In the first half of 19th century, science was mostly about observing and collecting. Huge sets of numerical data and collections of natural specimens were amassed, and sometimes plotted on maps or isoline charts[ref]An isoline is a line on a map connecting points having equal incidence of a specified meteorological feature.[/ref], or tabulated. It was guided by a paradigm inspired by scientific explorer Alexander von Humboldt: an ‘accurate measured study of widespread but interconnected real phenomena in order to find a definite Law’.

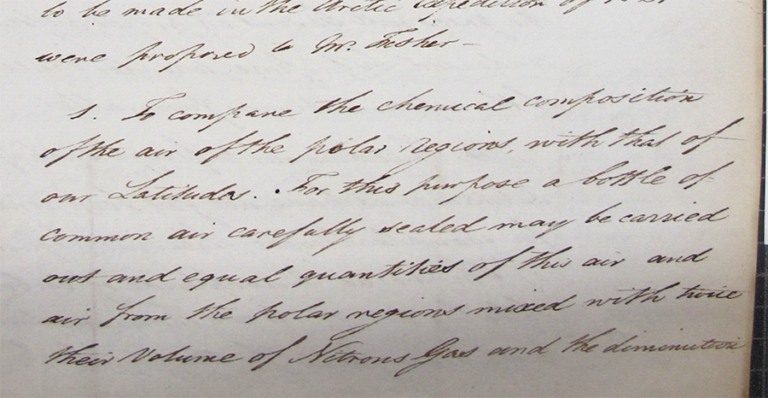

However, there was an amateur tradition in British science, to conduct or support such large-scale scientific projects as Humboldtian science, which involved high costs and many schemes, and was too complex for any private individual to organise. As can be seen in the instructions drawn up by the Royal Society for George Fisher, the civilian astronomer on board the Fury under William Edward Parry on his second voyage in 1821.

This meant that only the State, and especially the Navy, could afford to finance such ventures and provide large bodies of technically trained and reliable fieldworkers. All Royal Naval officers were taught to use and had practiced with precision instruments, and those engaged in survey work learnt to use more sophisticated instruments and mathematical techniques; all midshipmen learnt how to keep a journal, recording regularly and systematically phenomena such as latitude, longitude, bearing and wind direction. Humboldtian science seemed to be in line with much of the Navy’s work in conjunction with hydrographical surveys or voyages of exploration.

Emergence of scientific specialisation in the Royal Navy

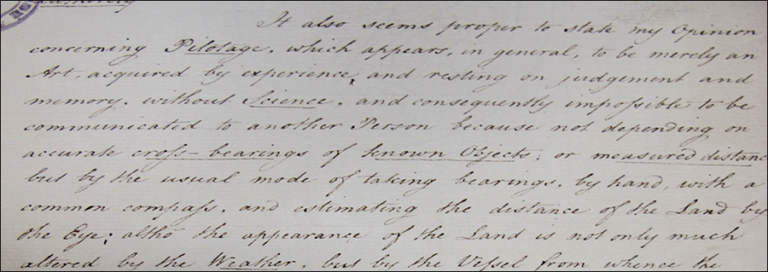

The emergence of a scientific profession in the Royal Navy can be seen in the Hydrographic Office, one of the scientific branches of the Admiralty, from the time when it was first established in 1795 under Alexander Dalrymple. During his time as Hydrographer of the British Admiralty, the office provided advice and suggestions on the importance of navigation science, as shown in Dalrymple’s letter to the Admiralty, reflecting the nature of surveying at the time:

‘…Pilotage, which appears, in general, to be merely an Art, acquired by experience and resting on judgement and memory, without Science, and consequently impossible to be communicated to another person because not depending on accurate cross-bearings of known objects…’

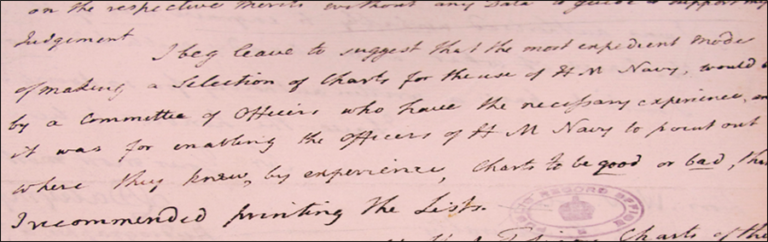

As a result, the Admiralty asked Dalrymple to make a selection of charts for production. Dalrymple had a long record of marine surveying experience, but it was mainly in the Far East where he had worked as hydrographer for the East India Company before, and he felt that he did not have enough experience in European waters. He therefore suggested selecting a group of officers tasked to produce a selection of charts for the use of HM ships. Hence the Chart Committee was formed – a group of naval officers including Captain Sir Home Popham, Captain Thomas Hurd and Lieutenant Edward Henry Columbine. During the time of Dalrymple as Head, the office devoted its time solely to the collection, production and issuing of charts for the Navy.

After Dalrymple left the office in 1808 and was succeeded by Thomas Hurd, the task of organizing hydrographic surveys was added to the office’s responsibilities. It became more professional, and specialised in maritime survey. The nature of the scientific work done on voyages of this period also began to change. Measurement of physical variables such as the earth’s gravity and its magnetism often assumed greater importance than natural history studies. This was in line with the general trend of the era, when science was leaning towards specialization into separated disciplines, coupled with the development of research programmes and the revival of physical sciences such as geophysics, astronomy, and mathematics, which seemed to complement the skills of naval officers.

These scientifically inclined naval officers played a very significant role in promoting physical science, as they were more at ease with investigations of this type; they assumed an increasing share of the scientific work rather than relying upon accompanying civilians. Under Thomas Hurd, the core of scientific naval officers, many of whom were associated with the Admiralty Hydrographic Office, took an increasing pride in their scientific achievements and sought recognition in the scientific community.

The Navy’s role and involvement in scientific activities

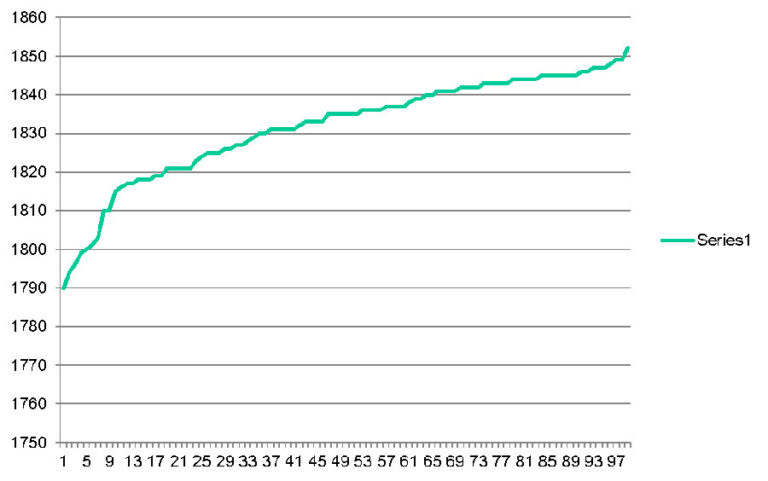

I have analysed and created a database for the Admiralty logs and journals of 99 ships on exploration and surveying held at The National Archives for the period between 1790s and 1850s, which covers from the time when Alexander Dalrymple became the Admiralty’s first Hydrographer in 1795 to Francis Beaufort’s retirement in 1855. I deliberately selected this period as it represents a time when the Royal Navy was enthusiastically involved in scientific research, which in turn influenced the careers of Royal Navy personnel.

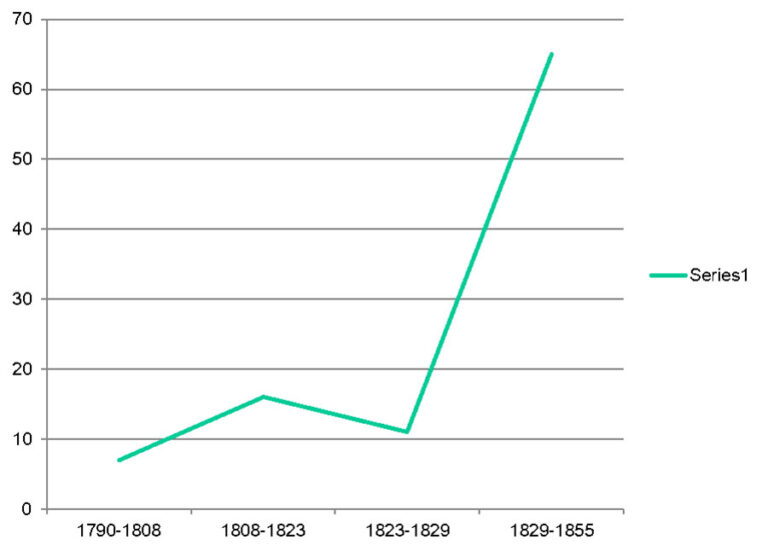

All the ships I analysed were involved in mostly scientific voyages in nature. My findings (as shown in graph 1 below) display quite clearly that there was an increase in scientific activities. At least 16 such voyages of surveying and exploration were organised during the Thomas Hurd period, as this task was added to the office’s responsibilities from 1810. As opposed to the period prior to the turn of 19th century, when marine surveying in this country was a relatively young science and still relied on amateur hydrographers who led a start in organising a survey of British coasts – Murdoch Mackenzie and his nephew Lieutenant Murdoch Mackenzie and Graeme Spence, for instance, who surveyed Kentish Knock.

Most of the scientific officers were elected fellows of the Royal Society during the time of Thomas Hurd as Head of the Office, and two of the group, William Edward Parry and Francis Beaufort, served as Hydrographer to the Navy.

William Edward Parry was appointed Hydrographer in 1823. He had ambitions to build the Hydrographic Office into a general scientific department of the Admiralty, but he faced strong opposition from the civil administration, most notably from John Wilson Croker, the First Secretary to the Admiralty. The growth of the nucleus of trained professional servicemen with scientific ambitions within an increasingly powerful Hydrographic Office was perceived as a threat by Croker. In addition, the Admiralty Secretary was under financial pressure in the 1820s, and the expansion of the Hydrographic Office ran counter to this policy.

Parry twice made the fatal mistake of leaving his post in order to lead scientific voyages. The first time, as he was on his third polar expedition, the department was reorganised in his absence; luckily for him, no naval chief was appointed to backfill his post. Similarly, after he returned from his voyage to reach the North Pole by boat, he found out that Croker had, once again, embarked on reorganisation and cost-cutting measures. Graph 2 below shows a drop in the activities of the Hydrographic Office between 1823 and 1829.

Faced with these attitudes and seeing no prospect of conducting the duties with advantage to the service, or credit to himself, Parry resigned his post. Parry’s view of the Hydrographic Department was ‘that it made him the Director of Chart Depot for the Admiralty, rather than the guide or originator of Maritime Surveys’.

However, no matter how much enthusiasm there was among the Navy personnel for scientific activities, there was rarely enough to establish a cognitive identity nor the institutional arrangements needed for devotees to cultivate their mutual interests. Scientific officers welcomed a forum in which they could feel socially at ease in indulging their scientific tastes with a group of associates, who would provide active support for the scientific conduct of their official ventures. Emergent reform groups, such as the Astronomical Society or the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS), provided such a forum.

The same applied to civilian reformers. They saw the scientific servicemen as their allies in scientific research as they were ideally trained and well placed to promote the pursuit of science. They were also able to provide support and bring such ventures to the attention of the government.

The alliance was to bear fruit in the 1830s when Francis Beaufort, in his capacity as Hydrographer, placed naval material and officers at the disposal of the new elite in their geomagnetic fact gathering. It was also in the interest of many scientific servicemen to ally themselves with the reform groups. If the reformists could gain control of institutions such as the Royal Society, they might form an important lobby for placing ventures like the Ordnance Survey and the Hydrographic Office upon a firm scientific footing, and create an institutional matrix in which scientific servicemen would not only be tolerated as facilitators but welcomed as participants in scientific research.

The influence of scientific reform on the career of scientific servicemen in the Royal Navy can be seen from the moment Francis Beaufort became Hydrographer in 1829. As a young lieutenant in the navy, Beaufort felt that further promotion was blocked by the system of parliamentary influence and corruption. He took the course of making a reputation as a hydrographer.

From 1812, he spent his time completing and annotating his charts of the coasts of Turkey and Syria for the Hydrographic Office and writing up his travels into a book, published as ‘Karamania'[ref]A contemporary European term for the shores of southern Turkey, where Francis Beaufort commanded the frigate Frederikssteen to explore. After returning to England, Beaufort set about drawing up the charts of his survey and documenting his findings, publishing ‘Karamania, Or, A Brief Description of the South Coast of Asia-Minor and of the Remains of Antiquity’ in 1817.[/ref].

Thereafter, he became increasingly active in metropolitan scientific affairs as a fellow of the Royal Astronomical and Geological Societies, and identified himself with the reformist cause. During his tenure, the Hydrographic Department became a large, efficient and relatively autonomous body conducting numerous surveys around the world.

In the 1830s, the interest in terrestrial magnetism developed on an international scale due to an increase in the use of iron in the construction of ships and to a general interest in the earth and its environment associated with Humboldtian science.

Beaufort played a prominent part in most of the major research programmes during the second quarter of the 19th century; the biggest and most expensive of them was the ‘Magnetic Crusade’.

Magnetism had featured prominently in the research programmes of the Royal Navy’s arctic expeditions since Sir John Ross’s first voyage in 1818, and interest was stimulated further by the discovery of the North Magnetic Pole in 1831 by James Clark Ross during his four years in the Arctic with his uncle, Sir John Ross. In this ‘magnetic fever’, Alexander von Humboldt was a prime mover together with Carl Frederick Gauss and Wilhelm Weber. Both were physicists from the University of Gottingen, and were actively improving instrumentation and setting up protocols for simultaneous observations worldwide.

The initiative was taken by the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS) in 1835, when it resolved that representations should be made to Government for the dispatch of an expedition to the Antarctic regions, for the purpose of making observations in various branches of science, such as geography, hydrography, natural history and especially magnetism with a view to determining precisely the place of the south magnetic pole or poles, and the direction and inclination of the magnetic force in those regions. The Royal Society took up the idea and Edward Sabine, F.R.S., a powerful figure in both the Society and Association, became the main driving force behind the eventual departure in 1839 of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror to the Antarctic under the command of Captain James Clark Ross, F.R.S..

A range of scientific activities, such as surveying and discovery, could provide distinct opportunities on the voyages for individuals to make some kind of scientific career for themselves either within or in association with the Navy.

Very interesting. The graph shows activities from 1790 but the HO did not commence until 1795.