The release of the 1921 Census has allowed people to uncover some fascinating stories, solve family mysteries and finally break down the occasional genealogical brick wall. We’ve really enjoyed hearing accounts of what people have found about people and places known to them.

While the 1921 Census did have a very detailed schedule, and provided a lot of new information about people, particularly with regards to their employment, it does not always provide the information people might hope for.

It was not until the 1991 Census that ethnicity was recorded on the Census in England and Wales, and as a result it can be difficult to trace diverse communities. In order to trace communities of Black heritage, for example, we are entirely reliant on finding them through places of birth, which in turn can be problematic. Firstly, it overlooks people from Black communities who are born and raised in the UK, relying on subjective assumptions such as type of employment or name – neither of which is actually that useful in tracing people. And secondly, it only enables the identification of first generation members of that community, and relies on place of birth as the identifying factor. Again, this is not without its problems.

Here are a few tips for researching Black history in the Census, which may help you find what you’re looking for.

If someone lists somewhere in the Caribbean or in Africa as their place of birth, then they might have Black heritage. However, given the extent of the British Empire at this point in time, place of birth alone is not evidence enough. We know that there were sizable populations of white people across Africa and the Caribbean, as well as extant Black communities in the UK going back many generations, so details of a place of birth are inconclusive. Evidence of ethnicity in this source is rarely explicit, and using this evidence alone, answers are rarely definite. However, it can be possible to trace people of Black heritage in the Census, using other sources to corroborate your findings.

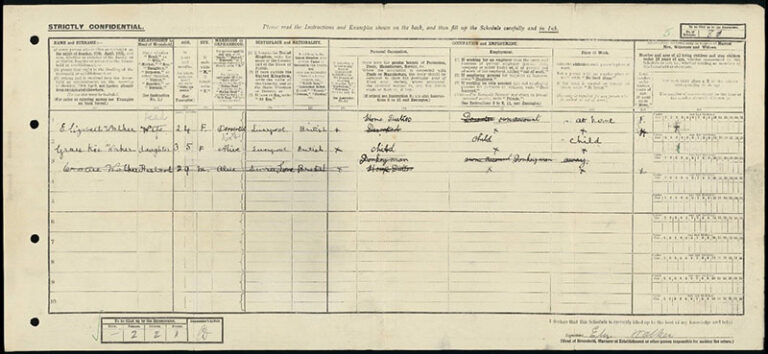

One example of this is a man named Cratue Walker, who appears in a roundabout way in the 1921 Census. The census return was filled in by his wife, Elizabeth who was living with their three-year-old daughter in one room in Liverpool, and she has included Cratue on the schedule. It looks as though Cratue was not at home on the night of the Census, and the enumerator subsequently crossed out his entry. As his entry was crossed out, he would not have been included in the official statistics. But because the original household returns survive, we can still see his entry.

A broader search reveals that this merchant seaman was almost certainly in Louisiana on the night the Census was taken, having travelled there aboard a merchant ship as crew earlier in the year. Electoral registers for Liverpool also suggest the Walkers moved around a fair bit, between lodgings, so tracing their residence is not always easy. This entry reveals Elizabeth and Grace were living in a single room on the night the Census was taken.

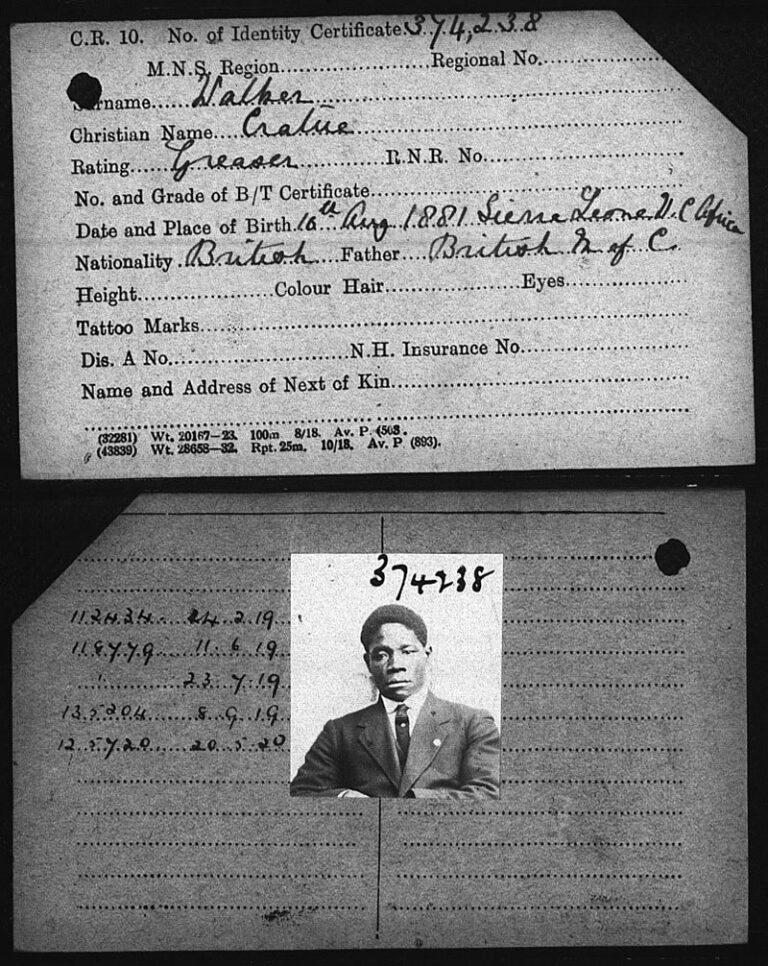

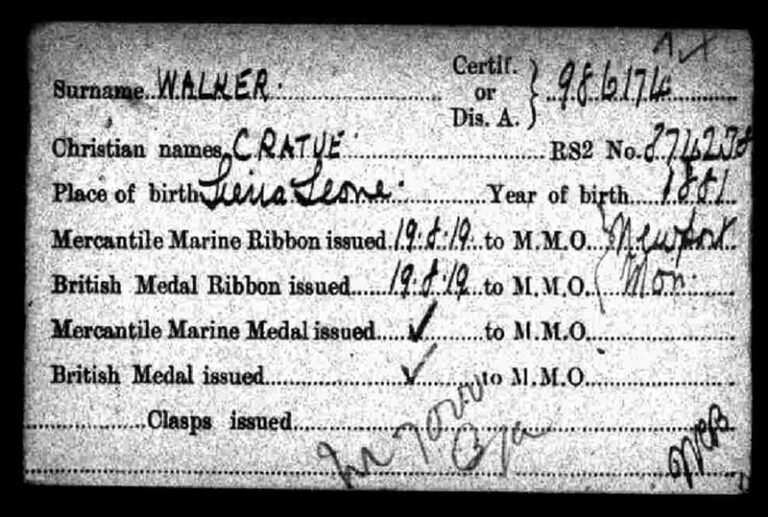

Cratue’s place of birth is listed as Sierra Leone, and you can search the 1921 Census by place of birth. This is how I came across him. Subsequent searches revealed his entry in the Merchant Navy Register of Seamen (1918-1921, BT 350) – this is one of the few contemporary sources which also has photographs, and it was brilliant to be able to put a face to a name.

Details of his service during the First World War, and his associated medals, are also listed in Discovery.

When searching for people in the Census, you might also draw conclusions based on people’s names, though bear in mind that names may have been written down incorrectly by someone else when a census form was filled in, or when the details were transferred to the enumerator’s copy (in earlier censuses). Different naming traditions may provide key links to an individual’s heritage, and these may be present in the Census. However, this is not always possible.

If you are interested in searching for people who list a particular place as their place of birth in the 1921 Census, then the following tips may help:

- Familiarise yourself with the names that countries or cities were called in and before 1921, as they may have changed since then.

- Search for countries rather than cities, as these are not always listed where people were born abroad.

- Use wildcards to aid your searching: Bris* will bring up Bristol, Brisley, and Brislington, among others, for example.

You can only find places of birth in the 1921 Census for ‘England and Wales’ if they are transcribed correctly, many aren’t!. Of course we are awaiting the 1921 Census for Scotland (due this year) to have a complete picture.

Really interesting article. Thank you. Such a pity it’s still behind a paywall for us in the north (our local library service can’t afford to subscribe) so will have to put off our own search for Black ancestors for a bit longer. Great info here though.

Cratue Walker’s mixed race Liverpudlian daughter Grace Wilkie is mentioned in my book Under Fire – Black Britain in Wartime 1939-45 (The History Press, 2020). I remember seeing her on BBC TV in the 1990s in a series called Black Britain.

Thanks very much for alerting me to this. I’ll be sure to get hold of a copy. All the best, Jessamy