Normally, the first thing that comes to my mind when thinking of mining in Britain is Poldark, the BBC’s TV series.

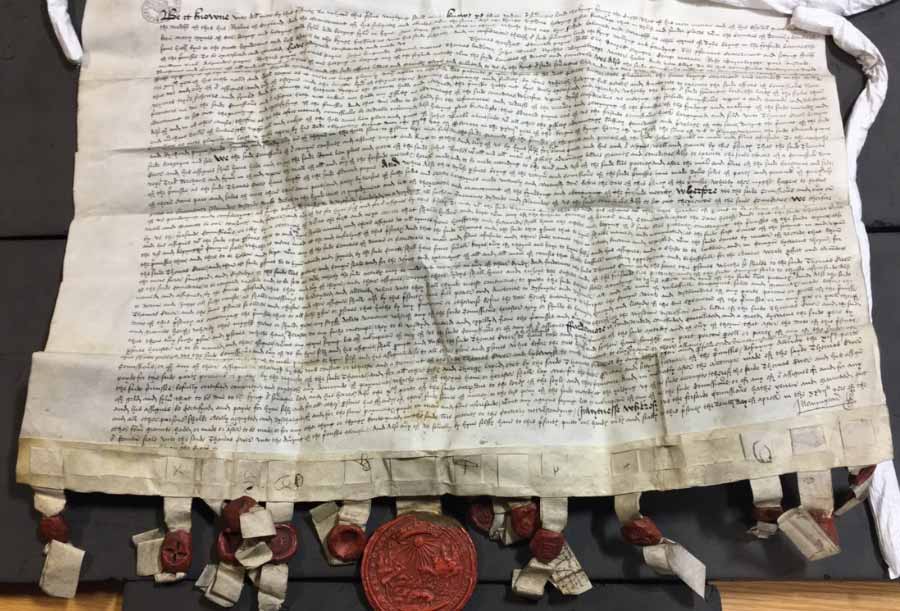

When I started my work placement at The National Archives I knew that there must be numerous written records on the history of mining, from the Industrial Revolution onwards. However, I had no idea that my interest in seals would involve finding what must be one of the earliest pictorial representations of mining in Britain, even predating the 18th century. This beautifully preserved seal, surrounded by 13 smaller seals, is attached to a document written in English and dated 1536 (E41/129; E41/130).

The commission, 1536 (catalogue reference: E41/129; E41/130)

The document itself is the appointment of Thomas Ewer as a Commissioner to search for and mine gold, silver, and other metals (except tin) in Devon and Cornwall. A citizen and merchant tailor of London, he replaced a surveyor of the tin mines named John Barbour. It states that all the metals fraudulently sold prior to this commission were to be recovered and returned to their rightful owners, with the assumption that Ewer and his associates would prevent this from happening in the future.

The large red seal, measuring 2.5 cm in diameter, is the Common Seal of the commissioners of tin mining for Cornwall and Devon. The smaller seals are the personal seals of the individual commissioners.[ref]1. A commissioner was a representative of the supreme authority in an area.[/ref]

The Common Seal, 1536 (catalogue reference: E41/129; E41/130)

The seals themselves tell a story, which for me adds to the real interest of this document. Before this project, I would have overlooked the value of the non-textual elements of the record, as at first sight they did not add to my understanding of it. The purpose of a seal is to validate the document to which it is attached. Obviously the text is vital in understanding the document, but I will mainly be concentrating on the seals themselves.

The Common Seal depicts a mining scene in Tudor Devon and Cornwall and some of the processes which were used. Three miners are shown: the one on the right has a spade with a triangular blade, the one on the left is using a mattock, and the one in the middle is sieving in a river perhaps for gold.

The Arched or Imperial crown at the top emphasises that the commission had originally been granted by the King. The letters ‘D’ and ‘C’ appear on either side of the sun and possibly represent Devon and Cornwall and the stannaries’ court.[ref]2. The Stannary Courts were legal institutions in England, created to protect the interests of tin miners and tin mining. Edward I established three Stannary towns in 1305: Tavistock, Ashburton and Chagford. Later in 1307 Plympton became the fourth and final Stannary town.[/ref] Beneath the two letters there appears to be a ship coming into port and on the other side a castle with turrets, perhaps representing the trading opportunities and status of the mining community in Devon and Cornwall. The sun, which is often used as an analogy for deity in the early modern period, appears to have a face within in its circular centre, which reminds me of the sun in the ‘Teletubbies’!

The other smaller seals attached to the documents act rather like signatures of the commissioners, giving the document personal validation. However, these may not all be strictly personal seals. For example, the usage of simple iconography, like a cross patty with no personal seal legend, is evidence of this. Also one small seal simply reproduces the centre of the sun from the common seal.

Example of a cross patty; the reproduction of the common seal for personal use; potentially John Barbour’s personal seal (catalogue reference: E41/129; E41/130)

Round the edge of the Common Seal, the legend reads OMNIVM PRODUCTORV[M] DEVS EST CAVSA, meaning ‘god is the creator of all produce.’ This pictorial union of god and crown demonstrates the authority with which the commissioners exercise their role.

In my research I found an additional commission dated 1522 where all of the same commissioners were named. This earlier document explained that the commissioners were to be surveyors of mines in Devon and Cornwall, paying a twelfth of the gold and silver ore extracted to the king and a tenth to the owners of the land. This suggests that in 1536 John Barbour had been committing fraud, which would explain his replacement in the later document.

I had little prior knowledge of this most traditional industry in Cornwall and Devon. The document, which on first sight seemed terrifying, became the basis for my project, and dare I say by the end this manuscript was even more interesting than Poldark himself!

Even though I only have a brief understanding of seals and their meaning, this project has served as an introduction to them and has revealed something of their true value to me. Seals are miniature windows into the past, creating a personal connection to the people and places of history; they are so often unnoticed. The National Archives has tens of thousands of wax seal impressions, including those of monarchs, government departments, royal officials, as well as ordinary men and women from the medieval and early modern period.

To start your own journey into the wonderful world of seals, look at the seal card index in the Map and Large Document Reading Room and the seals research guide.

I really enjoyed reading this. I found the language very accessible as well.

Fascinating blog – thank you so much for sharing this.

Fascinating and lively… a real eye-opener

I really loved reading this and I’ve learnt so much. Great piece of writing. Thank you!

good.afternnon.national.argive.thank.so.much