In 1990, a march in protest of the government’s Poll Tax turned violent as police and those marching clashed. The Poll Tax Riots became one of the most infamous protests in recent British history but this wasn’t the first time protesters rioted and set fires in London to show their anger at a poll tax. In fact, 600 years earlier, the first mass uprising in English history was prompted by a very similar situation.

With the help of archives, historians, and records experts it is possible to uncover the real story behind what we think we know. This is what The National Archives is aiming to do with the second series of our podcast, On the Record at The National Archives, which is looking at the topic of protest. In episode one we use the medieval records in our collection to uncover the real story of the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381.

To coincide with the release of episode one I asked Euan Roger, one of our Medieval Records Specialists, a few more questions that we couldn’t fit into the episode.

[Katie]: The Peasants’ Revolt was against a fixed-head, or poll, tax that ordinary people were required to pay. Could you explain a little more about that and was this the only tax that households were paying to the Crown?

[Euan]: Taxes on individuals during the medieval periods were levied to provide income for specific items of expenditure, such as military campaigns, with each tax levied separately. Taxes were generally granted by Parliament, but could also be be imposed directly by the monarch, such as feudal and prerogative levies.

The poll taxes were levied on individuals rather than property or wealth, with everyone over a certain age, and not otherwise exempt, being liable to pay a given amount. In the tax agreed in December 1380, all individuals of both sexes over the age of 15 were to pay 12d (or 3 groats) each, although beggars were exempted, and communities were supposed to assist each other in paying.[ref]12d was the average sum, although the more affluent of each village were to assist the less well-off, provided that no one had to pay more than 60 groats for himself and his wife, nor was allowed to pay less than 1 groat (4d) for himself and his wife. Further details about the tax and its collection is available in our E 179 database, and in our research guide to Taxation before 1689.[/ref]

The commons estimated that this tax would raise 100,000 marks for the king, but made its grant conditional upon the contribution from the clergy of an additional 50,000 marks. They also insisted that the money be used for the maintenance of the Duke of Buckingham’s army, although by the time of the second attempt to collect the tax in June 1381 (the attempt which would spark the revolt) Buckingham’s planned invasion of France had been abandoned.

[Katie]: How informed was the argument of those involved in the uprising against the poll tax?

[Euan]: In the years leading up to the main revolt, we find petitions being presented to the King and parliament from several major landowners around the country, which shed light on some of the innovative ways that tenants were fighting for their rights.

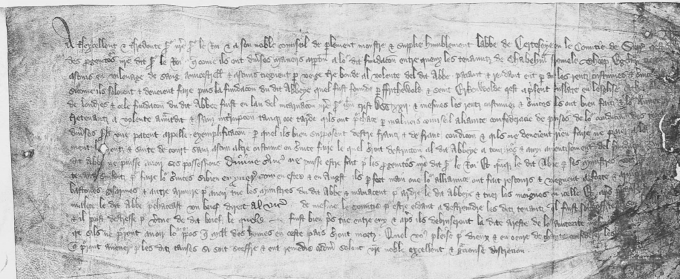

Tenants in Surrey resisted paying taxes and threatened to burn Chertsey Abbey and to kill the monks in protest, 1378. Catalogue ref: SC 8/103/5106

Tenants around the country – including those who worked the lands of Chertsey Abbey in Surrey – banded together to resist their landlords, and refused their customary services and rents. But as well as threatening violence, some tenants used historical precedent to try and force the issue, and produced exemplifications (official copies) of the Domesday survey, which they argued contained no mention of such conditions. The parliament of October 1377 would judge such actions to be rebellious, but such actions were an innovative and considered move on the part of the tenants.

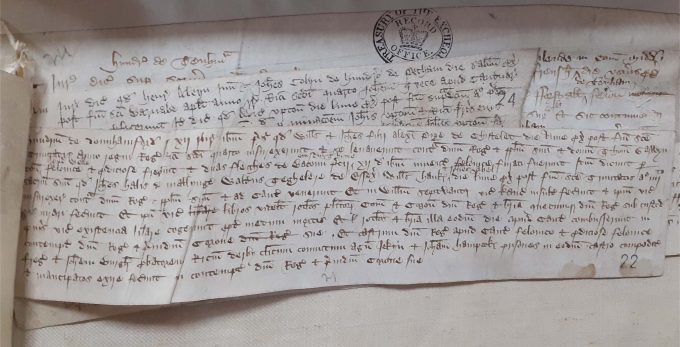

Inquiry into the Peasants’ Revolt 1381, file of indictments. Catalogue ref: JUST 1/400

[Katie]: In the podcast you describe some of the violence used as a method of revolt by the rebels. However, what other methods were used?

[Euan]: One of the main issues that we hear about from landholders is the destruction of official documents in the uprisings, particularly court rolls, the records of the local manors. For wealthy landowners such as Chertsey, the official documents in their archival collections were proof of the grants, liberties and endowments they had been granted historically, but the abbey’s cartulary records several court rolls and muniments were destroyed in the 1381 uprising. For many in the uprising, such documents would have represented the ‘official record’ of their subjugation, and by burning these collections they could destroy the proof of such a status.

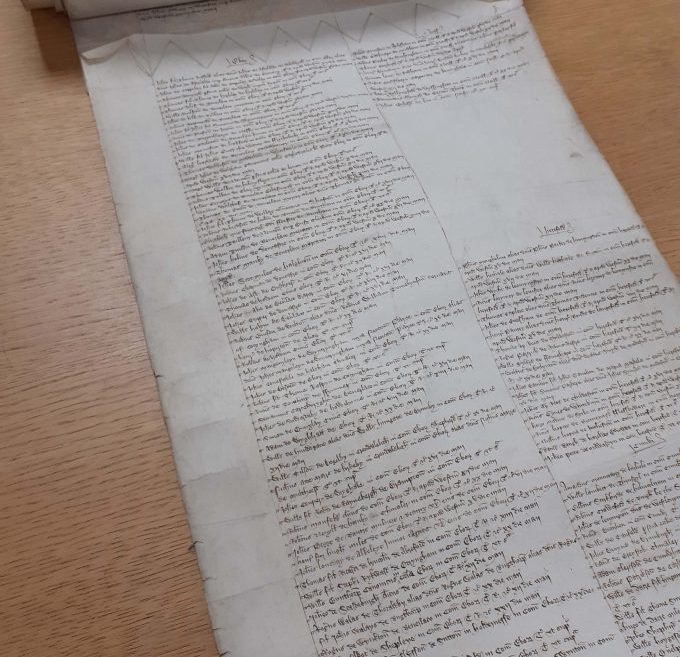

Pardon roll for those given an amnesty after the peasants’ revolt. Catalogue ref: C 67/29

On the Record at The National Archives: series two

Episode one is now available on the Archives Media Player and on podcast listening apps. The second instalment will be available from 23 January and will focus on the fight for suffrage and how the suffragettes turned to militant tactics to get their message across.

You can also catch up on series one which focused on espionage using personnel files, secret government reports, and declassified correspondence to uncover the true stories of famous spies.

Subscribe: iTunes | Spotify | RadioPublic | Google Podcasts