that perhaps you used too?

The “Second best bed” is probably the best bed, just slightly worn.

As in second-hand stuff! Meaning slightly worn.

F.G. Emmison came to this conclusion in a book called “Elizabethan Life” published by Essex County Council.

He came to this as a result at looking at lots of wills of the period. He even found references to the “worst bed”.

On the fever thing. You can also get a fever from liver failure. The result of drinking too much. And that is precisely what the record in 1660 by the vicar says he did.

Is there any more to tease out of the will?

I hope you will accept my spelling the man of Stratford’s name as “Shakspere”. I find it easier to think of “Shakspere” as being both potentially separate yet still involved in the works of “Shakespeare”.

William Shakspere made bequests to three small groups:

1. Family and only 2 close family friends.

2. His three “fellows”.

3. The remainders: the two overseers: Thomas Russell, Esq., (no residence given) and

Francis Collins of “the borough of Warr’ (Warwick), in the county of Warr’;

Mr.Thomas Combe to whom Shakspere leaves his sword and ;

William Reynolds, gent., who is among those who was to receive 26 shillings and 8 pence for the purchase of a ring.

On the face of it, all four have associations with Stratford upon Avon. Search deeper:

Thomas Russell, Esq.: A.J.Pointon in “The Man Who Was Never Shakespeare”, pp. 97-98 disagrees with Leslie Hotson’s identification of Thomas Russell, Esquire (who gave his residence as “of Rushock and Chaddesley” in his own will of 1633) being one of the overseers of Shakespeare’s will. At the time of the making of Shakspere’s will, Russell, a younger son of Sir Thomas Russell of Strensham and Great Witley, was probably still living at the property at Alderminster, some 4 miles from Stratford, that he had inherited from his father.

But Pointon is right to ask WHY?

Francis Collins: Francis, with his wife and children, were all left money from the1612/3 will of John Combe, of Old Stratford, gent., “the moneylender”. Collins, as “Francis Collys, gent.” was also a witness to the 1609 will of Thomas Combe of Old Stratford, brother of the above John, and father of Thomas Combe who was bequeathed the sword.

Mr.Thomas Combe: (note the “Mr.”; he was a lawyer, a Middle Temple man) was grandson of John ὰ Combes of Stratford by his first wife, Joyce Blount, daughter of Sir Thomas Blount of Kinlet, Shropshire.

William Reynolds, gent.: in the same 1612/3 will, the above John Combe left money to Thomas Reynolds, of Old Stratford, gent., his wife, Margaret, and their children. In this will, he calls Margaret, his “cousin”. Margaret Reynolds was the daughter of William Gower of Great Witley. Her first husband was a John Russell of Great Witley, of whom there is no known connection with Thomas Russell, Esq., Shakspere’s overseer, but with the name “Russell” and the Great Witley association, we can expect some kinship. Margaret’s second husband was Thomas Reynolds, father of William Raynoldes (sic), gent., to whom Shakspere left money for a ring. Thomas Reynolds was one of the sons of Alderman Hugh Reynolds of Stratford and his wife, Joyce Blount, daughter of Walter Blount of Astley.

As briefly, and I hope, as clearly as possible:

Generation 1: Descending from Sir Richard Croft of Croft Castle, Herefordshire, son of Janet, daughter of Glyndŵr and Sir John Croft (descended from Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence and Roger Mortimer, Earl of March).

Generation 2: a. Anne Croft (d 1549 and was buried at St.Mary’s Kidderminster) married Sir Thomas Blount of Kinlet (d 1525).

b. One of the sisters of Anne Croft married someone with the surname Gower. There are various Gowers called “cousin” by various Blounts.

Generation 3. From Sir Thomas Blount of Kinlet and Anne Croft, we have (among others):

a. Walter Blount of Astley, father of Joyce Blount of Astley, who married Hugh Reynolds of Stratford upon Avon, by whom Thomas Reynolds who married Margaret Gower, another descendant of Sir Richard Croft.

b. Joyce Blount , aunt of the above Joyce of Astley, who married John ὰ Combes of Stratford upon Avon at Kidderminster church in 1540. They were the parents of Thomas Combe of Old Stratford and grandparents of Thomas Combe to whom William Shakspere bequeathed his sword.

At this point we have two groups of Croft descendants living in Stratford:

1. Margaret Gower of Great Witley, who married 1. *a* John Russell of Great Witley, who was NOT the half-brother of Thomas Russell, Esq., overseer of Shakspere’s will, but was also, in some way, connected with the gentry family of the Russells of Strensham and Great Witley. Margaret Gower m.2. Thomas Reynolds of Stratford, by whom William Reynolds, to whom Shakspere left money for a ring.

2. Thomas Combe, grandson of Joyce Blount who married John ὰ Combes, at Kidderminster in 1540, as his first wife.

Mr.Thomas Combe and William Reynolds, gent. were 2nd cousins, their families originating in the adjacent Worcestershire parishes of Great Witley and Astley, just the other side of the River Severn from Droitwich, with Thomas Russell, Esq. already in possession of the Rushock lease, just north of Droitwich. As early as 1603 Russell had obtained the lease of Rushock, 2 miles from the strongly Catholic household at Harvington Hall, Worcestershire. Note that Shakspere, in 1616, is clear about the residence of the other overseer: Francis Collins, gent.: of “the borough of Warwick in the county of Warwick”, but he avoids giving Russell’s residence. By 1616 it is only a matter of time before Russell (d 1634) reveals himself as a closet-Catholic.

The Reynolds family and the Combe brothers by John ὰ Combe’s to Joyce Blount, were also Catholic, although as Mr.Thomas Combe was a lawyer, we can assume that he must have sworn allegiance to the Act of Uniformity. Margaret Reynolds , however, was charged with not receiving communion at Easter in 1606 while her son, William Reynolds, appeared before the Star Chamber some years later for rioting against the Puritans in Stratford and threatening to flay the local vicar.

So we have 3 groups remembered by Shakspere in his will, all Catholic, and originating in the Great Witley/Astley area, from “old” gentry families, who had only recently settled in Stratford. There is surely a story here.

That “second best bed”: One writer makes the following comment regarding Prof. Lawrence Stone’s research on the widow’s “one third” entitlement of their husbands’ estates. “Stone showed that the “one-third” provision only applied in London, Wales and York”. Stone was mistaken.

From one of my family’s documented history: the sale of 38 Mill Street, Cotten End, Warwick, in 1734, transcription held (if I remember correctly) at Worcester County Record Office, begins by identifying the parties:

“This indenture made … between Samuel Gazey of the Borough of Warwick in the County of Warwick (the exact wording used to identify the place of residence of Francis Collins) … and Susannah his wife on the one part and John Clemens of the Borough of Warwick aforesaid …”

The lawyer, responsible for the wording of this will covers every possible potential problem that might occur over this sale, including:

” that the said premises now are and from heretoforth shall for ever hereafter remain continue and be unto the said John Clemens his heires and assignes free and clear and freely and clearly acquitted exonerated and discharged of and from all and all manner of former and other bargaines gifts grants feefments sales leases mortgages deeds wills estates Intailes jointures dowers and more especially from the thirds or dower of Susannah wife of the said Samuel Gazey.”

A century after William Shakspere made his will, John Clemens’ shrewd lawyer protected his client from any claim that Samuel Gazey’s widow might make against the property being sold to him.

Anne Hathaway/Shakspere, like any woman, could still claim her widow’s thirds against the estate of her husband.

For a man not to make provision for his widow would be a scandal and a disgrace to his family.

We know that William Shakspere was ill; he was dying. It would be reasonable to expect that the will would have been tidied, made less bitter than it appears to us – but …

The “second best bed” – again

From: “Studies in Worcestershire History”, Humphreys, John, 1938, Cambridge University Press, pp.119-120:

“James I … revived the Penal Code, with even additional severity. A fresh enactment passed in the third year of his reign declared that:

‘All persons married otherwise than in some open church or chapel, and otherwise than according to the orders of the Church of England, by a minister lawfully authorised, shall be disabled to have any freehold, DOWER, THIRDS, etc., …’.”

i.e. in 1606 it was decreed that anyone not marrying in the Church of England would lose rights of dower and thirds; however, as Anne Hathaway/Shakspere was married before 1606 she WAS entitled to one third of her husband’s estate.

However, A.J.Pointon in “The Man Who Was Never Shakespeare”, p.94, tells his readers:

“Some have tried to claim that wife Anne had a right in law to one-third of her husband’s estate. Yet Lawrence Stone showed that the “one-third” provision only applied in London, Wales and York, and anyway, unless Shakspere’s will was invalid, Anne could have had no rights to any of the estate he identified in it – apart from “the bed”. This is consistent with the finding of Schoenbaum that other Stratford wills made substantial separate provision for wives, including that of the Francis Collins who drew up Shakspere’s.”

Francis Collins, one of the two overseers of the will of William Shakspere, made his will on 26th September, 1617, National Archives, PROB 11/130/512. He left to his wife: the ANNUITY OF FIVE POUNDS BY THE YEAR the which doth issue forth of my brother, Thomas Collins, his land at Inkford, for long as she doth keep my foresaid children, and keep herself unmarried …”

In addition to minor bequests Francis Collins left £20 each to his children: Francis, Alice, John, Thomas, Mary, Anne and Barbery together with £20 that Mr.Thomas Combe did promise to give to any (each) of my children, to be equally divided i.e. £160 in total.

He then left HALF OF THE RESIDUE OF HIS GOODS TO SUZAN, HIS WIFE and Francis, his son, whom he made executors. If Suzan were to live for a further 20 years, receiving an annuity of £5 a year, then Suzan did, indeed, receive a “substantial” amount.

In addition, although Collins does not specifically leave his family home to Suzan, other than “I give and devise to Francis, my son, all that house, barns, orchard and backside with all buildings thereto belonging AFTER THE DECEASE OF MY WIFE of her marriage … ” thereafter to the first son of his body lawfully to be begotten”, etc.

I agree with what Pointon says are Schoenbaum’s findings. I am deeply disturbed by what Pointon says of Stone’s sampling and his conclusions and the apparent perpetuation of those conclusions.

I live in Cyprus, where by Cyprus Law, a widow, whether Cypriot or any other nationality after living in Cyprus for so many years MUST still be left one third of her husband’s estate. This is also true of some other European countries. This is a very ancient right.

It is a frequent practice that a testator might leave a token bequest to a beneficiary who might have received benefit before the testator’s death – or who had been a disappointment to the testator – in order to avoid omitting one who might claim that the omission was an oversight. One might claim that the “second best bed” was such a token bequest, but no, Anne was entitled to her widow’s thirds.

We shall never know why Anne appears to have been left only the bed, but William was ill, he was dying; perhaps his executors and overseers agreed on his wishes as they understood them to be.

Gillian Palmer

On the 7th Feb 2018 I wrote that the first husband of Margaret nee Gower/Reynolds, wife of Thomas Reynolds of Stratford upon Avon was *a* John Russell.

This is probably incorrect. The will of Margaret’s father names, as his executor a John Russell, whom he calls his son-in-law, and secondly, Thomas Russell, also called son-in-law. William Gower had NO recorded son-in-law, nor step-son called John Russell by any of his four daughters. Either a proposed marriage between John Russell and Margaret Gower did not take place or was later annulled. And yet, her father named both men as his executor. One of the pedigrees for the Gower family has a fifth daughter, called Margery, but I am uneasy about this.

Extracts from the Will of William Gower, dated 7th February, 1592,

National Archives, PROB 11/85/313 p.229

In the name of god Amen, the seventh daye of ffebruary, Anno Domino thousand fyve hundred nynetie two

I give and bequeath to my daughter Margaret Reynolds twentie poundes in money xxx of silver and guilte, one stocke of fower oxen, twentie kyne and a Bull which is at Hawkley in the parish of Pensax and in the occupation of one George …my newe featherbed, one Bolster, one pillow and pillowbeere, one paire of blanketts, one coveringe, two payers of flaxen sheetes, two paire of hempen sheets and two paire of hurden sheets, one dozen of napkyns, and two table clothes, three of the third newest platters, three of the third newest pottingers and three of the third newest xxx my forth best pott my third best candlesticks and a coffer.

The residue of all my goodes not bequeathed (my Legacys payd, my funeralls discharged) I give and bequeath to John Russell my sonne in lawe, gent. whom I make and ordayne of this my present testament and last will my true sole and lawfull executor to see yt trylie performed uppon condition that he the sayed John Russell shall well and trulie discharge and paie all suche legaceys giftes and bequests by me given and bequeathed with the space of one quarter of a yeare next after my decease.

Contrarywise I ordayne and make Thomas Reynolds my sonne in lawe, gentleman, my true sole and lawfull executor to see this my present testament and last will performed as above written.

Brobatum testamentum London, Decimus septimo die mensis Maij Anno Domino … Johannis Russell.

Unexpected.

Gillian Gazey Palmer

Thank you for letting me hitch a lift on your blog. My thinking all started with your analysis of Shakespeare’s will, which mentions three people with Great Witley/Astley connections: Thomas Russell, William Reynolds and Thomas Combes.

The connections between Shakespeare and people who knew the above continues…

Thomas Reynolds, father of William, was the son of Hugh Reynolds and Joyce, daughter of Walter Blount, d 1561, of Astley.

Joyce’s brother, Robert Blount died in 1573, leaving bequests to “Frances Reynolds, daughter of Sister Hall (Joyce nee Blount) and to Elizabeth and Mary Hall, daughters of Joyce’s second husband Richard Hall of Idlicote.

Robert Blount’s son, Thomas, was not yet 21 years old at the time of the making of his father’s will.

Thomas’s first wife died and about 1590 he married, as his second wife, Bridget Brome, one of the daughters of Sir Christopher Brome of Holton, Nr.Oxford. This Thomas Blount was first cousin of Thomas Reynolds, father of William.

Sir Christopher Brome was related to Edward Ferrers, d 1633, of Baddesley Clinton and to Robert Burdett of Packwood House – both properties now owned by the National Trust and within comfortable walking distance of each other.

From: Raphael Holinshed: New Light on a Shadowy Life: Giving evidence in a Chancery lawsuit in March 1559, Holinshed stated that he had become an employee of Robert Burdet of Bramcote, Warwickshire, almost three years before the latter’s death and had then passed into the service of Robert’s son, Thomas Burdett (d.1591) … He certainly served the Burdets in a legal capacity, for, as their steward (Holinshed) he presided in the court of their manor of Packwood.

Given the proximity of these two homes and Sir Christopher Brome’s continued involvement in Baddesley Clinton, which had passed to the Ferrers family with the marriage of Constance Brome, d 1551, to Sir Edward Ferrers, d 1536, I would expect Thomas Blount and his wife, Bridget, nee Brome, to have known Raphael Holinshed personally.

To recap: Thomas Russell would have known Margaret nee Gower/Reynolds.

Margaret nee Gower married Thomas Reynolds; they were the parents of William Reynolds.

William Reynolds was also third cousin of Thomas Combes to whom William Shakespeare bequeathed his sword, being descended from Joyce Blount, daughter of Edward Blount of Kidderminster, brother of Walter Blount of Astley.

They all knew each other. And William Shakespeare knew all of them. And, if so, did William Shakespeare also know Raphael Holinshed personally?

Thank you again for posting for me.

Gillian Palmer

Shakespeare and the Sheldons

In his will, written in January and March 1616, William Shakespeare mentioned three people who were not known as being either friends or family:

1. Thomas Russell, to whom Shakespeare left £5 and who named him as one of his two overseers.

2. William Reynolds, to whom Shakespeare left money with which to purchase a ring. William Reynolds was the grandson of Isabel née Sheldon/Gower, wife of William Gower of Redmarley, Great Witley, Worcestershire.

3. Mr.Thomas Coombes, to whom Shakespeare bequeathed his sword. Mr.Thomas Combes, 1589-1657, Middle Temple lawyer, was the younger son of Thomas Coombes, d 1614, son of John à Combes of Stratford upon Avon, who had died by 1550, by his first wife, Joyce Blount, daughter of Edward Blount of Kidderminster. After Joyce’s death, John à Combes married Jane née Wheeler, who had previously been married to Baldwin Sheldon of Broadway, Worcestershire. Jane married, as her third husband, Thomas Lewkenor of Alvechurch.

Thomas, to whom Shakespeare bequeathed his sword, was therefore son of the step-son of Baldwin Sheldon of Broadway.

Note that William Shakespeare calls Thomas ʺMr.ʺ Thomas Coombes, as befits a lawyer.

Thomas Russell, the overseer, was the younger half-brother of Sir John Russell of Strensham and Great Witley, who married Elizabeth, eldest daughter of William Sheldon of Beoley, elder brother of Baldwin Sheldon of Broadway. Elizabeth was Catholic and John was Protestant and the marriage was not a happy one. At one time Sir John disinherited his three children, the youngest of whom was also called John. I have suggested that this younger John Russell might have been the ʺson-in-lawʺ, named executor in the will of William Gower.

The Sheldon Families of Beoley and Broadway

Ralph Sheldon of Abberton and his wife, Philippa Heath, had ten children, including William, of Beoley, Baldwin of Broadway and Isabel who married William Gower of Redmarley, Great Witley.

The Sheldons of Beoley, Worcestershire

William Sheldon of Beoley (d 1570) was the elder son of Ralph Sheldon of Abberton. William was lawyer to Queen Catherine Parr in her later years.

William’s eldest son was Ralph Sheldon of Beoley, 1537-1613, who married first, Anne Throckmorton, by whom several children including their eldest daughter, Elizabeth, who married John Russell of Strensham and Great Witley, elder half-brother of Thomas Russell of Rushock, William Shakespeare’s choice as one of the overseers of his will.

Extracts from in investigation by Hilary L.Turner online at http://www.tapestriescalledsheldon.info, 2018:

Öne of the men left in charge of the Sheldon carpet works was Thomas Chaunce, who died in 1603, leaving ʺgifts to my right worshipful friend Master Ralph Sheldon and to his daughter, Lady Russellʺ. Did Elizabeth Russell return to her father’s household after the death of her husband? Did her sons go with her?

Ralph Sheldon married, secondly, Jane West, who was the daughter of William West, (d.1596) 1st Baron de la Warr of the second creation. Jane was therefore the sister of Thomas West, 2nd Baron de la Warr, d 1602 and aunt of Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr, d June 1618, and his brother, Sir Francis West of the Virginia Company.

Jane née West was therefore step-mother of Elizabeth, Lady Sheldon.

From Geni: ʺ John Russell, the Emigrantʺ: (online)

ʺThe following is a collection of quotes and paraphrases from “The Russell Family In Early Virginia”, Chapter I “The Russell Family in England” by Louis des Cognets, Jr.

“John Russell was a student at Gloucester Hall (now Worcester College, Oxford), 17 Jan 1600/1, aged 13 (which would make him too young to be Sir John’s younger son, unless the above is the date of his graduation or further degree), of Worcester county, equitis fil (knight’s son). As there was only one Russell family in Worcester who were knights, and as his father Sir John Russell, had named his younger son John in his will of 1587, the identification is definite.”

“John Russell was. a member of the Second Supply; (Russell) sailed to America under the command of Thomas West, Lord Delawareʺ.

ʺThe bitter quarrel between his father (Sir John Russell) and his mother’s family, the Sheldons, might have been one factor that decided him to start life anew in a far country. … is among a list of gentlemen who landed at “James Cittie” (Jamestown, Virginia) in 1608.

ʺJohn Russell was mentioned in 1608 as one of the “gallants” of the Second Supply, and as a “proper gentleman”. Walter Russell, Doctor of Physicke, Francis West and George Yarrington (Yarranton) were also among those classed as gentlemen.

ʺThe following year of 1609 Captain John Smith and John Russell were left alone in a house with the Powhatan and a few squaws, when suddenly the crafty Indian disappeared, and a crowd of armed warriors surrounded the place. Without a moment’s hesitation Smith and Russell charged out with drawn swords. This was so unexpected that the savage tribesmen were taken by surprise, and fled in such haste that they tumbled over one another to get away from the sharp blades of the two Englishmen.ʺ

Jane née West/Sheldon was the sister of Thomas West, 2nd Lord de la Warr of the 2nd creation, d 1601, and aunt to Thomas West, 3rd Lord de la Warr, d 1618, Governor of the Virginia Company of London and of Francis West (28 October 1586 – February 1633/1634) who was a Deputy Governor of the Colony and Dominion of Virginia.

Therefore, there is strong reason for Geni’s suggestion that young John, the younger son of Elizabeth née Sheldon/Russell, was the above John Russell of Virginia.

William Shakespeare chose one of this family to act as overseer of his will. Compare this with the background notes that I remember from my school copy of the ʺTempest ʺ, that William Shakespeare obtained his information from listening to sailors down at London docks!

The Sheldons of Broadway, Worcestershire

Baldwin Sheldon of Broadway, d 1548, was the younger brother of William Sheldon of Beoley. He married Jane née Wheeler, as her first husband. Jane married, secondly, John à Combes of Stratford upon Avon, by which marriage she became step-mother to, among others, Thomas Combe, father of Thomas Combe, to whom William Shakespeare bequeathed his sword. John à Combe and Jane née Wheeler had a son, William, born after the death of his father and who died in 1610.

This William Combe, was the Middle Temple lawyer of Warwick, who died in 1610, and is often incorrectly confused with ʺUncle William Combeʺ who was involved in land transactions with William Shakespeare in 1602. Jane née Wheeler’s third marriage was to Thomas Lewkenor of Alvechurch, father of two children: Jane and Nicholas Lewkenor

Baldwin Sheldon of Broadway, d 1548, and Jane née Wheeler had several children, their eldest son being William Sheldon, buried 1626, who is believed to have been the witness to the 1602 indenture by which Uncle William Combe (presumably a brother of John à Combe, senior), sold land to William Shakespeare of Stratford. (SBTRO ER 27/1).

Temple Grafton

From: British History Online: Temple Grafton:

ʺThe manor of Temple Grafton passed to the Crown, and by an Act of 32 Henry VIII was included in the jointure of Queen Katherine Parr. In 1545, however, it was granted with other estates to William Sheldon and John Draper (alias Mercer) of Temple Grafton .ʺ

(I am assuming that the above William Sheldon was William Sheldon of Beoley, elder brother of Baldwin Sheldon of Broadway. William Sheldon had been lawyer to Queen Catherine Parr. Who received Temple Grafton in her jointure. Margaret and Brace Sheldon, below, were two of the children of Anthony Sheldon of Broadway and his wife, Jane née Lewkenor. Gillian Palmer.)

ʺTemple Grafton was allotted to John Draper. In 1548 Draper settled the manor on his son Robert, reserving a moiety to his wife Margery for her life; John died in 1556. Margery Draper died in 1558 and Robert in 1563, leaving a son and heir William, who received the manor on coming of age in 1583. William Draper married Margaret daughter of Anthony Sheldon of Broadway (2nd son of Baldwin Sheldon of Broadway: Gillian) and, having no issue, settled the manor on Brace Sheldon, his brother-in-law. ʺ

i.e. William Draper was lord of the manor of Temple Grafton in 1583, and most probably involved in the manor before reaching the age of 21. William was about 20 years old in 1582, the year that 18 year old William Shakespeare obtained a licence to marry Anne Whateley of Temple Grafton.

The entry from the Bishop of Worcester’s register, dated November 27th, 1582 records that a license was granted to William Shakespeare for his marriage to Anne Whateley of Temple Grafton. However, a bond dated the next day states that there was nothing to prevent the marriage taking place between William Shakespeare and Anne Hathaway of Stratford-upon-Avon, and that the bishop would be safeguarded from any future possible objections.

Temple Grafton is in the diocese of Worcester. The bishop of Worcester at the time of Shakespeare’s marriage bond was the moderate John Whitgift who was Bishop of Worcester from 1577 to 1583 before translating to become Archbishop of Canterbury.

I propose that 21 year old William Draper, later to marry Margaret, daughter of Anthony Sheldon of Broadway and shortly to become lord of the manor of Temple Grafton, would have known the 18 year old William Shakespeare.

The Cotswold Olympics: Fun and games at the edge of the Cotswolds, overlooking the Vale of Evesham, which were started around 1612 by by Robert Dover of Saintbury, d 1652.

From: ʺThe Merry Wives of Windsorʺ: ʺHow does your fallow greyhound, sir? I heard say he was outrun on Cotswold.ʺ

Saintbury is sheep country. My daughters’ Saintbury forebears include shepherds and a gloveress (did John Shakespeare, two centuries earlier, employ outworkers?)

The Cotswold Olympics were quite the social event of the time. King James could not make it but he sent a set of his own clothes for Robert Dover to wear while presiding over the festivities.

I constantly read the thought that perhaps William Shakespeare might have attended. After enjoying a lifetime enthralling his audience, I am sure that he did. His presence – the man whose acting drew tens of hundreds by bridge and wherry across the River Thames whenever the flag went up on the Globe – would not have missed the Cotswold Olympics.

And the Sheldons of Broadway – only a short ride away -would also, most certainly, have attended.

Summary: William Shakespeare knew the Sheldons

1. Shakespeare entrusted Thomas Russell, who – I suggest – called his half-brother’s younger son, John Russell, his ʺson-in-lawʺ, with the overseeing of his will..

2. He bequeathed money for a ring to William Reynolds, grandson of Isabel Sheldon, wife of William Gower of Great Witley.

3. He bequeathed his sword to Mr.Thomas Combe, son of Thomas Combe, who Shakespeare would have known and who was step-brother to the Sheldons of Broadway family.

4. 18 year old William Shakespeare applied for a licence to marry Anne Whateley of Temple Grafton, a manor belonging to William Draper, shortly to marry Margaret, daughter of Anthony Sheldon and his wife, Jane née Lewkenor, of Broadway.

5. He would – surely – not have missed out on all the fun of the Cotswold Olympics, 12 miles distance from Stratford upon Avon and only three miles by horse from The Sheldon’s home at Broadway.

The subject of the authorship of the plays and poems of William Shakespeare speaks as much of the contenders as it does of the Shakespeare himself.

One writer has stated:

ʺThe fact that Russell of Rushock cannot be linked to Shakespeare, means that other Hotson fantasies about how that man introduced Shakespere to a network of aristocrats and establishments, from the Earl of Essex to the Virginia Company, evaporate.ʺ

I leave this thought with your readers.

Best wishes,

Gillian Gazey Palmer

Sorry. Another go, with better grammar:

Shakespeare and the Sheldons

In his will, written in January and March 1616, William Shakespeare mentioned three people who were not known as being either friends or family:

1. Thomas Russell, to whom Shakespeare left £5 and who named him as one of his two overseers.

2. William Reynolds, to whom Shakespeare left money with which to purchase a ring. William Reynolds was the grandson of Isabel née Sheldon/Gower, wife of William Gower of Redmarley, Great Witley, Worcestershire.

3. Mr.Thomas Coombes, to whom Shakespeare bequeathed his sword. Mr.Thomas Combes, 1589-1657, Middle Temple lawyer, was the younger son of Thomas Coombes, d 1614, son of John à Combes of Stratford upon Avon, who had died by 1550, by his first wife, Joyce Blount, daughter of Edward Blount of Kidderminster. After Joyce’s death, John à Combes married Jane née Wheeler, who had previously been married to Baldwin Sheldon of Broadway, Worcestershire. Jane married, as her third husband, Thomas Lewkenor of Alvechurch.

Thomas, to whom Shakespeare bequeathed his sword, was therefore son of the step-son of Baldwin Sheldon of Broadway.

Note that William Shakespeare calls Thomas ʺMr.ʺ Thomas Coombes, as implies a lawyer.

Thomas Russell, the overseer, was the younger half-brother of Sir John Russell of Strensham and Great Witley, who married Elizabeth, eldest daughter of William Sheldon of Beoley, elder brother of Baldwin Sheldon of Broadway. Elizabeth was Catholic and John was Protestant and the marriage was not a happy one. At one time Sir John disinherited his three children, the youngest of whom was also called John. I have suggested that this younger John Russell might have been the ʺson-in-lawʺ, named executor in the will of William Gower.

The Sheldon Families of Beoley and Broadway

Ralph Sheldon of Abberton and his wife, Philippa Heath, had ten children, including William, of Beoley, Baldwin of Broadway and Isabel who married William Gower of Redmarley, Great Witley.

The Sheldons of Beoley, Worcestershire

William Sheldon of Beoley (d 1570) was the elder son of Ralph Sheldon of Abberton. William was lawyer to Queen Catherine Parr in her later years.

William’s eldest son was Ralph Sheldon of Beoley, 1537-1613, who married first, Anne Throckmorton, by whom several children including their eldest daughter, Elizabeth, who married John Russell of Strensham and Great Witley, elder half-brother of Thomas Russell of Rushock, William Shakespeare’s choice as one of the overseers of his will.

Extracts from in investigation by Hilary L.Turneronline at http://www.tapestriescalledsheldon.info, 2018

Thomas Chaunce, one of the men left in charge of the Sheldon carpet works was Thomas Chaunce, who died in 1603, leaving ʺgifts to my right worshipful friend Master Ralph Sheldon and to his daughter, Lady Russellʺ. Did Elizabeth Russell return to her father’s household after the death of her husband? Did her sons go with her?

Ralph Sheldon married, secondly, Jane West, who was the daughter of William West, (d.1596) 1st Baron de la Warr of the second creation. Jane was therefore the sister of Thomas West, 2nd Baron de la Warr, d 1602 and aunt of Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr, d June 1618, and his brother, Sir Francis West of the Virginia Company.

Jane née West was therefore step-mother of Elizabeth, Lady Sheldon.

From Geni: ʺ John Russell, the Emigrantʺ: (online)

ʺThe following is a collection of quotes and paraphrases from “The Russell Family In Early Virginia”, Chapter I “The Russell Family in England” by Louis des Cognets, Jr.

“John Russell was a student at Gloucester Hall (now Worcester College, Oxford), 17 Jan 1600/1, aged 13 (which would make him too young to be Sir John’s younger son, unless the above is the date of his graduation or further degree), of Worcester county, equitis fil (knight’s son). As there was only one Russell family in Worcester who were knights, and as his father Sir John Russell, had named his younger son John in his will of 1587, the identification is definite.”

“John Russell was. a member of the Second Supply; (Russell) sailed to America under the command of Thomas West, Lord Delawareʺ.

ʺThe bitter quarrel between his father (Sir John Russell) and his mother’s family, the Sheldons, might have been one factor that decided him to start life anew in a far country. … is among a list of gentlemen who landed at “James Cittie” (Jamestown, Virginia) in 1608.

ʺJohn Russell was mentioned in 1608 as one of the “gallants” of the Second Supply, and as a “proper gentleman”. Walter Russell, Doctor of Physicke, Francis West and George Yarrington (Yarranton) were also among those classed as gentlemen.

ʺThe following year of 1609 Captain John Smith and John Russell were left alone in a house with the Powhatan and a few squaws, when suddenly the crafty Indian disappeared, and a crowd of armed warriors surrounded the place. Without a moment’s hesitation Smith and Russell charged out with drawn swords. This was so unexpected that the savage tribesmen were taken by surprise, and fled in such haste that they tumbled over one another to get away from the sharp blades of the two Englishmen.ʺ

Jane née West/Sheldon was the sister of Thomas West, 2nd Lord de la Warr of the 2nd creation, d 1601, and aunt to Thomas West, 3rd Lord de la Warr, d 1618, Governor of the Virginia Company of London and of Francis West (28 October 1586 – February 1633/1634) who was a Deputy Governor of the Colony and Dominion of Virginia.

Therefore, there is strong reason for Geni’s suggestion that young John, the younger son of Elizabeth née Sheldon/Russell, was the above John Russell of Virginia.

William Shakespeare chose one of this family to act as overseer of his will. Compare this with the background notes that I remember from my school copy of the ʺTempest ʺ, that William Shakespeare obtained his information from listening to sailors down at London docks!

The Sheldons of Broadway, Worcestershire

Baldwin Sheldon of Broadway, d 1548, was the younger brother of William Sheldon of Beoley. He married Jane née Wheeler, as her first husband. Jane married, secondly, John à Combes of Stratford upon Avon, by which marriage she became step-mother to, among others, Thomas Combe, father of Thomas Combe, to whom William Shakespeare bequeathed his sword. John à Combe and Jane née Wheeler had a son, William, born after the death of his father and who died in 1610.

This William Combe, was the Middle Temple lawyer of Warwick, who died in 1610, and is often incorrectly confused with ʺUncle William Combeʺ who was involved in land transactions with William Shakespeare in 1602. Jane née Wheeler’s third marriage was to Thomas Lewkenor of Alvechurch, father of two children: Jane and Nicholas Lewkenor

Baldwin Sheldon of Broadway, d 1548, and Jane née Wheeler had several children, their eldest son being William Sheldon, buried 1626, who is believed to have been the witness to the 1602 indenture by which Uncle William Combe (presumably a brother of John à Combe, senior), sold land to William Shakespeare of Stratford. (SBTRO ER 27/1).

Temple Grafton

From: British History Online: Temple Grafton:

ʺThe manor of Temple Grafton passed to the Crown, and by an Act of 32 Henry VIII was included in the jointure of Queen Katherine Parr. In 1545, however, it was granted with other estates to William Sheldon and John Draper (alias Mercer) of Temple Grafton .ʺ

(I am assuming that the above William Sheldon was William Sheldon of Beoley, elder brother of Baldwin Sheldon of Broadway. William Sheldon had been lawyer to Queen Catherine Parr. Who received Temple Grafton in her jointure. Margaret and Brace Sheldon, below, were two of the children of Anthony Sheldon of Broadway and his wife, Jane née Lewkenor. Gillian Palmer.)

ʺTemple Grafton was allotted to John Draper. In 1548 Draper settled the manor on his son Robert, reserving a moiety to his wife Margery for her life; John died in 1556. Margery Draper died in 1558 and Robert in 1563, leaving a son and heir William, who received the manor on coming of age in 1583. William Draper married Margaret daughter of Anthony Sheldon of Broadway (2nd son of Baldwin Sheldon of Broadway: Gillian) and, having no issue, settled the manor on Brace Sheldon, his brother-in-law. ʺ

i.e. William Draper was lord of the manor of Temple Grafton in 1583, and most probably involved in the manor before reaching the age of 21. William was about 20 years old in 1582, the year that 18 year old William Shakespeare obtained a licence to marry Anne Whateley of Temple Grafton.

The entry from the Bishop of Worcester’s register, dated November 27th, 1582 records that a license was granted to William Shakespeare for his marriage to Anne Whateley of Temple Grafton. However, a bond dated the next day states that there was nothing to prevent the marriage taking place between William Shakespeare and Anne Hathaway of Stratford-upon-Avon, and that the bishop would be safeguarded from any future possible objections.

Temple Grafton is in the diocese of Worcester. The bishop of Worcester at the time of Shakespeare’s marriage bond was the moderate John Whitgift who was Bishop of Worcester from 1577 to 1583 before translating to become Archbishop of Canterbury.

I propose that 21 year old William Draper, later to marry Margaret, daughter of Anthony Sheldon of Broadway and shortly to become lord of the manor of Temple Grafton, would have known the 18 year old William Shakespeare.

The Cotswold Olympics: Fun and games at the edge of the Cotswolds, overlooking the Vale of Evesham, which were started around 1612 by by Robert Dover of Saintbury, d 1652.

From: ʺThe Merry Wives of Windsorʺ: ʺHow does your fallow greyhound, sir? I heard say he was outrun on Cotswold.ʺ

Saintbury is sheep country. My daughters’ Saintbury forebears include shepherds and a gloveress (did John Shakespeare, two centuries earlier, employ outworkers?)

The Cotswold Olympics were quite the social event of the time. King James could not make it but he sent a set of his own clothes for Robert Dover to wear while presiding over the festivities.

I constantly read the thought that perhaps William Shakespeare might have attended. After enjoying a lifetime enthralling his audience, I am sure that he did. His presence – the man whose acting drew tens of hundreds by bridge and wherry across the River Thames whenever the flag went up on the Globe – would not have missed the Cotswold Olympics.

And the Sheldons of Broadway – only a short ride away -would also, most certainly, have attended.

Summary: William Shakespeare knew the Sheldons

1. Shakespeare entrusted Thomas Russell, who – I suggest – called his half-brother’s younger son, John Russell, his ʺson-in-lawʺ, with the overseeing of his will..

2. He bequeathed money for a ring to William Reynolds, grandson of Isabel Sheldon, wife of William Gower of Great Witley.

3. He bequeathed his sword to Mr.Thomas Combe, son of Thomas Combe, who Shakespeare would have known and who was step-brother to the Sheldons of Broadway family.

4. 18 year old William Shakespeare applied for a licence to marry Anne Whateley of Temple Grafton, a manor belonging to William Draper, shortly to marry Margaret, daughter of Anthony Sheldon and his wife, Jane née Lewkenor, of Broadway.

5. He would – surely – not have missed out on all the fun of the Cotswold Olympics, 12 miles distance from Stratford upon Avon and only three miles by horse from The Sheldon’s home at Broadway.

The subject of the authorship of the plays and poems of William Shakespeare speaks as much of the contenders as it does of the Shakespeare himself.

One writer has stated:

ʺThe fact that Russell of Rushock cannot be linked to Shakespeare, means that other Hotson fantasies about how that man introduced Shakespere to a network of aristocrats and establishments, from the Earl of Essex to the Virginia Company, evaporate.ʺ

I leave this thought with your readers.

Best wishes,

Gillian Gazey Palmer

More thoughts on the Sheldons and William Shakespeare 18th March 2021:

William Shakespeare, Thomas Lewkenor and the Sheldon family Gillian Palmer 14th March 2021

Descendants of Ralph Sheldon (1476-1546) of Abberton & Beoley and his wife, Philippa Heath, sister of Nicholas Heath, Bishop of Worcester, and later, Archbishop of York, temp. Queen Mary Tudor.

Generation 1: Ralph Sheldon, d 1546 and Philippa née Heath.

Generation 2:

A. William Sheldon, d 1570, of Abberton and Sheldon, elder son of Ralph and Philippa Sheldon. Lawyer to Queen Catherine Parr, from whom he acquired Temple Grafton.

B. Baldwin Sheldon of Broadway, who married: 1. Jane Wheeler, previously married to John à Combes (I) of Stratford upon Avon. Jane née Wheeler/Combes/Sheldon/ Lewknor married 3. Thomas Lewknor of Alvechurch, who had been previously married (before 1553) to Johan (Jane) Challoner b 1521 (not Bennet Challoner as sometimes stated on internet sources).

C. Mary Sheldon who married 2. George Ferrers of the Baddesley Clinton, Warwickshire,

family, which is only 4 km from Packwood House, at the time when Raphael Hollinshed was steward to the Burdett family living at Packwood House.

D. Isobel Sheldon m William Gower of Redmarley Gt.Witley, Worcestershire. William Gower appointed John Russell (nephew of Thomas Russell, one of the overseers of the will of William Shakespeare) as executor of his will, but Gower also stated that otherwise the overseer should be Thomas Reynolds, his son-in-law.

Generation 3.

A. i. Ralph Sheldon of Beoley, d 1613, son of William Sheldon, d 1570, generation 2.A.

B.i. Thomas Combe, d 1608, of Stratford upon Avon, son of Jane Wheeler and her first husband, John à Combe (I) of Stratford upon Avon.

B.ii. John à Combe (II), the “moneylender”, another of the sons of John à Combes (I) ,who was mentioned by William Shakespeare in his will.

C. Anthony Sheldon, 2nd son of Baldwin Sheldon of Broadway, Worcestershire, Generation 2.B, who married Jane Lewkenor, daughter of his step-father, Thomas Lewkenor of Alvechurch, Generation 2.B and his first wife, Johan Challoner.

D. Margaret Gower, daughter of William Gower of Gt.Witley, Worcestershire, and his wife, Isobel Sheldon, one-time neighbour at Great Witley, Worcestershire, of Thomas Russell, one of the two overseers named in his will by William Shakespeare. Margaret née Gower married Thomas Reynolds, son of Alderman Hugh Reynolds of Stratford upon Avon and his wife, Joyce Blount, daughter of Walter Blount of Astley, Worcester, adjacent parish to Gt.Witley. Joyce née Blount/Reynolds, daughter of Thomas Blount of Astley, married 2. Richard Hall of Idlicote.

Generation 4.:

A. Edward Sheldon, only son of Ralph Sheldon of Beoley, d 1613. Edward, however, had nine sisters, including Elizabeth, who married John Russell of Strensham, the elder half- brother of Thomas Russell, named by William Shakespeare of Stratford upon Avon, as one of the two overseers of his will.

B. Thomas Combe (1589-1657), lawyer, elder son of Thomas Combe, d 1608/9, Generation 3.B. to whom William Shakespeare bequeathed his sword.

C.i. William Sheldon, baptised Alvechurch, who died in 1626, who married Cecily Brace, d 1613.

C.ii Margaret Sheldon, baptised Alvechurch, who married in 1580, William Draper, who acquired Temple Grafton (See Gen.2.A.) on reaching the age of 21 years in 1583, the year after William Shakespeare received permission to marry Anne Whatley of Temple Grafton. There was no issue to the marriage of William and Margaret Draper, so William Draper left Temple Grafton to his brother-in-law, Baldwin Sheldon.

C.iii Baldwin Sheldon,bap 1577, Broadway, who married Eleanor Bishop of Temple Grafton in 1599 and who acquired Temple Grafton from his brother-in-law, William Draper.

D.i. William Reynolds, son of Thomas Reynolds of Stratford upon Avon , and his wife, Margaret, née Gower/Reynolds, to whom William Shakespeare bequeathed 26 shillings and 6 pence for the purchase of a ring.

Generation 5:

A.. William Sheldon, d 1659, son of Edward Sheldon, son of Edward Sheldon and nephew of Elizabeth nee Sheldon/Russell, wife of John Russell, elder half-brother of Thomas Russell, one of the overseers of the will of William Shakespeare. In 1628 this William Sheldon purchased the Vincent Folio of the First Folios.

I find the number of associations between William Shakespeare and the Sheldon family very curious.

Best wishes, Gillian Gazey Palmer

If thy soul check thee that I come so near,

Swear to thy blind soul that I was thy Will,

And will, thy soul knows, is admitted there;

Thus far for love, my love-suit, sweet, fulfil.

Will, will fulfil the treasure of thy love,

Ay, fill it full with wills, and my will one.

In things of great receipt with ease we prove

Among a number one is reckoned none:

Then in the number let me pass untold,

Though in thy store’s account I one must be;

For nothing hold me, so it please thee hold

That nothing me, a something sweet to thee:

Make but my name thy love, and love that still,

And then thou lovest me for my name is ‘Will’.

Sonnets 136 and 135 should be read in the context that will was a euphemism for genitalia, both male and female. They are more than salacious.

Ben