Content note: This blog includes references to domestic abuse.

2024 marks the 50th anniversary of the foundation of Women’s Aid. The grassroots federation of charities was created following the pioneering work of Chiswick Women’s Aid in the 1970s, which became the charity Refuge in 1993.

To mark this I’ve written a story exploring the first few years of the Chiswick Women’s Aid, and how it became the first shelter for women fleeing domestic violence.

In this post, I will talk you through my research into this story, the difficulties I experienced accessing records, which register traumatic experiences, and how this led to a moving personal encounter.

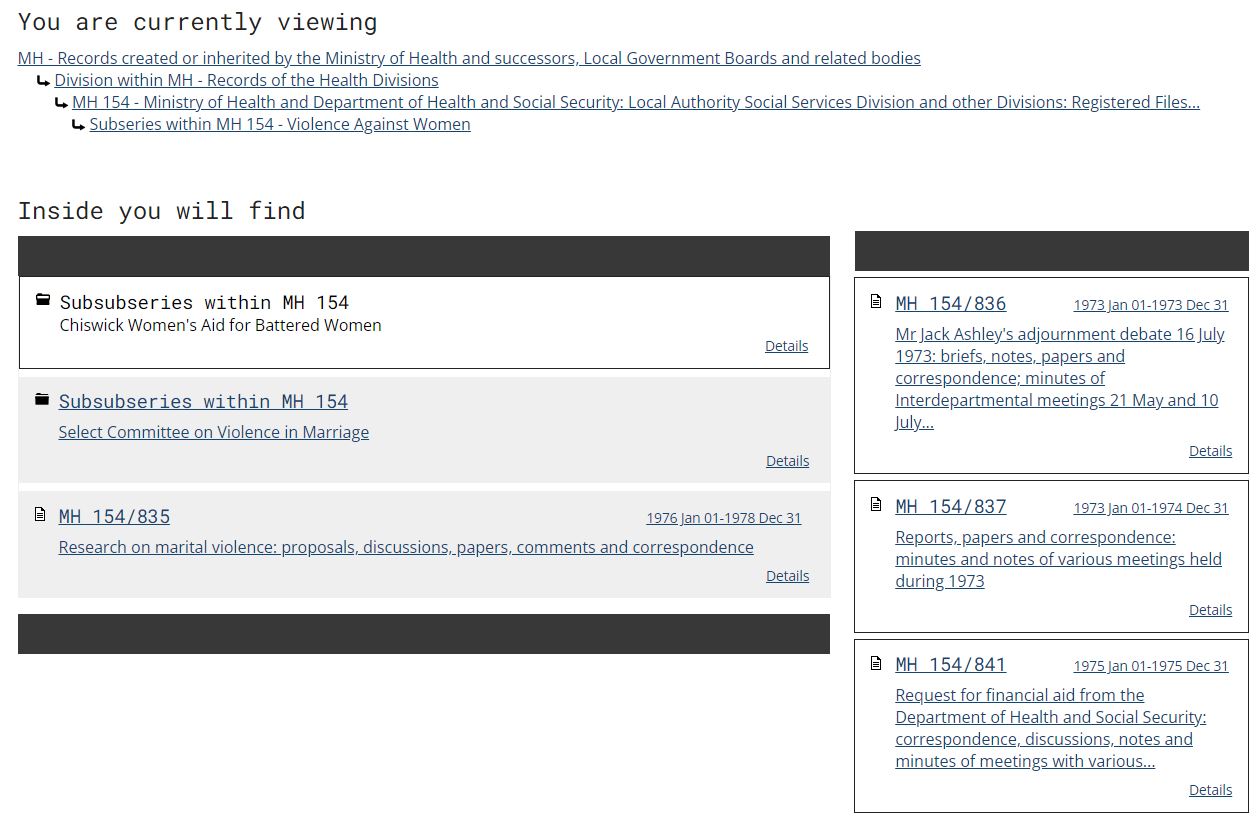

The National Archive records

I had read about the Chiswick Women’s Aid refuge while researching the history of squatting in the 1970s. It wasn’t immediately clear to me if this experience was to be considered a story of squatting and I had promised myself to dig more into it, but what caught my attention was that it seemed to be the first formally recognised refuge for women victims of domestic violence in the world. The story was quite extraordinary, so I started following its thread back in time.

The first obvious place, as a Collections Researcher at The National Archives, was to search our records. The National Archives holds records relating to activities that have in some way interacted with the state, so I didn’t expect to find any ephemera related to the experience.

As predicted, the catalogue suggested a number of records within MH 154 – Violence Against Women. These are broadly divided into correspondence between the Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS) and Chiswick Women’s Aid (CWA), correspondence around the Select Committee on Violence in Marriage, and research on marital violence reported to DHSS, which would eventually inform the 1976 Domestic Violence and Matrimonial Proceedings Act.

Accessing documents recording traumatic experiences

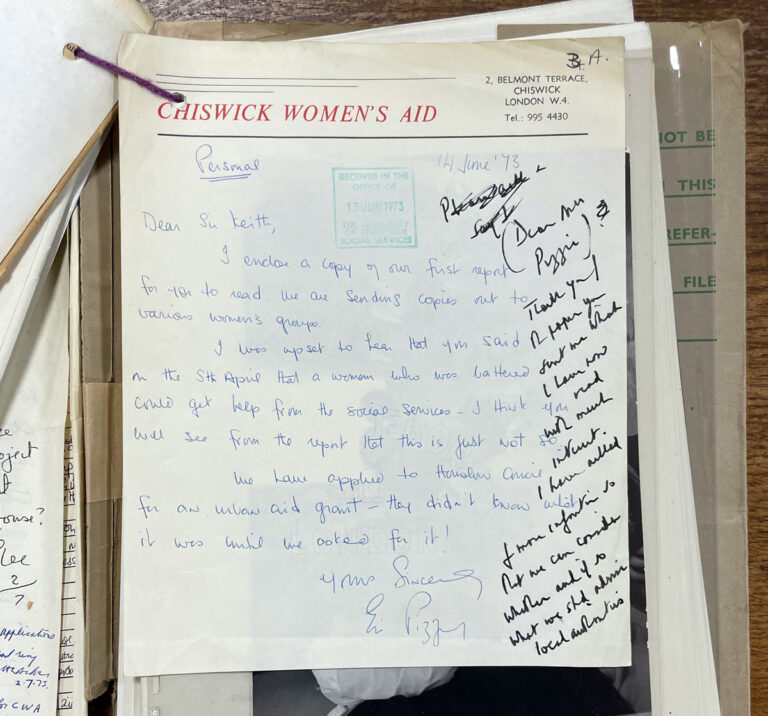

The most interesting among the MH 154 subseries was MH 154/837. This included all the initial correspondence between Chiswick Women’s Aid and the Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS). According to these documents, although the centre was run collectively by the women who lived there, it was severely under-resourced so requests for funding were regularly submitted to the DHSS and Hounslow Council.

One letter is of particular importance because, to give evidence of the gravity of the problem it includes a report that CWA commissioned from the Inter-Advisory Service which describes the social problem of ‘battered women’ (the term was the accepted terminology at the time, used by women themselves; ‘domestic violence’ was only first used in 1973 and adopted at a later stage) and details what services the centre was providing to help them.

The report’s aim was to provide a snapshot of what was being done to protect women seeking shelter, and reading it was a vicarious experience of trauma. Not only the problematic language, and assumptions made about the causes of domestic violence, especially in the light of our contemporary understanding of it, but the list of case studies provided to support evidence can be traumatic to read.

As a researcher and a woman, the first question I found myself asking was how to position myself in front of that long list of examples of violence. Did I have to maintain an objective distance and take the report for what it was – an ethnographic document compiled to produce some vital legal and social changes – or could I let my affective response take over?

Researching the birth of domestic violence refuges had prepared me to face retellings of violence to some extent, but I didn’t expect to have to confront so many anonymised detailed accounts of traumas. I suppose it was the list of initials followed by the details of the ‘battering’, as if these women were just a sequence of examples rather than people with feelings, that I found particularly harrowing. Their suffering body and psyche had been replaced by an initial and short paragraph. What should I do?

It was at this point, that I decided to focus on my discomfort and find a way to bring feelings and affect into the research process as a way of inhabiting this space more comfortably. As scholars worldwide are demonstrating and debating, by centring people rather than records, organisations can engage in trauma-informed archival practice that can bring liberatory memory work. I was determined to do so.

A chance encounter

As I was reading the contents of MH154/837 I stumbled upon a photograph with no caption or date, depicting some children at the Chiswick Women’s Aid refuge. It is undeniable that as I came across it, I was overwhelmed with further emotions. After all those dehumanising reports of violence, here I could finally ‘feel’ and ‘see’ what the refuge looked like.

Although traumatic experiences were looming beyond the picture, finally there was a trace of human feelings. Who had included the picture in the record? Had it been sent with the ‘Chiswick Women’s Aid and the problem of battered women’ record?

There was no way of knowing. There was no date, no photographer’s name. Nothing that could help me find out more. To protect the unknown identities of those photographed, without their consent, we’ve not included the photo.

A second chance encounter

A few days after this moving finding I happen to visit the Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970 – 1990 exhibition at the Tate Britain.

The exhibition documents two decades of radical protest work lead by women, from the first women’s liberation conference in the UK, to women’s response to Section 28, the visibility of lesbian communities, and the AIDS epidemic. Although I didn’t know when I stepped into the exhibition, it included the creation of Women’s Aid and the domestic violence refuges movement.

When I saw the pictures, I immediately reconnected them to the unnamed picture in the The National Archives’ record. I took note of the photographer and decided to chance my luck.

A third chance encounter

Christine Voge, the photographer whose pictures I had seen at the Tate, welcomed me on a January afternoon. She hadn’t taken the picture I found at the The National Archives, but, as she told me, she visited CWA on three occasions in 1978, the last one of these being two-weeks documenting life at the refuge. She was disappointed by the photographs she had taken on the previous occasions and wanted to be able to capture the essence of that time, the humanness of people living there, the joys and pains, the moments of solitude and quiet.

While she showed me the photographs taken on these occasions – photographs that hadn’t been exhibited – she told me the private stories of all the people depicted. She remembered each one of them: the lady who was very shy and spent the time separated from the group with her kids, the silence early in the morning before everyone woke up, the young American man who joined the refuge to help running it and who became a civil rights lawyer when he got back to the United States.

Before I left, she showed me one last picture. A group photo that the women living and volunteering at CWA wanted to take with her on her last day at the refuge. In this picture, Christine appears in the bottom right corner.

As I saw this photo I realised what trauma-informed archival practice practically means. It means crossing that bridge that separate us – the researchers – from the documents we research, it means to centre the research around the people, to bring them to the centre of our process and, wherever possible, to join or help them producing ethical memory work. Although I wasn’t able to ‘listen’ to the voices of the women whom I encountered in the records at the National Archives, thanks to the oral testimony and visual documentation of Christine Voge I was able to get closer to them and have a glimpse at their lives beyond the violent experiences they had been reduced to in the archive.

Find out how to get help if you or someone you know is a victim of domestic abuse on gov.uk.