Our audio drama project Being and Not Being was born from exploratory conversations about Second World War records in Swahili and Hindustani here at The National Archives.

The presence of these records in our collection speaks to the Second World War as a global conflict, with diverse legacies for communities around the world. We wondered what audio drama might be able to do to bring exposure to these records, and to open up conversations with different diasporic groups in the UK about their family memories and histories of the Second World War. Next year, 2025, marks the 80th anniversary of the end of the conflict.

As we describe in the previous blog in this series, The National Archives has been commissioning audio drama for nearly a decade as a way of engaging audiences with the human stories behind our records. Usually, the records that form the focus of these dramas have been letters or petitions that speak directly to the experiences of a specific individual.

The records we have in Hindustani and Swahili are quite different – largely training manuals, language teaching materials, and propaganda. They don’t present easy entry points for writers to start from. However, a team from Applied Stories – Fin Kennedy, and writers Sharmila Chauhan and Ery Nzaramba – were ready to take on the challenge. Drawing from a page about grammar in a Swahili language manual, the project took on the title ‘Being and Not Being’.

The largest volunteer army in history

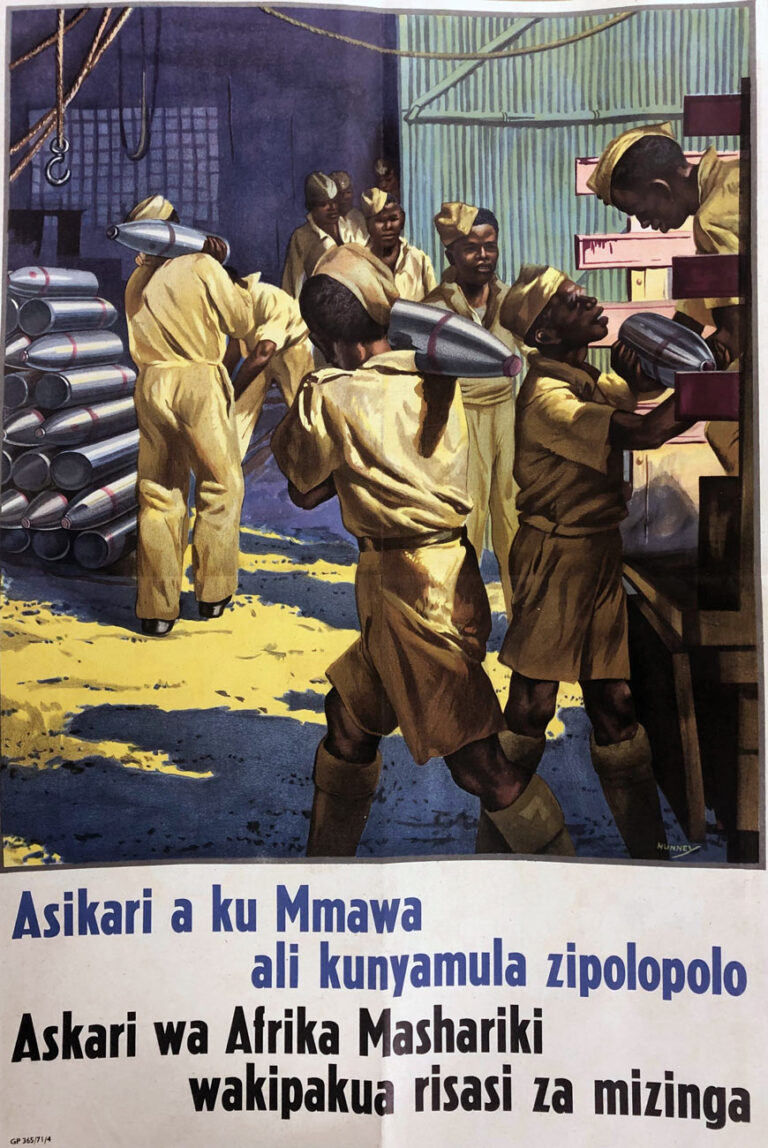

The records this project draws on are the legacies of participation in the Second World War by combatants and non-combatants who came from territories under colonial administration. There were millions such servicemen and women around the world, and in this case we focused on those recruited in East Africa and South Asia.

In both of these regions, recruitment was – in principle – voluntary, although scholars have described how this wasn’t always the case. In both, recruitment expanded very rapidly. The Indian Army went from around 200,000 men at the outbreak of the Second World War to a force that counted 3.35 million at its peak (by some estimates), making it the largest volunteer force in history. The King’s African Rifles (the regiment for East Africa) was relatively smaller but also increased rapidly in size during the conflict.

In both contexts soldiers faced criticism from their contemporaries as collaborators with the British colonial authorities. Once enlisted, colonial troops were discriminated against in terms of pay and conditions of service, as well as experiencing outright racism. As combatants they faced death, injury and capture, fighting across East and North Africa, India, South-East Asia and Europe.

In these challenging situations soldiers had to learn new skills, including languages, very quickly. The British army elected to use Swahili and Hindustani as common languages within the King’s African Rifles and Indian Army. These were not the first languages for most of the soldiers, many of whom would have been raised in one of a large number of languages in each region. They were often learning two languages (English and the common languages) as well as technical skills and military drills, all at the same time. As one member of the King’s African Rifles testifies in our records:

‘”Right turn” and “left turn” is all Greek to him. He has never heard of them, so the African soldier has not only to learn movements but the language as well at the same time’.

Robert H Kakembo, An African Speaks, 1944. Catalogue reference: CO 1073/308

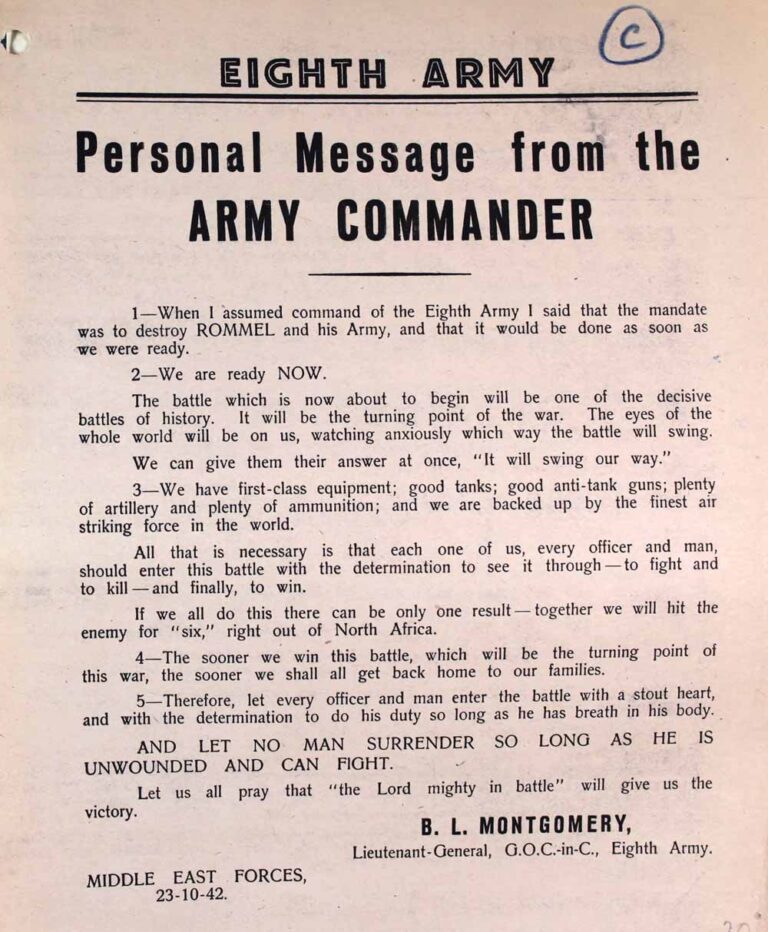

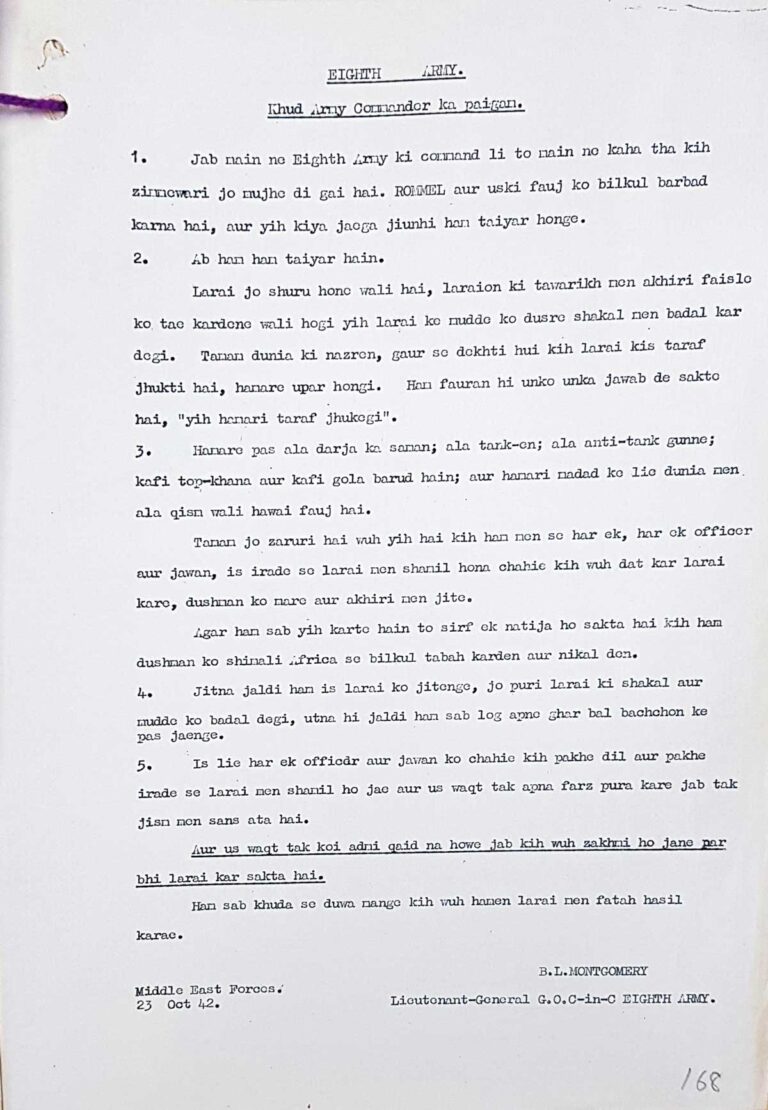

Complex orders and even motivational speeches were passed through chains of translation and written in an emotive register, for maximum impact. Here is one from Bernard Law Montgomery, who was General Officer Commanding, Eighth Army, to the troops he was leading in North Africa in October 1942. At that point, the Eighth Army was made up of seven British divisions, two Indian Divisions, an Australian Division and one from New Zealand.

This speech was translated into romanised Hindustani (Hindustani written using a roman alphabet) to be delivered to the Eighth Army’s Indian troops:

Understanding troops’ experiences

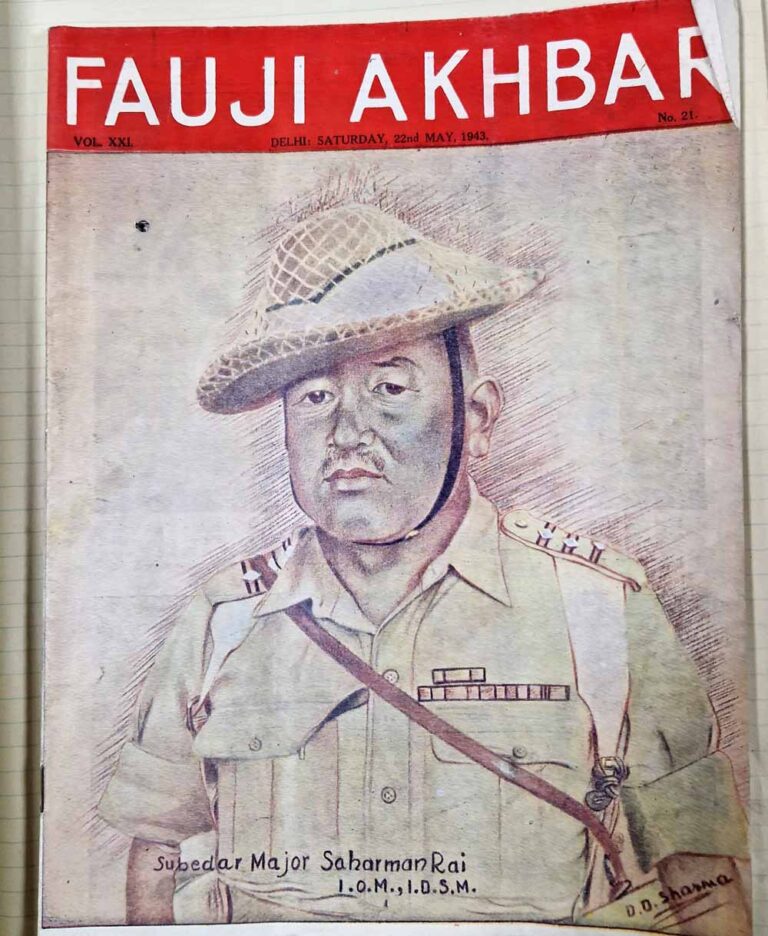

The records we have been looking at are largely from the collections of the Colonial Office and the War Office. They speak to topics such as recruitment, morale and maintaining loyalty, for example including magazines with photos and illustrations that were popular among Indian troops. They also speak to troops’ experiences. Kakembo’s autobiographical account is an unusual example of a first-person view of life in these armies.

More often our collections offer fragments of insights, such as reports of morale among the troops that were produced by censors from reading soldiers’ letters home. Some historians have done oral history work with veterans and their communities in East Africa and South Asia, but even in other contexts like these, autobiographical accounts of the conflict are relatively rare.

A collaborative approach to writing

The writers of ‘Being and Not Being’ responded to the challenge of exploring these records with incredible skill and imagination. Over a period of more than six months, they worked with our collections, with Fin Kennedy and with the sound designer Farokh Soltani to produce richly layered dramas. They take the listener to the recruiting office, the school room, to the cinema, to battle zones, and beyond.

Since March, through a series of workshops, we have invited reflection on the work-in-progress with other creative practitioners, academics and heritage professionals from the UK, East Africa, South Asia and beyond. At the end of June we were able to showcase the final dramas with staff and students from SOAS (the School of Oriental and African Studies, London), and we look forward to taking it to further audiences over the coming months.

In our final blog in this series, we’ll be inviting you to step into the creative process of working with these records, from the point of view of the writers, Ery Nzaramba and Sharmila Chauhan. What does it mean for writers to work with archival collections? How do you go about building exciting drama from reports and training manuals? Look out for the next instalment to learn more.