On the evening of 30 November 1936, a fire was discovered within the Crystal Palace, an enormous plate glass and cast-iron building located in the Sydenham area of south London. Multiple fire brigades attended, but the fire grew until it could be seen for miles around. Crowds flocked to the scene, which the Guardian described the next morning as ‘like a cup final day’ (see footnote 1). There was shock and awe as local people came to terms with the utter destruction of this iconic landmark.

‘A pleasure house of glass’

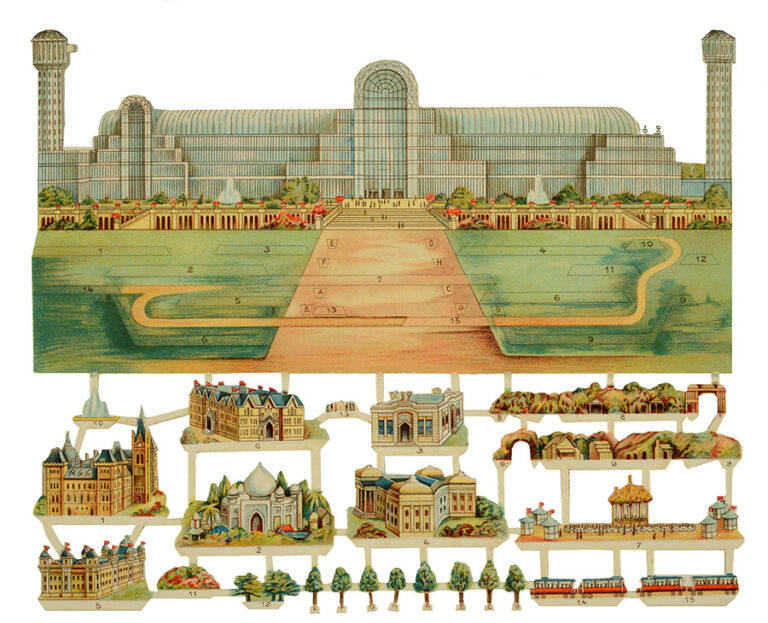

The Crystal Palace was famous for being the home of the 1851 Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, visited by over six million people. After the exhibition ended, the Palace was taken apart and reconstructed on Sydenham Hill in South London, opening in 1854. Over the next eight decades, the Crystal Palace experienced a new life attracting crowds to exhibitions, festivals and concerts. Its newly designed gardens were also popular and hosted regular fireworks displays hosted by Brock’s Fireworks. The Palace’s iconic name began to be used for the area in which it stood.

In 1911, the Palace hosted the Festival of Empire Exhibition, the largest single event ever held at the Palace. The exhibition was an attempt to strengthen the British Empire and encourage emigration, by displaying exhibits focused on different colonies and dominions around the world. While the event was generally well-received at the time, it marked the beginning of a period of financial decline for the Palace.

Fire and farewell

Fires had broken out in the Crystal Palace before, notably in 1866 and 1923, when parts of the building were severely damaged (footnote 2). However, the fire of 1936 was something different, burning quickly and completely destroying the central transept.

The morning after the fire, the Guardian published the following report under the title ‘London flocks to the Palace pyre’:

‘There was no mistaking the earnestness of London’s farewell to the Crystal Palace tonight. The news was given out in one of the earlier news bulletins on the wireless, but long before that the flickering orange glow into the sky, which could be seen from Islington, Willesden, and even farther north and as far south as Hayward’s Heath, had begun to draw the crowds in hundreds of thousands, by bus and car and train.

Men and women and children tripped and stumbled over the miles of wriggling hose-pipes, slopped about in the muddy streets, and pressed forward closer to the roaring blaze transcending even the most spectacular of Mr. Brock’s famous benefits.’

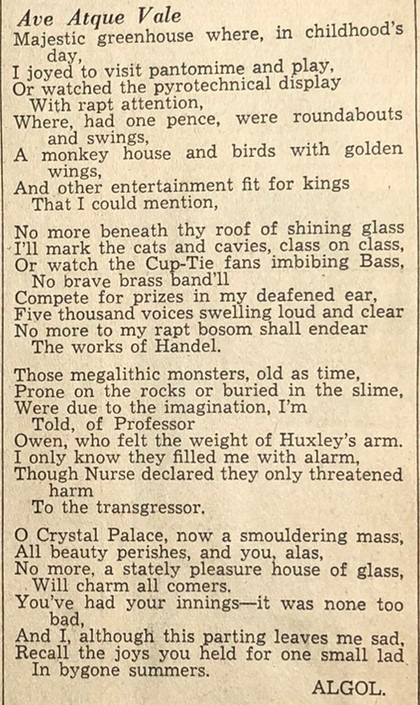

A poem titled ‘Ave atque vale’ (‘Hail and farewell’) penned by ‘Algol’ was published in The Morning Post to mourn the loss of the Palace. Its final stanza reads:

O Crystal Palace, now a smouldering mass,

All beauty perishes, and you, alas,

No more, a stately pleasure house of glass,

Will charm all comers,

You’ve had your innings-it was none too bad,

And I, although this parting leaves me sad,

Recall the joys you held for one small lad

In bygone summers.

Aftermath and legacy

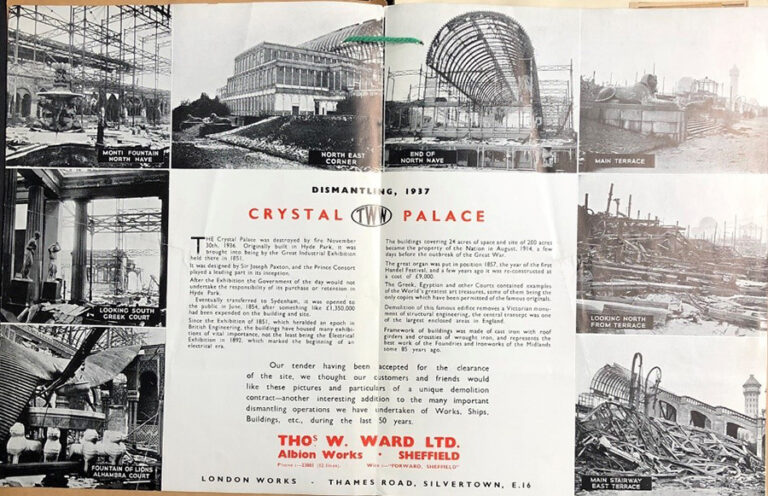

In files held at The National Archives, there are documents relating to the fire and its aftermath. One contains a booklet called ‘Dismantling Crystal Palace’ produced by site clearance company Thomas W Ward Ltd, a company employed to clear the site. It contains shocking photographs of the extent of the damage and information about the building and its fate. The booklet states ‘Demolition of this famous edifice removes a Victorian monument of structural engineering, the central transept was one of the largest enclosed areas in England.’

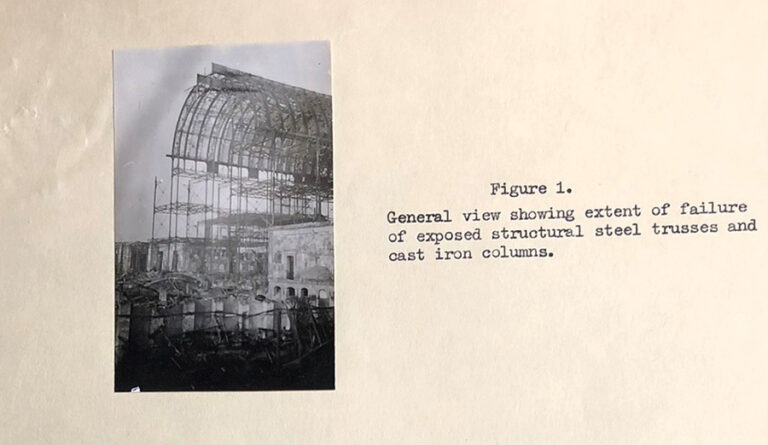

On 23 December 1936 an inspection was carried out by Messrs. Cowley and Davies and they reported:

‘Confirmation of the extreme vulnerability of unprotected structural steel. As far as could be seen failure took place generally by the breaking of the cast iron supporting columns as a result of the bending stresses induced in them by the deflection of the girders… the transformation of the gravel aggregate to a pink and white colour and the presence of molten glass suggested that considerable temperatures had been attained in the vicinity.’

Visiting Crystal Palace Park today, you can still see remnants of the old building in the shape of the land and the statues and stonework that still exist. The gardens, including the famous dinosaur sculptures originally unveiled in 1854, are also still a focus for visitors. A museum located near the site also tells the story of the palace, its history and its fate.

Footnotes

- ‘London flocks to the Palace pyre’, The Guardian, Manchester, 1 December 1936. Catalogue ref: RAIL 1057/2713

- ‘Dismantling Crystal Palace’, Thomas W Ward Ltd. Catalogue ref: RAIL 1057/2713

And is that shiny black mass which my grandfather found in a South London park, which he described as a thunderbolt molten glass from the Crystal Palace ?

My father John Sanderson born in 1921 aged 15 described seeing it burn down in 1936. His father Major Alex Sanderson (RAE) DSO MC bar was in charge of repairs to the bombed London Underground system in WW2

My great grandfather, apparently an avid arsonist (possibly convicted), has had my family suspicious for a long time having claimed he saw it burning a little primitively describing a singular flame he noticed as he walked by it on his way home.

The poor old Crystal Palace is consigned to memory. Maybe a new one can be built. It would be nice.

I walked through the remains of the palace today. A sunny day people enjoying the open views across to the north downs and beyond. This beautiful open space with air to breathe and free in every way. Not developed, not monitised, not barred from access. Let nature cover the debris of the remains and let some wildlife inhabit. It’s beautiful, let it be… I was born here sixty years ago and live here and walk daily…

My mother has a piece of Crystal Palace handed down to her from generations when it burnt down

beautiful sentiment, thank you for sharing.

Amazing. I can still remember my grandparents, now passed away telling me of witnessing this disaster from their home in Dulwich, their shock and dismay and sadness of course. Stuart X