Warning: This blog post contains distressing text and images.

Friday 27 January is Holocaust Memorial Day. Together, we remember the millions of victims of the Holocaust and subsequent genocides.

This year, the theme is ‘ordinary people’ and I must admit I have found it rather difficult to stick to it. I will nonetheless share what I found when I looked at the files we hold on the Gross-Rosen concentration camp.

These files focus on the disappearance and presumed liquidation of SOE agents arrested in France, and almost exclusively relate to the main camp – as opposed to any of the almost one hundred subcamps which came under the authority of Gross-Rosen.

An ordinary camp?

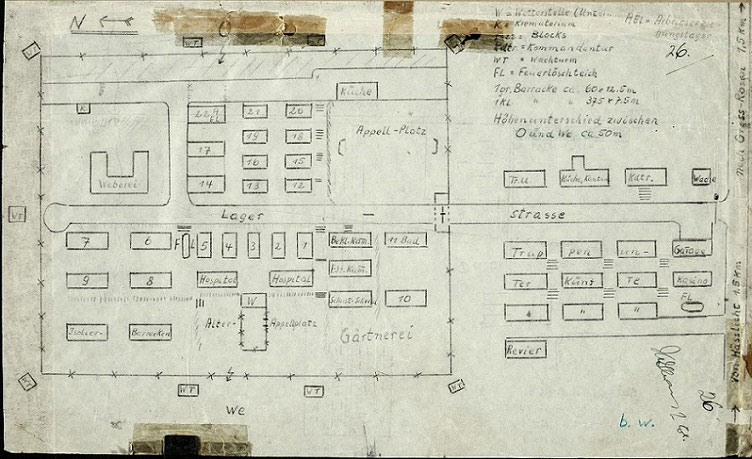

At first, Gross-Rosen was a small camp, about 60 kilometres from Breslau (Wrocław), in Lower Silesia, now in Poland. Built in 1940 as a subcamp of Sachsenhausen to provide labour to the SS-operated Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke GmbH (German Earth and Stone Works), it became an independent concentration camp in 1941. By the end of 1944, about 11% of the people trapped in the Nazi concentration camp system, including over 25,000 women, were at Gross-Rosen or one of its subcamps.

The Schutzhaftlagerführer, or head of the preventive detention camp, Anton Thumann, who would become known as the Hangman of Majdanek, was particularly brutal. Isaak Egon Ochschorn was in Gross-Rosen from June 1941 to October 1942, before being transferred to Auschwitz. He stated:

‘The sport of Commandant [Thumann], favoured in winter, was to have many Jews daily thrown alive into a pit and to have them covered with snow until they were suffocated’.

Catalogue ref: WO 309/456

The camp replicated the Nazi social order, with Jewish prisoners at the very bottom of the hierarchy and isolated from the rest of the prisoners. On 2 December 1941, Ochschorn reported, Thumann gave a clear order: ‘no Jew is to remain alive by Christmas’. In 1942, all the Jewish prisoners were transferred to other camps, mainly Auschwitz. Very few survived (WO 309/456).

Not much higher on the Gross-Rosen ladder were Soviet prisoners. From 1941, Soviet prisoners of war were routinely brought to the camp to be executed. Sometimes by hanging, sometimes by shooting, usually by lethal injections.

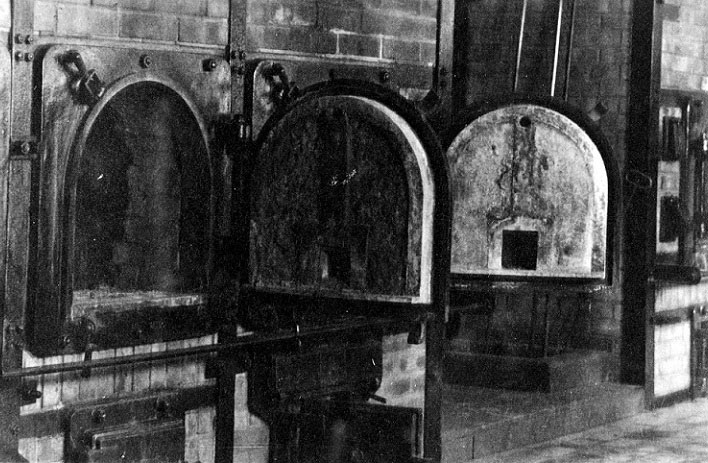

The camp had a field crematorium until a more permanent structure was built to dispose of the bodies. According to statements ‘9 bodies could be burnt at a time’. Until 1943, the death rate was very high. Food rations were very small and although there was an infirmary, there was virtually no medical care. Prisoners working in Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke’s granite quarry had an average life expectancy of five weeks.

The conditions in the main camp started improving (relatively) in October 1943, when Johannes Hassebroek took over as Camp Commandant. By all accounts, Hassebroek was ‘decent’ with the prisoners. He increased food rations, issued a vastly ineffective order forbidding gratuitous beatings, allowed football games, and set up a theatre and a cinema. All ordinary activities which must not give the image of an ordinary prison camp, nor obfuscate the stark reality of what was happening in Gross-Rosen. Hassebroek did improve the camp, but the conditions remained brutal, especially in the sub-camps.

Describing Gross-Rosen during his trial in 1948, Hassebroek stated:

‘There were prisoners there, slave labour assisting the German Government (…). They were not paid. I started getting them pay. Possibly SS got paid for their slave labour. WVHA got the money, not the prisoner, they got up to 10 [Reichsmarks] per week’.

Catalogue ref: WO 235/552

Even under Hassebroek’s somewhat improved regime, executions were frequent. He described them as ‘the only black spot in [his] camp’. Conditions started deteriorating again in 1944. As camps further east were being evacuated, and after the suppression of the Warsaw uprising, the number of prisoners rose sharply. The food rations decreased, more men were packed in confined spaces, and diseases, notably spotted fever and typhus, spread more quickly.

In January 1945, as the Soviet Army was advancing, the SS started dismantling the subcamps east of the Oder river. The main camp was evacuated in February 1945, and prisoners were forced onto death marches to Mauthausen, Bergen-Belsen, Dachau, Buchenwald, Flossenbürg, Dora-Mittelbau or Neuengamme. There was no food, no water, and people too weak to march were killed on the spot. Some prisoners were transported by train, but it wasn’t better – packed in open wagons by 20 degrees below zero, few survived the journey.

The main camp was almost empty when the Red Army finally entered it on 13 February 1945.

‘Two ordinary SS Corporals’ and their Commandant

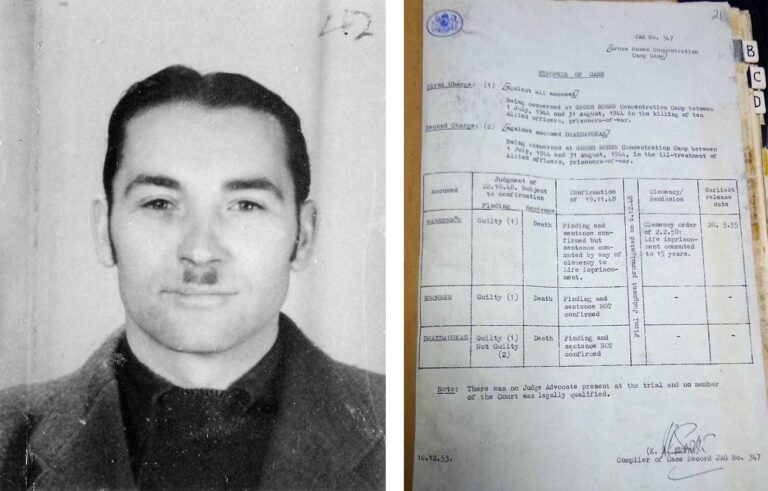

In the summer of 1948, three men were judged by a British military court ‘for the killing of ten Allied officers, prisoners of war’ at Gross-Rosen.

Born in 1910, Johannes Hassebroek joined the SS and became an officer in the Totenkopf division in 1936. He fought in France in 1940, and eventually took over the Gross-Rosen camp on 13 October 1943.

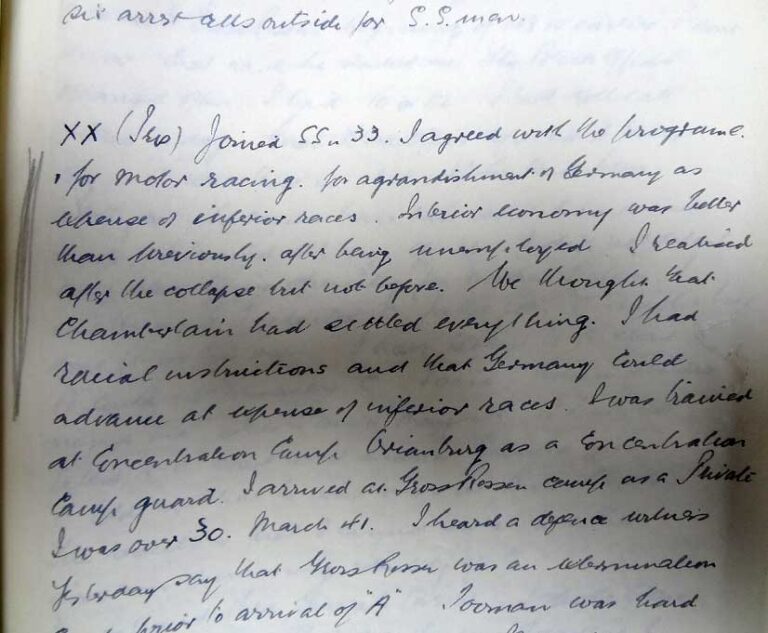

As previously explained, the consensus was that Hassebroek was ‘decent to the prisoners’, but he was, by his own admission ‘a convinced Nazi’. During the trial, Hassebroek tried to depict himself as an ordinary soldier following orders without ever questioning them. ‘As a soldier,’ he said, ‘I did not have to think if concentration camp was correct’ (WO 235/552).

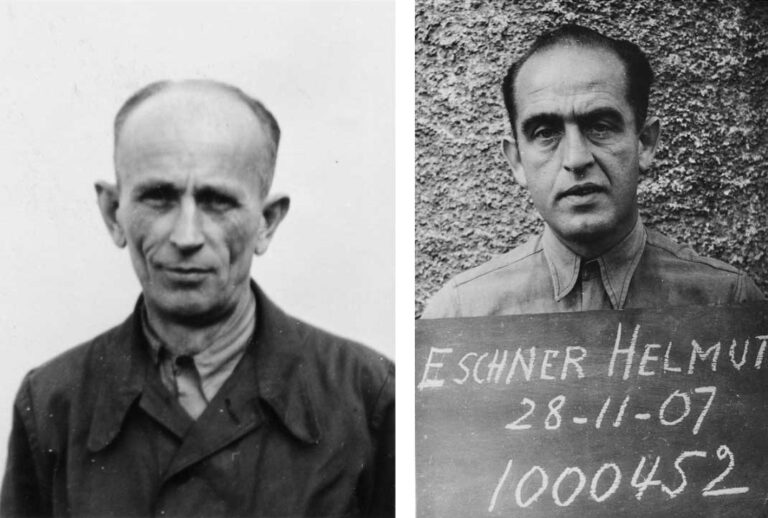

Before the war, Helmut Eschner had mostly worked in shoe factories. He joined the SS in 1933, and the Nazi party in 1937. Called up in the Waffen SS in 1940, he was sent to Gross-Rosen as a guard in 1941. He then became a clerk and, eventually a Rapportführer, mainly in charge of the gruelling roll call.

Like Hassebroek, Eschner was a proud SS. ‘I agreed with the programme for (…) agrandishment of Germany at expense of inferior races’, he stated, before adding ‘We thought that Chamberlain had settled everything’ (WO 235/552).

Eschner, known in the camp as ‘der schöne Helmut’ (the beautiful Helmut), was also a very violent man. Eryk Jozef Piszcek, a Polish political prisoner at Gross-Rosen from the end of 1943 to February 1945, stated Eschner had ‘knocked out all [his] upper teeth’ and that he liked getting drunk and, alongside others, whipping prisoners to death.

Arrested by the Americans in 1948, he initially denied having ever been at Gross-Rosen. ‘On my original arrest,’ he explained, ‘I had seen an SS Captain badly wounded and he advised me not to admit being in a concentration camp staff as I would be beaten up – the same as he had been’.

Lithuanian SS-Rottenführer Eduardas Drazdauskas denied having been at Gross-Rosen, despite having been formally identified by former prisoners. He stated:

‘I am not the same person as referred to by all the witnesses as the Block Officer of Gross Rosen Camp. My name is a well-known Lithuanian name. I have a brother and a cousin’.

Catalogue ref: WO 235/552

Having been beaten by Drazdauskas, Tadeuz Czechowski declared: ‘it is impossible to make a mistake’.

Described as ‘the most feared officer in the camp’, and ‘a sadist’, he was in the habit of beating prisoners for fun. ‘[Drazdauskas] killed many people,’ Polish author and journalist Mieczyslaw Rotanski stated, ‘he tortured them, killed them and broke their ribs (…). He was a sadist, weak criminal’ (WO 235/552).

At no point did any of these three men express regrets, nor shame for their role. They were all sentenced to death on 22 October 1948.

However, sentences were not confirmed. Hasselbroek’s was commuted to life imprisonment, and eventually reduced to 15 years in 1950. He was released in 1954. Both Eschner and Drazdauskas were released. Even though they ‘were proved by the evidence (…) to be the brutal types such as apparently made a good junior N.C.O. in the SS’, the Deputy Judge Advocate General, Russell of Liverpool, concluded that they were ‘two ordinary SS Corporals’ and would not have understood the illegality of the execution of Allied prisoners of war (WO 235/553).

Helmut Eschner was eventually given a 12-year sentence by a German court in 1952.

‘A camp within a camp’

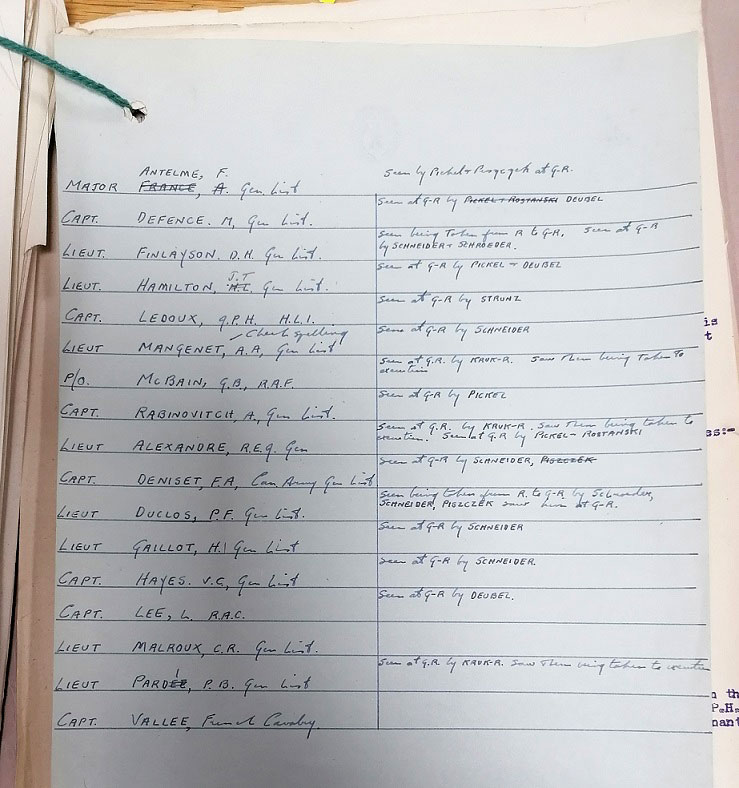

There was a special barrack in Gross-Rosen, known as ‘Weather Station’. Surrounded by barbed wire and described by witnesses as ‘a camp within a camp’, Weather Station was housing ‘Special prisoners’ doing ‘secret work’. Prisoners who wore civilian clothes with no badge and no number (but sometimes a W painted in red on the back). Prisoners whose head was not shaved and to whom talking might mean being shot on the spot. Prisoners who were not registered in the camp books. Prisoners rumoured to be some of the 18 missing British agents from Section F, the French section of SOE.

Hassebroek, Eschner and Drazdauskas were all adamant no British officer had ever been in the camp. Witnesses, however, firmly place a group of at least 10 men in Weather Station in July 1944, where they were ‘severely ill-treated’ by Drazdauskas.

‘Those prisoners at 04.30 on a Sunday morning were taken to block 22. They were undressed, taken (…) to crematorium and (…) shot dead’.

Some witnesses ‘came to the conclusion that they were liquidated’, but others reported: If I had heard anything about the shooting I would have been cremated’ (WO 235/552).

It is assumed that the agents, arrested in March 1944 and first interrogated in Paris, were ‘evacuated’ to the infamous Rawitsch prison before being transferred to Gross-Rosen by special transport July 1944. Kriminal Director Kopkow, of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA, the Reich Security Main Office), claimed that ‘he saw the signature of Himmler on the shooting order’ (WO 309/1295).

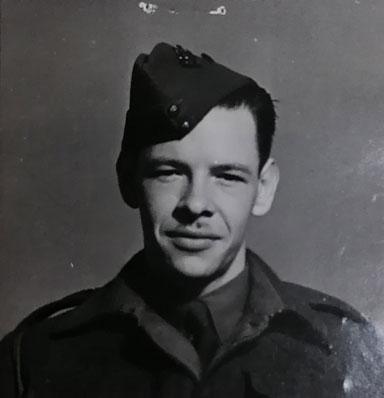

And so Gross-Rosen was the final destination of two young men, Captain Marcel Defence and Captain Adolphe Rabinovitch, and their fellow F-section agents.

Born in 1920, Marcel Defence was first parachuted in France in 1943 to work as a wireless operator. Dropped in France for a second mission on 7 March 1944, he was almost immediately picked up by the Gestapo.

‘Unreliable in his judgement but brave and full of dash’ according to his instructors, he spoke ‘English with a strong French accent and French very badly indeed’.

Maintaining constant communication with London, ‘Defence showed great courage during his two missions in France’ and was awarded a mention in despatches (WO 373/100/427).

Adolphe Rabinovitch, born in 1918, had studied zoology at the Sorbonne and entomology at the University of California, before returning to France to enlist in 1939.

One of his instructors noted: ‘he is very pedantic and talks slowly, but continuously, which rouses the worst in one’. His ‘total lack of a sense of humour’ didn’t prevent him from becoming ‘one of the most efficient and reliable w/t operator in France’, sending nearly 200 messages from the field (HS 9/1223/4). Having ‘showed great courage and disregard for his own personal safety’, Rabinovitch was awarded an MBE (WO 373/104/95) and a French Croix de Guerre (WO 373/185/1085).

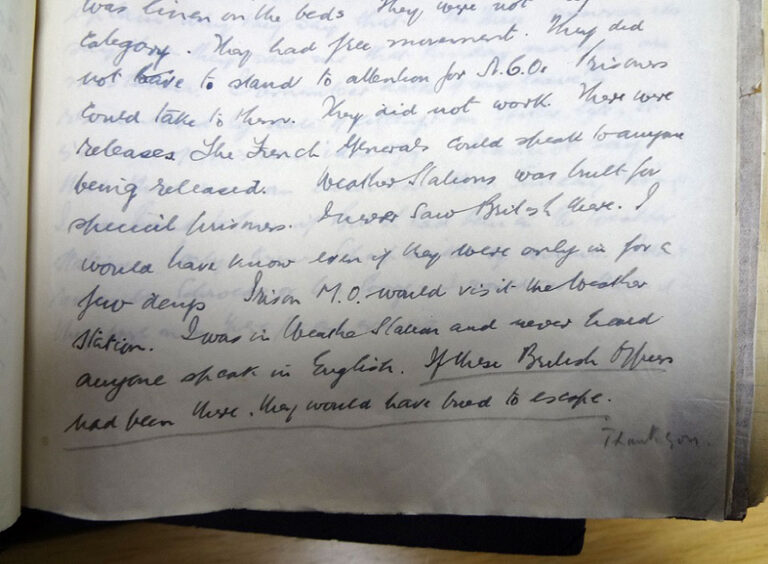

During the trial, Eschner stated: ‘If these British officers had been there, they would have tried to escape’. Someone in the Judge Advocate General’s Office commented: ‘Thank you’ (WO 235/552).

However, Mieczyslaw Rotanski had also heard Escher say: ‘the only way out is by the chimney’.

Major Leniewski and his investigation team, noting it was ‘a very difficult case’, had very little doubt as to the fate of Defence, Rabinovitch and the other agents.

As a team was sent to investigate in 1948, Captain A Nicolson, of the War Crimes Group, wrote:

‘It should be noted at the outset that very little is known about Gross-Rosen, practically nothing about Rawitsch, and there are very few traces of the staff of the Stapo HQ Breslau’.

Catalogue ref: WO 309/350

We now know considerably more about Gross-Rosen, but it’s perhaps worth noting that the camp was only surrounded by electrified barbed wire (as opposed to high walls), and that civilians worked alongside the prisoners in the workshops of Siemens, Daimler-Benz or Krupp. ‘Ordinary people’ would have been aware of what was going on.

And this brings me back to how difficult I found it to stick to the ‘ordinary people’ theme. The ‘ordinary people’ sustaining the concentration camp system, the commandants, the guards, the block leaders, ceased to be ordinary the moment they chose to disregard humanity. The ‘ordinary people’ trapped in the system because of their faith or politics, their sexual orientation of their ethnicity, ceased to be ordinary the moment they had to fight for survival.

It is difficult to know how many prisoners were in Gross-Rosen. It is estimated that at least 120,000 people, including over 25,000 women, passed through the camp, and that at least 40,000 lost their lives. As ever, today I am grateful for the courage, sacrifice, and resilience of so many extraordinary people.

Thanks for this completely fascinating account of a place that I had no idea existed. The records and personal accounts together provide a stark and heart breaking picture of the dark events and crimes that occurred there, seemingly for the most part unpunished. Another ghastly chapter in the Nazi story…

As a person who was born in London in 1949 it is so very hard to believe the atrocities that went on in Nazi German during WW2.

I find it so hard to imagine the suffering endured by the concentration camp prisoners.

How can fellow human beings be so cruel and sadistic?

Even after researching this history since my retirement it is impossible to believe,even though the facts prove it true.

How can people disbelieve and deny that these acts didn’t happen???

God bless all these poor people.

When I was researching my book on SS-Major Horst Kopkow (available on amazon under that title and name) I visited Gedenkstätte Gross Rosen in Poland. Their archive today is very small and most of it comes from files held at Kew. Including the map from WO 235/552. Unfortunately the researcher they sent over only copied the WO 235 files, not the ones in WO 309.

The reason why Gedenkstätte Gross Rosen and Ravensbrück have no wartime camp records is that a destruction order arrived and all the records were burned in the camp crematoria.

SS-Major Horst Kopkow was responsible for all the captured Allied agents (from the east and west) and have the orders for their execution in 1944. Kopkow later came an agent/consultant of MI 6.

My reader’s ticket has expired, the first time in 30 years. I will be getting a new one.

My Mother was a slave laborer at Ober-Altstadat, one of the sub-camps of Gross-Rosen

(Never forget…requiem im pacem)

I found the information about Gross Rosen very interesting. However I must correct the researcher

vis a vis the photograph shown of Captain Alec (Adolphe) Rabinovitch. The photograph is not

of Alec Rabinovich. I have researched his life and history with the SOE F section. I have in my research documents several photographs of Capt. Rabinovitch in my possession. I do not know the young man

pictured here, but it is certainly not Alec Rabinovitch..

Yours Sincerely,

Rosy Frier-Dryden

An interesting article. Thanks

Lt Alexandre – one of the SOE officers murdered at Gross Rosnen – actually lived at 55 Selwyn Avenue in Kew,

Before the War Roland Eugene Alexandre was a young aircraft fitter at the airfield in Feltham. Born in 1921 he had grown up in France, but had come to England as a teenager when his mother had returned after the death of Roland’s father.

Just after his 22nd birthday in August 1943 Roland joined SOE. His personal report said that he was ‘A good, competent, cheerful little man, full of zeal and with a good head. Would make a most competent organiser. A valuable life.’ He was also bilingual – a valuable skill. However, his trainers found that he was ‘a little immature with an excessive interest in the opposite sex.’

By this time, he was living in Kew with his fiancé Joan Sutton, a laboratory assistant.

On the evening of 8 February 1944, Roland was finally parachuted into France. He was to lead a local resistance group in destroying German locomotives in an engine shed at Poitiers. Unfortunately, he immediately fell into the hands of the Germans, as the group was controlled by the Gestapo.

Thereafter little is known of his fate. An eyewitness reported he and several other agents had been interrogated in Paris and had ‘travelled for four days to Germany and then taken to Ravitsch [a village on the Polish/Czech border], here they were badly treated in solitary confinement and hand cuffed at night.’ There’s note on his file that he was ‘believed killed at Grossrosen.’

Joan Sutton was only provided with brief details months after his death, after the war she wrote to the War Office. She concluded her letter: ‘I have been very patient but really cannot stand this uncertainty any longer.’ In all honesty SOE only knew that he had been seized by the Germans from a wireless message.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission gives Alexandre’s date of death as being 19 May 1944: the date he was last seen alive. He is commemorated on a memorial in Brookwood Cemetery, near Woking, which mark the deaths of nearly 3,500 men and women the circumstances of whose deaths being such that they could not appropriately be commemorated on any of the campaign memorials in the various theatres of war.

My grandfather was a German immigration to this country

Some time before 1900

He came here in order to work. He was a baker.by trade

He met and married my grandmother in Bradford

She was the. Daughter of a coachmaker of some standing

They moved to Manchester and had 8 children My mother being the youngest

At the start of world war one there was rioting in the streets

And bricks et were thrown through the Windows of there house. Many.of the neighbours had been given bread and cakes Tec It was a working class area of Manchester.

My.grandfather was taken.by the police and eventually confined to a p.o.w.camp

My grandmother was fined for not reporting she was married to a German. 25 shillings was.a lot of money in those days

She died in 1917 leaving her children orphaned

The family were very close and I am.proud to have had them

In My !I’ve

All this was kept secret and did not come to life until.My aunt died and some very old letters were discovered in an old attache case at the back of a wardrobe

There is so much more I discovered in my 30year old search and I will not bore you

Just to tel! You a little of my grandfather I am proud to have some connection to a brave and loving family

Thank you so much for this article. I just write a book about KL Gross Rosen SS doctor and Eschner seems to be everywhere in a prisoners camp hospital. What a scoundrel. It is very important to commemorate this forgotten concentration camp.

Dear Dr Desplat,

As another person commented above, the image above of Adolphe Rabinovitch. Catalogue ref: WO 235/552 is incorrect. I know who this person is (my great uncle) and I know his history involved Gross Rosen, but can you change the image please as I don’t want my great uncle to be forgotten as someone else. I am happy to share other correct information we do have.

Thank you for getting in contact with us. We have now removed the image from this blog. The information that the person in the photo was Adolphe Rabinovitch came from the relevant file (Catalogue reference: WO 235/552).

My mother was one of a Dutch group by the name of Philips Phace Arbieters .As far as I know they arrived to one of the Gros Rossen camps by the name Riechenbach arround 15.6.1944 They came from Auschwitz . They were marched out of the camp in 18/2/1945.

Do you have more infromation about this group?

Dear Nechama,

Thank you for your comment.

To ask questions relating to research, please use our live chat or online form.

I found this a very interesting article on the history of Gross Rosen. Having lived in Jelenia Gora, Dolna Slask which is not too far from the camp, I have visited there a few times and this article has filled some of the gaps in my understanding of the dreadful happenings that took place there in a very dark period of recent history.

Re numbers of SOE agents killed at Gross Rosen, there is a plaque there honoring 19 SOE agents from F section. Two F section names were omitted: Maurice Lepage and Edmund Lesout. So, the total of SOE F section agents killed there is 21. There may well be other SOE agents from the RF and Polish sections who were also killed at the camp….?