Below, Principal Records Specialist (Medieval) Paul Dryburgh discusses his research conducted as part of the The Northern Way project, an AHRC-funded project being conducted in collaboration with the University of York and York Minster.

This is the second blog in our Research Exchange series, which features interviews with researchers across The National Archives, where they discuss their new discoveries and their work’s potential for impact. The purpose of the series is to highlight and demystify the research we do and open up new ideas and discussion.

Read the first Research Exchange blog with Jonathan Mackman here.

Could you give an introduction to your research focus for this project and the ways in which it demonstrates new methodologies and research questions?

As Co-Investigator of The Northern Way, my principal focus, with research associate Jonathan Mackman, is to explore records in the archive of medieval English royal government that are relevant to the history of the northern Church and to the roles of northern clergymen in national administration.

In a century of significant expansion of bureaucracy, and therefore of record-keeping, one of the main questions we want to explore is the extent to which, as earlier generations of historians have suggested, clerks of northern birth were introduced into the main organs of state, the Chancery (writing office) and Exchequer (finance office).

We want to see whether we can discern any particularly or peculiarly ‘northern agenda’ in administration and in royal policy on the back of this. The 14th century, after all, saw the north of England repeatedly under pressure from Scottish raids, famine, both human and animal, and epidemics. It also saw the eight archbishops of York from 1304 to 1405 occupying senior administrative office and often enjoying strong personal relationships with kings. The influence of these men on their own church and on government is central to our research.

What is the most surprising or interesting thing you have discovered?

I’m bound to say that everything we’re finding is of great interest, aren’t I? Surprising, perhaps less so. Personally, I am most interested in King Edward II (1307-27) and some of the leading figures in his turbulent reign.

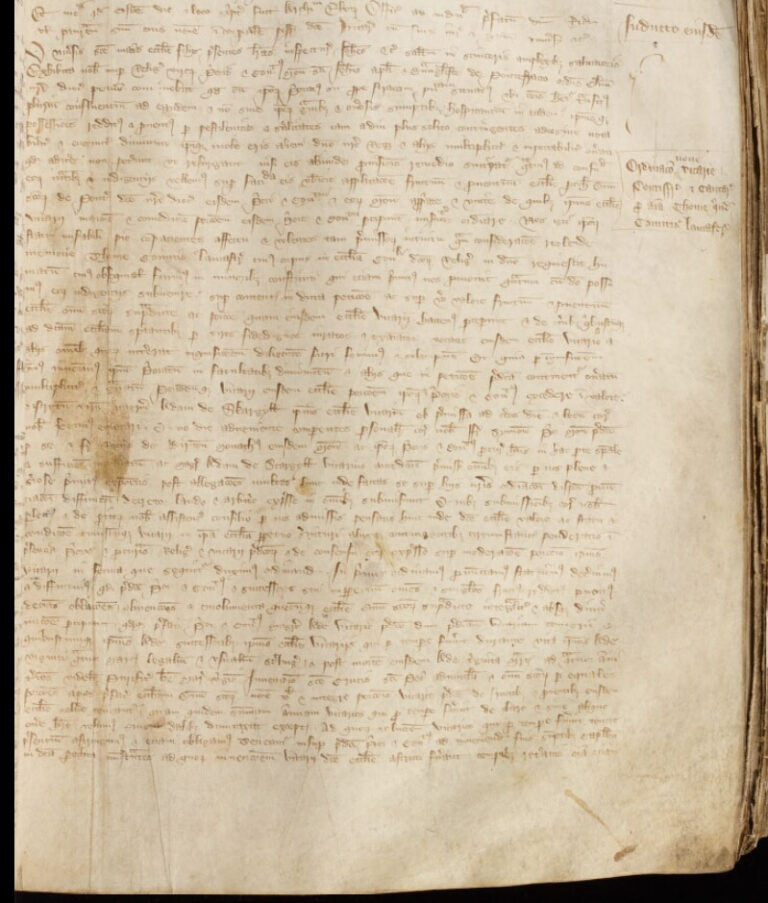

I was particularly fascinated by the ordination of the vicarage of the parish church of Pontefract in the West Riding of Yorkshire found in Archbishop John Thoresby’s register from November 1361. Though this is not unknown, it lays out in intimate detail the provision for a chantry to sing masses for the soul of Thomas, late earl of Lancaster (Borthwick Institute for Archives/York Diocesan Archive/2/Abp Reg 11, ff. 109r-v).

Thomas had been beheaded in his castle at Pontefract for treasonably making war by unfurling his banners against his cousin the king in March 1322. Since that time a cult in his memory had taken root locally, and the chantry was founded upon the petition of the prior and convent of the priory in Pontefract, which Thomas had endowed during his lifetime. This comes nearly forty years after his death and is evidence of enduring local devotion to the Lancastrians and possibly of resistance to tyrannical kings.

Intriguingly, entries from the same register reveal further dissent from authority (BIA YDA/2/Abp Reg 11, ff. 89v-90r): the dean of Pontefract was ordered in January 1357 to warn the community of the town to attend the church of the Dominican friars following complaint by the prior that certain people were holding ‘conventicles’ and many parishioners were no longer hearing mass, sermons or other divine services. Faith at the local level in the North is something our project is very much focused on.

What are the next steps in your research?

We have just entered the final year of the funded phase of the project. We are now in a position where the website has lots of indexed data from the York registers available for researchers to search and browse. There is still a good deal of material to upload and to index to project standards, however, although we are uploading new material from discrete sections of individual registers as we progress. Similarly, Jonathan has gathered an awful lot of first-rate material from The National Archives’ medieval collections, and we are now in the process of making that available and searchable.

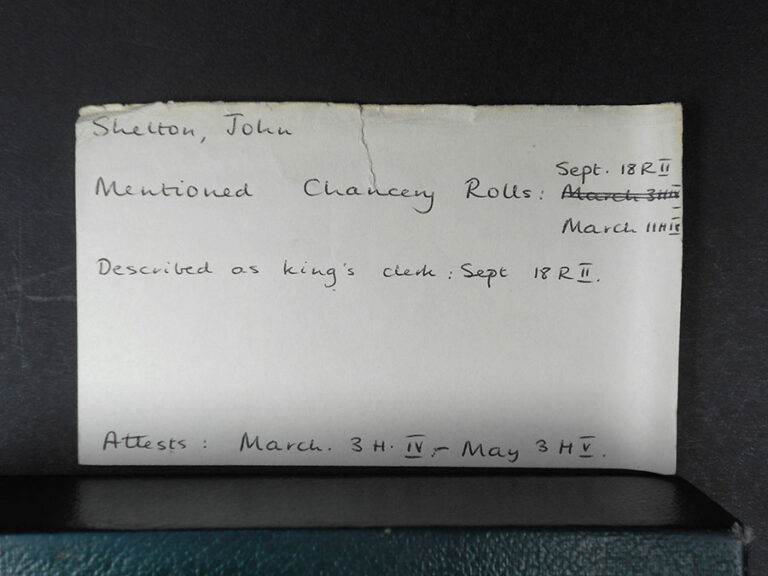

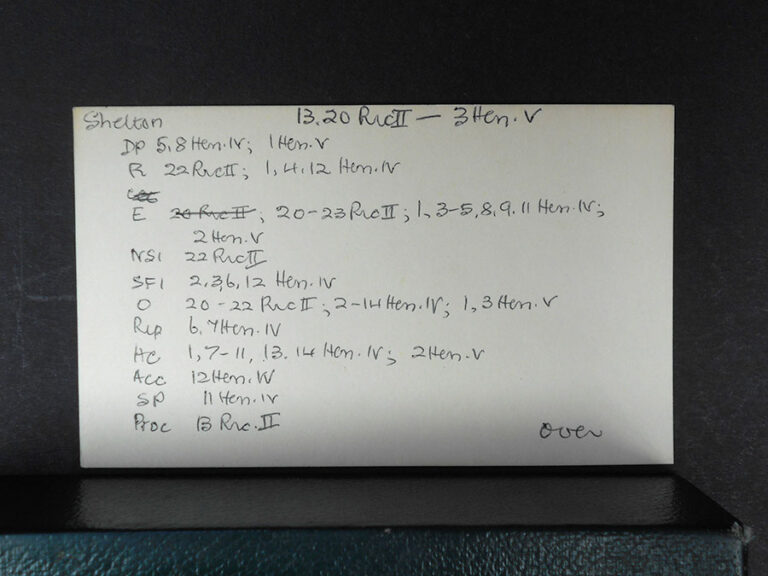

One recent bit of work has been to photograph the Chancery clerks card index in the Map and Large Document Reading Room at The National Archives. This will guide us to particular individuals of interest to our research and potentially widen the scope of series to be sampled in the project. So we would encourage researchers to visit, have a dig around and let us know what they think by emailing tnorthernway@york.ac.uk.

The accumulation and merging of data will allow us to address the research questions. We are currently working on a couple of research articles for publication, but our major next step is to work on the project monograph that will synthesise our research and hopefully make a major contribution to scholarship.

At the same time, Jonathan is working away at producing transcripts, translations and calendars of National Archives records for publication in a source book for Ecclesiastical Records at The National Archives, which aims to guide researchers through the network of complex processes in medieval ecclesiastical and royal administration and provide exemplars of key record types and gather together material relating to a number of topics.

What is something you wish all medievalists knew about this period?

I know I’m biased, but the 14th century is the most interesting in English/British history. In many ways it is a century of terrible calamity, scarred by almost incessant warfare, famine, and epidemics that affected both animals and humans. The devastating effects of the Black Death and its subsequent waves is very well attested in the long lists of institutions of clerks to new benefices made vacant by the death of their predecessors that appear in bishops’ registers and government records. And at the top of society, the deposition of two reigning monarchs as part of bitter civil wars (Edward II in 1327 and Richard II in 1399). But one constant is the dedication, hard work and innovation of professional administrators in very trying circumstances.

While we shouldn’t think of the men who staffed royal and (archi)episcopal administrations as the equivalent of modern, dispassionate civil servants, the expansion and development of the English state (militarily, fiscally, legally, politically or even culturally) was to some degree predicated on the educated cohorts of men manning chanceries, exchequer and the law courts throughout the country and beyond.

What are the most important ways that this research contributes to our understanding of the North, and UK history more generally? Why is this culturally significant?

The ‘North’ as a political, cultural and even economic entity is rarely completely out of the headlines. This year has been no exception with controversies surrounding the nature of lockdowns apparently more adversely affecting communities north of the Trent.

The Northern Way project aims to provide more historical context for concepts of northernness and northern identity glimpsed through the lens of the records of the northern province and its interaction with the state. We are not aiming to define or redefine ‘the North’, but, as the 14th century was a period during which notions of ‘England’ and the ‘North’ were developing, we hope to better understand what place northern England took in political culture and what it meant to be English.

Did the execution of Archbishop Richard Scrope in 1405 at the head of a northern rebellion against King Henry IV really magnify a growing difference between north and south? Or, conversely, was this an aberration at the end of a century during which successive archbishops of York and generations of northern clerks had made significant contributions to royal government – perhaps even imprinting it with a northern stamp?