As a contribution to our series of blogs on royal weddings, I have been examining some of our records on the wedding of Princess Elizabeth Stuart and Frederick V, Elector Palatine of the Rhine, on Valentine’s Day in 1613 at Whitehall Palace in London. Elizabeth went on to become the Queen of Bohemia and the grandmother of George I. Prince Harry is her 11-times-great grandson.

Princess Elizabeth, Queen of Bohemia and Electress Palatine; Frederick Henry, Prince of the Palatinate; Frederick V, King of Bohemia and Elector Palatine; by Simon de Passe, line engraving, after 1614; NPG D25750; © National Portrait Gallery, London; under a Creative Commons Licence

Elizabeth was the eldest daughter and second child of King James VI of Scotland and I of England. Born at Falkland Palace in 1596, she was just seven years old when her father and his family moved to England to take the throne. As was traditional with royal children, she was brought up in her own household – first at Coombe Abbey in Warwickshire and then, after the Gunpowder Plot was uncovered, in a ‘little house’ in Kew which was more accessible for the royal court.[ref]SP 14/62, f.24: Lord Harrington to Salisbury, 5 March 1611 – ‘in respect that this howse is lyttle’[/ref]

The choice of a spouse

As with most royal children, Elizabeth’s marriage prospects were the subject of considerable speculation and negotiation from an early age. Prospective suitors included the future King of Sweden, the Earl of Northampton, the future Duke of Savoy and the widowed King of Spain.[ref]Mary Anne Everett Green, ‘Elizabeth, Electress Palatine and Queen of Bohemia’ (Methuen, 1855), pp.25-29[/ref] The Gunpowder Plotters in 1605 also intended to make Elizabeth a puppet queen and marry her to a Catholic. However, it was the proposal of the Protestant Frederick V which ultimately proved successful, counterbalancing a possible Catholic alliance through the marriage of Elizabeth’s younger brother (the future Charles I).[ref]Nadine Akkerman (ed), ‘The correspondence of Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia’, volume I (Oxford University Press, 2015), p.9[/ref]

The first meeting

We know some personal details about Elizabeth and Frederick’s first meeting, four months before their wedding, from an account by Sir John Finet, Assistant Master of Ceremonies. This was published in 1656 and we have a manuscript copy of that publication which was made by one his 19th-century successors. Finet records that

The Count Palatine of the Rhine coming to marry the Lady Elizabeth … [was conducted] to the presence of The King, Queene, Prince, & Princesse, in the Banqueting House; where having made an humble reverence to His Majesty, & passed his first compliment, he addressed himselfe to the Queene, kissed her hand, saluted the Prince, & turning to the Princesse (who was observed till then not to cast the least looke towards him) he stooped to touch the lowest part of her Garment, when with her hand staying his, he received a kiss from her Highnesse, & soon after they all retyred to the privy Lodgings.[ref]LC 5/1[/ref]

The prospective bride and groom had corresponded before their meeting – but each was just 16 years old and they were, perhaps, understandably shy. [ref]See Nadine Akkerman (ed), ‘The correspondence of Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia’, volume I (Oxford University Press, 2015) for Elizabeth’s surviving letters to her future husband.[/ref] Their acquaintanceship developed over the coming weeks: John Chamberlain, a prolific correspondent of the period, commented that Frederick ‘takes no delight in running at ring, nor tennis, nor riding with the Prince… but only in her conversation…’ [ref]SP 14/71, f.34: John Chamberlain to Sir Dudley Carleton, 22 October 1612[/ref]

Preparations for the wedding

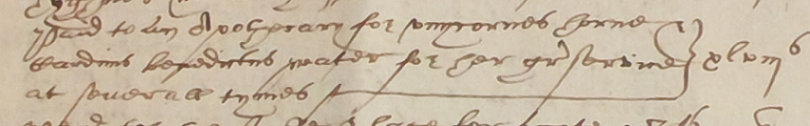

Elizabeth’s guardian, Lord Harington, kept accounts for Elizabeth’s household; when I read through those for the months before and immediately after the wedding, one entry in particular jumped out at me:

Paid to an Apothecary for unycornes horne & Cardius benedictus water for her gr[aces] service at severall tymes – xlviijs

Expenses of Princess Elizabeth: Lord Harrington’s account, 1613 (E 407/57/2)

This University of Cambridge blog suggests that ‘unicorn’ horn was probably derived from walrus ivory, rhinoceros horn or narwhal tusk, and featured as a component in anti-poison remedies. Perhaps its purchase is indicative of the heightened fear of assassination which must have been felt at court in the aftermath of the Gunpowder Plot. This atmosphere of fear is reinforced in Chamberlain’s letter to Sir Dudley Carleton, the English Ambassador to Venice, in which he commented on the extensive arrangements being made for security in the run-up to the wedding in the City of London, which ‘geves occasion to suspect that there is intelligence of some intended treacherie…’ [ref]SP 14/72, f.39: John Chamberlain to Sir Dudley Carleton, 11 February 1613[/ref]

The wedding was overshadowed by the death from typhoid fever of Elizabeth’s beloved elder brother, Prince Henry, in November 1612– but it was too important to be postponed for long. A further distraction from the celebrations was an argument over which foreign ambassadors had and, more importantly, had not been invited to the wedding.[ref]SP 14/72, f.50ff.: John Finet to Sir Dudley Carleton, 22 February 1613[/ref]

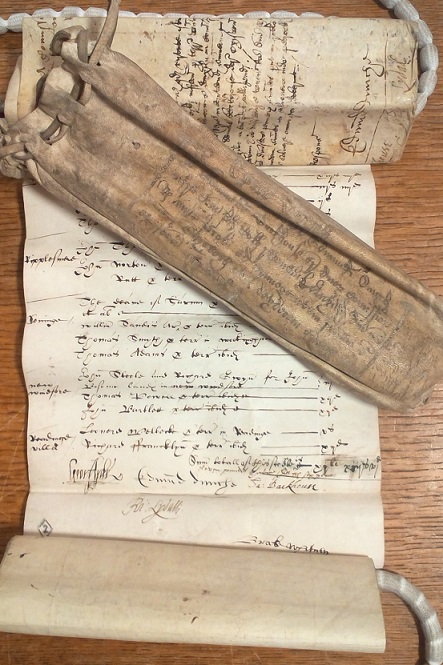

The expenditure on the wedding was, in part, funded by a feudal levy on freeholders which raised £20,500. However, this was not enough to cover the costs of the event, which came to some £53,294, plus a dowry for Princess Elizabeth of £40,000. [ref]Mary Anne Everett Green, ‘Elizabeth, Electress Palatine and Queen of Bohemia’ (Methuen, 1855), pp.58-59[/ref] This combined sum would have been enough to pay the wages of skilled tradesmen for nearly 1.9 million days, according to our newly-redesigned currency converter.

The names of three freeholders in New Windsor, Berkshire who defaulted payment of the levy towards the Princess’s marriage and the once-white leather pouch in which the schedule was stored (E 179/75/330)

Costs included at least £2,800 for a naval fight on the Thames the day before the wedding, which consisted of

five and thirty sayle of great pinnesses gallies galeasses carraques with great store of other smaller vessells so trimmed furnished and painted, that I beleve there was never such a fleet seen above the bridge, besides fowre floting castles with fire workes, and the representation of the towne fort and hauen of Argier [Algiers] upon the land[ref]John Chamberlain, SP 14/72, f.39[/ref]

Chamberlain reported that the King and court took little delight in this display, as there was little but shooting – and that several participants were severely maimed, including one who lost both his eyes and another who lost both his hands: a grim outcome for such a happy occasion. [ref]Frederick Devon, ‘Pell Records: Issues of the Exchequer during the reign of King James I’ (London, 1836); SP 14/72, f.39; SP 14/72, f.46[/ref]

Elaborate firework displays and masques were also held both before and after the wedding and, in anticipation of the onlookers being crowded together, farthingales (the hooped petticoats worn by ladies of the court) were banned. [ref]SP 14/72, f.47[/ref]

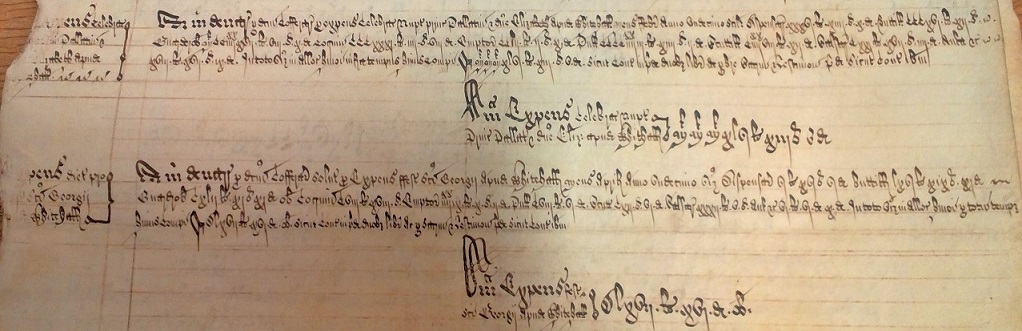

Declared Accounts of the Household: some of various large payments made towards the wedding preparations and celebrations (E 351/1808)

The wedding day

As with modern weddings, the dress of the bride was of particular interest. Chamberlain described the wedding day in a letter to Sir Dudley Carleton’s sister, Alice. In the following extract, the term ‘bravery’ meant ‘finery’ (or perhaps today we would say ‘bling’). He wrote,

the excesse of braverie, and the continued succession of new companie did so dasell [dazzle] me that I could not observe the tenth part of that I wisht. The bridegrome and bride were both in a sute of cloth of silver richly embrodered with silver, her traine caried up by thirteen younge Ladies (or Lords daughters at least) besides five or sixe more that could not come neere yt: these were all in the same liverie with the bride, though not so rich. The bride was maried in her haire that hung downe long, with an exceding rich coronet on her head (which the king valued the next day at a million of crownes).

He was more critical of the King’s outfit, though:

The king and quene both followed, the quene all in white but not very rich saving in jewells: the king me thought was somwhat straungely attired in a cap and a feather, with a Spanish cape and a longe stocking. [ref]SP 14/72, f.46v[/ref]

Finet noted in his correspondence that the jewels worn by the King, Queen, and Prince were valued at an astonishing £900,000 [ref]SP 14/72, f.50ff[/ref].

The days after

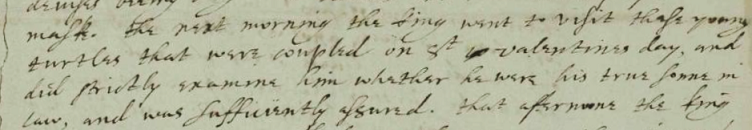

Chamberlain did not omit a reference to what we would expect to be the most private aspect of a wedding day – the consummation.

The next morning the King went to visit these young turtles [i.e. turtle-doves] that were coupled on St Valentines day, and did strictly examine him whether he were his true sonne in law, and was sufficiently assured.

State Papers Domestic: The King’s enquiry the day after the wedding (SP 14/72 f46v)

The celebrations continued for the next few days, with accounts of so many processions and masques that they left the King, and no doubt many of his courtiers, exhausted. Elizabeth, with her new husband, left England for a turbulent life in mainland Europe in April 1613; she did not return until her nephew had been restored as King Charles II. She died a few months later in 1662 and was buried in Westminster Abbey with much ceremony, but nothing to compare with the extravagant and sumptuous celebrations for her wedding nearly 50 years earlier.[ref]For articles on every aspect of Princess Elizabeth’s wedding, see Sara Smart and Mara R. Wade (eds), ‘The Palatine Wedding of 1613: Protestant Alliance and Court Festival’ (Wiesbaden: Harrossowitz, 2013)[/ref]

Thank you for the information. The bibliographic references to recent publications add a great deal to the primary materials.