Our Research Exchange series features interviews with staff and researchers across The National Archives in which they discuss their new discoveries and their work’s potential for impact. The purpose of the series is to highlight and demystify the research we do and open up new ideas and discussion.

In this edition of the Research Exchange, PhD student S L Grange discusses their work on the project ‘Letters of No Moment’.

Letters of No Moment

Tell us about Letters of No Moment – what is the project and what is the meaning of the title?

Named after the term used by previous High Court of Admiralty (HCA) clerks, translators and archivists for correspondence and personal papers not considered of relevance to a case, this project seeks out the marginalised, peripheral (and often female) voices that drift through the miscellany of the HCA’s papers.

The legal proceedings and international negotiations of prize-taking, piracy, trade and politics might be the most apparent and sizeable areas of interest in the HCA collection. But in among these predominantly white, male authors, protagonists and notable persons, we glimpse those other/othered, subaltern bodies and lives as they pass briefly through the frame. A hasty note from a struggling businesswoman, a dispute between two working widows, a community of Portuguese migrant women fighting for compensation, the third-hand story of a French convert to Islam and her children aboard a captive ship, a shipwright’s wife being granted power of attorney …

Letters of No Moment collects these fragments, and both generates and records conversations between me – a queer AFAB artist – and these long-past lives, all lost together in the archives. Following the bodies and material traces as much as the words, Letters of No Moment seeks to ask and maybe answer some questions about what we choose to keep, whose stories get told, how bodies are archives too, the ways in which patriarchal, white-centred structures erase and devalue the Other, and how we might learn to listen differently to the past, and the ghosts our archives create. Producing poetic responses to direct contact with the archive documents, Letters of No Moment is a creative and emotive call-and-response between the then and the now, channelled through a queer feminist lens.

What drew you to this project?

I suggested a creative project as part of a broader placement with the HCA papers project, as I’m primarily a poet and theatre-maker, delving into archival work as part of a PhD project. I came onto the placement knowing I would be generating some kind of creative response but wanting to find out what that was after spending time with the collection. I was told about some letters written by 17th century nuns in one of the HCA boxes which had been classed as ‘papers of no moment’, and I was really taken with the term, as it holds a double meaning that includes a kind of timelessness, as well as highlighting what (and who) is or isn’t considered historically important.

What characters did you discover in these records? What was your process for drawing their stories out, both academically and artistically?

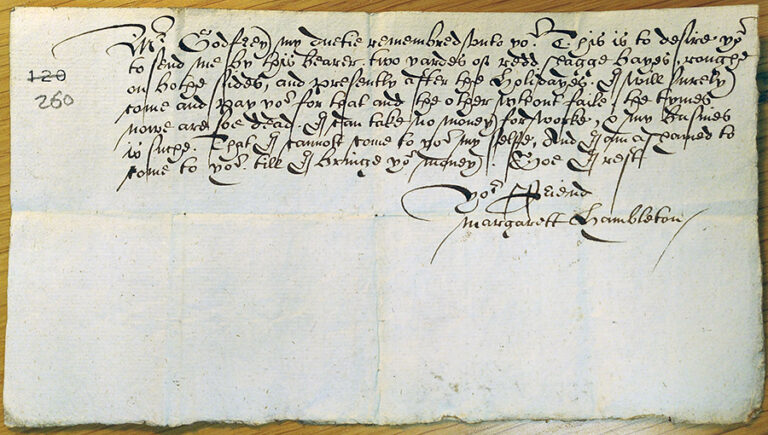

There were lots of fascinating characters in the records – this small collection of poems represents just the tip of the iceberg! I was especially drawn to the note from Margarett Hambleton to William Godfrey, as this is the only document penned by a woman in the six or so boxes I catalogued. It’s undated but came with big heap of papers that were all concerned with debts owed to William Godfrey, merchant Tailor of London, between around 1620 and 1630. We don’t know why they’re in the HCA papers as they don’t obviously connect to any of the cases. I was struck not only by Margarett’s meticulous hand but by the sense of a woman in charge of herself. Unlike all the other women who surfaced in these papers, Margarett is not categorised as a widow or wife – she doesn’t exist only in relationship to a man. She is running her own business, and the note contains a poignant mix of assertion and humility. I also don’t know what ‘two yards of red shag baize, rough on both sides’, would have been used for so if anyone reading has any suggestions, I’d love to hear them!

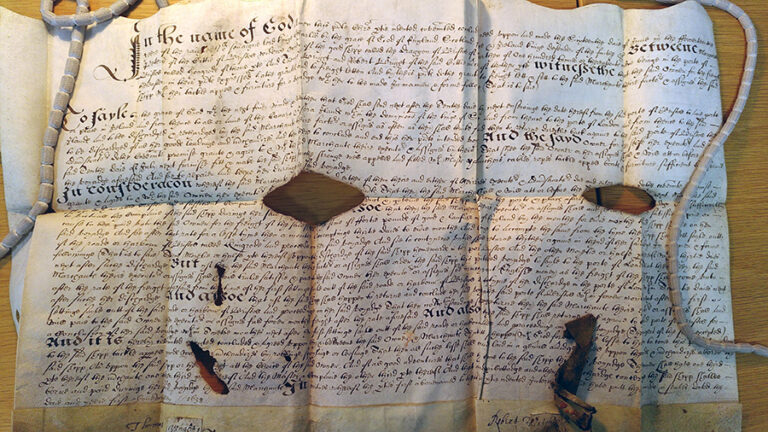

My process is slightly esoteric – I think of the document as a stage on which I can meet the other bodies implicated in it – a kind of entangling of my life with theirs. That might be the person who’s written the words, or the stories that emerge from between the lines, but it also pays attention to the material; the paper-makers, the livestock whose skin makes the parchment, the ink-makers, the quill suppliers etc. It’s a kind of imaginative time-travel that centres an embodied response and has a respect – and even love – for the past lives connected to the archival document. Mostly I try to let go of myself and allow the more marginalised voices to come through. That sounds like a seance, and to be honest it’s not that far off. Hilary Mantel talks about working ‘with real people who happen to be dead’ and this is the way I’ve developed to hold that collaboration.

What are some of the main themes in your poems? Do any topics come up repeatedly?

Because the poems focus on documents that implicate women, ideas of power, autonomy and resistance come up a lot. I wanted to approach these people with a focus on where they had agency and what it meant for them to be – for the most part – at work in men’s worlds. There’s also a sense of global movements – there’s more than one complex immigration story in these papers. And of course, ships, seafaring, salt, and the value of both goods and lives comes up too.

What has been your favourite discovery so far?

Apart from the papers that I’ve worked with to create the Letters of No Moment poems, my favourite finds tend to be the mistakes and marginalia of the collection. There’s something very thrilling about an ink blot leaving me a 400-year-old fingerprint, or the doodles and absent-minded mark-making that makes me feel incredibly connected to the humans who worked on these documents centuries ago. The subject matter might be fascinating for a naval historian, but the fact that people got bored in meetings and felt the impulse to express that with their pens and leave some kind of mark behind is such a vivid connection. I also enjoyed a list of job titles from the 1630s Kent coast that included ‘marshmen, sandmen and riddlers’, and a letter from someone in Plymouth to an early colonist in Virginia asking him to send home ‘2 flying skwirrels’. On one level it’s a very funny request, but on another you can unpack this one simple line to find a world of complex and vexed histories, attitudes and activity.

What is the most significant thing you’ve learned about this historical period during this project?

How incredibly complicated it all was! Not only how much more complex than imagined were the trade connections and routes between Europe and North Africa, but also the way ripples of civil war turn up as Royalist v Parliamentarian prize cases, the traces of the early days of the colonial project impacting Virginia and Barbados, disputes about oyster-fishing rights in Kent and Essex, and the ever-changing rules about who can take whose ships as prize – showing the endless shifting disputes between European powers. All this big history gets filtered down into arguments about cargoes of pilchards or lost pewter, or lists of what crews got paid. In the end, you get these lists of names of real people who probably aren’t on record anywhere else, but whose lives are affected hugely by the big narratives.

How do you think your poems and your interpretation of these records will be received by different audiences? What might they learn?

I hope that they open a space in people’s imaginations that allows a more vivid connection to marginalised lives. Poetry can be a very open, gappy form – it hints at things rather than providing bald facts, so it allows for more questions than answers. If these poems lead to someone questioning assumptions about the past – be that the nature and status of women’s work, or national identity, or simply how it felt for an everyday, otherwise-anonymous person, to be living in the early 1600s.

Can you see this project leading to others in the future? Are there any other research opportunities these records present?

I would love to expand this project and create a full poetry collection – there were so many documents and characters that I didn’t have time to work with. I would also love to spend some time finding potential queerness/queer history in these archives.

The HCA papers are incredibly rich and offer so many research areas – for me, especially the earlier papers hold so much information and inspiration for anyone wanting to look into early colonial activity, North African connections and a pretty dusty (and salty) corner of the English civil war/revolution. The somewhat miscellaneous nature of the collection means there are always surprises, and the cataloguing work so far has only scratched the surface of the ways in which these documents connect to other areas of the collection and the archive more broadly.

What has this project taught you about using archives for artistic practice?

That there is always a rich human life waiting to have a conversation with you, no matter how dry and official the document might seem.