Our Research Exchange series features interviews with researchers across The National Archives, where they discuss their new discoveries and their work’s potential for impact. The purpose of the series is to highlight and demystify the research we do and open up new ideas and discussion.

Engaging Crowds

Below, Research Software Engineer Bernard Ogden discusses his research conducted as part of the Engaging Crowds project, an Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded project, part of the Towards a National Collection research programme.

Could you give an introduction to the Engaging Crowds project and your role in it?

‘Engaging Crowds’ is a project led by The National Archives, in partnership with Royal Museums Greenwich, the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and Zooniverse at the University of Oxford. It investigates engagement of volunteers in citizen research projects – which is one form of ‘crowdsourcing’.

As part of the project, we developed three new citizen research projects on the Zooniverse platform. These projects feature a new indexing tool designed by Zooniverse which gives volunteers more control over which records they work on, rather than seeing documents at random.

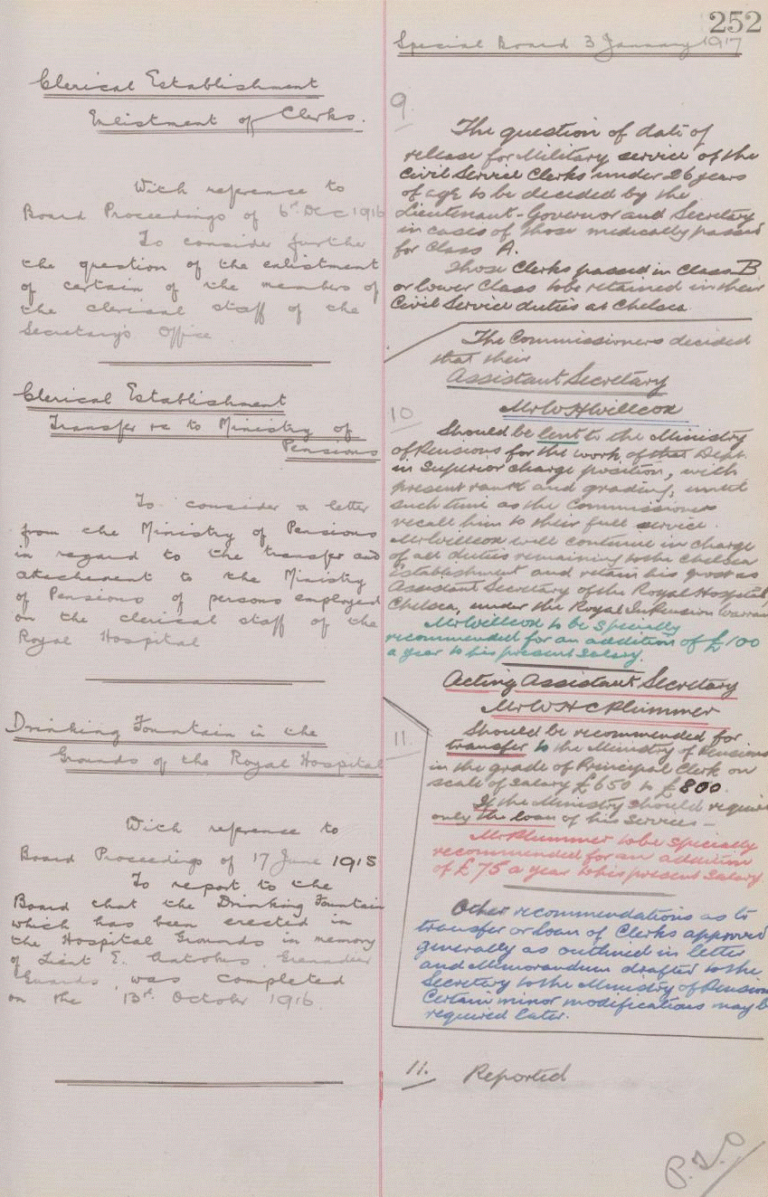

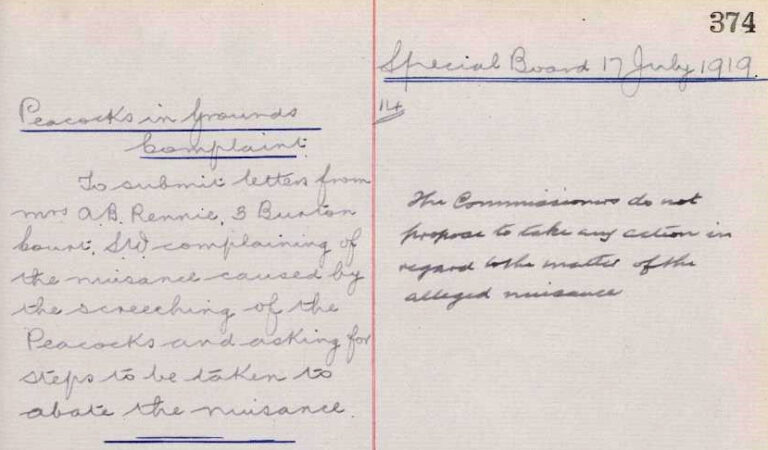

I originally got involved to develop and manage The National Archives’ project Scarlets and Blues, working with Will Butler, Head of Military Records. We asked volunteers to transcribe early 20th century minute books of the Royal Hospital Chelsea.

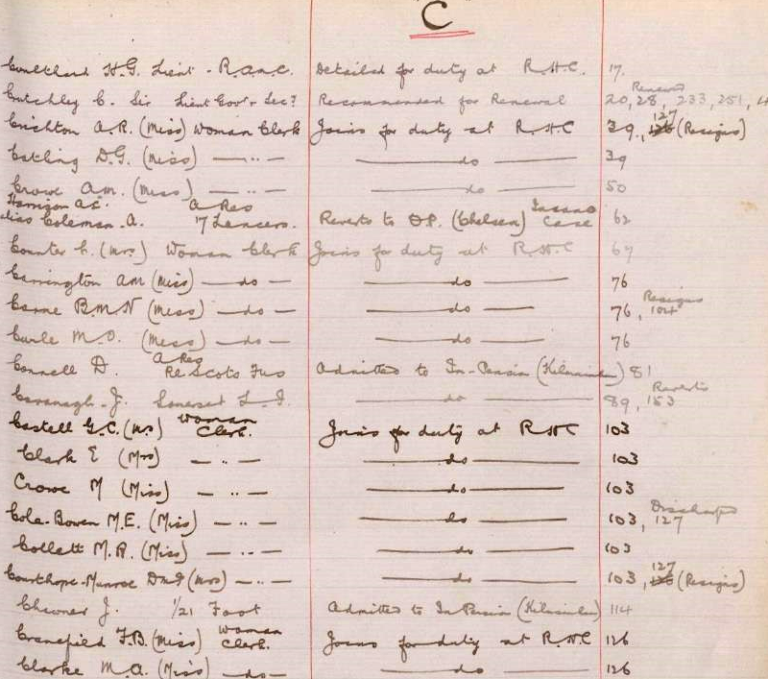

I’ve also worked on the data that has come out of the project. Zooniverse projects collect multiple transcriptions per record: we then compare the transcriptions and ‘reconcile’ them into a single best transcription. I am using both Zooniverse tools and code by Mark Bell, another colleague, to do this reconciliation.

Finally, the purpose of this project is to study the engagement of citizen researchers. To give us some quantitative insight into that, I have done some analysis of the activity logs across all three of the ‘Engaging Crowds’ projects. I’ve looked mainly at when volunteers tend to work on projects and how numbers of volunteers change over time.

One of the nice things about The National Archives is that it is a very collaborative working environment. I’ve mentioned a couple of colleagues above, but throughout I have been working with many other members of our staff, as well as the cross-institutional ‘Engaging Crowds’ team.

What is the most surprising or interesting thing you have discovered?

There have been loads of discoveries along the way but I think that the most surprising one to me was just how enthusiastic people are to help with research. The ‘Scarlets and Blues’ workflows were quite tricky and took a lot of time to complete compared to typical Zooniverse workflows, but enough volunteers took them on and stuck with them to complete the whole project in just a couple of months.

The most interesting thing was the challenge of creating a project that was both engaging and methodologically sound. With transcription there are a lot of questions about how to translate the text on the page into text on a computer. Should I expand abbreviations? What if a word is crossed out? What do I do if I’m not sure about a word? It goes on and on. It can seem pedantic, but if we don’t know what rules were followed to make a transcription, then we become that much more uncertain as to whether or not it is a true representation of the original record.

We did our best to create transcription instructions that were as simple as possible for volunteers to follow and made sure to signpost how they could ask questions via the Talk forum. The volunteers were able to contribute to the instructions in this way too by offering solutions when they encountered something unexpected.

However, we cannot expect that all of the volunteers have read all of the instructions or followed them exactly every time. Part of working with a crowd of volunteer researchers is accepting some relaxation in our control over how the work is done. The data might contain some extra uncertainty but, so long as we can work with that uncertainty, it is still more data that we can use – and that we otherwise would not have at all. Thinking about working with uncertain data, and about that trade-off between engagement and control, is very interesting to me.

What was your favourite aspect of this project?

It has been quite a multifaceted project and that variety is one of the nice things about it. But it is easy to pick the part that I enjoyed the most: I loved working with the volunteers on the ‘Scarlets and Blues’ Talk forum. I enjoyed helping them with questions, solving problems together and seeing the interesting things that they highlighted in the records. Best of all was when they shared research of their own that had been inspired by something that they had read. I am so grateful to everyone who took part in the project for sharing their time, energy and expertise with us.

What are the next steps in your research?

We’re working on our final project report right now, which will be available via the Towards a National Collection website. We’ll also be making available our data processing scripts and the raw data from all three ‘Engaging Crowds’ projects on our project website. After that I’ll need to continue working on the data reconciliation from ‘Scarlets and Blues’ to transform the original volunteer transcriptions into additional record descriptions for our catalogue, and into a dataset that can be used for research.

Beyond ‘Engaging Crowds’, I would like to explore more around the community involved in citizen research projects and around the outreach and engagement aspects of citizen research. It is not just about extracting data. Citizen research has great potential to engage the public in deeper ways with historical research and I would really like to work more on making it more of a two-way process.

What is something you wish to share with other software engineers working in research?

That’s a tricky one. The most ‘software-shaped’ part of the project has been reconciling the volunteers’ classifications, but so far that has been quite straightforward – I’m mainly building things out of other people’s components. I don’t think I have any software insights from this project other than the commonplace observation that research software seems to be quite fragmented and ‘single use for a single project’.

I’m not sure what the solution to that is. Part of it is probably to invest more in more general-purpose tools and libraries, building up the open source software community for cultural heritage. Another idea which I’ve heard here and there is to think of our programs as examples for how to do things, so that we can build exactly what we need based on one another’s recipes – the cookbook approach. We will be sharing the code and data we’ve created on the project, so some recipes for working with Zooniverse data will be one output from ‘Engaging Crowds’.

What do you think were the key takeaways about how this research contributes to our understanding of cultural heritage or history more generally?

Citizen research is a particularly interactive form of outreach: we are not just presenting an understanding passed to an audience, we are working with volunteers to develop that understanding. The volunteers are a multitude of voices, each with their own motivations, interests, perspectives and expertise. We have heard some of these voices in a ‘Voices of the Volunteers’ workshop we ran in December 2021, in a survey of Zooniverse volunteers and especially in directly communicating with them on our project forums. The more volunteers that we can engage, and the more that we can engage them, the more of these voices we will hear. This is quite different from thinking in the abstract about audience diversity. It can help us to better understand our audience and it can also highlight for us where we are thinking too much inside the limits of our ‘cultural heritage professional’ bubble. I think that this direct contact with some of the individuals who make up our audience is a really valuable part of citizen research.