Related event: Saturday 9 June 2018, 12:00

Related event: Saturday 9 June 2018, 12:00

Behind the scenes: conservation studio tours

The Collection Care department is offering a rare opportunity to go behind the scenes for International Archives Day on Saturday 9 June. Conservators and conservation scientists will demonstrate how they care for our nation’s history. Specialist areas will include paper and parchment, photographs, wax seals and our exhibitions and loans programme. Here are three conservators who will be there on the day, talking about why conservation matters to them.

Jacqueline Moon

I care for The National Archives’ collection of around eight million photographs. I’m an artist, but I trained to be a conservator in 2008. I want to protect the methods that have been used to make photographs so that future historians, artists and chemists can reinterpret the past. As a chemist, I might ask myself how we can we slow down fading in early digital prints; as a historian I might consider what the Victorians found funny; and as an artist I’d look at the creative potential of black and white photographs of dockyard construction or cold war coastal surveys.

Historical images were usually black and white when they were made. Today they often look brown, yellow or orange, often because they’ve been affected by damp and pollution; these effects can be slowed by cool and dry storage conditions. I recently did a Master of Research in Heritage Science to study yellowing in black and white photographs. I wanted to know whether I could develop a colour measurement that non-specialists could use to diagnose the causes of yellowing. Using an electron microscope, I made images of silver particles at x150,000 magnification. The silver particles, just 500nm across, would fit into the width of a human hair approximately 1,500 times.

Jacqueline checking the condition of film negatives. Photographs by Boyce Keay and Jacqueline Moon.

Lora Angelova

My job as a conservation scientist is to understand what objects are made of, how they were made, how they degrade and how we can limit their deterioration. I might start an analysis of a set of documents to measure how fast their inks are fading when exposed to light: this would help us determine how long they can be displayed in a gallery, but also allow us to identify the pigments and dyes used, which can give us a glimpse into the working methods of the time.

I recently worked as a researcher on the Nanorestart project at Tate. Initially, I wanted to preserve art – especially modern and contemporary art, which poses interesting challenges in terms of conservation: the materials very new and diverse, and so are artists’ working methods and intentions. Nowadays I work at The National Archives and I really enjoy small, incidental glimpses into the lives of others – for example, the journals from Captain Cook’s ‘Endeavour’ journeys. It was exciting to read about the encounters with distant lands and peoples that the sailors describe, but it was also nice to be reminded of the daily minutiae: ‘no observations’ is a sure sign of the boredom a sailor can experience after months aboard a ship.

Lora and Solange discussing the repair of braided seal cords. Photographs by Boyce Keay and Jacqueline Moon.

Holly Smith

I’m a book and paper conservator. I make sure the documents in the collection can be safely accessed by the public. I’ve worked on lots of different documents at The National Archives from Shakespeare’s will to 19th century wallpapers. I think our cultural heritage provides us with a direct connection to our past: a single piece of paper can bridge a gap of hundreds of years and provides a tangible connection to people who have long since gone.

I recently worked on an album of prisoners who were admitted into Wandsworth prison in the 1870s. Each page has a short description of the prisoner accompanied with a mug shot. This brought these people to life: some of them were young children. The book was broken, with pages beginning to tear and fall out. I designed a new binding structure that could withstand repeated use, as hundreds of visitors look at this book in our reading room over time.

I’ve always enjoyed making things: clothes, bookbinding, ceramic tiles. My job allows me to clean items, mend tears, repair broken books and reconstruct missing parts. I can be creative in how I solve problems. Sometimes a conservation treatment doesn’t exist and I have to borrow ideas from other industries. I’m currently using agar – an ingredient used in dessert making in Asia – mixed with enzymes – used in the manufacture of washing powder – to remove some creased, brittle fabric designs from a book so I can repair them.

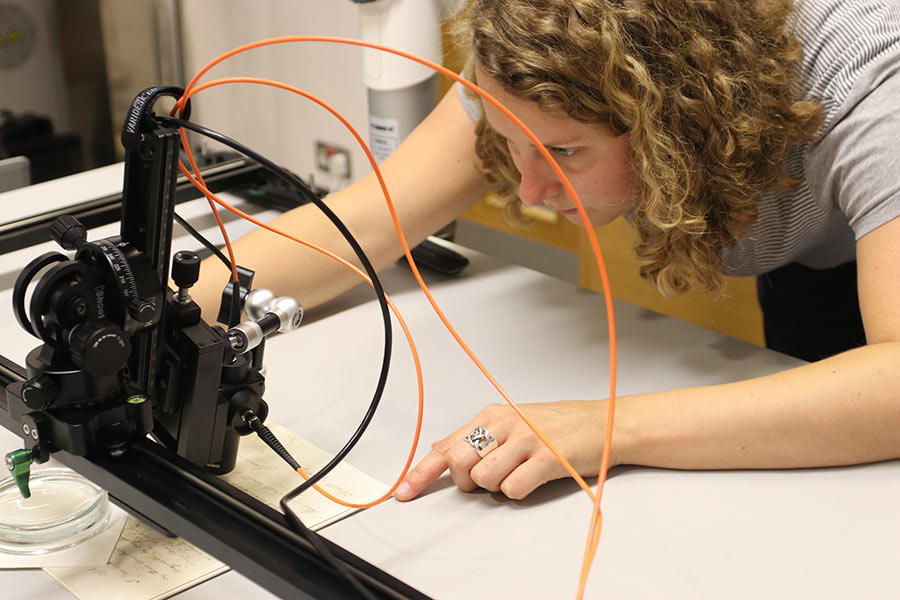

Holly testing the light fastness of Jane Austen’s will. Photographs by Boyce Keay and Jacqueline Moon.