The campaign for women’s suffrage is often characterised by its militant factions and leaders like Emmeline Pankhurst who used bombs and destruction of property to get their message across. That characterisation is accurate, but it’s not the whole story. In fact, militant suffrage actions didn’t begin with the Women’s Social and Political Union…or with women at all.

With the help of archives, historians and records experts, it is possible to uncover the real story behind what we think we know. This is what The National Archives is aiming to do with the second series of our podcast, On the Record at The National Archives, which is looking at the topic of protest.

In episode one we used the medieval records in our collection to uncover the real story of the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. In episode two we explore how a lesser-known male suffrage movement called Chartism advanced the suffrage agenda, and at how the militant tactics of the women’s suffrage activists fit into a large historical trend.

To coincide with the release of episode two I asked The National Archives’ Chris Day, Head of the Modern Domestic Records Team, and Vicky Iglikowski-Broad, Principal Diverse Histories Records Specialist, a few more questions that we couldn’t fit into the episode.

[Katie]: Chris, you mentioned in the episode that the Chartist movement peters out. Why was that?

[Chris]: In 1848 the dominant part of the Chartist movement were those committed to using ‘moral force’ (ie non-violent political protest) to achieve their aims, led by people like Fergus O’Connor. In 1848 around 150,000 people assembled for a demonstration on Kennington Common, South London. O’Connor and others then presented a Chartist petition to Parliament signed by six million people (Parliament claimed there were only 1.9 million valid signatures). The petition and the demonstration failed and the moral force campaign lost its momentum.

Illustrated London News image of a Chartist convention, 15 April 1848. Catalogue ref: ZPER 34/12

In its place there was, in 1848, an increase in more radical action by ‘physical force’ Chartists, with figures such as William Cuffay planning insurrection. Many of these actions failed to secure their aims, and Cuffay and many others were arrested for sedition and other crimes and transported to Australia.

After this, Chartist activism declined. However, middle-class radicals continued to call in Parliament for reforms similar to those called for in the People’s Charter, with some success later in the 19th century.

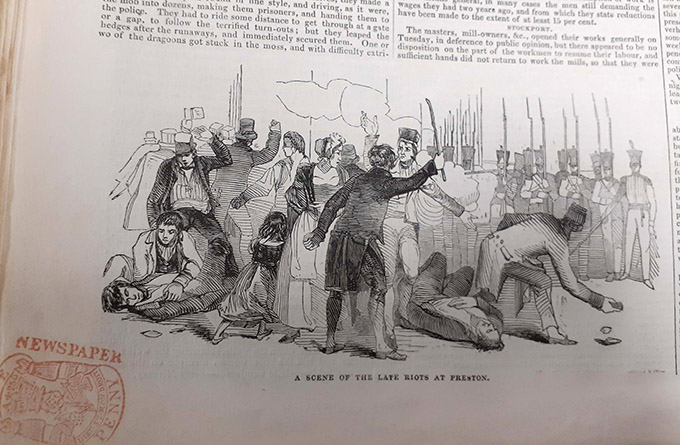

Illustrated London News image of rioting Chartists in Preston, 27 August 1842. Catalogue ref: ZPER 34/1

[Katie]: Do campaigners for women’s suffrage reference the Chartists within their campaign as a model of success, or in any other way?

[Vicky]: Women’s suffrage campaigners relied on traditional methods of political organising, and many of these methods reflected those of the Chartists. Different branches of the women’s suffrage movement were linked to labour movements of the time to different extents; some were very proud to hark back to the traditions of the Chartists, while others were determined to create a new kind of politics and new kinds of protests.

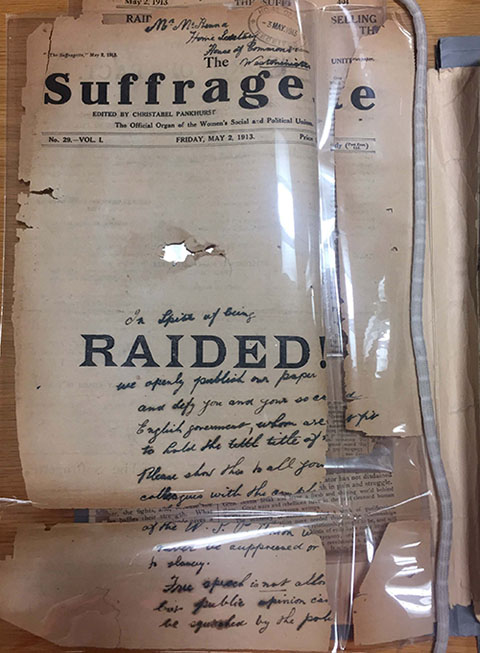

Copy of ‘The Suffragette’ found wrapped around a bomb at St Paul’s Cathedral, May 1913. Catalogue ref: HO 45/10700/236973

[Katie]: Vicky, we end the episode in 1918 with the enfranchisement of working class men and the partial franchise of women. Did the campaigning continue until women got the vote on equal terms to men, and, if so, did the form of protest change or evolve?

[Vicky]: It is really interesting to note the change in campaigns from 1918 onwards. The campaigns for the franchise on equal terms absolutely continued, but in a very distinct way from the pre-First World War campaigns. Indeed, some of the major women’s suffrage societies disbanded or changed their focus, such as Emmeline Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union.

The 1920s saw a spate of new women’s organisations formed, such as the Open Door Council and the Six Point Group. Women’s groups continued deputations to see government officials, but the most noticeable thing was the move away from militant actions – maybe it seemed less appropriate in such a recent post-war society? As well as the franchise women were campaigning on much wider issues, around equal employment rights, rights for widows and equal pay (this had always been the case, but getting the vote tended to dominate pre-war campaigns).

Furthermore women could be MPs and some women at least could vote, so women increasingly influenced politics in ways they previously couldn’t – through the formal parliamentary process, which is what they had always wanted.

If you are interested in finding out more about the two campaigns for suffrage there are plenty of other blogs about the Chartist and women’s suffrage movements which use our original documents.

On the Record at The National Archives: series two

Episodes one and two are now available on the Archives Media Player and on podcast listening apps. The third and final instalment for this series will be available from 30 January and will focus on stories of black people in 1960s and 70s Britain using the legal system to fight racism and discrimination.

You can also catch up on series one which focused on espionage using personnel files, secret government reports, and declassified correspondence to uncover the true stories of famous spies.

Subscribe: iTunes | Spotify | RadioPublic | Google Podcasts