From May 1940 British officials started interviewing foreign nationals or refugees arriving at British ports. The interviews were to ensure the refugee was not lying and therefore not a German spy. This arrangement was soon recognised as inadequate, and from November 1940 a more stringent process for verifying identities was put in place. The Royal Patriotic School (RPS), set up in a former Victorian asylum and First World War hospital in Wandsworth, started receiving alien refugees in January 1941.

The statements of these interviews are held at The National Archives in the series WO 208/3663-3748. Arranged by date, they record an individual’s name, and generally include date and place of birth, occupation and dates and locations of their travel to the UK.

Originally the records were maintained by the Home Office, using a reference of ‘AB’ (apparently the initials of the interviewer). M.I.9a then took over responsibility, with interviews still being undertaken at the point of entry by the Home Office. The interrogation number is the original Home Office number. If they were deemed worthy of further information they were then sent to the Royal Patriotic School.

The interviews were given an M.I.9a reference. M.I.9a later became M.I.19, an intelligence section of its own accord.

The interviews

Our volunteers have now catalogued the records, with approximately 4,000 refugees or civilians searchable by name, dates, occupation and places mentioned[ref]Where the date of birth is less than 100 years ago, the file is open, but the name and details will remain closed on Discovery. Details will be added annually.[/ref]. The records also include where maps, plans or photographs are included.

These records show the age and occupation of people entering the UK during the war. They don’t only include civilians, as interviews were conducted with deserters from the German army, Belgian and French air force and army officers, and merchant seaman. The ages range from 80 year olds to school children.

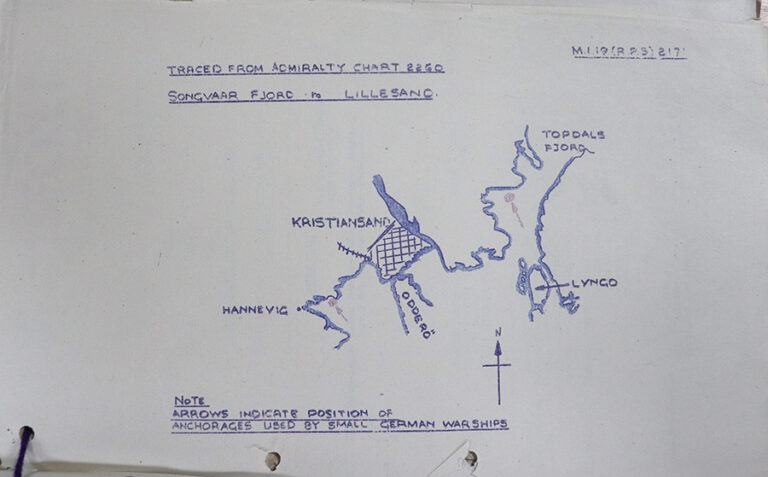

The records include maps and plans of various cities, towns, harbours and coasts around Europe, as well as sketched or traced maps of towns and coasts and drawings of items from boats, tanks, and German insignia. There are a number of reports of where large groups of refugees arrived. In 1941 HMS Castle Durham picked up a large number of refugees. Group interviews also include merchant seaman, fisherman, and groups arriving on small boats.

A large proportion of the interviews are of refugees arriving from Norway, travelling via Sweden or by boat directly to the UK. There are interviews with Norwegians brought back following the commando attack on Lofoten Island on 4 March 1941.

The cataloguing has also identified people escaping from the Channel Islands after the invasion and refugees who arrived in the UK via such places as Shanghai, New York and Brazil.

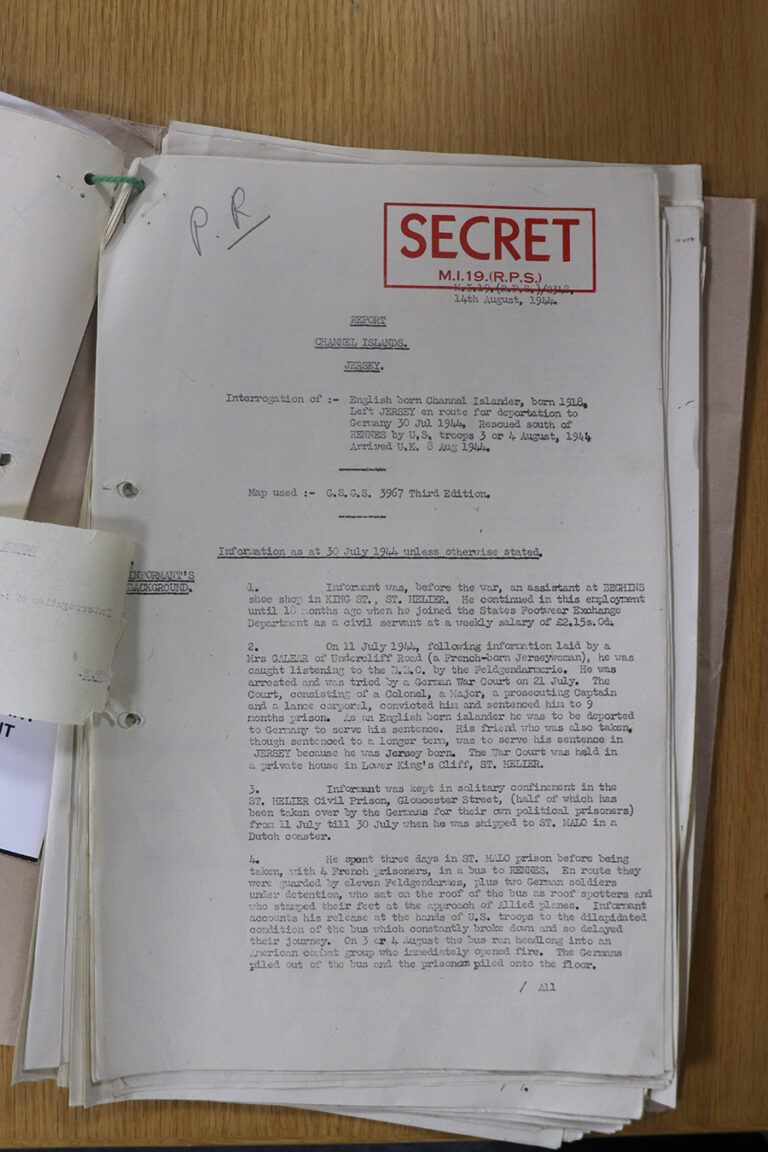

The report for one 26-year-old man reads: ‘In July 1944 he was arrested for listening to the BBC. He was sentenced to nine months in prison by a German war court on 21 July 1944. As a British-born Islander, he was interned and deported to Germany to serve his sentence. On 30 July 1944 he was shipped to St Malo, France, and then transported by bus to Rennes. The bus was a little dilapidated and kept breaking down. On the 3 or 4 August the bus ran into an American combat group, and he was transferred to British hands, and thus interviewed at Wandsworth’.

Deserters, POWs and escapees

A Soviet soldier, born in Gori, Georgia, deserted at Valonges, on 25 January 1944. He arrived in the UK, via Normandy, on 9 June 1944. The report starts by stating ‘although only numbering about 3,000,000, (the Georgians) are a people of culture far older than our own’. The informant recollects his time in the Russian army fighting against the Germans. He was taken prisoner of war in March 1942. In June he was recruited to the German army, 795 Battalion. In January 1944 he then deserted from the German army and, with the help of local farmers, was eventually picked up by an American soldier and sent to the UK. A later file includes a Captain in the German army who deserted, also from Georgia.

Other records include descriptions of how refugees travelled. Their journeys originated in countries outside Europe, such as Morocco and Singapore. Most journeys took the individuals through a neutral country, such as Sweden. Others made their way to the coast and hitched a lift on a merchant vessel. Some went as far as Brazil and Cape Town. One report states that refugees left Czechoslovakia and travelled to Italy, via Austria, then took a ship to Shanghai, then evacuated to the UK.

The records include stories of people escaping from prisoner of war camps and concentration camps. Two Polish soldiers are recorded as having escaped from Colditz, before making their way to the UK. One French engineer apparently escaped from Stutthof concentration camp. A further report is of an escapee from Stalag XII-D.

What’s next?

Our volunteers now plan to use this data to open the records in WO 208/5164-5170 and WO 208/5495-5506. These are arranged by number, although they are not a complete copy of the records in WO 208/3663-3748. The volunteers are also looking at cataloguing reports of POWs – both Allied and German – found in these records.

Come on these records should be open, if they are open to the public then they should be on Discovery, this is just data protection nonsense. What is to stop people publishing the names online?.

“Where the date of birth is less than 100 years ago, the file is open, but the name and details will remain closed on Discovery. … ”

There is a logical inconsistency here.

If data about people less than 100y old (in the absence of proof of death) is regarded as private, how can the items be open for research (revealing the names and details) but not open for indexing (because the names would be revealed)?

What professional advice has been taken to justify this contradiction and can it be published please?

A very interesting post, and one were I share the frustration of others who have commented on what is a potentially a mine of fascinating information – if only we have the tools to find the mother lode we are looking for and then the right shovel to unearth it!

I suspect that GDPR lies behind this and an/the answer lies in the 46 pages of the National Archives’ own document ‘A Guide to Archiving Personal Data’ (August 2018) which can be downloaded from https://nationalarchives.gov.uk/information-management/legislation/data-protection/ .

However, it would be very helpful if the author of this post could explain it to us in a jargon-free way, so that we can understand something that does seem very Orwellian.

As we have seen, writing about a new and exciting opportunity but then telling readers of this blog – most of which I assume will be users of archives without an archivist’s understanding of the policies and procedures that govern archives – that access to it will be less than straight forward and then giving only a ‘corporate’ explanation in a footnote is not helpful.

Section 70 of the Guide to Archiving Personal Data says that if the document is open the description should be opened. If you look at TNA’s Discovery catalogue there are overwhelming number of files of personal data that shouldn’t be open (as the people are or would still be alive. An example of living individuals are the Special Operations Executive personnel files. What TNA are doing is just another example of TNA stopping researchers researching.

Granting access to archival records under Data Protection law is a careful balancing act between making as much information available as possible in order to assist researchers, whilst being fair to the living people concerned – taking all circumstances into account.

Implementing Data Protection Law can be a highly technical process; the Guide to archiving personal data (nationalarchives.gov.uk), which was written for professional archivists, has to contain a lot of technical detail; as one of our respondents has noted. The Guide was written by The National Archives in collaboration with the wider Archival Sector, and with an endorsement from the Information Commissioner. The following section sets out the difference between personal data that is published online and personal data that is only produced in the reading room of an archive and is therefore much less exposed:

79. Careful consideration must be given to personal information in records that are to be made available online, especially if that information will be exposed to search engines. Placing personal data on a website, including digitised copies of manual [Paper, or other non digital] records, is different from processing paper records for onsite viewing, by its order of magnitude and greater ease of access. Data or digitised version of records should not be placed online unless their contents have been reviewed and it is fair to the data subjects to make the archives available in this way. It is possible that onsite inspection of paper records is fair because there is no way of searching by name, whereas online access would be unfair[and an unwarranted intrusion into their privacy] if there is searchable metadata [for example a catalogue entry] by name. In that case, those who come across the index data by using a search engine might not be aware of the archival context or age of the information.

The proposal to enhance the catalogue descriptions of the Royal Patriotic School Interrogations, in order to record other information such as individual, date and place of birth, and subject of report, was approved by The National Archives’ Discovery Board. The Board brings together experts from across The National Archives, including the Data Protection Officer, to review proposals and ensure that they are well-considered. It is chaired by the Digital Director.

In relation to these records, the Board decided that, given the subject matter and the fact that lists of these individuals’ interrogations have not previously been published, these items should be described beyond interrogation number and year of birth only, until the point at which the individual’s year of birth exceeds 100 years. The Board’s decision is in accordance with Section 70 of the Guide: ‘If the record is open, the description should be open but it must be fair, accurate and unlikely to cause substantial damage or substantial distress to a data subject’.

This collection comprises 87 records containing 2,600 interrogations. The bulk of these reports will be for people born before 1921, but as interrogations involved a number of students there may be a few hundred individuals in the collection born as late as 1927. Thus roughly three-quarters of this collection are already fully described on Discovery; as can be seen from the descriptions of the items in the first piece WO 208/3663. The shortened descriptions are reviewed on an annual basis, and any found to be of people born 100 years ago will be replaced with the full description. By 2028 they will all have a full description.

The catalogue entries have a number of errors, for example Brux is not in France but was in the Sudetenland (Czechoslovakia), it doesn’t say it was in France at all and Brux is well-known. The Dutch place-names have been mis-spelt (Rotterdam, Ijmuiden (transcribed as Ljmuiden), Eindhoven, Utrecht). I am sure there are many others.

David, we do endeavour to catalogue to 100% accuracy but as you can appreciate no cataloguing project is ever 100%. We catalogue as seen, and any misspellings or errors in the original document will be transferred to the catalogue. We cannot correct or assume a correction in errors in the document itself. Any transcription errors will be corrected if identified.

We do not ask our volunteers to be experts in geography, and in this case they have attempted to establish the country. [I personally had never heard of Brux]. An internet search finds Brux is a commune in France, and also the German name for a Czech town (Most). We will correct this, and remove France from the description.

This doesn’t explain unlisted pieces nor why two people (Bernard Karsenty and Andre Morali) have been listed 15 times each with different references each for the same document and one person (Wolfgang Frederick Paul Sperling) has four entries of which one is dated before he arrived in the UK. The cataloguing as seen never used to be the case under the old Editorial Standards, where it was evident it was with square brackets to indicate what it was believed to be true. References to Brux in the Sudetenland are in the files of the Nazi Persecution Compensation files (FO 950).