If you’ve watched the TV series Welcome to Wrexham you will know that it follows the fortunes of Wrexham AFC and the local community. If you made it past the disappointment of the football club failing to get promoted at the end of the first series, you might recall an episode in series two about a mining disaster at the nearby Gresford Colliery.

The disaster occurred in 1934 when an explosion underground led to the deaths of over 260 men and boys. The Welcome to Wrexham episode showed the memorial to the disaster that was finally established in 1982, using an original winding wheel from the colliery.

Working as a visual collections specialist at The National Archives, I often watch, read, or hear about historical events or figures and wonder if they’re covered in the archive. As I watched the episode, I thought ‘I bet we’ve got something about that at work’. Usually I do a search of the catalogue just to satisfy my curiosity, but this time when I saw how much material we had, I wanted to find out more.

Searching for ‘Gresford colliery’

A search for ‘Gresford colliery’ in our catalogue brings back 137 results. Refining those results to focus on records from 1934–1938 brings the number down to 70, most of which are from the Ministry of Power (44) along with some photographs from what became the National Coal Board.

The records from the Ministry of Power include numerous files from the official inquiry into the disaster, which opened on 25 October 1934, along with files of correspondence with the community and the local newspaper, the Leader. I requested a selection of files that I thought might be interesting, but because much of this material is stored off-site it took about a week before I was able to start looking through it.

Uncovering the records

Settling down in the staff reading room with my order of files I was unprepared to feel so drawn in to the events of 22 September 1934.

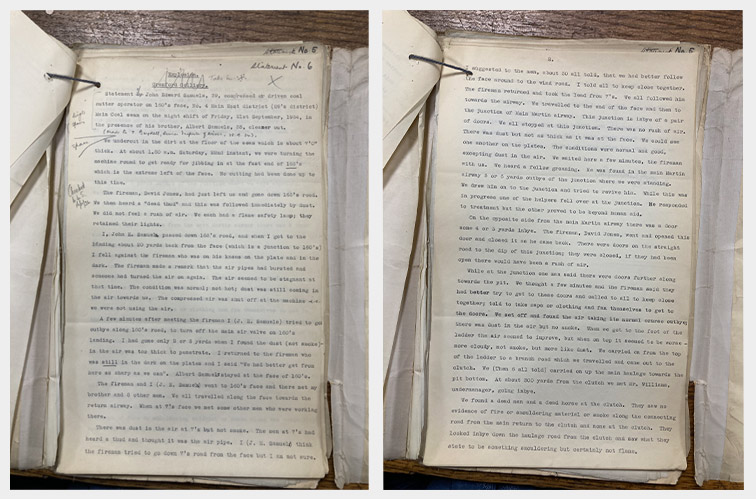

I read the account of John Samuels, one of only six men to escape from the mine that day. I wondered how he had fought the inevitable fear and panic and found a way to take assertive action and lead his colleagues to safety.

I slowly turned the five pages of close-typed text that listed the names, ages, jobs and addresses of those that had died, and thought about their families that had waved them off to work not knowing it would be for the last time.

I looked at the photographs taken by a team entering the mine in March 1935, six months after the explosion, and was shocked to see the images of twisted metal, fallen timbers and flooded tunnels.

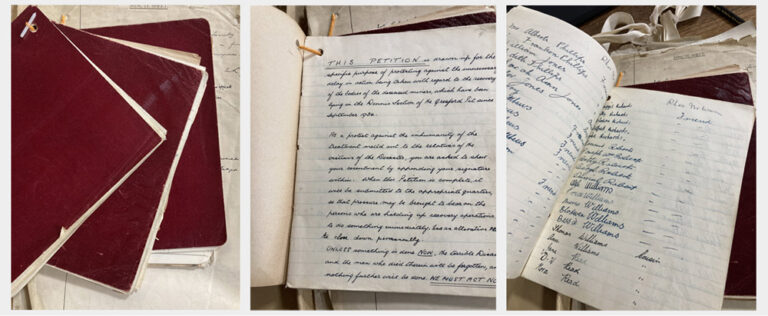

Then I opened a file entitled ‘Correspondence and petitions regarding the recovery of bodies’. Right at the top of the file of papers were three red-covered school exercise books.

Opening the top one I saw the first page explaining that:

‘THIS PETITION is drawn up for the specific purpose of protesting against all the unnecessary delay in action being taken with regard to the recovery of the bodies of the deceased miners which have been lying in the Dennis section of the Gresford Pit since September 1934.’

On the next page was the start of a list of over 2,000 names with each person recording their relationship to someone that had died in the disaster and whose body was still trapped in the mine. Mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, daughters, sons, uncles, aunts, cousins, grandparents and friends – all represented.

There was something so personal and immediate about the books. I felt as though by touching them I was connected to the people that had signed them, but even more to the person that had been out to buy the books, and then travelled (probably walked) around all the affected communities, knocking on doors and asking their bereaved neighbours to add their signature. You could feel the pain and desperation as if it was soaked into the pages.

The Cappers

I worked my way through the rest of the file and realised it contained nine letters from members of one family – the Cappers – and that they had also raised the petition contained in the three exercise books. Emily and William were the parents of John Capper, a 35-year-old miner killed in the disaster, and Margaret and Edith were his sisters.

In other files, I found reports that Emily had visited the colliery offices every week for two and a half years asking for the body of her son and his colleagues to be recovered, and I was drawn even further into wanting to know more about her.

The present day

I wanted to write something for our website about the disaster in time to mark the 90th anniversary on 22 September 2024, but I wanted to be sure I respected the feelings of the local community and those that had family members involved in those tragic events. I found a Facebook group for relatives of people that had been killed and contacted the group’s moderator, Margaret Jones.

Margaret and her husband Alan were also on the committee of the Friends of Gresford Colliery Disaster Memorial and were interested in knowing more about the documents held in our collections at Kew. They came down to London in April and we looked at some of the records together. They had seen an awful lot of documents from other sources, but most of what I was able to show was new to them.

Margaret and Alan were able to check with direct descendants of people killed in the disaster, as well as a relative of the Capper family, and explained that keeping the memory of the disaster alive was important to the community. They were keen to support anything that would help to do this and so were happy for me to go ahead with my plans to write something for the website. With the essential advice and support of Margaret and Alan, I drafted the article which was published a few days before the anniversary of the disaster.

Through my research I became emotionally invested in the story of the disaster and decided to make the journey to attend the various events that the community organised to mark the anniversary over the weekend of 21–22 September.

Going to Wrexham

Saturday saw a minute’s silence and the laying of a wreath at the Wrexham AFC match against Crawley Town F.C. In the evening, Wrexham Miners Project volunteers lit 266 candles at the Mines Rescue Station in memory of each of the miners who began their night shift on the Dennis section of Gresford Colliery in 1934. Family members were invited to light the candles, and Ruby McBurney, the 93-year-old daughter of William Crump, lit the first. The candles were extinguished just after 2am on Sunday, the approximate time and date of the explosion.

On Sunday morning the Friends of the Gresford Colliery Disaster Memorial held a service at the memorial wheel. School children, the Mayor, and representatives of Wrexham football club were among the crowd of around 250. Wreaths and flowers were laid as people sheltered from the light Welsh drizzle under their umbrellas and coat hoods. The service was accompanied by the Llay Welfare Brass Band which played ‘Gresford’ The Miners’ Hymn, sung to the tune of Abide With Me, and the English and Welsh National Anthems.

Later that afternoon a service was held in All Saints’ Church in Gresford, again accompanied by the Llay Welfare Brass Band. The congregation was invited to light candles in memory of the men and boys that had been lost, and to view the mural by Denise Bates in the Trevor chapel, which was painted in 1994 to commemorate the mining disaster.

People travelled from all over the UK to pay their respects at the different events. Some people met for the first time and realised they had a shared ancestor that died in the disaster. The strength of connection to the events of the past was palpable, and the commemorations showed the importance of a shared history that can still draw a community together, even after 90 years.

Read Sarah’s story of the 1934 Gresford Colliery disaster and Emily Capper’s campaign for justice

Thank you Sarah. Fascinating! I too love the details – to imagine them living their lives, and the catastrophy of the loss. I thought to write a full feature film on a mining accident, showing the poor standards and the rich owners not caring so much, enjoying their wealth. Very socialist. Would you like to be my researcher? Best wishes John.

I first heard of “The Gresford Disaster in Ardmore, Co.Waterford, Ireland in 1965 when the late lamented Dave Burns, one of a holidaying Welsh Folk Group, “The Hennessys”, sang it in our local bar. It struck a sympathetic chord with all present and several of our local singers added it to their repertoire for years afterwards. Dave’s soulful rendition added so much to the tragic ballad. The other members of that group, to the best of my memory, were Paul Powell and Frank Hennessy of BBC Wales Radio fame.

When we moved to North Wales, just outside Wrexham, in 1970 the Gresford disaster was still very much talked about. Having moved from a mining area in the Midlands, in fact my father, from the age of 14, spent his whole working life in colliery offices, I was well acquainted with miners’ lives. We also had a Mines Rescue Station in our town and as a child I was lucky enough to be shown round. It made a lasting impression on me that I’ve never forgotten. It was “good” to read about the disaster. I well remember hearing about the erection of the memorial although by that time we had left North Wales, the winding wheel a very fitting memorial.

My Auntie is Ruby McBurney, daughter of one of the miners (William Crump, also my grandfather) who you mentioned above. She campaigned for many years to have the names of the miners added to the memorial. How very sad that it took so very long to add the names when they had no graves or headstones. This should have been addressed by the authorities back in 1934/35, shame on them.

So many deaths and memories across the old coalfields. There always seems to have been a big fight to get memorials as its hard to acknowledge the very real cost of our perceived progress. It took years for the Senghenydd memorial to be erected in South Wales, 1981.

Then eventually the village’s garden of remembrance was officially opened on the 100th anniversary of the 1913 disaster when 439 miners were killed after an explosion tore through the Universal Colliery, the very worst disaster in the history of British mining, which commemorates those who died and was formally acknowledged by the Welsh Government as the National Mining Disaster Memorial Garden of Wales.

I have recently found out more information regarding an uncle who died.

My mother who was in Ill health (deceased) always used to talk about her brother but we assumed her memory was not what it should have been as names didn’t match.To surprise we find he didn’t have same surname & nor could we find a John Davey…. I now find his name was John David(Davey) Rowland & he was 17 years of age..I have found various things out but I really would love a decent picture or image of him.Image at the Wrexham Miners Rescue found but it’s not the best…Would love some help in getting one please