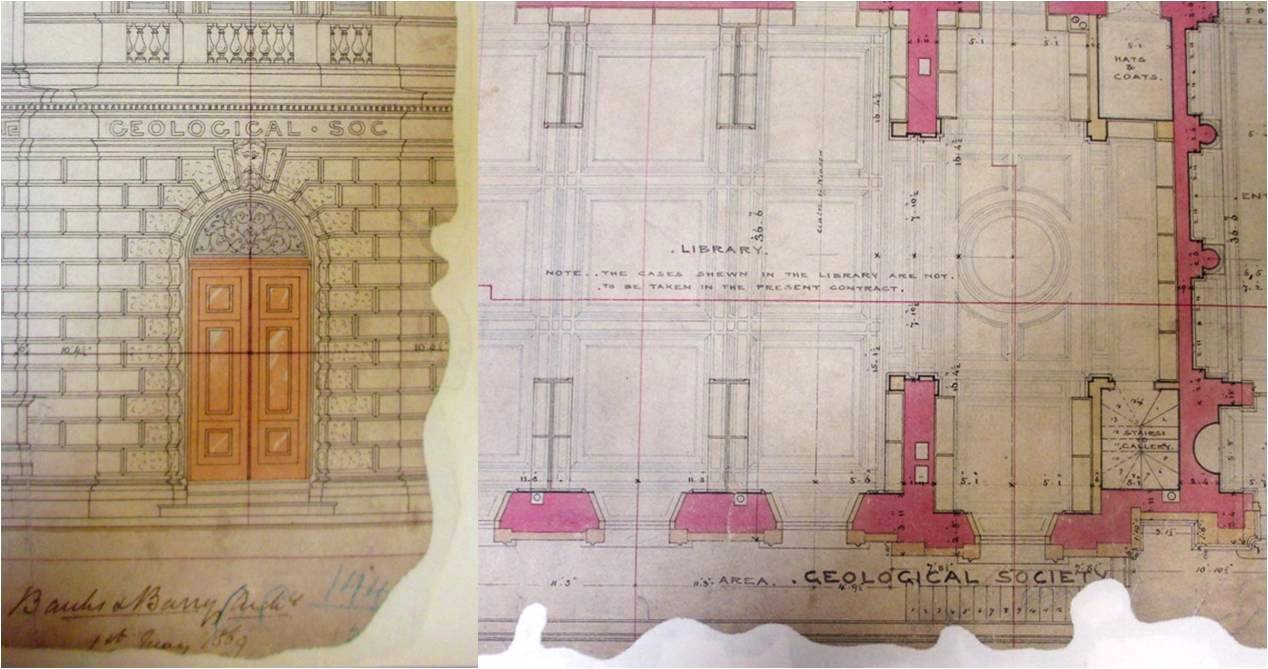

Details from architectural drawings of Burlington House in Piccadilly, central London, showing the Geological Society’s premises. References: WORK 30/535 (left) and WORK 30/602 (right)

I recently visited the Geological Society in central London as part of a tour organised by the History of Geology Group and the Charles Close Society for the Study of Ordnance Survey Maps. The highlight of the visit was a display of maps selected from the Geological Society’s library and archive collections. I enjoyed it so much that it inspired me to look at some 19th century geological maps from our own collections for today’s blog post.

Although we do not hold any discrete sets or collections of geological maps here at The National Archives, we do have quite a lot of maps that include some geological information. [ref] 1. Describing our holdings of maps as a ‘collection’ is a useful shorthand but really something of a misnomer: our records include both separate collections of maps and maps that are intermingled with textual records. [/ref] Some of these are in rather unexpected places among the records. For instance, I was initially rather surprised to find a geological map among railway records. [ref] 2. RAIL 1031/13[/ref] On reflection, though, I realised that this made sense: geological information can be extremely valuable when planning new railway lines.

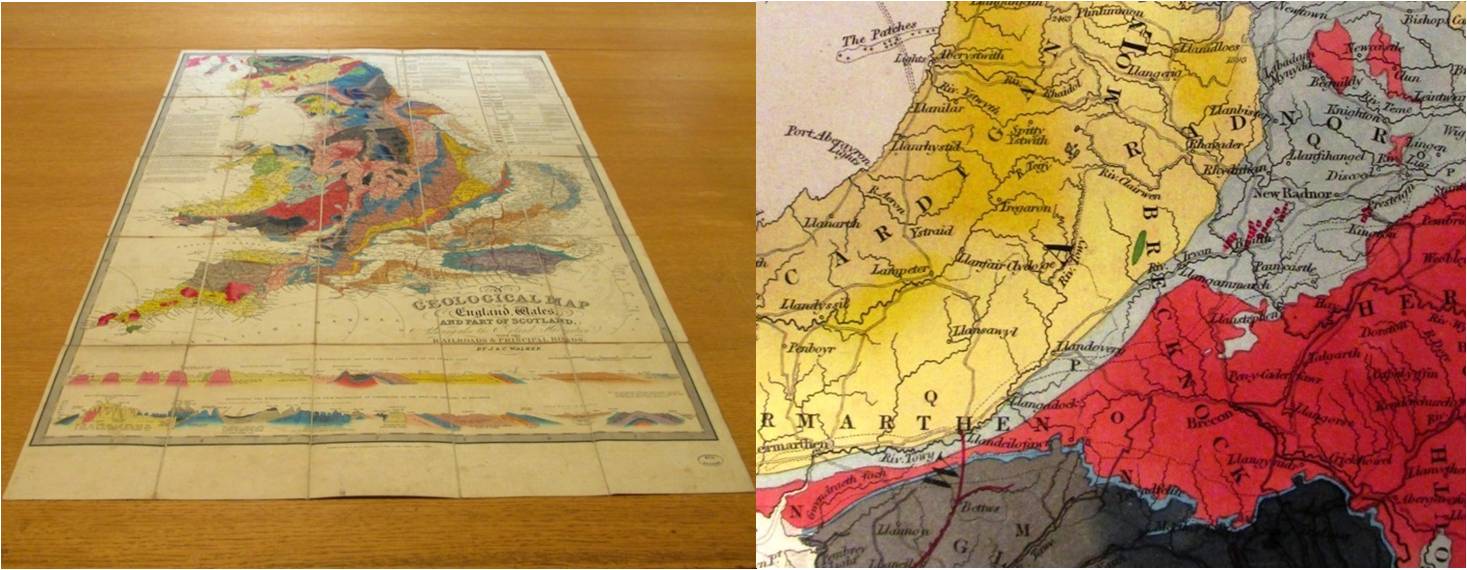

Left: This geological map of England and Wales, published in 1838, also shows railway lines and canals. Right: This detail from the same map provides an example of the bright colouring that has been a feature of many geological maps since the early 19th century. Reference: RAIL 1031/13.

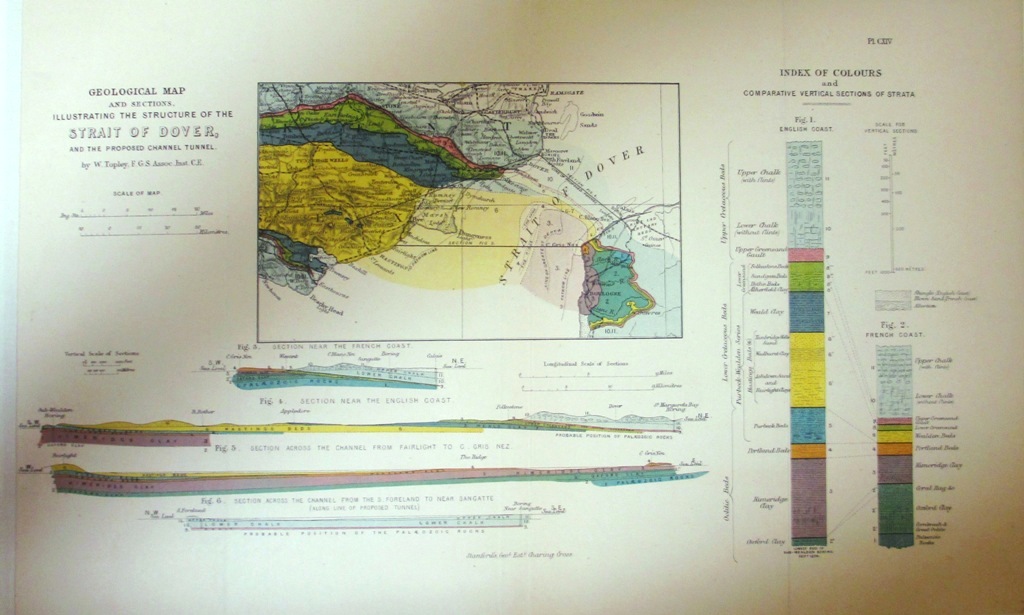

Another of our geological maps forms part of one of several 19th century proposals to build a Channel Tunnel between southern England and northern France. [ref] 3. MFQ 1/946/3 (map extracted from FO 27/2901) [/ref] It dates from about 1881 and comes from Foreign Office correspondence.

Like many geological maps, this one includes sections showing the different strata, or layers, of rock from the side. Reference: MFQ 1/946/3.

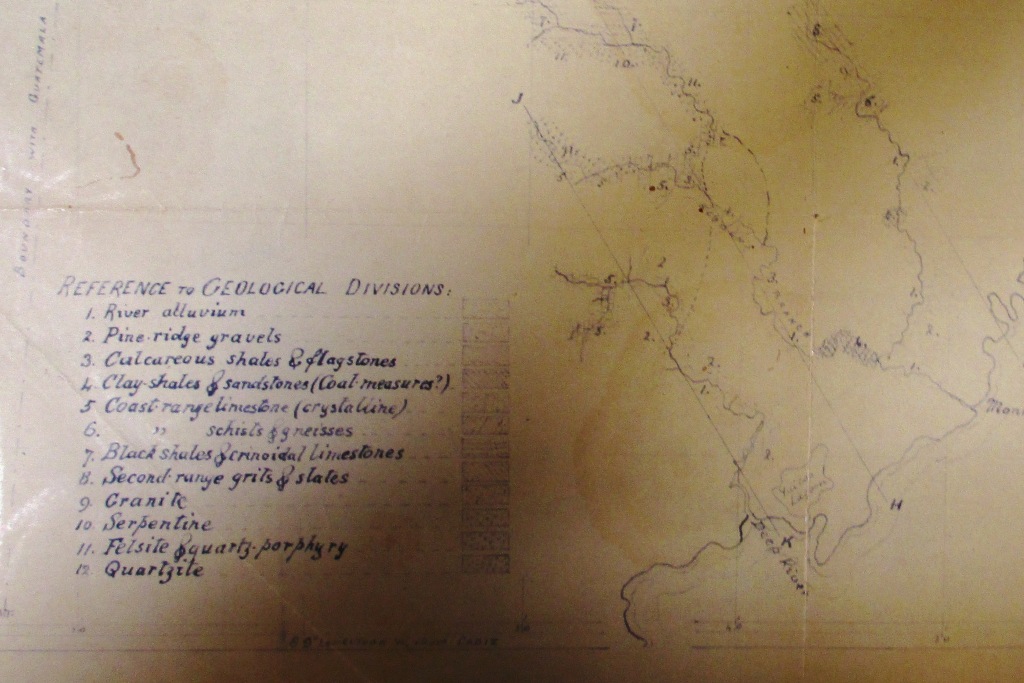

Some Colonial Office records include maps relating to the geology of former British Colonies. The example below shows part of British Honduras (now Belize) in Central America. [ref] 4. MFQ 1/196/9 (map extracted from CO 123/180) [/ref]

Not all geological maps are beautifully drawn and brightly coloured. This detail from a map of British Honduras, drawn in 1886, is more of a sketch. Reference: MFQ 1/196/9.

The final map I want to look at in today’s post is my favourite of the four. It comes from the War Office’s map collection and shows the Isle of Wight, off the south coast of England, and adjacent parts of the mainland. [ref] 5. MPHH 1/439/1 (originally WO 78/2153/1) [/ref] It is a Geological Survey map, consisting of a topographical [ref] 6. A topographical map is one that depicts natural and artificial features of the landscape. Most ordinary, general-purpose maps are topographical maps. [/ref] Ordnance Survey map, re-published with geological information added.

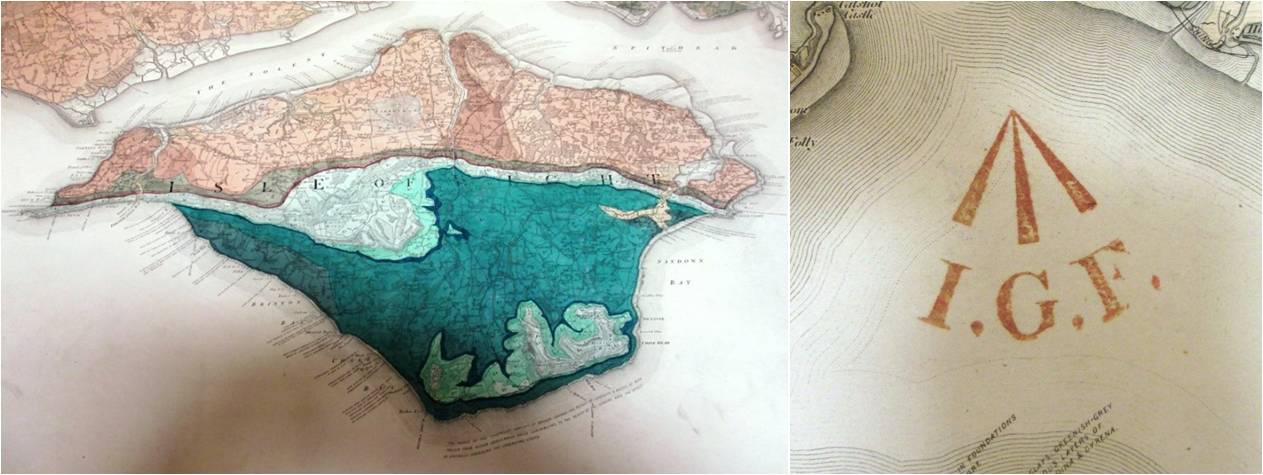

Geological Survey of England Wales 1:63,360-scale sheet X ('Ordnance Survey of the Isle of Wight and part of Hampshire'), published in 1856. The base map is the one-inch 'Old Series' sheet originally published in 1810. Reference: MPHH 1/439/1.

The Geological Survey was formally set up in 1835 to produce official British geological mapping. [ref] 7. See this page on the British Geological Survey website for more information about 19th century official geological mapping. [/ref] Originally, it was a department within the Ordnance Survey, but by the time this map was published in 1856, a separate organisation the Geological Survey of Great Britain and Ireland – had been established. This was the forerunner of today’s British Geological Survey.

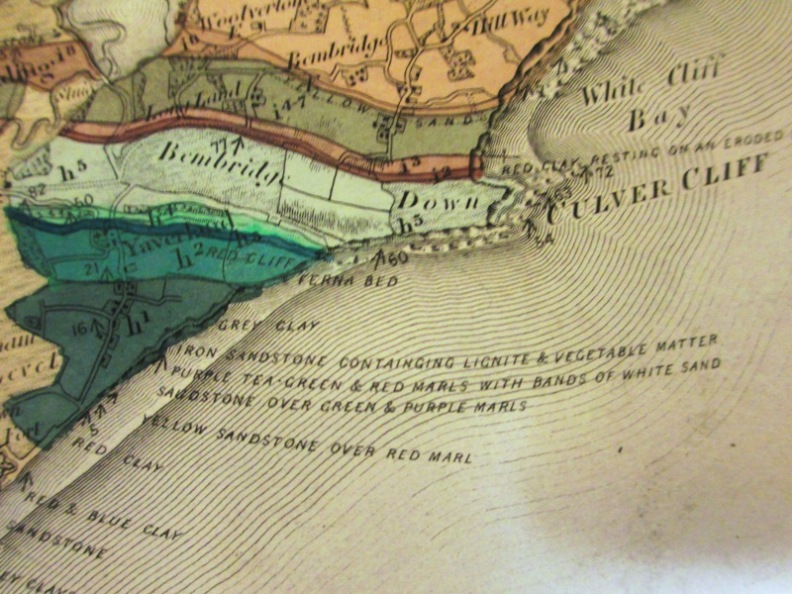

This detail of the area around Bembridge, on the eastern side of the Isle of Wight, shows a wealth of geological detail, both in the text and in the colouring.

Geological Survey maps like this one are of extremely high quality. [ref] 8. You can see this for yourself by browsing some more historical Geological Survey maps on the British Geological Survey website. [/ref] Both the topographical base maps and the added geological information were produced with the best available data and to the highest technical standards possible in the mid 19th century. The map was engraved and printed in black ink, with the colouring added neatly by hand. Colour printing techniques in the 1850s were not advanced enough to make printing a map like this in colour viable.

Left: A close-up of the Isle of Wight. Right: This stamp of the Inspector General of Fortifications makes our copy of the map unique. It was added when the War Office acquired the map, probably in about 1870.

Access to accurate mapping and other geological data can be vitally important to a wide range of organisations, from oil companies to universities, and to people working in a variety of professions, from civil engineering to environmental science. Yet, although geological maps are primarily practical tools, even those (like me) who have little knowledge of geology can still appreciate them for their appearance. For most people, it is their beautiful colours that make geological maps such fascinating objects.

It is often said that the best maps strike a perfect balance between science and art. We have many maps at The National Archives that illustrate the truth of this observation but, to my mind, geological maps offer some of the clearest examples.

The distinctive ‘piano-key’ border is characteristic of many 19th century Ordnance Survey maps at the scale of 1 inch to 1 mile.

You should not have been surprised to find geological maps amongst railway records. In many areas the excavation of railway cuttings exposed the local strata for the first time, particularly in areas with few outcrops.

Thank you for your comment, John. You are quite right: as I mention in the post, this shouldn’t have surprised me. (I should have taken my own advice and thought laterally before searching!)

Our ‘railway’ records include some records of canal companies too. Geology is obviously even more relevant to building canals than to building railways.

i really thought that it was great keep up the good work.

The Walker Bros map (RAIL 1031/13) is interesting. It is a late issue of this map – post 1839 – as the detail of central Wales you have included in the image shows Silurian geology (grey = Upper Silurian, yellow = Lower Silurian ) and the boundary between the red (Old Red Sandstone) is ‘indented’ rather than straight . This was all the work of the geologist R.I. Murchison who published his ‘Silurain System’ in 1839. If you look carefully you can see the earler geological boundary lines – which have not been engraved out – look for the parallel dotted lines.

There is an issue of this Walker Bros map (which is a reduced scale version of the ‘standard’ geological map they produced) with post 1839 geology in the collections of the National Museum of Wales, but it is dated 1842 (at the foot of the map) and I have not seen a copy of this map dated 1838 – so thank you for sharing.

Thanks for your comment, Duncan. It’s good to know that people are still reading and enjoying some of our blog posts months or years after they were originally posted.

Thank you for this blog, Andrew, which belatedly has come to my attention. I selected the maps and presented them for the HOGG/CCS meeting in 2013 and am pleased that to see where it has lead. Another source of geological maps at the NA are of the Forest of Dean. I think they are in the NA because the Forest of Dean was administered by the Crown. Are there other areas of Crown lands where there were mineral interests that the Crown would have geological maps, sections or records?

Thanks for your comment, John. I still remember what a great selection of material you chose for the visit.

There are certainly at least a few geological maps (including some of the Forest of Dean) among the maps in series F 17. http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C7210

I can’t recall seeing any specifically geological maps among Crown Estate records but I wouldn’t be surprised if there were some. There are certainly quite a few records relating to mineral interests. These search results give a flavour of what there is: http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/results/r?_srt=1&_st=adv&_aq=mineral&_cr1=CRES&_dss=range&_ro=any&_hb=tna