Two hundred and sixty years ago, in the mid-summer of 1761, Richmond Park acquired a new Ranger. The previous holder, Princess Amelia, favourite daughter of King George II, had sold the office to her newly enthroned nephew, George III, in return for an annuity of £1,200 charged on land in Ireland. The King appointed John Stuart, Earl of Bute[ref]John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, served as prime minister from 1762 to 1763, and was arguably the last important favourite in British politics.[/ref] to the office on June 23. Princess Amelia purchased nearby Gunnersbury Park where she was known for her parties and political intrigues.

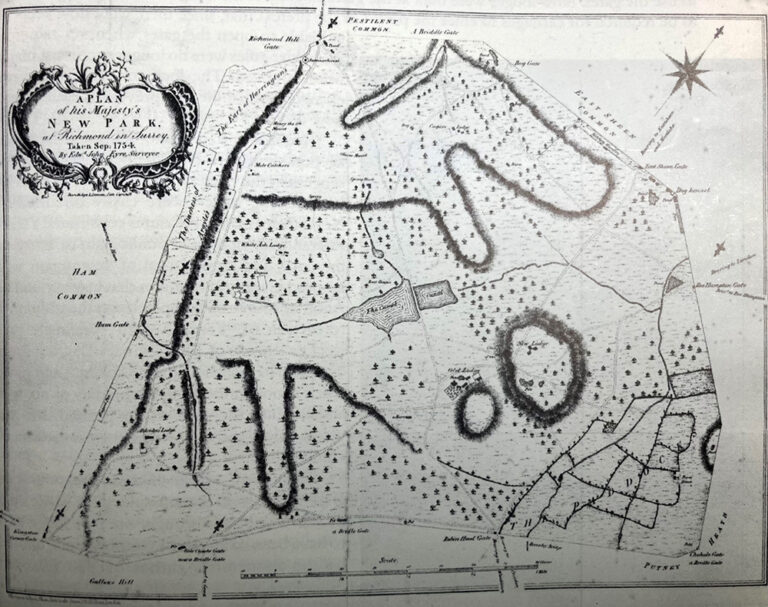

King Charles I had originally created his ‘New Park’ at Richmond in 1637 for the hunting of red and fallow deer[ref]Charles who was ‘excessively affected to hunting and the sports of the field’. M. Baxter Brown, Richmond Park: The History of a Royal Deer Park (London, 1985), p.18 (quoting from Clarendon, History of the Great Rebellion, Book 1). [/ref], enclosing (imparking) private lands in north Surrey from the manors of Petersham, Sheen and Mortlake. However, certain limited concessions were granted: the most significant being rights of way to enter through the park gates, and for the ‘commons’ to gather furze and underwood for fuel.

The first signs of restrictions on public access to the park became apparent during the rangership of Amelia’s predecessor Robert, Lord Walpole (son of Sir Robert Walpole, the Whig Prime Minister), and were largely associated with the deer herds, and their hunting with buck hounds. The Walpoles, both Lord Robert as Ranger in 1740 (and his father the de-facto Ranger during the 1730s[ref]Sir Robert Walpole went regularly to the Park at weekends to hunt and to stay at the Old (Hartelton Estate) Lodge, where he claimed he could ‘do more business than he could in town’. John Cloake, Palaces and Parks of Richmond and Kew, Volume II (Phillimore 1996), p. 108[/ref]), restricted public access to improve their own enjoyment of the park, which they came to regard as their own private estate, and at that time had a flock of some 3,000 wild turkeys which were raised as game birds[ref]During the Bute Rangership, both deer hunting and the raising of turkeys in the park for shooting would be ended under the directions of George III (who considered himself to be the ‘friendly squire’ of the people). M Baxter Brown, Richmond Park: The History of a Royal Deer Park (London, 1985), p. 80.[/ref]. Curtailing the rights of access that Charles I had originally left in place a century earlier, they removed a number of the ladder stiles[ref]Coombe Gate (later known as Ladderstile Gate) provided access to the park for the parishioners of Coombe, with both a gate and a step ladder. The gate was locked in the early 1700s, and bricked up in the mid-1730s under the directions of Walpole.[/ref], setting up lodges at the gates, with keepers who had orders to admit only ‘respectable persons’ on foot, and carriages with authorised entry tickets.

![15 September 1757, 'An Accompt’ of John Pitt regarding a warrant for the purchasing of ‘sixty eight brace’ [136] of male deer [bucks].](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/22105117/LR-4-8-7-1757-768x859.jpg)

The political diarist and antiquarian Horace Walpole, writing from nearby Strawberry Hill House, would comment in his memoirs that at the time of George I’s death (in 1727) the park was ‘a bog and a harbour for deer stealers and vagabonds’[ref]M Baxter Brown, Richmond Park: The History of a Royal Deer Park (London, 1985), p. 70 (quoting from Walpole, Memoirs of the Reign of George II).[/ref]. Neighbouring Wimbledon Common (which had been the old Medieval Half Moon deer park) was also a notorious haunt for deer stealers, poachers and ‘other’ robbers.

In the 1720s there had been an all-out poaching war in the South of England from, for example, Waltham Chase, the Forest of Bere and Alice Holt in Hampshire to Windsor Great Park to Enfield Chase in Middlesex and Epping Forest in Essex resulting from the repressive so called Black Act of 1723[ref]In response to a series of raids by two notorious groups of poachers, known as the ‘Blacks’. The Act which was passed in the aftermath of the South Sea Bubble collapse and the ensuing economic downturn, greatly strengthened the criminal code by specifying over 200 capital crimes.[/ref].

The infamous Thief-taker General, Jonathan Wild, was also connected with the murky underworld of poaching activity on the fringes of the Home Counties, where things had got so out of hand that in July 1725 it was suggested that foot soldiers be sent to Barnet to aid the local keepers (see SP 35/57/60). Between 1723 and 1725 there was also a mini-war between deer stealers and gamekeepers in Richmond Park that involved arson of keepers’ houses, and ‘diverse outrages and disorders’.

At least two poachers were sent to the gallows[ref]A Gallows Hill is shown on the outside of the park on Eyre’s 1754 map, which corresponds to Kingston Hill and the old Portsmouth coaching road.[/ref]. However, John Huntridge, landlord of the Halfway House Inn on the wall of the park near Robin Hood Gate, was more fortunate. He was charged with harbouring deer stealers after a warrant was issued to apprehend him for concealing Thomas James, who had been charged with the shooting of the gamekeeper Edward Fitzpatrick in Enfield Chase. The elder Walpole (as Chancellor of the Exchequer) backed the case against Huntridge, who was acquitted in November 1725 to much popular acclaim – the verdict being seen not only as a local matter, but as a stand against the corrupt system of patronage and legal extortion which the Walpolean era came to represent.

![1725 April: Directions from [the Secretary of State for the Southern Department] the Duke of Newcastle to issue a warrant to apprehend John Huntridge, regarding the shooting of Edward Fitzpatrick in Enfield Chase.](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/22105144/SP-35-55-125-144-768x627.jpg)

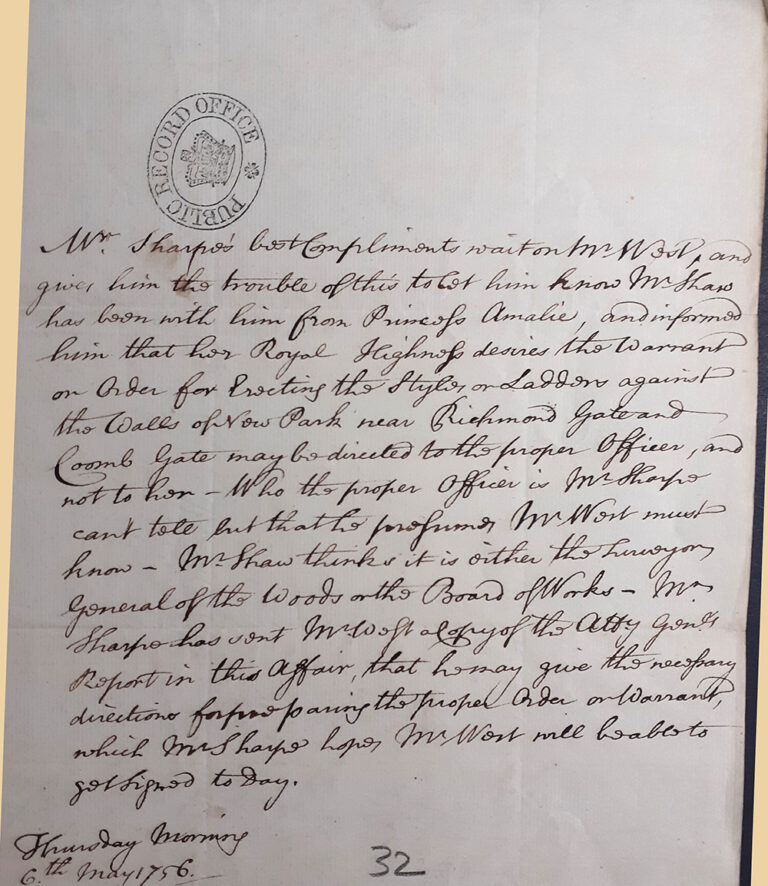

Shortly after her appointment in 1751 as Ranger of Richmond Park, Amelia reduced entry to the park even further, closing it completely to all but her personal circle of friends[ref]Even refusing admission to the Lord Chancellor, the Earl of Hardwicke.[/ref] by requiring prospective visitors to obtain special hard-to-come-by permits. She also blocked several old roads, such as the one from Kingston to Sheen that had served as a footpath, ignoring legal warrants for the placing of stiles and ladders near Richmond ‘Hill’ Gate.

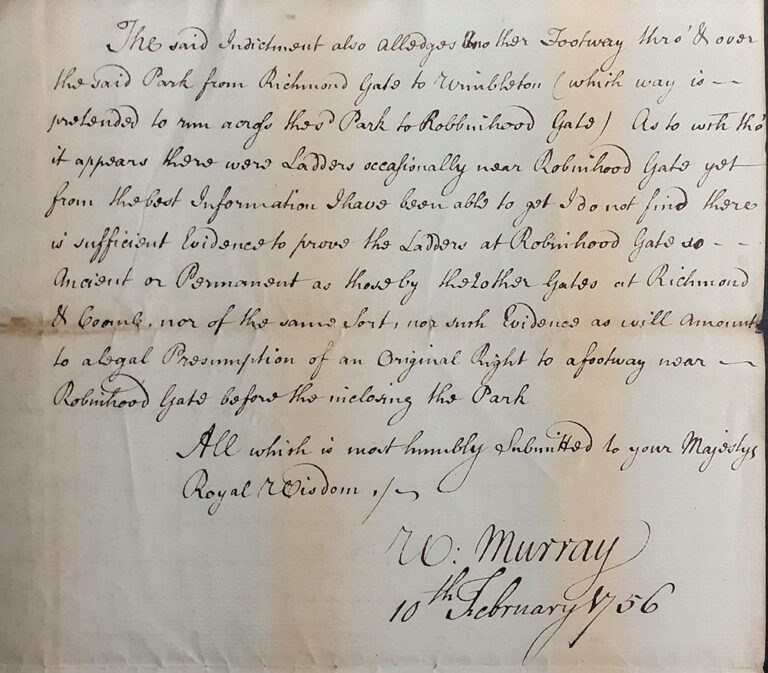

Amelia’s refusal, some six weeks after she had taken up office, to allow the traditional ‘Beating of the Parish Bounds’ ceremony under the direction of the Richmond churchwarden Thomas Wakefield, led to the so-called ‘Ascension Day Incident’ (of 16 May), whereby access was eventually gained (albeit with some difficulty) by clambering through a breach in the wall near Roehampton, the princess’s outnumbered park bailiffs being unable to prevent the action.

Amelia’s restrictions caused much inconvenience and resentment in the neighbouring parishes as political and legal opposition was launched in response. Having acquired a certain notoriety, which was duly reported in the popular broadsheet ‘The Post-Boy’, the Ascension Day ‘Trespass’ was in effect an assertion of the old manorial rights of access to common lands. The incident effectively began a campaign of agitation and judicial challenge throughout the 1750s.

Failure to win concessions by publicity and campaigning led to legal action and initial Court proceedings under the Lord Chief Justice Sir Dudley Ryder, after the Deputy Ranger Deborah Burgess (as ordered by Princess Amelia) had personally refused a group of gentlemen admission to the park. The shambolic Symmonds versus Shaw case which followed at Croydon Assizes was eventually thrown out of court in November 1754, after £1,095 had been collected for the right to cross the park by ‘perambulator or foot’.

The most celebrated case was that of Gray versus Lewis, after John Lewis, a Richmond brewer of the ‘middling sort’, and his friends were denied entry to the park by the keeper of East Sheen Gate, Martha Gray in 1755. The long-drawn out legal proceedings would culminate with the case of Rex versus Martha Gray in 1757, after Lewis served an indictment against the gatekeeper for their forcible removal from the park.

![1758, Rex v Martha Gray, ‘An Historical Account of the Inclosing [of] Richmond new Park in 1637’.](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/22105211/TS-11-444-1415-1-1758-768x896.jpg)

Basing his case on a narrow legal issue, Lewis shrewdly used the example of historical precedent with Charles I’s original granting of free passage through the park, which was reinforced by the post-Restoration writings of Edward Hyde, the Lord Chancellor Earl of Clarendon, whereby Rex as in ‘The King’ (Charles I) would prosecute Martha Gray. However, this litigation was initially adjourned after an anonymous pamphlet – A Tract in the National Interest – was shown to be a veiled attack against Princess Amelia herself. Following much legal wrangling, the case was finally heard at the Surrey Assizes sitting at Kingston-Upon-Thames for the Easter Term of 1758, where judgement was given in Lewis’ favour for pedestrian access to the pathways (albeit with ladder stiles rather than gates).

While Amelia, outraged at her defeat, failed to get the ladder rungs altered after ‘a vast concourse’ of neighbouring villagers climbed over into the park (some reputedly declaring it ‘now to be theirs in common’), a further court case in January 1760, which attempted to gain ‘ticketless’ entry for carriages, and the use of bridleways however, was not so successful. Although John Lewis, becoming something of a local celebrity, was burdened with considerable legal expenses[ref]Although a collection was organised for Lewis after his Thameside brewery by the Petersham Road was destroyed by severe flooding, he died a pauper in 1792.[/ref], he did achieve limited rights of way which established the principle of public access.

![1758, Rex v Martha Gray, ‘An Historical Account of the Inclosing [of] Richmond new Park in 1637’.](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/22105213/TS-11-444-1415-768x514.jpg)

The impassioned issue of public access to Richmond Park would only become less heated from the 1850s onwards, and culminated in the legislation of 1872 with the passing of the Royal Parks and Gardens Act, which ultimately marked a new approach to public ‘green space’ inclusion. Ironically, it was King Charles I’s very act of walling up the park in the 1630s which preserved an extensive tract of Greater London open space that became the National Nature Reserve for all to enjoy today.

John Lewis was my five times great grandfather. The basic details of his successful attempts to gain access to Richmond Great Park have passed down as oral history within the extended family and my father told me about them when I was a teenager. Both he and my grandfather were given “Lewis” as a forename in memory of John Lewis.

There is more information which can be added to your excellent account:

• Copies of a portrait of John Lewis painted by T Stewart and engraved by Robert Field are held by both the National Portrait Gallery and Surrey Archives.

• More details about John Lewis and the court cases appear in WAKEFIELD, Gilbert, Memoirs of the life of G. W. written by himself, 1792, London. This is available in The British Library. Wakefield described Lewis as “a patriotic man, endowed with an extraordinary portion of strong native sense and a fund of sarcastic humour.” In relation to the aftermath of the 1758 case, Wakefield wrote “In mere spite, the steps of [the] ladder were set at such a distance from each other, as rendered it almost useless. Lewis complained again to the court. ‘My Lord’, says he, ‘they have left such a space between the steps of the ladder, that children and old men are unable to get up it.’ ‘I have observed it myself’ says this honest Justice ‘and I desire Mr Lewis that you would see it so constructed that not only children and old men, but OLD WOMEN too may get up.’”

• Although John Lewis was a brewer of the ‘middling sort’, his brother William Lewis was a “celebrated chemist” and physician, a Fellow of the Royal Society and the Royal Academy of Stockholm. (See F.W. Gibbs M.Sc. Ph.D. (1952) William Lewis, M.B., F.R.S. (1708–1781) https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tasc20

• “From a state of affluence & distinction [John Lewis] fell into poverty in his old age”. This followed “one night [in 1774 when] the water in the Thames rose to a considerable height; the doors of the counting house of the brewery were broken open by the force of the water, & the various account-books, papers &c, belonging to the business, were washed into the river.”