For anyone with mining ancestors or connection to the mining industry, the anniversary of the Oaks Colliery catastrophe is an event worthy of remembrance.

Although it occurred 156 years ago, on 12 and 13 December 1866, the loss of 361 lives in this pit near Barnsley remains the event with the worst death toll of England’s many mining disasters. Four hundred and thirty nine deaths, in an explosion at the Universal Colliery, Senghenydd near Caerphilly on 14 October 1913, is still the UK’s deadliest underground accident, and even across such a long period of time, there were common factors between these and many other serious mining incidents caused by ignition of explosive gases.

The recent decision on opening a new coalmine near Whitehaven in Cumbria has put mining and its products back into the public debate over climate change, sustainable industrial jobs and energy. Coming near to the anniversary of the Oaks disaster, it reminds us also of the hazards inherent in this country’s long mining heritage.

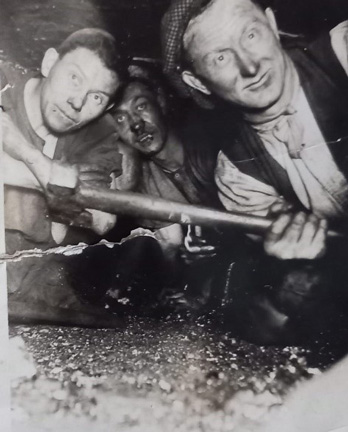

On 12 December 1866, the first Oaks explosion at around 13:15 killed 334 of the 340 men and boys working underground. Twenty miners were brought up alive but only six survived their injuries. There were 27 more deaths the following day, when volunteer rescuers who had descended were killed on or near the downcast pit bottom, as attempts to excavate destroyed workings ignited new pockets of gas. They included senior local mining engineers, managers and deputies like Parkin Jeffcock and David Tewart, who had not been underground on the first disastrous day.

John Mammatt and Thomas Embleton went down on 14 December to bring up a sole survivor from this group. One of this rescue party, the night fireman, Matthew Haigh, averted 60–90 more deaths by noticing how a change in the wind direction would hinder the ventilation of the damaged mine. He raised the alarm and ensured that men were held on the surface. The gathering crowds called Haigh a coward for refusing to send them down, but his decision was vindicated as the secondary explosions started.

A memorial erected by public subscription in Ardsley churchyard in 1879 commemorated all the dead, while a second monument put up near site of the mine in 1913 highlighted the efforts of the rescuers. For the 150th anniversary, sculptor Graham Ibbeson produced another poignant and powerful memorial image that now stands in Barnsley.

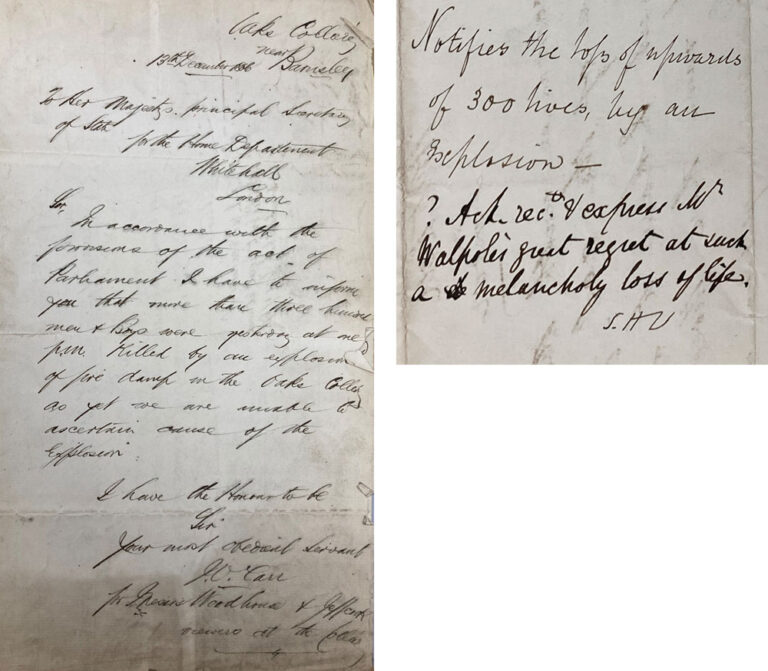

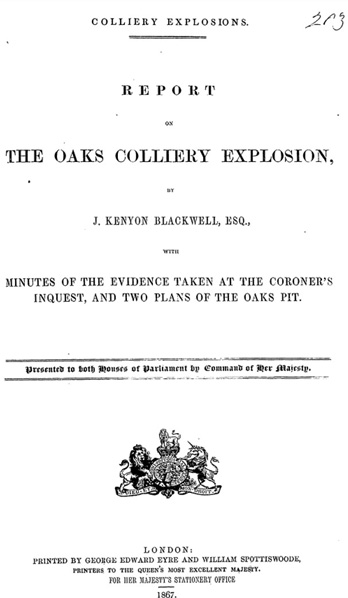

The inquest, by coroner Thomas Taylor, and the report to Parliament of a retired mine inspector appointed by the government, John Kenyon Blackwell, provide the official view. The Home Office file (HO 45/7893) also contains an account by the inspector of Lancashire mines, Joseph Dickinson, who early in 1867 offered his expertise on how ‘fearful accidents’ might be prevented in future.

Other viewpoints were quickly in the public domain, however, as shorthand writers at the inquest and communications by telegraph from reporters at the site within hours of events captured immediate responses and more varied voices – all of which combine as good evidence of the highly dangerous conditions common in coalmines during the Victorian period.

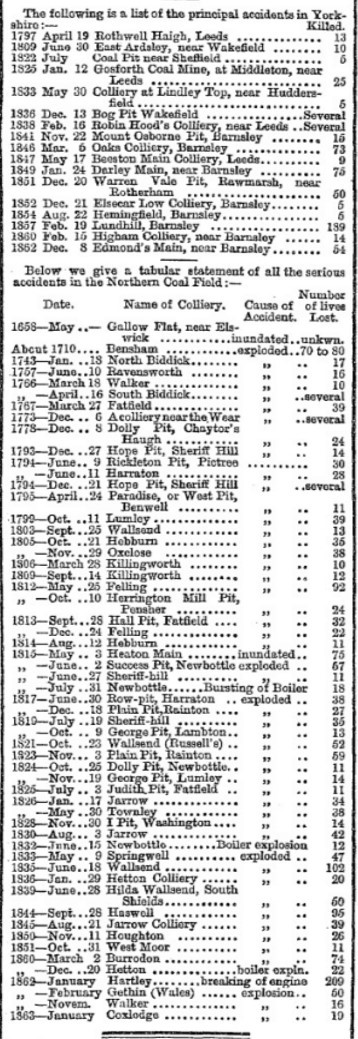

On 13 December 1866, with fires still burning at the mine, the Leeds Mercury newspaper informed its readers that the loss of life ‘will be greater than has occurred at any single time in Great Britain since the Battle of Culloden’. To emphasise this fact, the paper presented a stark table of the death tolls from accidents and explosions in the Yorkshire and north-eastern coalfields since 1658 – at least 500 lives lost in Yorkshire and over 1900 in Durham and Northumberland.

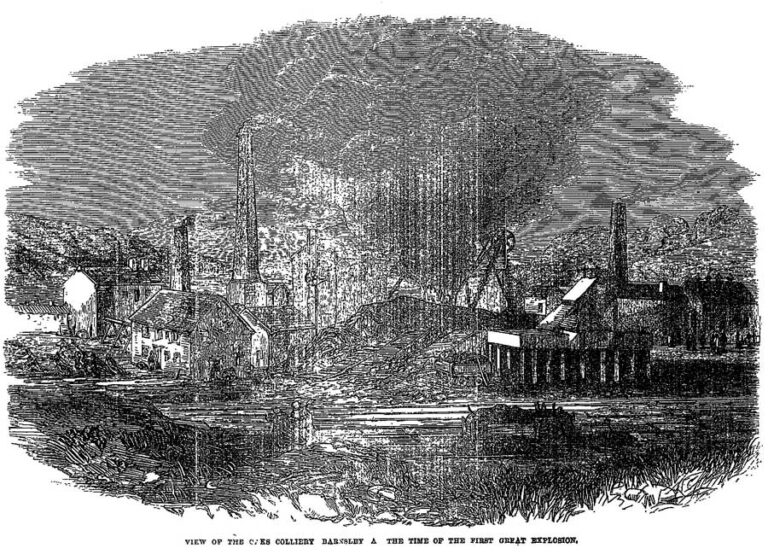

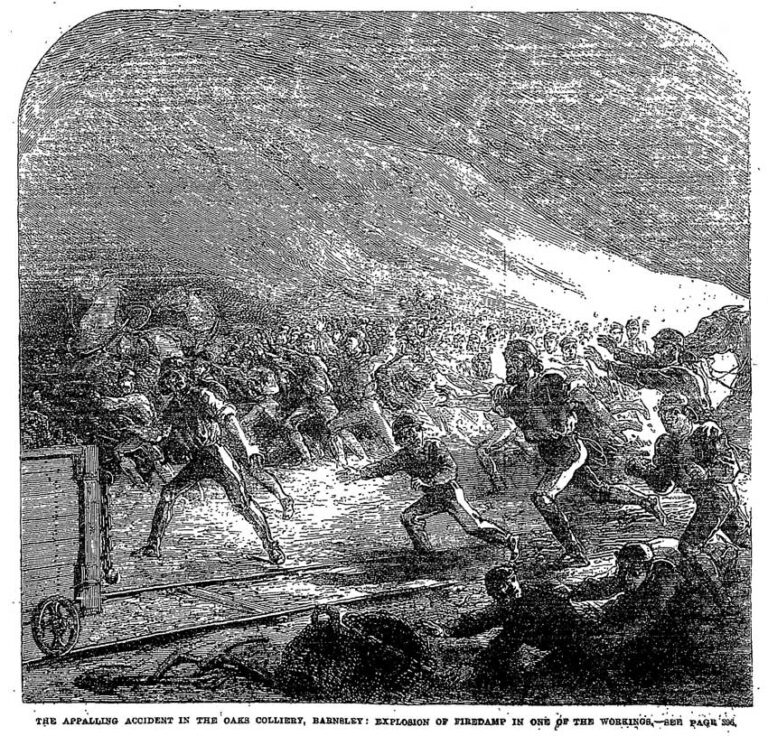

Other journals, like the Penny Illustrated Paper, presented imaginative engravings showing the Oaks disaster unfolding – generating sympathy for the communities affected but also emphasising the accidental nature of the incident rather than implying negligent management.

Discovering the course and cause of events was for the coroner and government officials, but they heard from the same people – miners, relatives, local colliery officials – who spoke to reporters at the scene. With the bodies of so many trapped, the coroner’s first investigation was limited. On 14 December statements began from the relatives of thirteen men and boys who died soon after emerging alive or whose bodies had been recovered after the first explosion – six of whom were aged under seventeen and the youngest, lamp cleaner John McQue, aged only twelve. Two hundred and eighty six bodies were still in the mine. On 20 December, proceedings were adjourned until 7 January 1867, which gave time for Blackwell to travel from his home in Paris to Barnsley.

Visible at the time was the solidarity between mining districts and their associations/unions in understanding the shattering effect that the disaster had in the townships around Barnsley – many others had experienced similar sudden shocks as men and boys failed to return home from their shifts underground.

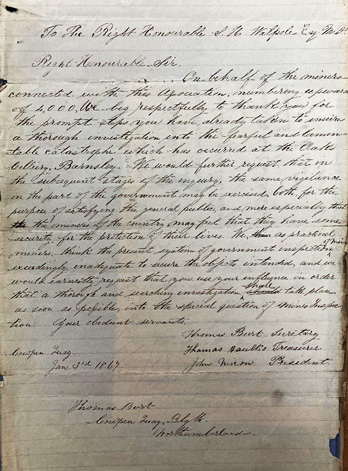

Thomas Burt, secretary of the Northumberland Miners Mutual Confident Association, a union of 4000 members, wrote to the Home Secretary on 3 January 1867, thanking the government for the prompt steps taken to investigate the ‘dreadful and lamentable catastrophe’. Burt, a future MP for Morpeth, reminded Walpole that his Association viewed the present regime of mine inspection as ‘exceedingly inadequate’ and that workers must ‘feel they have some security for the protection of their lives’. Evidently, working miners believed that the system set up by the 1850 Mines Inspection Act had done little to improve underground safety.

The associations looked to find the cause of the explosions in failures of the inspection regime and slow changes to underground conditions by the mine’s owners. Although the scale of the loss at Oaks was exceptional, the undisputed cause of the disaster – the ignition of firedamp (combustible methane or hydrogen) – was a very familiar risk to all mining communities.

In the especially ‘fiery’ seam of the Barnsley region, firedamp was known to escape at a high enough pressure to force back the ventilating air. It also collected and pooled in previously worked areas of debris, called goaves. Airflow through the mine was the key to diluting or removing the gas from the areas where the coal was being cut. It would have had less effect in the goaves.

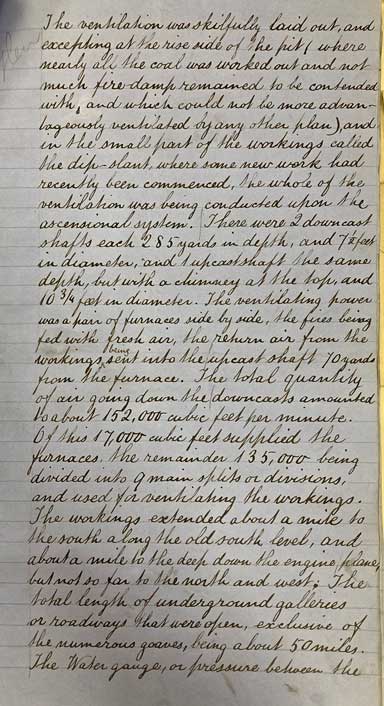

Like all deep mines, Oaks had a system of working the seam and this was analysed by Blackwell in his report. The ventilation was generally thought by the under-viewers to be well set out and effective, although the managing partner, Thomas Dymond, had taken a delegation down on 30 November after reports that firedamp was bad enough to hinder working.

Failure to follow procedures set up to manage the gas risk were quickly blamed for the explosions, but problems with ventilation or provision of good lamps could also have limited what the miners were able to do as they worked the seam. This was where the owners were wary of scrutiny of their responsibilities. A previous explosion at Oaks in March 1846 had killed 73 men and boys. Nine years later, on 19 February 1857, 189 deaths occurred on the same coal seam in a blast at Lundhill in Wombwell.

In 1866, the Oaks mine owners prepared to protect themselves from possible legal consequences by recruiting counsel for the coroner’s inquest. The Home Office took some time before deciding that because the families of the miners had ‘no professional assistance’ it should also, ‘in the interests of justice’, employ a barrister to safeguard the facts in any cross-examination.

The ignition of the gas was believed by some witnesses to be the result of a blown out shot. Naked gas flames were also used as lighting in some parts of the mine, away from the working faces.

Blackwell’s and the coroner’s reports sifted the evidence of ventilation arrangements and of the sounds heard immediately before the blast, the pattern of the explosions and the location of bodies. They and experienced miners concluded that the shot firing and flames were too far from the biggest gas deposits and were unlikely to be the first cause of the miners’ deaths.

Blackwell decided that the ignition probably started on the south dip or headway near to an underground lamp cabin – Thompson’s Box Hole – and ignited a newly released concentration of firedamp through some breaking of rules about relighting lamps. Yet other statements suggested a very well-observed lamp safety regime. The owners were certainly keen to show that their procedures conformed to the 1860 Mines Regulation Act then in force.

The evidence of damage to gates, wagons and the burn injuries on dead miners and ponies all pointed to a blast origin near that location. The investigation reveals interesting details of how the Stephenson and Davy lamps were used with barometers underground and how they responded to the presence of firedamp. Changes to the colour or intensity of flame or the heat of the lamp gauze were the only signs that miners could rely upon, but it was an uncertain process in the dusty and dark conditions at the cutting faces, where the temperature was possibly 48°C at the time of the explosion. The initial fire or blast disturbed enough firedamp and coal dust elsewhere to mix with the ventilating air, fuelling continuing explosions.

Because the entire mine was open and connected underground, there was little to prevent the effects spreading rapidly to all working areas. A far greater number of workers then suffocated as afterdamp (carbon dioxide, nitrogen and carbon monoxide), replaced the combusted firedamp. Nevertheless, although he agreed that a gas explosion caused the deaths on 12 December, the coroner made no judgement on how it had ignited.

Blackwell completed his report by 30 March 1867. He was paid £5 5s per day for his efforts. The Treasury did quibble over payments for him and the official shorthand writer for the time they were sitting at the inquest, but almost £500 was eventually paid out for these services.

There is nothing in the file on assessing the impact on the numerous mining families affected directly nor on provision for their welfare. In 1867, the government did not see these as its responsibility, even if the Home Secretary quickly expressed his ‘great regret at such a melancholy loss of life’.

Any provision was something for the owners to consider as part of their role as major local employers, but the management were unable to name the dead and missing, and the local branch of the Miners’ Association supplied the first list that appeared in the Leeds Mercury on 13 December.

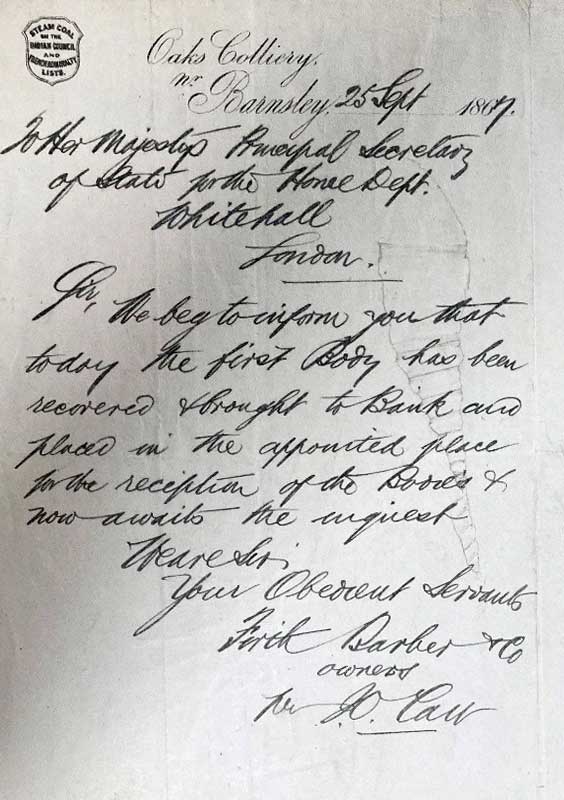

Public campaigns had aided the Oaks families after the 1846 disaster, and similar steps were required in 1866. Membership of the local branch of the South Yorkshire Miners’ Association dropped from 275 to 16 between 10 December and 7 January, forcing reliance on other branches for any immediate support that fellow miners could offer. These struggles must have continued for many months, since it was not until 25 September 1867 that the first body was recovered from the destroyed workings underground.

The government’s record leaves the aftermath of the Oaks disaster at that point, but the list of mining accidents and the danger of firedamp continued throughout the subsequent history of Britain’s coal industry (as shown by the monthly ‘In Memoriam’ section of the Durham Mining Museum website).