Thinking about the medieval period often conjures up images of treason, disease, war and rebellion. The north of England in the 14th century was an area where all of these were almost ever-present, as well as being a region of great change. But it was also a place where life was dominated by two great powers – the royal government, led by the king and his ministers, and the Church, led by the archbishop of York.

These two powerful forces held sway over many aspects of life in medieval England, sometimes competing but generally working together, sharing information and personnel, regulating the life of the medieval north and defending it from threats, both internal and external, spiritual and temporal. This was a formative period in England’s history, and while it cannot be overstated how influential the Church was, particularly in this region, the personalities and actions of the people involved are not yet well understood.

Below, Jonathan Mackman unpacks the research he conducted as research associate with The Northern Way project, an AHRC-funded project being conducted in collaboration with the University of York and York Minster.

This is the first in the Research Exchange blog series of interviews with researchers across The National Archives, discussing their new discoveries and their work’s potential for impact. The purpose of the series is to highlight and demystify the research we do and open up new ideas and discussion.

Can you give a bit of background on The Northern Way project, and its aims?

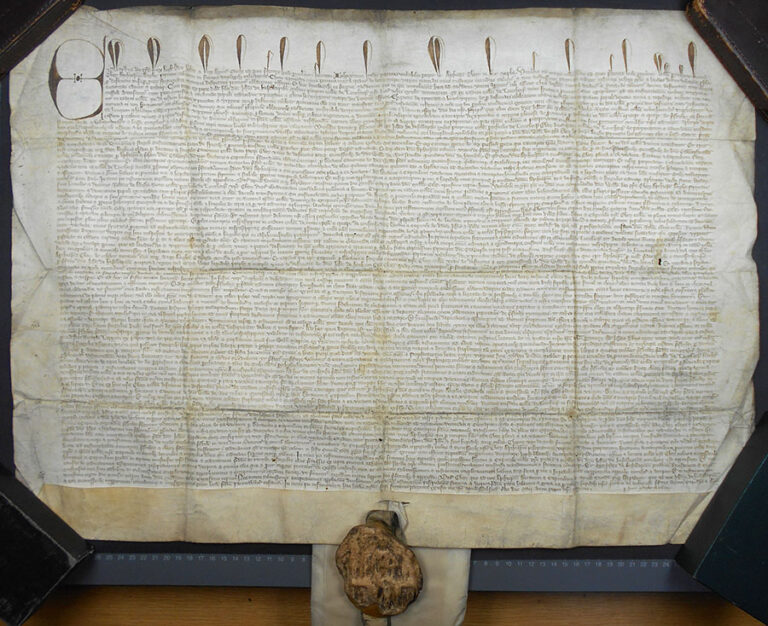

The Northern Way project is part of the wider York Archbishops’ Registers Revealed project, based at the Borthwick Institute for Archives at the University of York, which is making the registers of the archbishops of York available to a wider audience. The first stage of that project involved the digitisation of all the registers surviving in York, dating from between 1225 and 1650, and those are now freely available on the project website. But despite this, they still remain accessible only to those with the skills to read and interpret them.

The aim of The Northern Way project is to remedy that, by providing fully-searchable English summaries and indexes to the 14th-century registers, and to explore the wealth of information contained within them, through traditional publications and through a range of workshops, videos and other media. We will be using this newly-accessible data to answer a series of research questions about the late-medieval northern Church, particularly looking at its personnel, its interactions and confrontations with the royal authorities, and whether any specifically ‘northern’ attitudes and approaches affected its actions during this turbulent century.

How does your work fit into the research being conducted at University of York?

The registers are just one window into the activities of the medieval archbishops of York, and of the northern Church in general, showing the internal and external correspondence of the archbishop and his officials. But the Church did not work in a vacuum. It had extensive connections with the wider world, and particularly with the royal, secular authorities.

In areas such as property, taxation, warfare and the law, the Church was in constant contact with the Crown, working together and sharing information, and these left their mark within the government’s records.

My role has been to search through the collections at The National Archives looking for the ‘other side’ of these stories, highlighting complementary records showing how the two administrations worked together (or otherwise), shared information and personnel, and how individual archbishops interacted with the king and other national and regional powers. By linking these records, particular issues can often be better understood, and the reasons behind specific actions can be discovered.

Can you discuss some of the key individuals that come up in this research?

Our main focus has naturally been on the archbishops themselves: their personalities and activities, and also their involvement with, and participation in, the royal administration. They were a diverse group, some being northerners themselves, others little more than royal placemen.

William Melton, archbishop between 1316 and 1340, is one of the most interesting characters. A native Yorkshireman and a supporter of Edward II, he even helped to defend the north against the Scots at the disastrous Battle of Myton in 1319.

Conversely, Archbishops Alexander Neville and Richard Scrope both suffered for their involvement in national politics. Neville, a very abrasive character, became embroiled in the dispute between Richard II and the Lords Appellant, and in 1386 was accused of treason and fled into exile in Brabant. Scrope allied himself with the Percy family in their rebellions against Henry IV, and after joining the rebel army in 1405, he was arrested, tried and became the first archbishop of York to be executed.

But of course, we are encountering hundreds of individuals, from senior clerics to peasants and artisans. Our favourite so far has undoubtedly been Joan of Leeds, a nun from York who faked her own death and fled her convent in 1318. The albeit sparse details of Joan’s story have prompted numerous articles in national newspapers and other media, and even inspired a musical play, performed at a London theatre in December 2019. Sadly, she hasn’t appeared in any records at Kew yet, but we’re still hopeful!

What datasets and records are you using for this research?

The sheer level of interaction between the Church and state in our period means that material appears in almost every medieval series at The National Archives. We have focussed particularly on those series which have the most direct interaction with the archiepiscopal administration, and the greatest potential for our research.

This has naturally included some of the most extensive and accessible series. The Patent (C 66), Close (C 54) and Fine rolls (C 60), which show the day-to-day working of the royal government, are available in English calendars, while other major series, such as the Ancient Petitions (SC 8) and Ancient Correspondence (SC 1), have particularly full entries in the Discovery catalogue, and give closer insights into the Crown’s interaction with other individuals and bodies.

We are also sampling many of the larger unpublished and uncatalogued series, such as the vast plea rolls of the royal courts, while for smaller series I have been able to make comprehensive surveys of material relating to the northern province.

For instance, series C 85 comprises requests for the arrest of people who had been excommunicated, something the church authorities could not do themselves, while series C 84 records the various stages in the appointment of senior clerics. Similarly, C 81 includes requests for the Crown to arrest renegade monks and nuns. Many of these documents can then be matched up with entries in the York registers.

Other series, such as Ecclesiastical Miscellanea (C 270), have been particularly useful, and I’ve also looked through some largely-uncatalogued series, such as Ecclesiastical Certiorari (C 269), which contains the results of royal requests for information, and the Chancery Recorda files (C 260), many of which relate to legal cases and especially the issuing of pardons.

One of the most important aspects of this work has been tracking particular stories through the various series, in order to build a fuller picture.

What are your favourite or most surprising discoveries in your research thus far?

The research has uncovered lots of individual stories, shedding new light onto well-known subjects or recounting newly-discovered ones. For instance, two excommunication records list the names of all the monks of Rufford Abbey in Nottinghamshire, who were excommunicated after failing to defend a lawsuit.

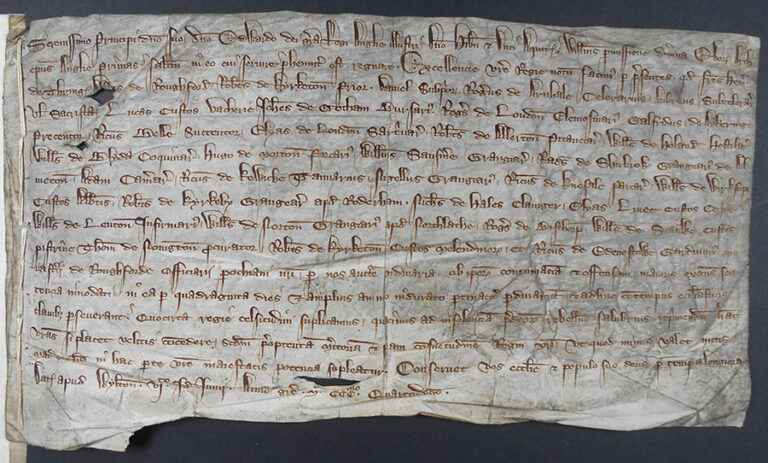

Such lists are unusual, and rarely survive in any context. Analysis of a letter among the Ancient Correspondence, often used as a key source for the events surrounding the return of Edward II’s favourite Piers Gaveston to England in 1312, has also allowed us properly to identify the writer and recipient for the first time, and this will be the subject of a forthcoming conference paper.

Other documents may be of lesser historical importance, but can highlight individual aspects of medieval life. One document recounted the story of an official of Selby Abbey, pardoned for accidentally killing a man who, after being prosecuted for affairs with multiple women in the town, tracked the official down and chased him around the abbey kitchen!

And of course, The National Archives also holds many chance survivals, such as two foundation charters for chantries in the collegiate church of Lowthorpe in Yorkshire (E 328/373, 387). The text of these is also recorded elsewhere, but these are the impressive original charters, drawn up for the parties and later returned to the government archive for unknown reasons.

What are the research outputs and what impact will these have?

The most significant output of the project will be the additions to the York Archbishops’ Registers Revealed website, which will include thousands of index entries for the registers and the data being collected at The National Archives. The project will also be producing two books – one examining the role and influence of the archbishops, and a guidebook to related material.

We have been running a series of workshops (all now taking place online) introducing various groups to the archbishops, the registers and the documents at Kew, and the project website also includes a series of blog posts, videos and presentations on various aspects of our work. And of course, the story of Joan of Leeds has quite literally brought our work to a worldwide audience!

What future projects or partnerships could this open up in future?

As noted earlier, The Northern Way is just one strand of a much larger ongoing project at the University of York, and it is intended that further future projects will look at other periods and different aspects in the history of the archbishopric. Another related project has already prepared a new edition of the earliest surviving register, that of Walter de Gray, archbishop between 1215 and 1255.

Other future partnerships will hopefully include the archives of other ecclesiastical bodies across the country, in both the northern and southern provinces, and could lead to the digitisation and analysis of similar records in other dioceses.