Since the announcement last year that Prince Harry and Meghan Markle are to marry in May there has been much excitement and anticipation, with any number of news stories about the forthcoming wedding and speculation about virtually every aspect of it.

Excitement about royal weddings is not a new phenomenon, and documents at The National Archives show that, throughout history, it hasn’t just been the marriages of the heirs to the throne that have been the focus of attention. The weddings of their younger siblings, like that of Prince Harry, have also been major events.

Historically, weddings among the elite of society were much more about dynasty and diplomacy than they were about love. This was very much the case for the children of the reigning monarch, whose marriages could be deployed to strengthen alliances between the king and the leading nobles of his kingdom, or to forge ties with the rulers of neighbouring countries. In spite of this – or perhaps because of it – they were still occasions for great celebration.

This concern for dynasty can be clearly seen in the marriage of Margaret – second child and eldest daughter of Henry III of England and his queen, Eleanor of Provence – to Alexander III, King of Scots, in 1251, aged just 11 years old.

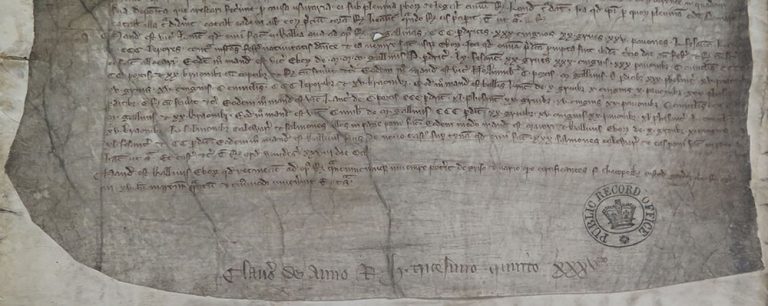

The great seal of Alexander III (reverse side) (SC 13/H22).

In the medieval period, Scotland and England were separate kingdoms, ruled by different kings. But, as next door neighbours, it was important to try and maintain good relations, and ties of marriage were one of the key ways of doing that. Not only did they tie the kingdoms together through the marriage itself, they offered the prospect that in the next generation, the children of such marriages would embody the Anglo-Scottish accord.

The marriage between Margaret and Alexander had first been agreed by their fathers when the couple themselves were mere infants. When Alexander’s father died in July 1249, the new king was still only seven years old, and thus far too young to rule by himself. Henry III was keen to secure influence in the group of Scottish nobles that ruled on behalf of the young Alexander III, and therefore pushed for the wedding to take place as soon as possible. The date was set for Christmas 1251, to take place at York.

The National Archives holds an incredible wealth of documents from the reign of Henry III, and these records reveal a huge amount about the planning and preparations for the wedding – the historian Kay Staniland counted about 130 different orders relating to the wedding among the records of Henry III’s reign.[ref]Staniland provides a full and illuminating discussion of the marriage in ‘The Nuptials of Alexander III of Scotland and Margaret Plantagenet’ in Nottingham Medieval Studies XXX (1985), pp.20-45. This volume is available in the Library at The National Archives. [/ref] Henry III was an affectionate father and doubtless wanted the wedding of his eldest daughter to go well for her sake. But it was also a major diplomatic occasion and nothing could be left to chance.

Used together with chronicle evidence, our records give us an amazing picture of this royal wedding that took place nearly 800 years ago. The chronicler Matthew Paris, who may well have been present at York for the nuptials, recorded that there was a huge number of magnates, knights and clergy from both England and Scotland ‘so that the serenity of so important nuptials might shine with greater lustre and extent’. In addition to the English and the Scottish nobles, Alexander III’s widowed mother, Marie de Coucy, returned from France with a retinue of French nobles to attend the wedding. It was a truly international occasion. Paris claimed that there were so many nobles in such great finery that ‘if it were described to the full [it] would produce in the hearer’s ears wonder and disgust’.[ref]Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora, v, pp.266-8 (Rolls Series 57). The Chronica Majora is available in the Library at The National Archives.[/ref]

Religious chroniclers were not beyond using hyperbole to make moral points, but the records held at The National Archives support Paris’s claims. The royal Chancery started issuing instructions relating to the provisioning of the wedding at the end of July. Vast quantities of livestock, game and fish were ordered to be sent to York for the wedding feasts. None of this was straightforward; livestock could be bought at markets, but arrangements then had to be made for the animals to be fed and cared for before it was time to slaughter them; game had to be hunted, taking account of the appropriate seasons; fish had to be caught and preserved; live fish were stored in purpose-dug ponds so that they could be caught and served fresh. From the Sheriff of York alone was ordered a thousand hens, three hundred partridges, thirty swans, twenty cranes, twenty-five peacocks, fifty rabbits and three-hundred hares; in addition to these he had to receive game from the seneschals of the king’s forests and arrange to get it all to York for the feasting.

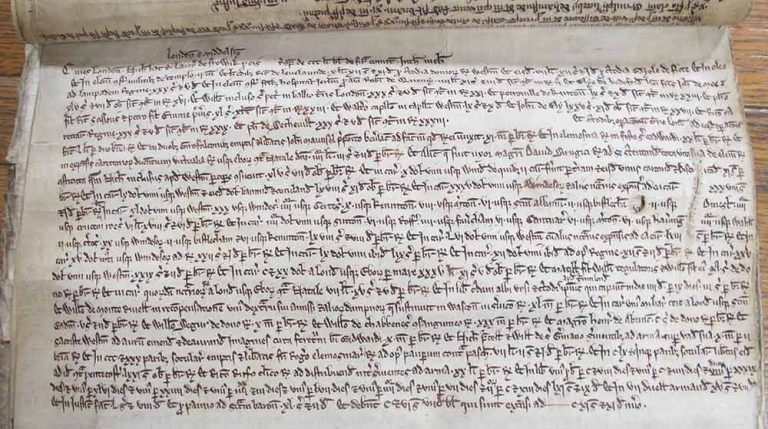

Orders on the Close roll to local officials for the provisioning of the wedding (C 54/64 m.1).

On top of all this fine food was the necessity to bake huge quantities of bread as well as procure spices, almonds and sugar. What never gets a mention is the procurement of fruit or vegetables – not because they were not eaten, but because they were grown on farms belonging to royal estates and therefore did not need to be bought.

Medieval wedding feasts required wine, and this was ordered in huge quantities. As with fruit and vegetables, ale was produced on royal lands, so does not get mentioned. But wine was another matter. The buyer of the king’s wines, a man called Robert Dacre, had the formidable task of procuring the necessary quantities, which involved not only purchasing wine from 11 different merchants but also arranging for it to be shipped from London by sea. In total, the wine cost over £200, which would be well over £100,000 in today’s money.

Part of the Pipe Roll account for London and Middlesex, including the payment of £35 11s 5 1/2d for shipping wine from London to York (E 372/96).

Aside from the feasting, the guests themselves were on show, and none more than the English royal family. Peter de Chaceporc, the keeper of the king’s wardrobe, and the king’s tailors had their work cut out to deliver all the required materials. New robes were ordered for Henry III and Queen Eleanor, and for Margaret herself and her two ladies-in-waiting. The heir to the throne, Margaret’s brother, Edward, was treated to a new tabard and tunic, as were his companions. The order on the close roll stipulates that the tabards are to be decorated with the king’s arms, and made of cloths of gold ‘if they can be found; if not, of scarlet, with leopards of golden skin… and Edward’s tabard should be furred with miniver, and the others with convenient fur, either of hinds or squirrels’. In addition, Henry III also paid for numerous gifts for the bride and groom, including robes, jewellery, beds, and trunks to carry it all in.

Despite the careful planning there were still hitches. There were so many guests that there was a shortage of accommodation – and fights broke out between the English and Scottish marshals who were looking for lodgings for their lords. The officials of the two kings present and of the Archbishop of York had to step in to curb arguments that broke out between the nobles themselves, as well as between their servants. Emotions were clearly running high.

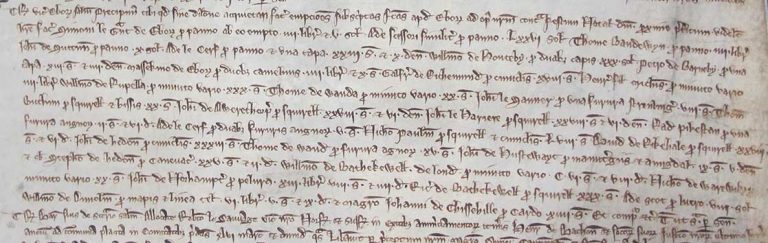

Payments recorded on the Liberate roll to numerous fur merchants, for furs bought for the wedding (C62/28 m.13).

Just like royal weddings now, the wedding was also the subject of huge public interest. The arrival of so many nobles, including the kings of both England and Scotland, caused a great stir in York and the surrounding area. According to Matthew Paris, there were concerns that the sheer number of ordinary people wanting to see the wedding would cause dangerous overcrowding in the narrow streets. As a precaution against accident, the wedding took place in the morning, earlier than originally planned.[ref]Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora, pp.267-8.[/ref]

In some aspects, however, medieval royal weddings were very unlike their modern equivalents. On the day after the ceremony, Henry III committed himself to pay 5,000 marks to Alexander III as the marriage portion of his daughter. A few days later, the English king pardoned a number of men who had been outlawed for murder, after Alexander’s intercession on the occasion of his marriage.

We have no records to shed light on what young Margaret may have thought about her grand wedding, or indeed about the prospect of becoming queen of Scotland. But as the eldest daughter of the reigning king, Margaret would have been brought up with the knowledge and expectation of making a diplomatic marriage at a young age, and at least she and Alexander III were about the same age and would therefore grow up together. Despite the move to Scotland, she and her husband stayed in close touch with her parents. Indeed, Henry III’s willingness to intervene in Scottish politics on the pretext of looking after the wellbeing of the young royal couple would cause tensions in later years.

But that was all for the future. The wedding day itself was a one of sumptuous feasting, of new clothes, of interested well-wishers, both high- and low-born, and of celebration and joy – illuminated even hundreds of years later by records at The National Archives.

Are there any drawings or paintings of the 11 year old married to the 9 year old?

Hello Elizabeth,

There are certainly no surviving contemporary depictions of the wedding. It’s possible that a later artist might have painted an interpretation of it.