As a lifelong resident of Richmond I have been surrounded by the remnants of a lost palace, hidden in almost plain sight, but like most others never given it more than a passing thought.

Since starting work at The National Archive ten weeks ago I have found myself drawn to the history of Richmond Palace and its importance over the last 900 years: where did this palace go and what happened there?

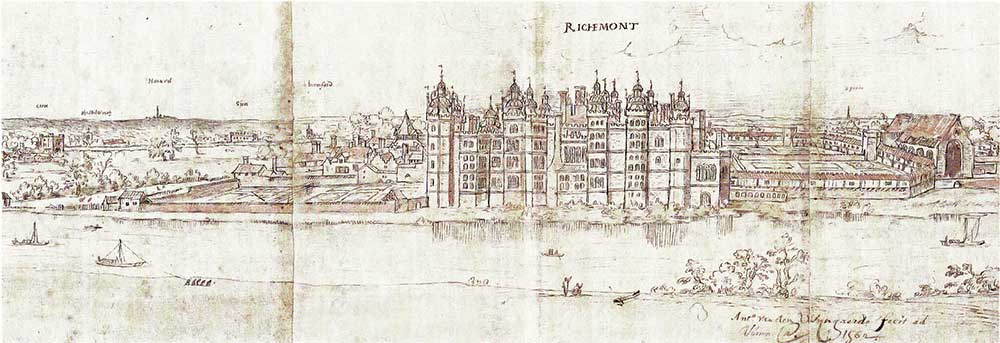

Richmond Palace by Wyngaerde, c.1558-62 (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

My aim in this blog is to follow Richmond Palace from its creation to its eventual destruction, and its modern resurrection, using the resources and veritable treasure trove of documents that chart its turbulent history. I’m attempting to help bring this palace back into the forethought of the public memory, in the hope others will look into this fascinating building.

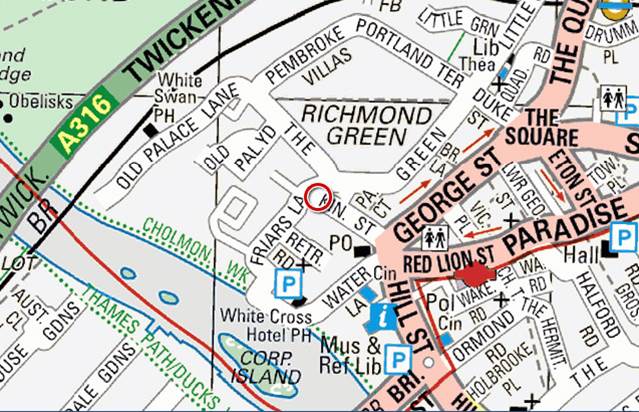

Modern map of the Richmond area with the palace highlighted in the red circle

Utilising the archive’s extensive materials and records on crown lands and property to follow the palace throughout the years allowed me to build an understanding that shows more then a simple history book version of the palace. It became not simply a building, but a hub of activity and often contentious action that helps to show the last 900 years in a very personal way.

The records held in the archive provide anecdotes and notes which humanise history in a way that cannot help but to make you laugh and connect with the past in a closer way. It is a reassuring thought that though the years may separate us we are not so different from our venerable (or not so) ancestors.

There are three things that will strike you about Richmond palace should you choose to look at its varied history – and believe me, it is well worth it to do so.

The first is the sheer amount of historically significant events to have taken place inside its walls or in its name. Richmond was – especially in the Tudor period – home to arguably the most significant events of the period. From the death of Henry VII, the founder of the Tudor Dynasty, to the palace’s eventual destruction under Oliver Cromwell, it is amazing to consider how many important events took place there.

Secondly, it is the most underappreciated, unrecognised and ignored palace in English history – a fact made all the more surprising by the first point. It is often omitted from narratives in favour of Hampton court in the Tudor period, and its roles before and after only mentioned in the most general of descriptions. Maybe this is due to the fact that the palace no longer stands or that the survival of Hampton court has superseded it, as Henry VIII’s infamy overshadowed the work of his father. Overall it must be said if one were not to look for Richmond Palace it would be very easy to never know it existed, despite all that happened there.

Lastly, and possibly explaining why it no longer stands and its unknown standing in history, Richmond Palace is without a doubt the unluckiest property you will ever have researched. Through cruel twists of fate or merely the whims of the powers that be, this building always suffered at the hands of history. This property has endured so much bad luck I am surprised that even its one remaining wall still stands. For that is all that is left of the once magnificent palace: a single forgotten wall.

Domesday to Henry VII

The first noted history of the site that was to become Richmond Palace was in the Domesday book. The manor of Shene (later spelt Sheen) was part of the royal manor of Kingston; it was owned by Otto de Grandson, a knight from savoy who worked for the English crown and Edward I. Upon Edward’s death, de Grandson left England and the manor reverted to royal hands. It was later, in the reign of Richard II, that the first major works were done on the manor. Around the mid 14th century the manor was enlarged, reinforced and embellished to make it in to a true royal residence, taking the name of Shene (Sheen) Palace and becoming separate from the lands of Kingston.

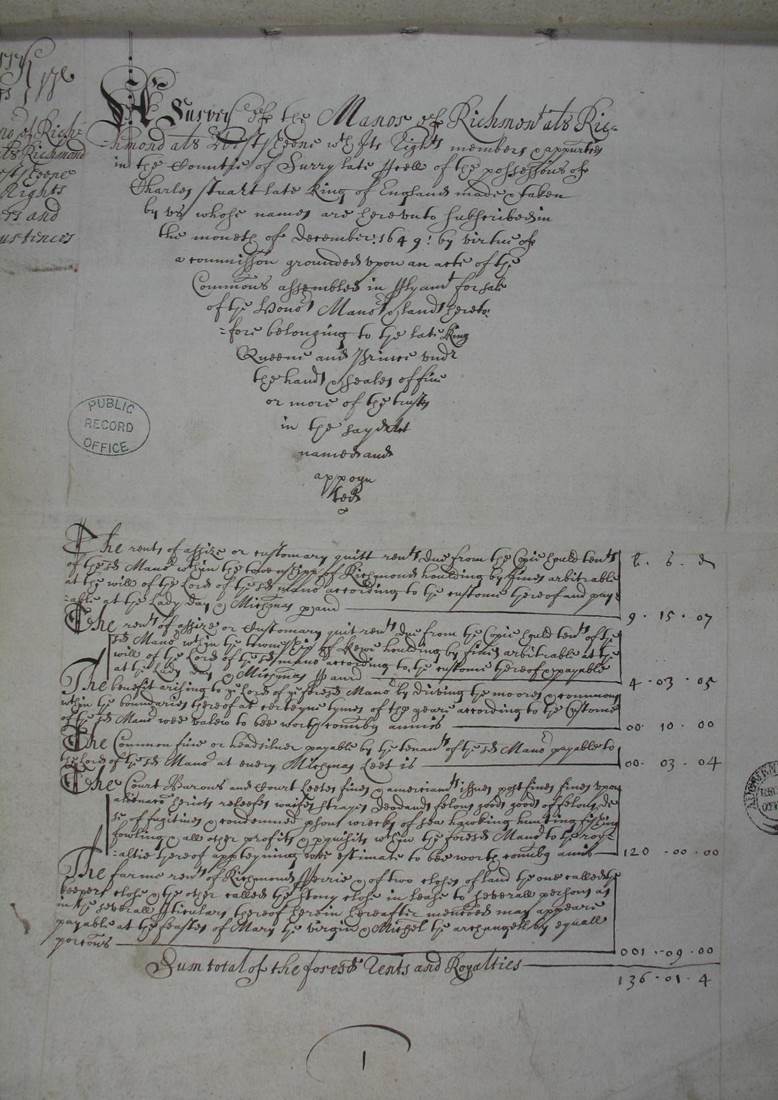

A 17th century survey of Richmond Palace (catalogue reference E 317/Surrey/46)

Richard II was the first monarch to take Richmond as his home; he and his new wife Anne of Bohemia settled there in 1383. This is when tragedy struck the palace for the first time, in what would become a series of unfortunate events leading to the its downfall: Anne died from the plague, a blow from which Richard never truly recovered. His mourning for her was so great he demanded the palace they shared be destroyed. Shene Palace was destroyed completely and its resources reused round the country (Foreign account roll, 3 Hen IV, rot H).

Its first resurrection was under Henry V, 30 years later. He decided that he wanted a palace in the area and attempted a large scale upheaval of the land. He planned for a large stone building, but due to the constant wars with France money was diverted from the palace. The palace fell into neglect, with very little work done during the remainder of Henry V’s reign and none after his death. The palace was left mostly made from wood.

New work was only undertaken in 1445 when the new Sheen palace was hurriedly repaired to house Henry VI’s wife Margaret of Anjou. After this very little work was done – only general repairs and maintaining the palace.

Five years after his ascension to the throne Edward IV gifted the palace to his wife, Queen Elizabeth Woodville, as her residence for life. She held and maintained the palace until 1487, when it was taken from her by Henry VII.

A period of splendor

We now come to a period of growth and splendor under the control of Henry Tudor. Henry went to great efforts and expense (catalogue reference: E 101/414/6, f.3) to raise a palace that would be the rival of any in Europe, a crowning achievement in his new kingdom. As the work was ongoing, however, disaster struck once more: while the court was there for Christmas in 1497, it is thought that a fire in the private chambers got out of hand. It raged for three hours and destroyed almost all the palace. Ancient tapestries were left as ashes and much more was destroyed. The damage was extensive and it was considered to have cost more than 60,000 ducats to repair.

Fortunately Henry, unlike his predecessors, was unwilling to let the ruin lie and immediately embarked on a mission to restore his palace, hiring various master craftsman (catalogue reference: E 101/414/16 ; E 101/415/3,). Around four years later, in 1501, the palace was completed and commented upon to be a true renaissance palace in England. Henry formally renamed Sheen Palace, and in his family’s honour it would now be known as the palace of Richmond (catalogue reference: E 404). Soon after the whole area would be known as Richmond.

This was an unfortunately short period of tranquility for the ever-turbulent Richmond. In the year 1506 yet another fire broke out in the king’s chamber, destroying the room but luckily not damaging the structure of the building itself (Great Chronicle, p. 330).

A second fire was bad enough, but much worse was to come. In 1507, Prince Henry had just finished walking through the galleries when for no reason they collapsed, almost killing the would-be king. Furious, Henry had the builders imprisoned and the whole palace renovated but it was just one more step in the wrong direction for the palace.

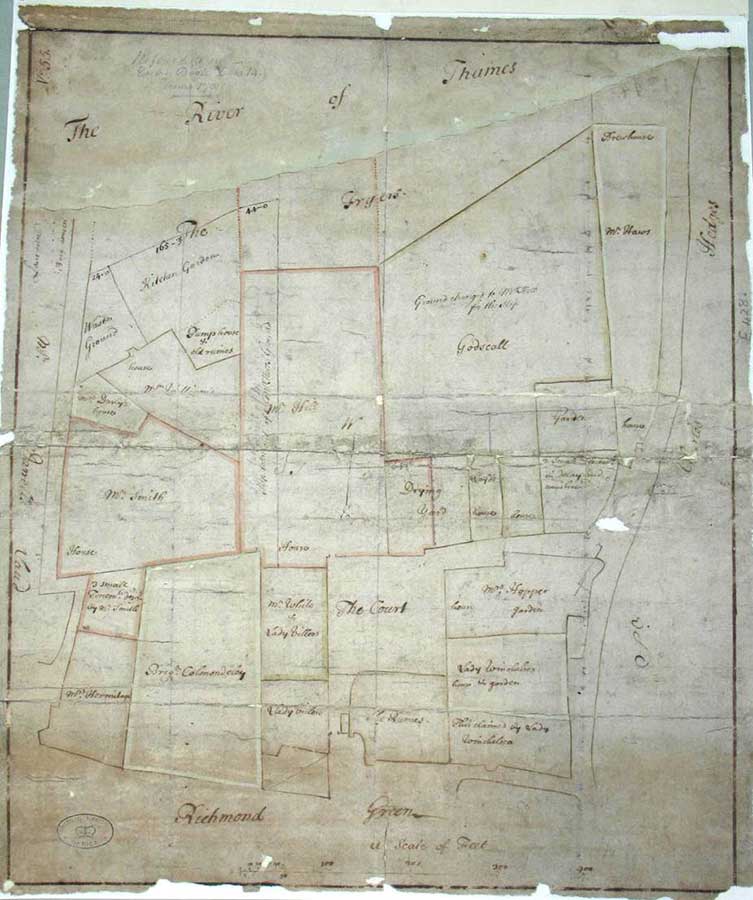

Plan of Richmond Palace, as it appeared in 1701 (catalogue reference: MPE 1/428)

Palace of the forgotten queens

The next period of its history was a convoluted one, with many residents walking its halls. It seems Henry VIII did not share his father’s love for the palace and instead took Hampton Court to be his home. He passed Richmond off to Wolsey, and once Wolsey fell from power it became the ‘Palace of forgotten queens’ where Henry would hide his past conquests in favour of his new paramours.

It is in this way that the palace came to house Catherine of Aragon and Mary, and later it was given in the divorce settlement to Anne of Cleves. While held in little regard by their father, Henry’s daughters Mary and Elizabeth both came to love Richmond Palace. Mary took her honeymoon there and Elizabeth spent much of her time at Richmond in her reign, and delighted in hunting red deer in her newly named ‘Newe Parke of Richmonde’ (now the Old Deer Park) and often had plays performed in its halls, notably many of the plays of William Shakespeare. Elizabeth, like her grandfather, died in Richmond Palace and left it to a successor who did not much care for it. James much preferred the palace at Westminster and allowed once again for Richmond to become nothing more then the house for royal children.

The end of the palace

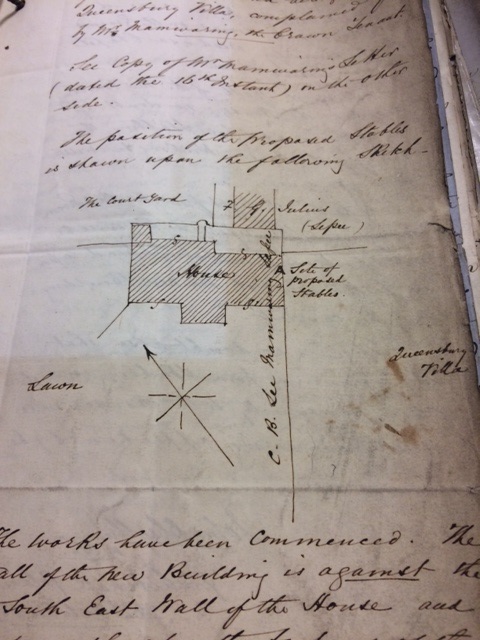

Petition against the building of a stable submitted in 1873 by Colonel Wilbraham (catalogue reference: CR35)

We come now to the greatest tragedy to fall on the most beautiful of palaces: Oliver Cromwell. After the execution of Charles I it did not take long for the commonwealth to strip the palace of everything of worth, right down to the stone from which it was built, for profit and to destroy a symbol of the monarchy they had come to hate.

This was the straw that broke the camel’s back for Richmond. A small manor house was built but the palace never recovered. What was left fell into disrepair and the ruins were never rebuilt.

As time went on and the lands fell back into the hands of the crown, no one seemed to want to waste the money on rebuilding the palace. Instead, the crown eventually started letting out the grounds to bring in revenue.

By the early 18th century the land had been split into many new houses; the largest of these were the Trumpeters house and Asgil house, which together claimed most of the front of the land facing the Thames and still survive to this day. The remaining lands have been split into various and changing houses that typically have the name of what previously lay in its place – for instance the stables, the wardrobe, the gatehouse and the maids of honour row.

While available to rent from the crown by anyone, it has always attracted people of significant background, from Colonel Wilbraham and the Earl of Cholmondeley to George Cave, who was at one point Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain (and to whom a plaque still stands).

By looking through the archive one can trace the entire history of the palace down to the men who lived there, from its humble beginnings as a knight’s manor to its time as the crowning glory of the Tudor dynasty, until its eventual fall to nothing. What more can be said but that the palace has a beautiful wealth of history and terrible penchant for the unlucky. Were it not for the still-standing Hampton Court, Richmond might be a household name in the historical community rather than an almost forgotten footnote.

If you have found anything interesting in this blog, as I did when I came to write it, I urge you to look up these files and see the wealth of stories left behind – too numerous to recount here. Failing that, all one needs to do is walk round Richmond to see the signs of the once powerful palace lost in plain sight.

Excellent piece; absolutely fascinating. A great read and, interestingly, about a part of local history that is not often covered.

Check out time team series for Richmond palace well worth a watch with excavations in various places on the site all these years later

I would like to mention the four Treasury documents in the T 1 series on fines in 1757 relating to the former site of the Palace, you will need to search under “Palace of Richmond”, other files are also listed under “Richmond Palace”. As far as Cromwell goes this is my view no different from Henry VIII destroying the monasteries for a similar reason.

Would you have any thoughts on where I may find any records concerning the stained glass that might have been at Richmond Palace? I know from the internet that a me flowers wascomissioned to make some but can find nothing else

I have looked in the local study section if Richmond library but again no luck

There was a nice flow of tragedy in this blog on the “Lost Palace.” Charles 1 was a key resident in the Palace and his death by treason would be an interesting aspect to explore in more depth. This was a key time for the Palace and its fate may have all come down to the “unlucky” turn of events which left the King executed as he was held to account by Parliament.

I would also love more details about the treasures the Palace held and especially, where the artwork which survived the fires, is now located?

Thank you, and well done for a very interesting piece.

The history of Richmond Palace is indeed quite incredible, and as such has been researched quite extensively before – none more so than by the late, great, local historian, John Cloake in his two volume book, ‘Palaces and Parks of Richmond and Kew’.

As a very keen amateur Richmond local historian myself, I hope you will not mind if I offer just a minor piece of critique:-

I am NOT an expert on the Palace by any means – however – you are correct in saying Shene was renamed as Richmond – but I’m not quite sure it is correct to show the same connection between Shene and today’s Sheen?!

(As an aside, my former school was ‘Shene Grammar’ in East Sheen – the name of which reflects the time when the Richmond County School for boys was combined with the Sheen County School).

Also, if I have understood your blog correctly, it appears you are saying all the surviving ‘old’ buildings are from a later c.18th Century period?? I reiterate, I am not an expert on Richmond Palace, but it was/is my belief that some parts, including the Gate House and the Wardrobe, were surviving parts of Henry VII’s original early16th Century Tudor Palace?!

As I said though, thanks and well done for an interesting article.

I thought I’d have to read a book for a disovcery like this!

Well done Marcus! A very interesting history of somewhere forgotten with time!

Thank you for the very interesting post, I always thought that Sheen and Richmond were 2 different Palaces. ?? I do have a question ? Can I get the book the John Cloake wrote about ” Palaces and Parks in Richmond and Kew, in the States????!, and are the files on the Lost Palace available on line??! Any info greatly appreated.

Hi Lynn,

Thanks for your comment.

We’re unable to help with research requests on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

I hope that helps.

Nell

I am interested in understanding why Henry VII took the palace from Elizabeth Woodville, who, if my limited knowledge of 15th century England is correct, was his mother-in-law.

Thank you so much for your research. As an American keen on English history, I love blogs such as this.

i have always thought 2 of the most important an fascinating Tudor palaces, Greenwich and Richmond, were gone to history and wondered why no one cared. Thank you for reviving interest.

Thank you for your wonderfully researched account of this sad place. sad, because so often it seemed to make a great effort to rise again, only to drop into disrepair and despair. I lived in The Wardrobe from 1965 – 68 (I think), and were told that Elizabeth died in the gatehouse while a messenger waited under the arch to take the news to James. (not a likely story)!It was a much loved building by me and my two young children who loved nothing more than running up the stairs, then round through the upstairs rooms and out again, and down under what we thought was the Minstrels Gallery.

Once inside the Georgian front door is the Tudor front – the only remnant of the Tudor building but even more magical for that! I would love to know what the original purpose of “The Wardrobe” could have been.

The Wardrobe in Old Palace Yard was used for Royal clothing and trunks of Queen Elizabeths dresses were found there and they were many. My Husbands great great grandfather Churchill Julius was born there, his father Dr Frederick Julius resided there with his siblings and his father Dr George Julius resided there from the early 1800s. The Julius family resided there for a large period of the 1800s. The Wardrobe at this time was one complete dwelling not divided into appartments.

In a poem “Sollitudo regia Richmondiensis” contained in a volume of poetry published in the early eighteenth century Vincent Bourne writes of Richmond as a place the king sometimes retired to get away from the hustle and bustle of the Court. In the absence of Richmond Palace, where would he have resided in Richmond?

Thank you. That was wonderful to read and has spurred me into researching more about what was left of these buildings.

Thanks

I am part of this bloodline and would like to know how to claim or get in contact with some of my relatives over in richmond England. I would love to bring the castle back

Hi Marcus, a gear narrative. I’d love to re-visit your sources at the National Archive, are they listed anywhere?

Interesting article, thank you.

You say just a wall remains of the Tudor Palace. Aren’t the gatehouse and the Wardrobe part of the original 1501 palace?

Great article, thanks. I was told that Chaucer was employed by the palace and also that much of the England-Scotland formal negotiations were held there. Any truth in these?

Great piece. Absolutely fascinating!