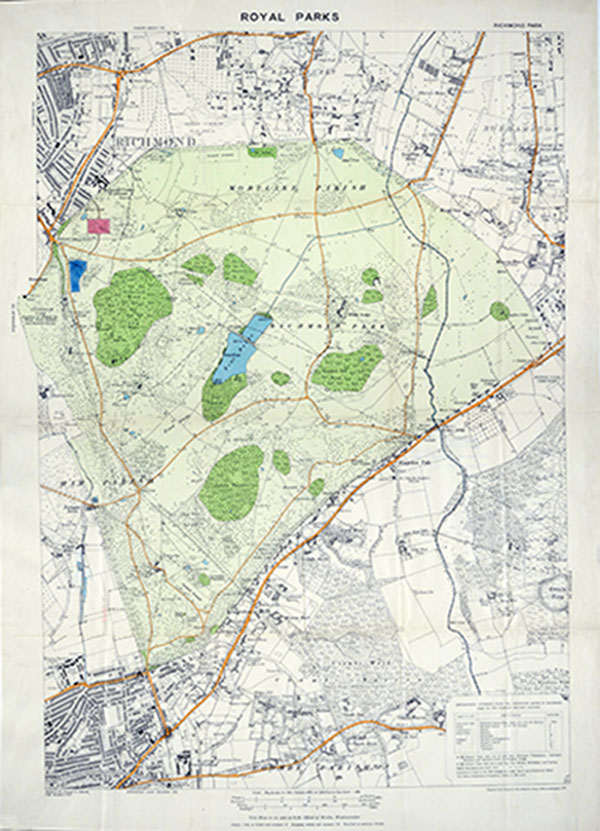

Map of Richmond Park showing the location of the South African Military Hospital

In August 1914, the Union of South Africa joined Britain and its allies in fighting against the German Empire. More than 146,000 South Africans fought during the First World War and a special hospital was built in Richmond Park for wounded South African soldiers.

The South African Military Hospital opened on 28 June 1916 on a site close to the Cambrian Gate in Richmond Park. Marked in red on the map (right), the hospital was opened after a prominent group of South Africans living in London formed a committee to raise funds for the establishment of a hospital, and for supplying general comforts to the soldiers.

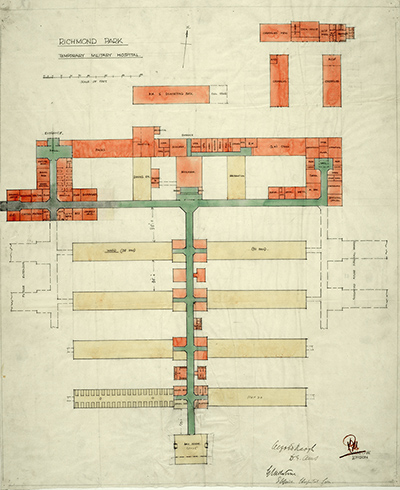

The whole of the building was built in a bungalow style. All of the corridors, wards and special departments were named after places in South Africa, to make those within feel more at home. For example, men from Cape Town were expected to feel comfortable in the short corridor named ‘Adderley Street’, after what is now the main street in the business district of Cape Town.

On entering, visitors were greeted by a spacious hallway, off which everything else connected. One of the most aptly named corridors was ‘Government Avenue’ where the Commandant, Matron, Adjutant and Paymaster were all situated. There were two dining halls – the ‘Mount Nelson Hotel’ and the ‘Carlton’ – both of which could seat around 100 people. There were four wards on each side of the main corridor and the day room at the end, where newspapers and games were provided.

Plan of the hospital

There were also a massage room, dressing station, and lab, as well as an x-ray department and operating theatres. A dentist’s office was provided – apparently the room dreaded by all. There was a designated ward for officers, a number of small wards for special cases, and two wards which were mainly used by those recovering from amputation. Special baths for the treatment of septic wounds were to be found on site – this ward was only the second of its kind to have been set up by this point in 1917, with the other being in Cambridge. There was also a dispensary, as well as various offices.

The patients’ emotional wellbeing was also provided for, with an excellent concert room with a stage, dressing rooms, footlights and the usual stage accessories. There was also a barber’s shop – a place where men could go and have a bit of a laugh and let off steam, as well as get their hair cut.

By the end of October 1918, a total of 274 officers and 9,142 men of other ranks had been admitted to the hospital.

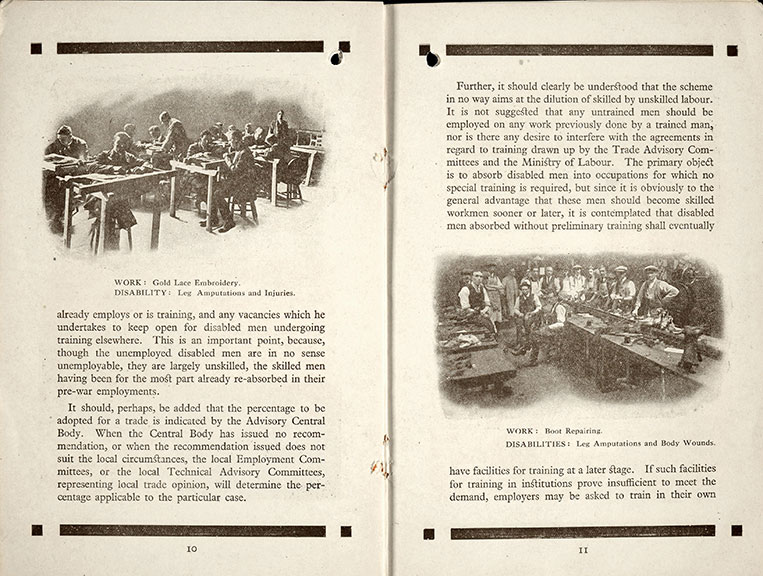

Two of the wards were intended for soldiers who had lost a limb. Treatment for these cases had to be introduced very early on at the hospital. Like many institutions at the time, the hospital set up workshops and training programmes for those disabled men who wished to go back into employment.

After negotiations with the War Office, construction of workshops began in November 1916. By early 1917, there was a carpenter’s shop, an electrical department, and classrooms on site. Soon, the men could take classes in becoming everything from metal turners and fitters to engine drivers; from switchboard operators to clerks. (If you’d like to read more about rehabilitation and employment for disabled First World War soldiers, this blog might be of interest.)

Image highlighting some of the work that could be undertaken in workshops

Although under the control of the War Office, the hospital managed to preserve its identity in that almost all of the staff came from South Africa. The medical staff consisted of 13 officers of the South African Medical Corps (SAMC) and 11 civilian practitioners who, for various reasons, were not eligible for commissions in the SAMC. The nursing staff belonged mostly to the QIAMNS Reserve or to the South African Military Nursing Service, and consisted of a Matron, two Assistant Matrons, 23 Sisters, 55 Staff Nurses and 88 probationers (most of whom were South African).

The ward orderlies were mainly non-commissioned officers and men of other ranks who had been invalided from the Front and were working at the Hospital while recovering their health and strength. The matron was Alice Purcell, whose service record can be found in our collections (WO 399/6809)

The hospital closed in 1921. Nothing really remains of it today, but if you go to Richmond Park and enter by the Cambrian Gate, it won’t take you long to be standing in the spot that the hospital once occupied.

Just outside the park gates in Richmond Cemetery is the South African Memorial opened by General Smuts. Also the graves of those who died in the hospital.

My Mother did voluntary work there, as a teenager !

The family lived in St.Margarets.

Her first love was there, but unhappily succumbed later, on return to the battle field.

My Grandfather was a patient there from 12 August 1917 – 8 February 1918. I am visiting the site 100 years later.

I have his diary which describes what happened to him and how he spent his time there, before his discharge back to South Africa.

All his official medical records (of which I have copies) match his diary entries.

Hi, out of interest where did you obtain his medical records? SANDF archives

Rgds Spencer

Re Spencer Kruger

Apologies for the delay in replying, have just seen this.

I got the records from a researcher the SANDF recommended to me. She has been a fantastic help and found out all sorts of info regarding my SA family history through their Archives.

Can anyone tell me how I can find out if my mother’s father was in that hospital where he then went on to meet his future wife.

I would like to know if medical records exist. My grandfather’s brother died at the hospital on 11 April 1921. He was in the Royal Navy and had been torpedoed twice during the war. First on HMS Triumph during the Dardanelles campaign and on HMS Marlborough during the Battle of Jutland.

He was discharged from the RN with a pension before the end of the war. He was a stoker on both ships.

William James Murray was buried in an unmarked grave in Richmond Cemetery. He was not South African but a South Londoner.

Hi Edward,

Thanks for your comment.

We can’t answer research requests on the blog, but if you go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts by email, live chat or phone.

Best regards,

Liz.

My great aunt, Gladys Priestley, was a Ward Sister at the hospital. I have photos and also a magazine article about the hospital which I am happy to share. And also letters from soldiers she nursed/their families/other nurses.

Hi Charlotte,

would your great aunt – by coincidence – have met Albert Marr of the SAI Brigade (October 1918), with his baboon Jackie?

Sincerely,

Dirk Danschutter

I HAVE IN MY POSSESION THE BRITSH WAR MEDAL GIVEN TO A MAUD HARRIET BRACKEN WHO SEREVED THERE IN WW1 ANY ONE HAVING IMFORMATION PLEASE CONTACT ME KIND REGARDS BEN

I’m researching and writing the bios of the 93 “Old boys” from my school, Dale College, in the Eastern Cape, who were killed or died of related causes during WWI. In the process I discovered that one of them, Zachary Booth Bayley, 41, Quartermaster, spent time at Richmond Park, suffering, not from a war injury, but from bronchopneumonia which he picked up in January 1917 near Arras where the South African Infantry Brigade were then posted. The hospital was previously unknown to me so its been fascinating to learn this facet of SA’s involvement in the war. Bayley was shipped back to SA where he died of his condition in 1919. He was and continues to be considered as a war casualty.

This site was later used in WW2 as a German POW camp and until the late 60s a WRAC (Women’s Royal Army Corps) camp. Nothing now remains of any structure and it has returned to nature.